René Girard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

René Girard

|

|

|---|---|

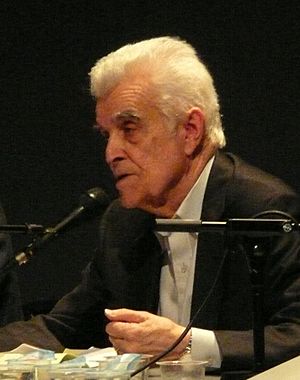

Girard in 2007

|

|

| Born |

René Noël Théophile Girard

25 December 1923 Avignon, France

|

| Died | 4 November 2015 (aged 91) Stanford, California, U.S.

|

| Education | École Nationale des Chartes (MA) Indiana University (PhD) |

| Known for | Fundamental anthropology Mimetic theory Mimetic desire Mimetic double bind Scapegoat mechanism as the origin of sacrifice and foundation of human culture Girard's theory of group conflict |

| Spouse(s) | Martha Girard |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | Académie française (Seat 37) Knight of the Légion d’honneur Commandeur of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Duke University, Bryn Mawr College, Johns Hopkins University, State University of New York at Buffalo, Stanford University |

| Doctoral students | Sandor Goodhart |

| Other notable students | Andrew Feenberg |

| Influences | Claude Lévi-Strauss, Marcel Proust, Sigmund Freud, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Ferdinand de Saussure, William Shakespeare, Friedrich Nietzsche, Miguel de Cervantes, Augustine of Hippo, Thomas Aquinas,Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, Edgar Morin, James George Frazer |

| Influenced | Raymund Schwager, James Alison, Robert Barron, Peter Thiel, Timothy Snyder, Jean-Michel Oughourlian, Jacques Ellul |

| Signature | |

|

|

René Girard (1923–2015) was a French thinker who explored many subjects. He was a historian, a literary critic, and a philosopher. His ideas are part of philosophical anthropology, which studies what it means to be human.

Girard wrote nearly thirty books. His work has influenced many fields. These include literary criticism, anthropology, theology, mythology, sociology, and economics. He is known for his ideas about human desire and conflict.

His main idea is called mimetic theory. It suggests that humans often copy what others want. This is different from thinking that our desires come only from inside us. Girard believed we learn what to desire by watching others. This copying can lead to both learning and conflict.

When people copy the same desires, they might want the same things. If these things are limited, like food or status, it can cause fights. Girard said that early human groups found a way to stop this violence. They would blame one person for all the problems. This person would be cast out or killed. This act brought peace to the group. He called this the scapegoat mechanism.

Girard also studied how this idea appears in different stories and myths. He believed that Biblical texts, unlike other myths, show the innocence of the victim. This changes how we understand conflict and justice.

Contents

René Girard's Early Life

René Girard was born in Avignon, France, on December 25, 1923. His middle name, Noël, means "Christmas" in French. His father, Joseph Girard, was also a historian.

René studied medieval history in Paris. In 1947, he moved to the United States for a fellowship. He spent most of his career there. He earned his PhD in 1950 from Indiana University. His early work focused on French literature.

René Girard's Career and Major Works

Girard taught at several universities. These included Duke University and Bryn Mawr College. In 1957, he joined Johns Hopkins University. He became a full professor there in 1961.

His first important book, Deceit, Desire and the Novel, was published in 1961. Later, he wrote Violence and the Sacred (1972). Another key book was Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1978).

In 1981, Girard moved to Stanford University. He taught there until he retired in 1995. During this time, he published Le Bouc émissaire (The Scapegoat) in 1982. He also wrote A Theatre of Envy: William Shakespeare in 1991.

In 2005, René Girard was elected to the Académie française. This is a very high honor in France.

Understanding Girard's Ideas

What is Mimetic Desire?

Girard noticed something interesting about characters in novels. He saw that their desires were often not their own. Instead, they copied what other characters wanted. He called this mimetic desire.

This means we often borrow our desires from others. Imagine you want a new video game. Maybe your friend has it and talks about how great it is. Your desire for the game might come from seeing your friend enjoy it.

Girard explained this with a triangle:

- You (the subject)

- The object (the video game)

- Your friend (the model or mediator)

You want the game because your friend, the model, wants it or has it. You are drawn to the model through the object. Sometimes, you might even want to be like the model.

Girard called this desire "metaphysical." It's not just about needing something. It's about wanting to be like someone else. This can lead to wanting the same qualities or status as your model.

When the model is someone far away, like a fictional hero, it's "external mediation." Think of Don Quixote, who copied the desires of a knight from a book.

When the model is someone close to you, like a friend, it's "internal mediation." This can cause problems. The model becomes a rival for the same object. The more you both want it, the more valuable it seems. This is often seen in novels by authors like Stendhal and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Girard's idea of mimetic desire has gained support. Modern research in psychology and neuroscience shows how much humans imitate each other.

The Scapegoat Mechanism

Girard believed that copying desires can lead to conflict. If many people want the same thing, they will fight over it. This fighting can spread and become very dangerous for a group.

He suggested that early human groups found a way to stop this violence. They would all turn their anger and blame onto one person. This person would become the scapegoat. The group would then unite against this single victim.

When the scapegoat was removed (often killed), the violence would stop. The group would feel calm and peaceful again. Because the victim brought peace, they were often seen as sacred or even a god. This process, where one person is blamed to bring peace, is called the scapegoat mechanism.

Girard argued that this mechanism is at the root of many ancient religions and cultures.

The Bible and the Scapegoat

Girard believed that the Biblical texts are special. They reveal the truth about the scapegoat mechanism. In the Gospels, for example, the story of Jesus's death shows an innocent victim. The text clearly states that Jesus is not guilty.

This is different from other myths, like the story of Romulus and Remus. In those myths, the community's story depends on the victim being seen as guilty. By showing the victim's innocence, the Bible makes it harder for the scapegoat mechanism to work.

Girard thought that this revelation in the Bible has slowly changed human society. It has made us more aware of victims and less able to ignore injustice. However, this also means societies can no longer easily use the scapegoat mechanism to create peace. This can lead to new kinds of conflicts.

How René Girard's Ideas Influence Others

Girard's ideas have spread widely.

Influence on Economics

His mimetic theory has been used to study economics. Some thinkers believe that economic theories can be like myths. They suggest that mimetic rivalry (people copying each other's desires for wealth) can lead to conflict.

One idea is that the gift economy developed to stop this rivalry. Instead of fighting, people would give gifts. This created a positive cycle of giving and receiving.

Influence on Literature

Many writers have been influenced by Girard. J. M. Coetzee, a Nobel Prize winner, often explores mimetic desire and scapegoating in his novels. His book Disgrace even has a character who talks about the history of scapegoating, similar to Girard's views.

Influence on Theology

Girard's work has also impacted theology (the study of religion). Theologians like James Alison and Robert Barron have used his ideas. They explore how mimetic desire relates to concepts like original sin and the meaning of Jesus's life and death. Father Elias Carr, an Augustinian Canon of Klosterneuburg, and author of “I Came to Cast Fire”, was heavily influenced by the writings of Girard.

Criticisms of Girard's Ideas

Like any big idea, Girard's theories have faced criticism.

Was He Original?

Some critics say that Girard wasn't the first to notice that people imitate each other's desires. Thinkers like Gabriel Tarde and La Rochefoucauld had similar ideas. Even Thomas Hobbes and Baruch Spinoza wrote about how people desire the same things, leading to conflict.

Girard sometimes said his ideas were completely new. But at other times, he acknowledged earlier thinkers.

How He Used Evidence

Some scholars argue that Girard's interpretations of myths and Bible stories are not always accurate. For example, they say he sometimes ignores parts of the Gospels that don't fit his theory. They suggest his work is more like a philosophy than a strict science.

What About Non-Mimetic Desires?

Critics also ask if all desire is mimetic. What about desires that are not copied, like unique interests or taboo desires? If everyone just copies, who is the first person to desire something new? Girard's theory has been updated to include positive forms of imitation, but this raises new questions about how cultures begin.

Anthropology and Religion

Some anthropologists disagree with Girard's "one-size-fits-all" approach to cultures. They argue that he might miss the unique ways different societies work.

In religion, some find his view of Jesus as purely a human event, without divine purpose, unconvincing. However, others, like Roger Scruton, note that Girard's view still sees Jesus as divine because he understood the need for his death and forgave his persecutors.

René Girard's Personal Life

René Girard was married to Martha McCullough from 1952 until his death. They had three children.

Girard converted to Catholicism later in his life. He was a committed Catholic.

He passed away on November 4, 2015, in Stanford, California, at the age of 91.

Honours and Awards

René Girard received many awards and honors throughout his life:

- He received several honorary degrees from universities around the world.

- He won the Prix Médicis essai for his book about Shakespeare.

- He was awarded the Dr. Leopold Lucas Prize.

- He was elected to the Académie française in 2005.

See also

In Spanish: René Girard para niños

In Spanish: René Girard para niños

- James George Frazer

- Mimetics

- Simulacrum

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |