Sofia Gubaidulina facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sofia Gubaidulina

|

|

|---|---|

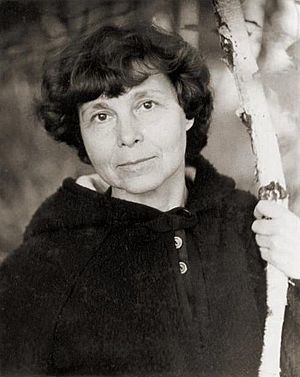

Gubaidulina in 1981

|

|

| Born | 24 October 1931 Chistopol, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union

|

| Died | 13 March 2025 (aged 93) Appen, Germany

|

| Occupation | Composer |

Sofia Gubaidulina (born October 24, 1931 – died March 13, 2025) was a famous composer from the Soviet Union and Russia. She created many pieces of modern spiritual music. She wrote a lot of different types of music. This included pieces for small groups of instruments, large orchestras, and choirs.

Her music often explored the differences between Western and Eastern sounds. It was known for using new ways with very small musical steps (microtonality) and all notes (chromaticism). She focused on rhythm more than traditional musical shapes. Her music also used contrasting keys. People praised her compositions for their strong feelings. She once said her music aimed to connect the "broken" parts of life with a smooth, flowing feeling. Sofia Gubaidulina was one of the most important composers from the former Soviet Union. Her work became very popular around the world. Her first big success was her violin concerto called Offertorium (1980).

Contents

Early Life and Musical Beginnings

Sofia Gubaidulina was born on October 24, 1931, in Chistopol. This city is now in the Republic of Tatarstan, Russia. Her father was a Volga Tatar and worked as a surveyor and engineer. Her mother was of Polish-Jewish background and was a teacher.

Sofia started learning music when she was five years old. She played on a small grand piano. She became very interested in how music is made. While studying at the Children's Music School, she found spiritual ideas in the music of great composers. These included Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven.

She had to keep her spiritual interests a secret. This was because the Soviet Union was against religion. These early experiences shaped her view of music and spirituality. She believed they were very similar. This explains why she later wrote music that explored spiritual ideas.

Her Journey as a Composer

Sofia Gubaidulina studied music at the Kazan Conservatory. She finished her studies there in 1954. When she was starting her career, most Western modern music was not allowed to be studied. One exception was the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók.

There were even searches in student dorms for banned music scores. Scores by Stravinsky were especially sought after. But Gubaidulina and her friends still found and studied modern Western music. She later said, "we knew Ives, Cage, we actually knew everything secretly."

She continued her studies at the Moscow Conservatory until 1963. Her music was sometimes called "irresponsible" by Soviet officials. This was because she explored different ways of tuning instruments. However, she was supported by the famous composer Dmitri Shostakovich. He encouraged her to keep going, even when others disagreed.

She was allowed to express her modern style in music for documentary films. One film was On Submarine Scooters (1963). She also wrote the music for the 1967 Soviet animated film Adventures of Mowgli. This film was based on Kipling's The Jungle Book.

In the mid-1970s, Gubaidulina started a group called Astreja. This group played folk instruments and improvised music. In 1979, she was put on a blacklist. This happened because her music was seen as too "noisy" and not connected to "real life."

Gubaidulina became famous around the world in the early 1980s. This was partly thanks to violinist Gidon Kremer. He strongly supported her violin concerto Offertorium. By the late 1980s, she was internationally recognized. She later wrote a piece as a tribute to the poet T. S. Eliot. It used words from his work Four Quartets.

In 2000, she was asked to write a piece for a special project. This project honored Johann Sebastian Bach. Her contribution was Johannes-Passion, which means "Passion according to John". In 2002, she wrote Johannes-Ostern ("Easter according to John"). These two works together tell the story of Christ's death and resurrection. It is her longest work.

In 2003, she was the first female composer to be featured at the Rheingau Musik Festival. Her piece The Light at the End was played before Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 at the 2005 Proms concert series. In 2007, her second violin concerto, In Tempus Praesens, was performed. A film called Sophia – Biography of a Violin Concerto showed how it was created.

In 2023, her Sonata for Violin and Cello was performed in Kazan. She was a composer-in-residence at the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in 2019. She was also a member of important music academies in Berlin, Hamburg, and Sweden.

Personal Life and Influences

Sofia Gubaidulina was a very religious person. She was a member of the Russian Orthodox Church. In 1973, she faced a dangerous incident in her Moscow apartment building. Her friends later thought it might have been related to her being a dissident.

After the Soviet Union ended, she moved to Appen, Germany, in 1992. The Steinway grand piano in her home was a gift from the famous cellist Rostropovich. She was married three times. Her second husband was the writer Nikolai Bokov.

Gubaidulina stopped composing for a while in 2012. This was after her third husband, her daughter, and her friend and fellow composer Viktor Suslin passed away. Sofia Gubaidulina died from acute heart failure at her home in Appen on March 13, 2025, at the age of 93.

Her Unique Musical Style

Exploring Spiritual Ideas in Music

Gubaidulina saw music as a way to escape the difficult political situation in Soviet Russia. She connected music with spiritual ideas and a deep longing within the human soul. She tried to capture this longing in her works. These spiritual ideas appeared in her music in different ways. For example, in her piece "Seven Words," she wrote bowing instructions that made the performer draw a cross shape.

She used elements from electronic music and improvisation. She combined different sounds and used unusual instruments. She also used traditional Russian folk instruments in her solo and chamber pieces. Examples include De profundis for bayan (a type of accordion) and In croce for cello and organ or bayan. She even used the koto, a traditional Japanese instrument, in her work In the Shadow of the Tree.

Gubaidulina was fascinated by percussion instruments. She felt their sounds had a mysterious quality. She believed they showed the freedom of human spirit. In an interview, she said percussion instruments "contain the essence of existence." She explained that percussion sounds are "at the boundary between palpable reality and the subconscious."

She loved to experiment with new ways of making sounds. She also used unusual combinations of instruments. Examples include her Concerto for Bassoon and Low Strings (1975) and The Garden of Joy and Sorrow for flute, harp, and viola (1980).

Gubaidulina admired composers like J. S. Bach, Wagner, and Anton Webern. She also liked music from the 16th century. Beyond music, she was influenced by thinkers like Carl Jung and Nikolai Berdyaev. Berdyaev's works were not allowed in the USSR.

She also drew ideas from different types of poetry. This included ancient Egyptian poetry, Persian poetry, and German poetry. She also used works by Eliot and contemporary Russian poetry.

How Her Music Sounds

Gubaidulina was a deeply spiritual person. She saw "religion" as a way to "re-connect" or "re-bind" with a higher power. She believed music's most important job was to help with this re-connection. She found this connection through her art. She created musical symbols to express her beliefs.

Her music often uses unusual combinations of instruments. For example, In Erwartung ("In Anticipation") combines many percussion instruments with a saxophone quartet. Her melodies often use many chromatic notes, which are very close together. She did not use long, flowing melodies as much.

She often thought of musical space as a way to connect with the divine. She showed this by avoiding clear "steps" in pitch. She used very small musical steps (quarter tones) and frequent glissandi (sliding between notes). This showed there were no "steps" to the divine. She also used strong contrasts between chromatic (all notes) and diatonic (scale notes) sounds. These represented darkness versus light, or human versus divine.

Short musical ideas helped her create a story that felt open-ended. Another important technique was her use of harmonics. These are high, clear sounds on string instruments. She explained that harmonics on string instruments can show a "transition to another plane of existence." She said, "And that is joy." Her piece Rejoice! uses harmonics to show joy as a higher spiritual state.

Her harmonies did not follow traditional rules of tonal centers. Instead, she used groups of notes played close together (clusters). She also focused on how different musical lines interacted. For example, in her Cello Concerto Detto-2 (1972), she used intervals that started wide and became narrower.

Gubaidulina believed that rhythmic structures should shape the entire piece, not just small parts. She often used the Fibonacci sequence or the golden ratio to build the timing of her compositions. In these sequences, each number is the sum of the two before it (like 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8...). She felt this mathematical pattern showed balance in her music. She believed this abstract idea was key to her musical expression. The golden ratio points in her pieces were always marked by a special musical event.

She started using the Fibonacci sequence to structure her music in the early 1980s. This helped her create new musical forms that she felt were more spiritual. She also experimented with other similar number sequences. She even said, "It is a game!"

A close friend and colleague, Valentina Kholopova, described Gubaidulina's form techniques. She mentioned "expression parameters" like articulation, melody, rhythm, texture, and composition. These parameters exist on a scale from consonance (pleasant sounds) to dissonance (unpleasant sounds). For example, a smooth, connected sound (legato) is consonant. A short, detached sound (staccato) is dissonant.

Kholopova noted that Gubaidulina's music often uses a "mosaic form." This means it's made of many small pieces held together by the Fibonacci sequence. These pieces "modulate" or shift between consonant and dissonant sounds. This technique is very clear in her Ten Preludes for Solo Cello.

Piano Music

Gubaidulina's piano music was written earlier in her career. It includes pieces like Chaconne (1962) and Piano Sonata (1965). Some titles show her interest in older musical styles, like those from the Baroque period.

Later, she used the piano in ways inspired by John Cage. He would place objects like metal and rubber on piano strings. This changed the instrument's sound.

Awards and Recognition

Sofia Gubaidulina received over 40 awards and honors. In 2013, she received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement in Music at the Venice Biennale. In 2016, she won the BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award for contemporary music. The judges praised her "outstanding musical and personal qualities" and the "spiritual quality" of her work.

Her 90th birthday in October 2021 was celebrated by the Gewandhaus Orchestra in Leipzig. They released three of her pieces. She was also honored with a week of chamber and orchestral music. In November, she was featured as Composer of the Week on BBC Radio 3.

Major Prizes

Some of the important prizes Gubaidulina received include:

- Rome International Composer's Competition (1974)

- Prix de Monaco (1987)

- Premio Franco Abbiati (1991)

- Heidelberger Künstlerinnenpreis (1991)

- State Prize of the Russian Federation (1992)

- Ludwig-Spohr-Preis der Stadt Braunschweig (1995)

- Kulturpreis des Kreises Pinneberg (1997)

- Praemium Imperiale in Japan (1998)

- Léonie Sonning Music Prize in Denmark (1999)

- Preis der Stiftung Bibel und Kultur (1999)

- Goethe-Medaille der Stadt Weimar (2001)

- Polar Music Prize in Sweden (2002)

- Bach Prize of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (2007)

- Knight Commander's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (2009)

Honorary Degrees and Positions

In 2001, Gubaidulina became an honorary professor at the Kazan Conservatory. In 2005, she was chosen as an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She received honorary doctorates from Yale University in 2009 and the University of Chicago in 2011. In 2017, she received an honorary doctor of music degree from the New England Conservatory.

Discography

- Solo Piano Works (1994: Sony SK 53960). This album features "Chaconne" (1962), "Sonata" (1965), and "Musical Toys" (1968), played by Andreas Haefliger. It also includes "Introitus": Concerto for Piano and Chamber Orchestra (1978), with Andreas Haefliger and the NDR Radiophilharmonie.

- The Canticle of the Sun (1997) and Music for Flute, Strings, and Percussion (1994). The first piece is performed by cellist and conductor Mstislav Rostropovich and London Voices. The second features flutist Emmanuel Pahud and the London Symphony Orchestra.

- Johannes-Passion (2000). This recording features several singers and choirs. It includes the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra conducted by Valery Gergiev. This was a live recording of the world premiere in Stuttgart.

See also

In Spanish: Sofiya Gubaidúlina para niños

In Spanish: Sofiya Gubaidúlina para niños