St Mary Magdalene's Church, Battlefield facts for kids

Quick facts for kids St Mary Magdalene's Church, Battlefield |

|

|---|---|

St Mary Magdalene's Church, Battlefield, from the southeast

|

|

| 52°45′02″N 2°43′25″W / 52.7506944°N 2.7235849°W | |

| OS grid reference | SJ 512 172 |

| Location | Battlefield, Shropshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | Churches Conservation Trust |

| History | |

| Authorising papal bull | 30 October 1410, from John XXIII |

| Status | Chantry 1406, Collegiate church by 1410–1548 Parish church, c.1548–1982 |

| Founded | 28 October 1406 (grant of site authorised) |

| Founder(s) | Roger Ive Richard Hussey Henry IV |

| Dedication | Saint Mary Magdalene |

| Dedicated | In or before March 1409 |

| Events | c.1500: West tower completed. 1548: College and chantry dissolved. 1861–62: Major restoration. |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Redundant |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* |

| Designated | 19 September 1972 |

| Architect(s) | Samuel Pountney Smith (restoration) |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Gothic, Gothic Revival |

| Groundbreaking | 1406 |

| Completed | 1862 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Limestone, tiles and slates on roofs |

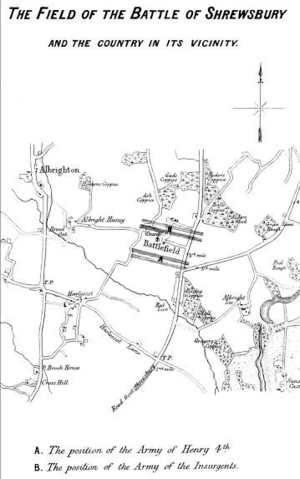

St Mary Magdalene's Church is located in the village of Battlefield, Shropshire, England. It is dedicated to Mary Magdalene, a companion of Jesus. This church was built on the very spot where the famous Battle of Shrewsbury took place in 1403. This battle was fought between King Henry IV and Henry "Hotspur" Percy.

The church was first planned as a chantry. This was a special place for prayers and remembering those who died in the battle. It is believed to be built over a large burial pit for the fallen soldiers. Originally, it was a collegiate church, meaning it had a group of chaplains (priests) who lived and worked together. Their main job was to hold daily services for the dead. Roger Ive, the local priest, is often seen as the church's founder. However, King Henry IV also gave a lot of support and money to the church.

After 1548, the college and chantry were closed down. The building then became the local parish church. Over time, it fell into disrepair. There were some attempts to fix it in the mid-1700s. A major restoration happened in the Victorian era (1800s). This restoration was quite debated at the time. Today, St Mary Magdalene's is a redundant Anglican church. This means it is no longer used for regular services. It is protected as a Grade II* listed building and is cared for by the Churches Conservation Trust.

Contents

Building the Church

Who Started It?

For a long time, people thought King Henry IV was the main founder of the church. He even said so in a document from 1410. Historians in the 1700s and 1800s also believed this. They thought the king built it to thank God for his victory at the Battle of Shrewsbury. The battle happened on the day before St Mary Magdalene's Day (July 22nd), which is why the church was dedicated to her.

However, a historian named John Brickdale Blakeway found out the real story. He discovered that the idea for the church came from local people. These were Roger Ive, the local rector (priest), and Richard Hussey, who owned the land. Blakeway's notes were published much later.

The church's true beginning was in 1406. On October 28th, King Henry IV gave permission to Richard Hussey to donate two acres of land for the church. This land was in Hateley Field. The purpose was to build a chantry chapel. Here, priests would sing masses for the souls of the king, his family, and everyone killed in the battle. Roger Ive likely suggested building the church, and Hussey was happy to give the land.

Roger Ive was a priest from Leaton. He became the rector of Albright Hussey in 1398. He also held another church job nearby. Even though he had two jobs, they didn't pay much. Ive was a strong person who guided the church's development until he retired in 1447.

Richard Hussey was a landowner in Shropshire. He wasn't a nobleman, but he had some wealth. In 1415, he transferred some of his lands and church rights to Roger Ive and other priests. This was a common way to manage property back then. It could help with taxes and give more freedom in how property was used.

King Henry IV's Support

The Battle of Shrewsbury actually covered a wide area, not just Hateley Field. After the church's initial founding, King Henry IV became more involved. In 1409, he officially made the chapel a permanent chantry dedicated to Mary Magdalene. He planned for it to have eight chaplains and a Master. He also promised to give it the right to appoint the priest and collect tithes (church taxes) from St Michael's Church in Lancashire. The king even ordered lead for the roof in August 1409, showing the church was still being built.

Becoming a Royal Church

In 1410, the church's status changed again. Roger Ive gave the land to the king. Historians believe the king wanted to be seen as the main founder. This was important for him, especially since he had taken the throne by force.

On May 27, 1410, the king officially re-founded the chapel with a royal charter. This document set up a community of five chaplains and a master. They were to pray daily for the souls of the king, Richard Hussey and his wife, and those who died in the battle. Roger Ive and future rectors would hold the master's position. The church also gained the right to appoint priests and collect tithes from other churches in Shrewsbury and Shifnal. It was also allowed to hold a fair every year on July 22nd, St Mary Magdalene's Day. The master was also made free from most taxes.

Papal Approval

Roger Ive asked the Pope to confirm the church's foundation. This approval came from John XXIII in October 1410. His official document was the first to call Battlefield Church a "college of priests." It confirmed all the king's grants, except for the fair.

Dedication to Mary Magdalene

The church was dedicated to Mary Magdalene. This decision was made by 1409, if not earlier. The Battle of Shrewsbury happened on July 21st, the day before St Mary Magdalene's Day (July 22nd). The unknown soldiers who died would have been buried on her feast day.

A seal from the college, found on a document from 1530, clearly shows the dedication to Saint Mary Magdalene. The festival of Mary Magdalene was celebrated every year, along with the fair.

Life at the College

By the 1400s, colleges of secular clergy (priests who didn't live in monasteries) were a common type of new religious group. Unlike some larger colleges where priests might not live there, the priests at Battlefield were expected to live together and perform their duties.

Living Together

The chaplains at Battlefield first lived in a three-story building next to the south side of the chancel (the area around the altar). You can still see some remains of this building today. Later, in 1478, Roger Philips built new rooms for them. He left these rooms to the chaplains, asking them to remember him in their prayers. It's also possible a room in the church tower, which had a fireplace, was used by a priest.

Roger Ive's will, written in 1444, describes the chaplains' daily life. They lived in one house with a shared kitchen and dining room. They had a large dining table and plenty of cooking equipment. Ive left all these items to them. They were expected to eat their two daily meals together in the common dining hall. They also had to get permission from the Master to leave the college. If a chaplain had a wife or partner, they would be expelled.

The chaplains were paid eight marks a year. Ive wanted them to get a pay raise if they said special prayers for his soul. These prayers were in addition to their regular masses for the kings, the Hussey family, and the battle-dead.

Daily Prayers

The chaplains' main duties involved daily prayers and masses for the dead. These prayers followed the "Use of Sarum," a common prayer style in England at the time. They said specific prayers for Henry IV, Henry V, the Hussey family, Roger Ive, and all those who died at the Battle of Shrewsbury. They also held two masses every day.

Ive's will also listed the items needed for their services. These included three silver-gilt chalices (cups for communion), a silver-gilt pax board (used for the "kiss of peace"), and two silver cruets (small containers for water and wine). They also had three brass bells in the bell tower.

The college had a good collection of books. These included breviaries (prayer books), missals (books for Mass), and a psalter (book of psalms). They also had many vestments (special clothes for services) in red velvet and white silk.

Other Activities

A witness in 1581 remembered "going to school to the college of Battlefield" when he was a boy. This suggests the college might have provided education for local children. A special school book from Battlefield College is now in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Roger Ive's will also mentioned that any extra money from donations for the bell tower should go to the poor and their almshouse (a house for poor people). This shows there was an intention to help the community. However, later records from 1535 do not show any money spent by the college on education or a hospital. If they existed, they must have stopped before the college closed.

Challenges and Rules

The chaplains were priests living near ordinary people. They faced challenges from community and political life. Roger Ive even got special permission from King Henry VI for the college to handle many legal matters within its own land. This was because royal and local officials were bothering the chaplains with fines and demands. The king wanted them to have peace to focus on their religious duties.

The chaplains' pay was not very high. Even with extra payments, it wasn't a lot for their daily duties. However, they were not idle. They had a garden and a fish pond, which might have helped them.

Sometimes, the Master of the college held many other church jobs at the same time. For example, Adam Grafton, who was Master from 1478 to about 1518, held many positions. He was probably rarely at Battlefield. In 1518, an inspection found the college struggling financially, partly because they had to pay a pension to the retired Adam Grafton. But they were generally following the rules. By 1524, things were not as good.

Money and Property

Roger Ive was mostly happy with the money and property the college had by 1410. They only got a few more things later. Most of the college's properties were in Shropshire, near Watling Street. The only exception was St Michael's Church in Lancashire.

Lands and Rights

The college received land and rights from various donors, mostly King Henry IV and Richard Hussey. These included the church site itself, and the right to appoint priests and collect tithes from several other churches and chapels. These were St Michael's Church in St Michael's on Wyre (Lancashire), St Andrew's Church in Shifnal, Dawley Church, St Michael's Chapel at Shrewsbury Castle, St Julian's Church in Shrewsbury, and Ford Chapel. The college also bought small areas of land in Harlescott and Albright Hussey, and a township called Aston near Shifnal.

Sometimes, it took a while for the college to actually get control of these properties. For example, St Michael's Chapel at Shrewsbury Castle was only given to them in 1416 or 1417.

Legal Battles

The Masters of Battlefield were ready to go to court to protect their property and income. For example, in 1418, Roger Ive had to defend the college against a claim for annual rent from the Archdeacon of Richmond. Later, Ive also fought to keep the college free from taxes. In 1461, Roger Philips, another Master, had a dispute with Haughmond Abbey over tithes from a deer park. They eventually settled this with a mediator.

Raising Money

The annual fair was a good way to make money, and Battlefield Church also attracted pilgrims. To encourage more visitors and donations, the church asked for indulgences. An indulgence was a special church grant that reduced time in purgatory for those who supported the college.

In 1418, the Bishop of Hereford granted a 40-day indulgence. In 1423, Pope Martin V granted a much larger indulgence of five years and five "quarantines" (40-day periods) to those who visited the chapel and donated. In 1443, Pope Eugenius IV extended this to seven years and seven quarantines. In 1460, the Bishop of Lichfield also granted a 40-day indulgence for donations.

When these indulgences didn't bring enough money, the college sought help from the new king, Edward IV. In 1461, Edward IV allowed the Master, Roger Philips, to send out a special representative, Thomas Brown, to collect money in Staffordshire, Derbyshire, and Warwickshire. The king even protected Brown and his team. This fundraising continued, with later bishops also giving permission for proctors (representatives) to collect donations. As late as 1525, King Henry VIII allowed three proctors to collect alms.

Financial Records (1535)

Under the Tudor dynasty, the college lost its tax exemption. Records show tax payments were made from 1519 onwards. In 1530, the college leased half its land at Aston for a very low price.

In 1535, a survey called the Valor Ecclesiasticus recorded the college's income. Its total income was about £56. The largest part came from St Michael's on the Wyre. The Master, John Hussey, received £34, and the other five chaplains each received £4. This survey led to the closing of smaller monasteries, but not Battlefield Church at that time.

Masters of the College

Here are some of the known Masters or wardens of Battlefield College:

| Name | Years in Charge | Important Events | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roger Ive or Yve | 1409–1447 | He is known as the true founder of Battlefield College. He worked to make sure the college would last. He also got the college special rights to handle legal matters in its area. | |

| Henry Bastard | 1447–1454 | He was a Master of Arts. | |

| Roger Phelips or Philips | 1454–1478 | He was told not to control other chapels. He got permission from the bishop and King Edward IV to raise money for the college. He also settled a land dispute with Haughmond Abbey. | |

| Adam Grafton | 1478–1518 | He was an important church leader and served as chaplain to two princes. He held many church jobs at the same time. He likely finished the church tower, where his name is carved. | |

| John Hussey | 1518–1524 | He leased out some of the college's land for a long time. | |

| Humphrey Thomas | 1524–1534 | He got permission from King Henry VIII to raise funds because the college was struggling financially. He also granted long leases for land. | |

| John Hussey | 1534–1548 | He continued the policy of long leases. He had to report the college's value for the Valor Ecclesiasticus. He retired with a pension when the college closed. |

Closing of the College

End of Chantries and Colleges

In 1545, a law called the Dissolution of Colleges Act 1545 gave all colleges, free chapels, and chantries to the king. Commissioners were sent to inspect them. In 1546, Battlefield's finances were similar to 1535. The warden, John Hussey, earned less than before. The "five brethren" (chaplains) still earned eight marks each. The report clarified that Battlefield was not the main parish church, but was part of Albright Hussey parish.

However, the college wasn't closed immediately. A new law, the Dissolution of Colleges Act 1547, was passed in 1547, during the reign of King Edward VI. Another inspection followed. This time, the report said Battlefield *was* a parish church and had 100 people needing a priest. John Hussey's salary was even lower, and he was about 40 years old. Only four chaplains were named, and one was 92 years old! The college had not spent money on preachers, schools, or the poor that year.

Battlefield College likely closed in early 1548. John Hussey received a pension. The church then became the parish church for Albright Hussey. One of the former chaplains, Edward Shord, stayed on as the curate (local priest) with a salary.

Selling the Properties

The properties of the former college were sold by the Court of Augmentations. This was a government department that handled church lands. The asking price was usually 20 times the yearly value. Sir Walter Mildmay, a surveyor for the Court, managed the sales.

John Cupper, a collector for the Court, and Richard Trevor, bought many of the Battlefield College properties in 1549 for a large sum of money. These included St Julian's Church, the college site, Albright Hussey chapel, tithes from Harlescott, market stalls, and the income from the annual fair. They then sold these properties to others. For example, Thomas Ireland bought his tithes from John Cowper. The Hussey family eventually bought back their old land.

Other properties, like those in Lancashire, were sold in 1549. The township of Aston near Shifnal was sold in 1553. The Crown kept control of Shifnal rectory until the reign of James I.

Decay and Restoration

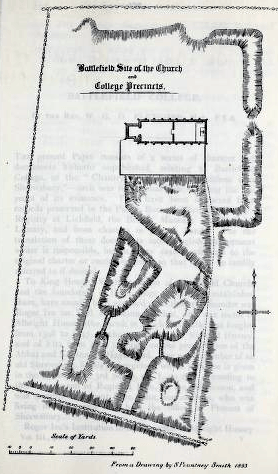

The college buildings were no longer used and were probably torn down. Their materials might have been used for other buildings. To the south of the church, some dips in the ground might be where the college's fishponds once were.

As the population decreased, the church was still used, but it got worse over time. The roof was fixed in 1749, but later the nave (the main part of the church) roof fell in. In the late 1700s, the nave was abandoned. Only the chancel (the area around the altar) was repaired in a neoclassical style.

Drawings from the mid-1800s show that the church wasn't completely without a roof. The chancel was still used for services. Richard Brooke visited the church in 1856. He described the nave as "roofless and dilapidated" but noted that its walls and window frames were still standing. He warned against too much restoration, saying it could destroy the church's historical value.

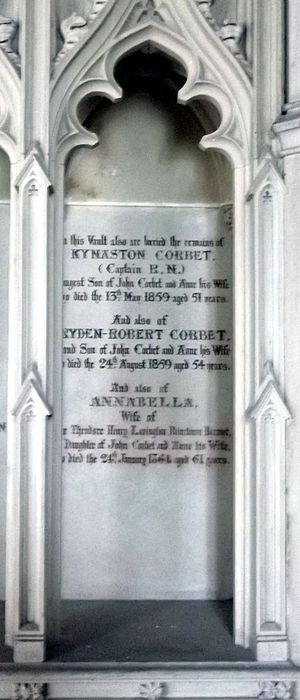

In 1859, Lady Annabella Brinckman inherited the church site. She hired architect Samuel Pountney Smith to restore the church and build a mortuary chapel (a chapel for the dead). This work happened between 1860 and 1862.

The Churches Conservation Trust praises the restoration, saying Pountney Smith "saved the church from ruin." They highlight features like the "magnificent hammerbeam roof." However, some experts, like David Cranage, had reservations. He noted that much of the church's visible details, like the parapets, pinnacles, roof, screen, and seats, were modern additions from the 1861–62 restoration. Pountney Smith often rebuilt most of the church while keeping the medieval west tower. The hammerbeam roof, while impressive, was not medieval.

Lady Brinckman died in 1864, and the church site went to the Corbet family. After more than a century as a parish church, the building was declared redundant in 1982. It is now cared for by the Churches Conservation Trust. The tower and nave were repaired in 1984. The church remains a memorial chapel for the battle-dead, with an annual service.

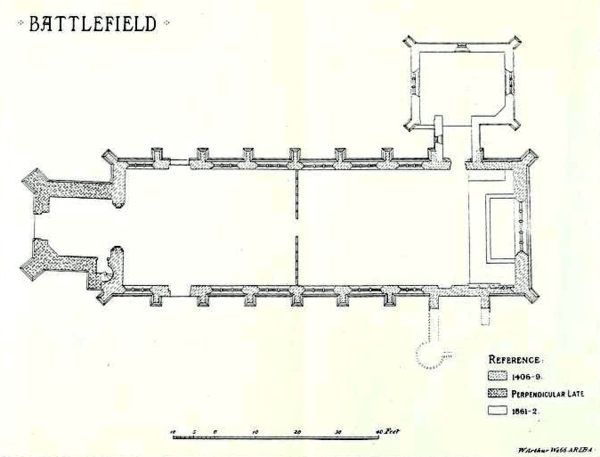

Church Design

Location and Surroundings

The church faces almost exactly east. It stands in a churchyard, with the main entrance usually from the north. The old college buildings were to the south, but only small remains of their foundations are left. Further south, there are also remains of a former round tower. Some gravestones in the churchyard have carvings from the Victorian era and the Art Deco period. At the north entrance, there is a lychgate (a covered gateway to a churchyard). This was built during the Victorian restoration using wood from another church.

Outside the Church

The church is built from limestone with roofs made of tiles and Welsh slates. It has a simple rectangular shape, with a five-section chancel and a four-section nave, both the same width. There is a tower at the west end and a vestry (a room for priests' robes) to the north-east.

The tower is almost as wide as the nave and has two levels. It has diagonal buttresses (supports) and a square staircase turret. The name of Master Adam Grafton is carved on a shield high on the east side of the tower. The arms of Sir John Talbot, 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury are also on the tower. The lower part of the tower has a west door and a two-light window above it. The upper part has two bell openings on each side. At the very top, there is a decorative band, a battlemented (castle-like) top, and pinnacles (small spires) at the corners.

Along the main body of the church, the sections are separated by tall buttresses. Most of the window designs are in the Decorated style, added during the restoration. However, some windows still have their original designs. The east window is in the Perpendicular style and has five lights (sections). Above this window, in a niche, is a statue of King Henry IV. The nave's parapet (low wall at the roof edge) is plain, while the chancel's is decorative with openwork quatrefoils (four-leaf shapes). Around the church, there are gargoyles shaped like mythical beasts and soldiers, most of which are modern. The vestry has a battlemented top, and on its wall is the carved crest of the Corbet family (two crows).

Inside the Church

There is no wall or clear break between the nave and the chancel inside the church. The large screen that you see when you enter was put in by Pountney Smith during the Victorian restoration. This screen is a bit controversial because it would only have been strictly needed if Battlefield had been a parish church from the start, separating the public (laity) in the nave from the priests in the chancel. But it only became a parish church after the Reformation.

The famous hammerbeam roof by Pountney Smith is supported by the original stone corbels (projections from the wall). One corbel has a carving of a Green Man (a face made of leaves). The roof is decorated with carved shields, pendants, and patterned panelling. These shields show the arms of knights who fought in the battle. The church floor is covered with patterned encaustic tiles made by Maw of Ironbridge.

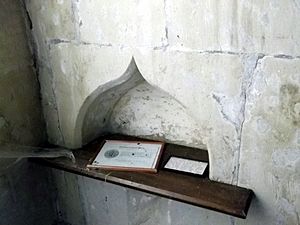

In the southeast part of the chancel, there is a triple sedilia. These are three stone seats for the priest, deacon, and sub-deacon during services. There is also what's left of a piscina (a basin for washing communion vessels). A blocked doorway once led to the chaplains' living quarters, giving them quick access to the chancel. On the chancel's south wall, there is a marble tablet that serves as a war memorial for local men who died in the First and Second World Wars. The doorway on the north side of the chancel leads to the vestry, which used to be the Corbet family's mortuary chapel.

The reredos (a screen behind the altar) was designed by Pountney Smith. It has high relief sculptures showing the birth of Jesus, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection. The font (for baptisms) and the pulpit (for sermons) were also designed by Pountney Smith. The pulpit is made of stone with a white marble panel showing Moses striking a rock for water. The top of the font is eight-sided and carved with angels. The ends of the wooden pews are carved with birds and animals.

On the north side of the chancel is an oak pietà or Lady of Pity. This carving, probably from the mid-1400s, shows Mary holding the body of Jesus after his crucifixion. It is about 1.15 meters tall and hollowed out behind. Some believe it came from another church, but there's no proof. Historians think it was originally made for Battlefield College. It was very fitting for a church dedicated to remembering the dead, as it showed sorrow and sympathy.

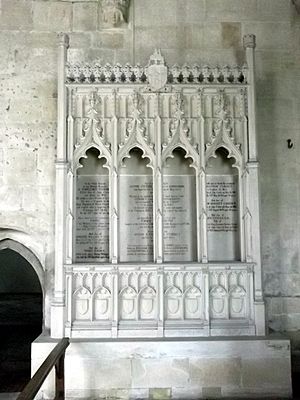

The vestry has stained glass from different times. Some is original from the church, possibly from the 1430s-1440s. There's also some early 1500s French glass from Normandy. The main church windows have glass by Lavers and Barraud from 1861 to 1863. The east window in the chancel shows Mary Magdalene. The north and south windows show the twelve apostles. The west window of the tower shows Christ and John the Baptist. The church also has a wall memorial to the Corbet family, hatchments (diamond-shaped funeral shields), and Victorian gas lights.

See also

- Listed buildings in Shrewsbury (outer areas)

- List of churches preserved by the Churches Conservation Trust in the English Midlands

- Battlefield Heritage Park

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |