Pueblo pottery facts for kids

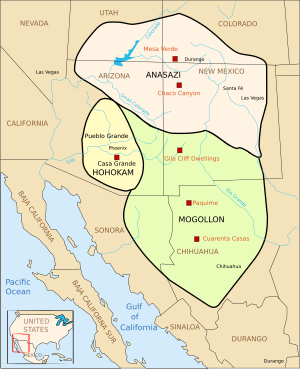

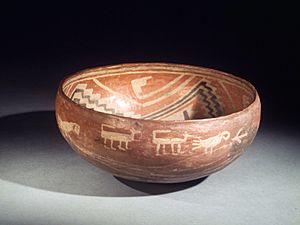

Pueblo pottery refers to amazing clay objects made by the Pueblo people. These include their ancestors, the Ancestral Puebloans and Mogollon cultures. They lived in the Southwestern United States and Northern Mexico.

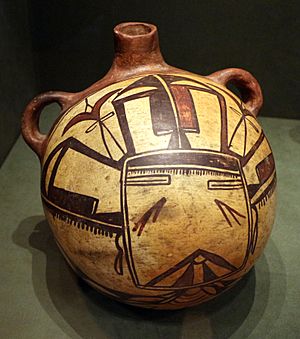

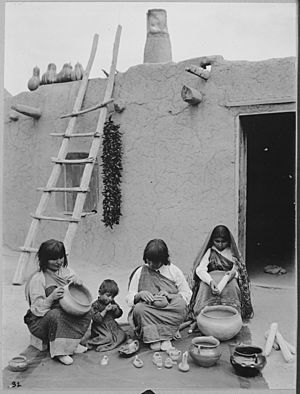

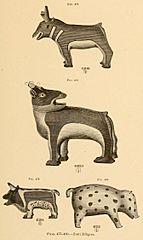

For hundreds of years, pottery has been super important to Pueblo life. It was used for daily tasks and special ceremonies. The clay comes from local areas. Most pots are shaped by hand, not on a spinning wheel. They are traditionally fired in a special pit dug in the ground. These items include jars for storage, water bottles, serving bowls, and ladles. They helped with everyday needs. Some plain pots had simple patterns made with fingers or sticks. But many were painted with cool abstract designs or pictures. Some pueblos even made pots shaped like animals or people, called effigy vessels. Today, Pueblo pottery is also made as an art form to sell. This is similar to how pottery was traded long ago.

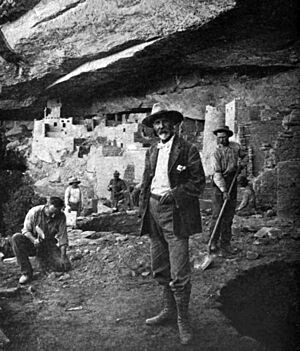

In the 1880s, the railroad brought new people to Pueblo lands. These included scientists who study cultures, called ethnographers, and tourists. Sadly, this led to many thousands of pottery pieces being taken to museums and collectors. Some were taken without permission. This also started the problem of stealing artifacts from old sites. Around 1900, new art styles began to appear. A Hopi-Tewa potter named Nampeyo of Hano was a leader in this. A few years later, María Martinez from San Ildefonso Pueblo also became famous. In the 20th century, Pueblo pottery became a big part of the art market. Dealers helped artists sell their work to museums and collectors. This made the value of modern pottery go up. It also created a black market for older, stolen pieces. This led to stronger laws to protect ancient sites and Native American items. These laws include the Antiquities Act of 1906 and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990.

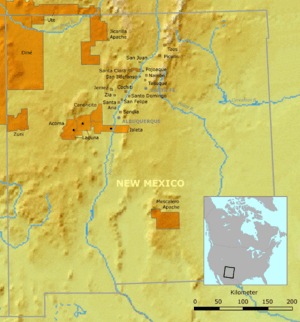

Today, Pueblo potters often follow their family's traditions. But some also create unique styles that are new and exciting. They still respect their ancestors' ways. Many artists say their grandmothers taught them. There are 21 federally recognized pueblos in the Southwest today. Each has its own special pottery styles. Nineteen pueblos are in New Mexico, one in Arizona, and one in Texas. Many Pueblo people speak their native languages, plus English and Spanish. They have worked hard to keep their cultures, languages, and beliefs strong. For example, the Tewa people of Kha'po Owingeh (Santa Clara Pueblo) and P'ohwhóge Owingeh (San Ildefonso Pueblo) are known for their black pottery. The Keresan-speaking people of Acoma Pueblo and the Shiwiʼma speaking people of the Pueblo of Zuni use many colors and designs.

Contents

How Pueblo Pottery is Made

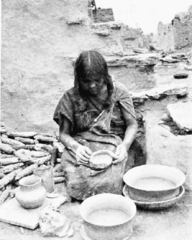

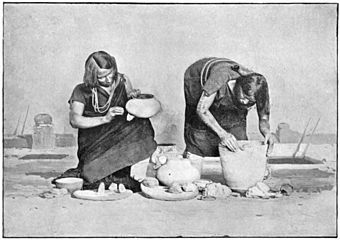

Traditional Pueblo pottery is made by hand from clay dug from the earth. The clay is carefully cleaned. Potters use coiling techniques to shape the clay into useful items. These include pots, storage containers for food and water, bowls, and platters. Smaller pieces like animal or human figures are often made using slab and pinch pot methods.

To make the clay stronger, potters add special materials. These are called tempering agents. They can be sand, crushed pieces of old pottery, or volcanic ash. Pots are often decorated with carved patterns or polished until they shine. They can also be painted with natural mineral paints or colored clay slips. These designs become permanent when the pot is fired. The pots are hardened into earthenware in a fire pit dug into the ground. Local materials like wood, animal dung, or coal are used as fuel.

-

María and Julián Martinez firing black pottery in a pit, around 1920.

-

Sara Fina Tafoya firing black pottery at Santa Clara Pueblo, around 1900.

-

A Hopi woman from Oraibi making coiled pottery.

A Look at Pueblo Pottery History

Pottery has been found in areas where the Ancestral Puebloans lived. Some pieces date back as far as 200 AD. Much of this ancient pottery in New Mexico was made by people who are likely related to today's Pueblo people.

Fired pottery techniques probably arrived in the Southwest from two main directions. One route came along the west coast of Mexico, moving into what is now Arizona. The other was an inland route, following the Sierra Madre mountains into New Mexico. Pottery skills spread northward, roughly along the New Mexico-Arizona border. They continued into Colorado, Utah, and the Grand Canyon area. Another route might have come from Mexico, following the Rio Grande north through El Paso into New Mexico.

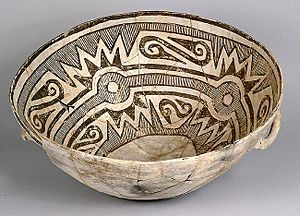

The Mimbres people, part of the Mimbres branch of the Mogollon culture, were masters of pottery between 1000 and 1130 AD. Many of their designs are still used in Pueblo pottery today. Modern Pueblo people believe they are descendants of the Mogollon. The oral histories of the Acoma, Hopi, and Zuni peoples also link them to the Mimbres and Mogollon.

Ancient Pueblo pottery can be put into two main groups. One is rough, textured pottery for everyday use like cooking and storing food. The other is more finished and often painted pottery for serving food and carrying water.

When Spain colonized the Southwest, it changed the lives of Pueblo potters. Especially those living in the Rio Grande Valley. They started making items for the Spanish, like candlesticks and chalices for churches. During the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the Pueblo people drove the Spanish away. At this time, two main pottery styles existed. One was made by the Keres pueblos, and the other by the more isolated Zuni. Both used "watery" mineral glazes with black or brown designs. The Tewa potters used a cream-colored slip and painted designs in black glaze. This made their pottery look very fine and precise.

After the Spanish returned in 1692, most pueblos stopped making glazed pottery. Instead, they made pottery with a matte finish. They used plant and mineral paints applied before firing. For twelve years (1680-1692), the Pueblo people were free from European influence.

Another big change happened with the arrival of the railroad in New Mexico in 1880. This brought travelers, scientists, and tourists. It also led to collecting expeditions, buying and selling, and stealing of old pottery.

Pueblo pottery has been grouped into historical periods. This system is called the Pecos Classification. It was created by anthropologist Alfred V. Kidder in the 1920s.

Pueblo I Period (750–900 AD)

Pottery from the Pueblo I Period followed the Basketmaker Culture. Simple gray pots with neckbands were common. Redware and black-on-white pottery also appeared. Gray utility pottery was found across the Mogollon, Hokoma, and Ancestral Puebloan lands. Potters experimented with sand or crushed sandstone to harden their clay. Later, potters in the Chaco Canyon area used crushed potsherds to temper their clay. Around 750 AD, a red pottery type emerged. It had red iron oxide paint applied after firing, but the color often flaked off.

Pueblo II Period (900–1150 AD)

Pueblo Period II pottery was mostly corrugated gray utility ware and black-on-white ware. Some black-on-orange trade pottery was also found. During this time, people started living in larger communities with shared public spaces like plazas. Many types of items were made, including ladles, pitchers, and water canteens. Some of this pottery was used for trading. Red Mesa black-on-white pottery was made in large amounts across a wide area. This included Chaco Canyon and areas west to Holbrook, Arizona, and east to the Rio Grande Valley. Red Mesa bowls had bright white insides with fine black zig-zag lines. Jars were painted on the outside.

Pueblo III Period (1150–1350 AD)

Pueblo III Era pottery was mainly corrugated plain grayware and black-on-white ware with geometric designs. A key feature of this era was the rise of colorful polychrome pots later on. These had black, red, and orange designs on a white background. The use of mineral pigments like copper, iron, and manganese began around 1050–1200 AD. This happened as far north as the San Juan Basin and south to Zuni.

Pueblo IV Period (1350–1600 AD)

During the Pueblo IV period, the corrugated utility pottery slowly disappeared. Instead, highly decorated polychrome styles and red, yellow, and orange pottery became popular. Mineral paints (not plant-based) and glazes appeared. Some pots had Kachina designs and symbols. Rio Grande Glaze Ware was made from Santa Fe in the north to Elephant Butte in the south. Glazing was common, with pots fired at high temperatures before being painted with lead-based pigments. This stopped when the Spanish cut off the supply of lead.

Many pieces of Pueblo IV pottery have been found at Pottery Mound. This was a village along the Rio Puerco, lived in from 1350 to 1500 AD. Pottery Mound polychrome ware often had different colors on the inside and outside. It was decorated with various mineral paints before firing. Pottery found here was made locally and also imported from places like Hopi, Acoma, and Zuni.

Pueblo V Period (1600–Present)

During the Pueblo V period, Pueblo culture was changed by Spanish colonialism. The number of people in pueblos decreased due to European diseases. This also affected their traditional ways of life. Later, the U.S. government created reservations. This caused some people to leave their homes and move to other pueblos.

Some archaeologists believe Pueblo potters started firing their pots using cattle and sheep dung during this time. The Spanish kept cattle, creating a lot of dung. Using dung saved wood, which could be used for building. This led potters at Santa Clara and San Ildefonso pueblos to try new firing methods. These methods created the famous blackware pottery. Lead-based glazes disappeared for 150 years because the Spanish controlled the lead supply. Without glaze pigments, some Rio Grande pueblos stopped painting pottery. Others switched to using plant-based paints.

Examples of Pottery from Different Periods

-

Pueblo I Period greyware jar from Chaco.

-

Pueblo V Period Maria Martinez black-on-black pot, 1945, at the DeYoung Museum.

Main Pottery Styles

Polished Blackware

After 600 CE, a type of shiny black pottery was made in south-central New Mexico. It was made from brown clay but had very polished, shimmery black insides. This pottery was made until about 1400 AD. Scientists found that the black color came from "reduction-firing." This means reducing the oxygen during firing. This changed the hematite in the clay into black magnetite. The same method was used by Tewa potters at San Ildefonso Pueblo and Santa Clara Pueblo in modern times.

Greyware (Ancestral Puebloan Utility Ware)

Greyware, or utility ware, is the oldest pottery style in the northern Southwest. It is gray and has a rough surface. It was used for storing and cooking food. Pots are the most common forms found. But bowls, water canteens, smoking pipes, and ladles have also been found. Potters might have discovered reduction firing, as many pots are dark gray or black. This was not from cooking soot. Many potters added sand or ground sandstone to their clay to make it harder.

Plain Grey Utility Ware

Plain grey ware is sometimes called "undecorated white ware." It is found in the Petrified Forest area of Arizona, the Zuni area, and the Cebolleta Mesa area of western New Mexico. It is also found in the Rio Grande areas and north towards the Colorado Plateau.

Corrugated Ware

Corrugated grey pottery for everyday use ranges from light to dark grey. Many pots show traces of soot, meaning they were used for cooking over a fire. This pottery was made by coiling the clay. Then, the coils were pressed together with a stick or fingernail. Sometimes the patterns formed a design. But these pots were not scraped, polished, or painted.

Plant-Based Painted Ware

Ancestral Puebloans in western areas like northern Arizona developed paints from plants to decorate their pottery. Some potters at Mesa Verde and in the Upper San Juan regions of Colorado also used plant pigments. Plants like beeweed and tansy mustard were used.

In southeastern Arizona, Roosevelt Red Ware was developed. It used plant-based pigments instead of minerals. It was first made by the Kayenta people around 1280 AD. Very large bowls, dated to around 1350 AD, are thought to have been used for feasts. They are not found in burial sites, which supports this idea. These bowls often had a line painted inside, perhaps a "maximum fill line." Roosevelt red ware was traded with other people in the Southwest.

Mineral Painted Ware

The Ancestral Puebloans created a type of black-on-white pottery. It was made widely across New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona. There were many types, including La Plata, White Mound, Lino, Kiatuthlanna, Chaco, Mesa Verde, and Red Mesa. Designs included parallel lines, triangles, and zig-zags. Ground hematite was used for black paint. Reddish-black and maroon paints were made from ground iron oxide and rocks with manganese.

Red Ware

A mineral-based, slip-glazed Red ware was developed early. It involved putting a red clay slip on the pot. The slip came from minerals like iron, copper, and manganese. For open bowls, sometimes only the inside or outside was slipped. The slip was sometimes polished before firing. This pottery was widely traded. Often, another color was added to make black-on-red ware. This became very popular in the Rio Grande regions. Showlow Smudged ware bowls had polished red outsides and smudged, polished black insides.

Jeddito Yellow Ware

Jeddito yellow ware is a special pottery type from the Hopi Pueblo in Northern Arizona. It was traded with the Navajo and New Mexico Pueblo people. Its unique yellow color comes from local clay with low iron. More importantly, starting around 1300 AD, the Hopi fired their pottery with coal instead of wood or dung. There are large coal deposits near Hopi lands. Firing low-iron clay at high temperatures made very strong, hard pottery, almost like porcelain. The clay was not mixed with additives. Surfaces were polished before firing, but not glazed. Pots were often painted with different mineral pigments to create colorful designs.

Polychrome Ware

Colorful pottery with mineral, plant, and glaze paints has been found dating back to at least 1300 AD. Showlow Black-on-red ware, found in Arizona, dates to before 1200 AD. This pottery was covered with red slip and painted with a dark black paint. Many of these pots were traded among Pueblo people.

Glaze-Paint Ware

Glaze paint appeared in southwestern Colorado as early as 500–750 AD. Potters in the Durango, Colorado area might have accidentally created a blue-black or maroon glaze from a mineral with lead. Potters in the Chaco-Puerco, Mesa Verde, and Cibola regions made glazes without lead.

Protecting Pueblo Pottery

The demand for ancient Pueblo pottery led to many important sites being disturbed. This was done to sell items to museums and private collectors. Early archaeological digs, like those by J. Walter Fewkes from the Smithsonian, moved many pottery pieces to museums. This separated the objects from their original homes and communities. Later, in the 1960s, some people used heavy machines like bulldozers to dig for pots. This destroyed many artifacts and ancient sites, including burial grounds. Some books about archaeology even inspired people to steal pots to sell them illegally. Now, there are serious punishments, including jail time, for stealing historical objects from public and some private lands.

Tourists and people looking for artifacts are also responsible for taking items. Some landowners also dig up artifacts on their own property to sell. For example, a Pueblo III Era site in Colorado, called Indian Camp Ranch, sells land plots. Wealthy buyers can build homes and also dig for artifacts on their property. This kind of digging and destruction of history is a loss for scientists and a "spiritual loss" for the descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans.

Some early anthropologists who studied the Zuni, like Frank Hamilton Cushing, James Stevenson, and Matilda Coxe Stevenson, were involved in taking cultural items. Cushing lived with the Zuni for years, adopting their clothes and customs. He was one of the first anthropologists to learn by living with the people he studied. The Stevensons also collected thousands of objects. Between the three of them, about 23,000 Pueblo pottery objects were taken from their tribes between 1879 and 1884.

In 2005, a special police operation in Blanding, Utah, arrested 32 non-Native people. They recovered thousands of artifacts, mostly taken from the Four Corners region. Many were charged with breaking federal laws like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. However, no one was sent to prison. The recovered items included Mogollon, Hohokam, and Anasazi pottery, some as old as 6,000 BCE. Some artifacts were stolen from inside cliff dwellings and were in great condition. These items are now being returned to their tribes. Forest Cuch, a Ute tribal member, said that stealing artifacts "is a dehumanization of native culture by ignorant people. It's essentially very selfish and greedy."

Norman Nelson, a Native New Mexican archaeologist, thinks that 95% of ancient sites have been disturbed. He says that ancient Mimbres black-on-white pottery sells for high prices, especially to collectors in Europe and Asia. In 2009, he estimated that the illegal trade in Native American artifacts was a multi-billion dollar industry each year. He noted that many collectors "don't mind crossing the line" into buying illegally traded objects.

Modern and Contemporary Pueblo Potters

Modern Period (Early 1900s)

Native American pottery has long been seen as a "traditional" art form. But it's the new ideas from individual potters that have helped it grow. Throughout history, unique pieces have appeared that don't fit the usual styles. These were once thought to be mistakes. But they actually show how pottery styles changed over time. For example, a special group of pottery from Laguna Pueblo was made between 1890 and 1920. It used Laguna materials but had Acoma and Zuni designs. This shows how artists experimented and shared ideas between pueblos.

The modern period of Pueblo pottery began around 1900. Before this, the 1800s were a difficult time. Native people lost land, and government schools tried to make them abandon their traditions. Also, archaeologists taking their pottery for museums might have played a role.

In the early 20th century, potters from six Tewa speaking pueblos in New Mexico and one Hopi-Tewa group in Arizona created new designs. They used traditional methods. This started modern and contemporary Native ceramic arts. The need for money and the rise of tourism helped bring Pueblo pottery back to life. While tourism changed some traditions, it also allowed Pueblo people to sell their pottery and other crafts.

Pottery skills are often passed down through families for many generations. Potters teach their children by showing them and telling them. Certain designs become an artist's special style. Families often feel they "own" these designs. For example, the Lewis family from Acoma Pueblo is known for their fine-line designs. These designs have roots in ancient Chacoan culture. They are also known for their "heartline deer" patterns.

The famous Tewa potter María Martinez (1887–1980) and her husband Julían Martinez (1879–1943) from P'ohwhóge Owingeh were very talented. They started going to fairs in the early 1900s, which was unusual then. By 1915, Maria was known as one of the best potters in New Mexico. By 1920, she started signing her pots. She was probably the first Pueblo potter to do this. She was told it would make her pots more valuable. But Maria cared most about the quality of the pots themselves. Another important Tewa potter, Margaret Tafoya (1904–2001) from Kha'po Owingeh, was known for her large blackware pots. She often used designs like a bear paw or the Avanyu water snake.

At Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo), a "San Juan Revival" movement started in the 1930s. Eight women potters, including Regina Albarado de Cata, led this. They studied ancient designs from archaeological sites. Their work often had wide red bands at the top and bottom of the pots, with carved patterns in the middle.

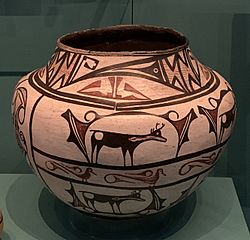

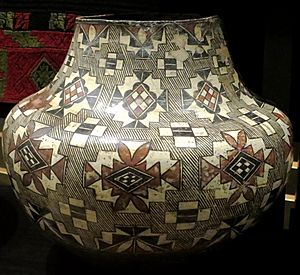

Pottery from the Keresan-speaking pueblos has its own unique feel. Acoma Pueblo pottery was loved for its bright white, thin pots with abstract fine lines and checkerboard patterns. In the modern era, Acoma and Laguna Pueblo refined these lines and added bird designs. Lucy M. Lewis is seen as the most important Acoma potter. She influenced many generations of her family. Artists from Zia Pueblo began to change their traditional bird designs into more realistic birds and flowers. Images of dancers and the Zia sun symbol were also common. Artists from Santo Domingo Pueblo used flower and bird designs with geometric lines, usually in red. Zuni artists started decorating their pottery with dragonflies, deer, owls, frogs, and flower patterns inspired by Spanish influence.

In Northern New Mexico, artists from San Juan Pueblo carve their pottery into beautiful shapes. They are known for their red-on-tan work. Modern artists from Santa Clara Pueblo became famous for their deeply carved blackware. Margaret Tafoya's work was collected by museums and people everywhere. Other Santa Clara artists are known for their clay figures. Artists from Jemez and Cochiti pueblos also make figures and storyteller sculptures. In the mid-1960s, Cochiti artist Helen Cordero's storyteller sculptures became very popular. Cochiti drummer figures and nativity scenes are often sought after more than bowls.

The Hopi in Arizona are also known for figures like clay kachina and animal shapes. But their most famous work is low, wide yellow-ware pots. These were made popular by the early 20th-century artist Nampayo of Hano and her family. Hopi designs often feature swirling, stylized birds and other patterns that follow the pot's shape. Nampeyo was a very important Hopi potter. Her work pushed boundaries and techniques. She was the first Native potter to be recognized nationally and internationally. Her influence spread to other pueblos and artists.

The pueblos of Taos and Picuris, in northern New Mexico, make pottery from micaceous clay. This clay has sparkling surfaces. These pots are often plain, with the shiny mica particles as their natural decoration. The southernmost Pueblo, Ysleta del Sur (Tigua Pueblo), near El Paso, Texas, is not well known for pottery today. However, their potters made useful items like bowls and tortilla irons until the 1930s.

Contemporary Period (1960s–Present)

Starting in the 1960s, many artists, scholars, and museum curators began to show and write about the work of modern Pueblo artists. These artists respected the past but also created new methods and designs. Museums and private collectors started buying these new forms of Native art. By the 1980s, a new market for this art began.

At first, this new work was not widely known. In 1969, a big ceramics show called Objects: USA included only three Native Americans. Another large show, American Craft Today, included only one Native American artist out of 286. However, a 1987 show, The Eloquent Object, had a much higher number of Native artists. Then, in 2003, 2006, and 2012, the Museum of Art and Design held a series of shows called Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation. All the artists in these shows were Native artists.

Many contemporary Pueblo artists want their work to be seen as more than just "traditional" or "anthropological." They want to break free from stereotypes about what Native ceramic art "should" look like. This variety of approaches challenges old ideas about what "modern art" is. It shows the rich and complex nature of Indigenous art in today's world. These artists are "producers of knowledge" who include real-world ideas in their art. Some art collectors and scholars believe older, more traditional Native art is more valuable. They think it's "unadulterated by outside influences." But this way of thinking can limit Native artists. It takes away their voice by focusing only on "tradition."

Comanche art critic Paul Chaat Smith says this can be like an "ideological prison" for Native people. Pottery and Native American art have often been called "craft" or "less advanced" than European art. Contemporary Native American pottery is not always seen as art in its own right. Instead, it's sometimes seen as just "copying old forms." Bruce Bernstein, a curator, asks, "Why in the twenty-first century, should we worry about whether something is traditional or not?"

Tewa artist Jason Garcia (Oku Pin) from Santa Clara Pueblo learned pottery from his grandmother, mother, and aunts. He is the grandson of the famous potter Severa Tafoya. His work is special because he mixes traditional pottery with technology, comic books, and video games. He shows historic Pueblo warriors from the Pueblo Revolt alongside Marvel comic book heroes like Thor and Loki. Rose Bean Simpson, another Santa Clara artist, believes art can bring about big changes. She says it can raise awareness about colonization and Indigenous culture. Native American modern and contemporary art has often been left out of American art history. This is because Native American histories are often misunderstood.

Gallery of Historical Works

-

Water pot from Acoma Pueblo, around 1889–1903, at the De Young Museum.

-

Zuni Pueblo Water Jar, 1825-1850.

-

Large Cochiti Pueblo Pot, around 1880.

-

Zia Pueblo olla, showing Spanish colonial design influence.

-

Mug with an effigy, Anasazi (Ancestral Pueblo), around 1100-1300 AD, at the Peabody Museum.

-

Tesuque Pueblo water jar, around 1880–1890.

-

Zuni Pueblo olla with "heartline deer" and waterbird designs, around 1900.

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |