Quakers in the American Revolution facts for kids

The Religious Society of Friends, often called "Quakers," lived across the thirteen British colonies in North America by the mid-1700s. Many lived in Pennsylvania. The American Revolution was a tough time for them. Their religious beliefs meant they were against violence, which often clashed with the new ideas of their homeland.

At first, Quakers joined the revolutionary movement in peaceful ways. They protested with things like trade bans. But when the war started, Quakers split. Most stayed true to their pacifist beliefs and refused to support any fighting. Still, some Quakers did get involved in the war and faced consequences for it.

Contents

Quakers Across the Colonies

By 1750, Quakers lived in many colonies, including New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Delaware, New York, Maryland, and both North and South Carolina. They were especially strong in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, even controlling Pennsylvania's culture and politics.

Quaker communities stayed in touch with each other and with Quakers in Great Britain. This helped them feel united and separate from others. This separation usually didn't cause problems. Quakers often did very well, especially in Pennsylvania.

Quaker Beliefs About Peace

Quaker beliefs promoted talking things out and rejected all forms of physical violence. They accepted the government's authority but refused to support war. This is known as the Peace Testimony. Quakers who went against this belief and didn't apologize were usually asked to leave the faith.

Quaker Meetings and Rules

Many religious rules were decided at regular meetings.

- Biweekly Preparative meetings were for regular worship.

- Regional Monthly meetings handled discipline for those who broke the rules.

- Annual Yearly Meetings were the highest authority for spiritual and practical matters. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting was seen as the most important.

In the late 1700s, many Quakers held important positions in the Pennsylvania government. But when the French and Indian War began, most Quaker leaders left their government jobs. This made many Quakers want to focus more on their religion and less on worldly success. Pennsylvania Quakers became stricter about how their members behaved, and more people were asked to leave the faith for breaking rules. Other Quaker communities soon followed this example.

Early Protests Against British Taxes

Even though they were against violence, Quakers played a part in the growing problems between Britain and the colonies. Because of their connections to British Quakers and their businesses, Pennsylvania Quakers mostly wanted to find peaceful solutions in the early years of the conflict. Also, the 1763 Paxton Riots made Quakers fear religious persecution.

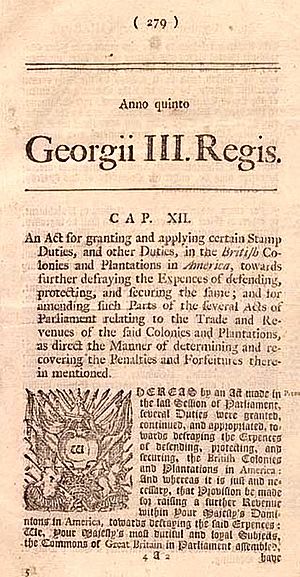

However, by 1765, some Quakers started to criticize Britain's new taxes, like the Stamp Act. Quaker merchants on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean opposed the act. Many peacefully protested its economic effects and the lack of colonial representation. Soon after the act passed, eighty Quaker merchants in Philadelphia signed an agreement not to import British goods. Quaker leaders tried to keep protests peaceful. Their calm influence helped keep events in Pennsylvania and New Jersey more peaceful than in New England.

This peace didn't last. In 1767, the Townshend Acts were passed. Again, Pennsylvania Quakers tried to stop protests against these acts. But by mid-1768, they couldn't control the strong anti-British feelings. Instead of stopping conflicts, Quakers were losing political support to groups who were okay with violence.

Quakers During the War

The American Revolutionary War caused big problems for Quakers and their pacifist beliefs. People in Pennsylvania could no longer be controlled or kept from fighting. For example, groups in Philadelphia started forming informal militias, which went against the Pennsylvania government. When the Declaration of Independence was published in 1776, Quaker communities everywhere had to deal with a situation that could only be solved with violence.

How Quaker Leaders Responded

Quakers in Pennsylvania spent a lot of time discussing the war at their Yearly Meetings. Even in 1775, they protested the increasing fighting. They said they had tried to prevent it: "We have... tried to stop our members from joining public actions... which we believed, and now find, have increased fighting and caused great trouble."

Quakers also refused to pay any taxes or fines that supported the military. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1776 made this rule clear: "It is our judgment that those who claim to be part of our religious group, and either openly or secretly pay any fine, penalty, or tax instead of serving in the war; or who allow their children, apprentices, or servants to fight, are breaking our Christian beliefs and show they are not truly with us in faith."

Some Quakers also refused to use the paper money called "Continentals," which the Second Continental Congress printed during the war. They saw this money as supporting a violent cause, which was against their religious beliefs. However, Quaker leaders never fully agreed on the Continental currency. Often, they let individuals decide for themselves whether to use it.

These rules didn't stop all Quakers from joining the war effort. As a result, many Quakers were disciplined for their involvement. One historian, Arthur J. Mekeel, found that between 1774 and 1785, 1,724 Quakers were asked to leave the faith for participating in the Revolution in some way.

Different Quaker Choices During the War

Quakers reacted to the American Revolution in many different ways. Some supported the colonies, and some were loyal to Britain. But most Quakers followed their faith and stayed out of the fighting.

Quakers Who Fought in the Revolution

Some Quakers chose to fight in the American Revolution despite their pacifist beliefs. For example, Colonel Thomas Chase served with distinction in the Revolutionary War. His story shows that some Quakers felt a strong patriotic duty.

Daniel Chase also served in the war. His family had a history of resisting unfair laws. His service continued this tradition of fighting against oppression.

Future founders of the Free Quakers also fought in the war. These Quakers believed the Revolution was a fight for a new, divinely-guided government that would make the world better. The Free Quakers were expelled from the main Quaker faith for fighting. After the Revolution, they started their own short-lived Quaker group based on their beliefs.

Several famous people in the American Revolution were also Quakers. Thomas Paine, who wrote the important pamphlet Common Sense, was born into a Quaker family. Quaker ideas likely influenced his writings. Also, American General Nathanael Greene was raised Quaker. He struggled with a big question: "Could he be loyal to the state without going against the principles of the Society of Friends?" Greene likely dealt with this conflict his whole life and never fully returned to the Quaker faith after the war.

Quaker Help Efforts

Some Quakers helped during the war without fighting. In the winter of 1775–1776, Quakers from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and other places gave money and goods to people in Boston while the British occupied the city. Both American and British forces sometimes viewed these donations with suspicion. Also, individuals sometimes helped by caring for wounded soldiers after battles or comforting prisoners of war.

How the War Affected Quakers

Quakers who refused to support the war often suffered for their religious beliefs. This happened at the hands of both non-Quaker Loyalists and Patriots. Some Quakers were arrested for refusing to pay taxes or join the army, especially in Massachusetts when more recruits were needed.

However, many more Quakers faced financial hardship. Throughout the war, British and American forces took goods from both Quakers and non-Quakers for their armies. But non-Quaker authorities also took extra property from Quakers, both for refusing to pay taxes and sometimes for opposing the war.

Sometimes, suspicious non-Quakers accused Quakers of being British supporters or spies. In August 1777, American General John Sullivan claimed to find a letter from a fake Quaker Yearly Meeting in Spanktown, NJ (now Rahway). This letter supposedly contained information about American military movements. Sullivan then wrote to John Hancock, the president of the Continental Congress, and accused Quakers of being loyalists and traitors. These "Spanktown Papers" were clearly fake, but they still turned many people against the Quakers. Sullivan's fake letters convinced a committee of the Continental Congress to send twenty important Philadelphia Quakers away to Staunton, Virginia for over seven months.

After the War

The American Revolutionary War officially ended with the 1783 Treaty of Paris. Quaker communities in the new United States of America immediately started to influence small parts of the new governments. For example, before this time, public officials usually had to swear an oath of loyalty to the state. But this rule was changed to allow "affirmations" instead. This meant Quakers could freely take part in government.

However, the Revolutionary War also negatively affected many Quakers. Partly because of the bad feelings after the "Spanktown Papers" and partly due to money problems, hundreds of Quakers left the United States starting in 1783. Many moved to Canada, settling in Pennfield, New Brunswick. Some of these Quakers had been expelled from their faith for siding with the British during the war. Others had been true pacifists. But none could stay in the United States after it became independent.

The Revolution also changed American Quakers in another major way. Before the war, many Quakers had a lot of economic and political power in several states, especially Pennsylvania and New Jersey. But the war made the pacifist Quakers feel isolated from their neighbors. Most Quakers in power began to step back from political life as early as the 1760s. The Revolution made American Quakers feel even more isolated. This made postwar Quakerism less diverse and more focused on strict religious rules. American Quakers never got back the same amount of political influence they once had.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |