Christianity as the Roman state religion facts for kids

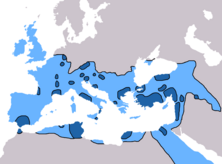

In the year 380, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. This happened when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica. This law made the type of Christianity followed by Nicene Christians the state religion. This form of Christianity believed in the Trinity, meaning God is three persons in one: the Father, the Son (Jesus), and the Holy Spirit.

Historians use different names for the church connected to the emperors, such as the Catholic Church, the Orthodox Church, or the Imperial Church. Today, the Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Catholic Church all say they are connected to this early Nicene church.

Earlier in the 4th century, after a time when Christians were persecuted, Emperor Constantine the Great called meetings of bishops. These meetings, called ecumenical councils, helped define what Christians should believe. However, Christianity still faced disagreements about important ideas, like the nature of Jesus.

In the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire began to fall apart. Invaders attacked Rome in 410 and 455. In 476, a Germanic leader named Odoacer removed the last Western Emperor. Even with these changes, the church largely stayed united, though there were tensions between the East and West.

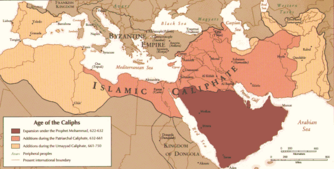

In the 6th century, Emperor Justinian I of the Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire) tried to take back parts of the Western Empire. He succeeded for a while, holding Rome until 751. This time is known as the Byzantine Papacy. Later, in the 7th to 9th centuries, early Muslim conquests spread Islam across many Christian lands, including the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Southern Italy and Spain. This greatly reduced the size of the Byzantine Empire and its church.

Justinian I, who became emperor in 527, saw the leaders (patriarchs) in Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem as the main authorities in the state-supported church. This system was called the Pentarchy. However, Justinian also believed he had the right to control church laws and beliefs.

Not all Christians were under the emperor's control. The Oriental Orthodox Churches, for example, had separated after rejecting the Council of Chalcedon in 451. In Western Europe, Christian communities followed their own rules and customs, not those of the emperor in Constantinople. Even popes from the East, loyal to the emperor as a political leader, refused to accept his authority in religious matters.

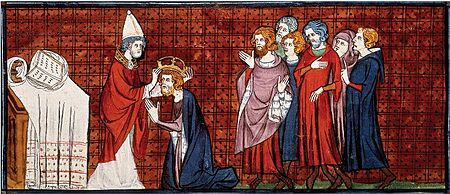

Pope Gregory III (731–741) was the last Bishop of Rome to ask the Byzantine emperor to approve his election. When Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor on December 25, 800, the political split between East and West became permanent. Spiritually, the main Christian church remained united in theory until the East–West Schism in 1054. This was when Rome and Constantinople officially separated by excommunicating each other. The Byzantine Empire finally fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

The spread of Christianity to Germanic, Pictish, and Celtic peoples, who were not part of the Roman Empire, helped create the idea of a universal church. This church was seen as separate from any single state. In the East, however, many believed that when the Roman Empire became Christian, God's perfect world order had been achieved. They thought of the church and the empire as deeply connected.

The idea of a universal church continues today in the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the Church of the East. Many other churches, like the Anglican Communion, also claim to be connected to this early universal church.

Contents

History of the Church and State

Early Christianity and the Roman Government

By the end of the 1st century, Roman officials saw Christianity as a separate religion from Judaism. This distinction became official around 98 AD under Emperor Nerva. Christians were then excused from paying a special tax that Jews had to pay.

Because Christians did not pay this tax, they had to find other ways to show loyalty to the empire. They refused to worship the Roman gods or the emperor as a god. This sometimes led to persecution and martyrdom, where Christians died for their faith. Church leaders like Tertullian tried to explain that Christians were not disloyal. They argued that Christians could pray for the emperor's well-being in their own way.

Christianity spread widely, especially in the eastern parts of the empire and beyond its borders. In the West, it was less common at first, but important Christian groups grew in cities like Rome and Carthage. By the end of the 3rd century, Christianity was the main faith in some areas. Some experts estimate that Christians made up about 10% of the Roman population by 300 AD. This number grew quickly in the 4th century, reaching over 50% by 350 AD. Many believe Christianity succeeded because it offered a hopeful message and church leaders met people's needs better than other religions.

In 301, the Kingdom of Armenia became the first nation to adopt Christianity as its state religion.

Christianity in Late Antiquity

By the end of the 4th century, the Roman Empire had split into two parts: the Western and Eastern Empires. Even so, their economies and the official church were still closely connected. The two halves had always had cultural differences. For example, people in the East mostly spoke Greek, while in the West, Latin was more common.

When Christianity became the state religion, scholars in the West had mostly stopped using Greek. Even the church in Rome, which used Greek in its services for a long time, eventually switched to Latin. Jerome's Vulgate, a Latin translation of the Bible, began to replace older Latin versions.

The 5th century saw more divisions within Christianity. Emperor Theodosius II called two church councils in Ephesus. The first one in 431 condemned the teachings of Nestorius, the Patriarch of Constantinople. Nestorius believed that Christ's divine and human natures were separate. He taught that Mary was the mother of Christ, but not the mother of God.

The second council in 449 supported the teachings of Eutyches, who believed Christ had only one nature, different from humans. The First Council of Ephesus rejected Nestorius's view. This caused churches around the city of Edessa to break away from the imperial church. Many Nestorians were persecuted and fled to Persia, joining the Church of the East.

The Second Council of Ephesus supported Eutyches, but this was overturned two years later by the Council of Chalcedon. Many Christians in Egypt and the Levant rejected the Council of Chalcedon. They preferred a different theology called miaphysitism. This led to another split, forming the churches now known as Oriental Orthodoxy. Those who supported the Council of Chalcedon were called "Melkites," meaning "imperial" or "followers of the emperor." Despite these splits, the Chalcedonian Nicene church still represented most Christians within the Roman Empire.

End of the Western Roman Empire

In the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire quickly fell apart. Germanic tribes, like the Goths and Vandals, took over the western provinces. Rome was attacked and looted in 410 and 455. In 476, the Germanic leader Odoacer conquered Italy and removed the last Western emperor, Romulus Augustus.

These Germanic tribes, who followed a different Christian belief called Arianism, set up their own churches. However, they generally allowed the local people to remain part of the imperial church.

In 533, Emperor Justinian I in Constantinople launched a military campaign to reclaim the western provinces. He started with North Africa and then moved to Italy. His success in taking back much of the western Mediterranean was short-lived. The empire soon lost most of these gains, but it held Rome until 751.

Justinian strongly believed in Caesaropapism. This meant he thought he had the right and duty to control church laws and beliefs. By the end of the 6th century, the church within the Eastern Empire was closely tied to the government. In the West, however, Christianity was mostly under the laws of nations that were not loyal to the emperor.

Church Leaders in the Empire

Emperor Justinian I gave special authority to five important church centers: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem. This system was meant to cover his entire empire. The First Council of Nicaea in 325 had already said that the bishop of a main city had some power over other bishops in the area. It also recognized the special authority of Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch, and gave special recognition to Jerusalem.

Constantinople was added at the First Council of Constantinople (381). The Council of Chalcedon (451) later placed more regions under Constantinople's authority.

Rome never fully accepted this "pentarchy" (rule by five) as the sole leadership of the church. Rome believed that only the three "Petrine" sees (Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch), which were founded by Saint Peter or his followers, had true patriarchal power.

The early Muslim conquests took over the lands of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem. This left only two major church centers: Rome and Constantinople. In 732, Emperor Leo III had disagreements with Pope Gregory III over religious images. In response, the Emperor moved territories in Greece, Illyria, Sicily, and Calabria from Rome's control to Constantinople's. This left the Bishop of Rome with very little land under the empire's control.

The Patriarch of Constantinople had already started using the title "ecumenical patriarch." This showed his view of his important position in the Christian world, which was ideally led by the emperor and the patriarch of the capital city. Over time, the idea of the emperor leading the state church led to the Patriarch of Constantinople becoming the main leader in the East.

Rise of Islam and its Impact

The Rashidun conquests began to spread Islam beyond Arabia in the 7th century. They first clashed with the Roman Empire in 634. At that time, both the Roman and Persian Empires were weakened by decades of war. By the late 8th century, the Umayyad caliphate had conquered all of Persia and much of the Byzantine territory. This included Egypt, Palestine, and Syria.

Suddenly, a large part of the Christian world was under Muslim rule. Over the next centuries, Muslim states became very powerful in the Mediterranean region.

Although the Byzantine church claimed religious authority over Christians in Egypt and the Levant, most Christians there were already part of other groups, like the Miaphysites. The new Muslim rulers often offered religious tolerance to Christians of all types. Also, people in the Muslim Empire could become Muslims simply by saying they believed in one God and respected Muhammad. As a result, many people in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria accepted their new rulers and became Muslims within a few generations. Muslim forces later found success in parts of Europe, especially Spain.

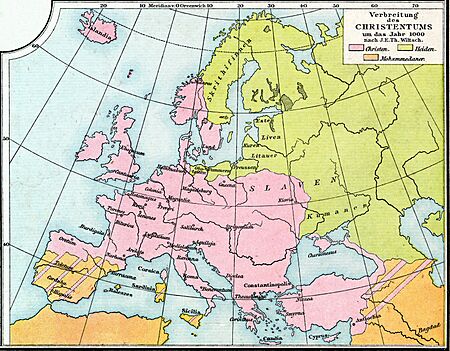

Spread of Christianity in Europe

During the 9th century, the Emperor in Constantinople encouraged missionaries to nearby nations. These included the Muslim caliphate and the Turkic Khazars. In 862, he sent Saints Cyril and Methodius to the Slavic region of Great Moravia. By then, most of the Slavic people in Bulgaria were Christian, and Tsar Boris I himself was baptized in 864. Serbia became Christian around 870. In early 867, Patriarch Photios I of Constantinople wrote that the Kievan Rus' (early Russians) had accepted Christianity. However, they were fully Christianized only at the end of the next century.

Of these new Christian areas, the Church in Great Moravia chose to connect with Rome, not Constantinople. The missionaries there sided with the Pope during a church disagreement (the Photian Schism). After important victories over the Byzantines, Bulgaria declared its church independent and made its leader a patriarch. Constantinople recognized this in 927. However, Emperor Basil II later ended this independence after conquering Bulgaria in 1018.

In Serbia, which became an independent kingdom in the early 13th century, Stephen Uroš IV Dušan made the Serbian archbishop a patriarch in 1346. This rank was kept until after the Byzantine Empire fell. No Byzantine emperor ever ruled Russian Christianity.

The spread of the church in western and northern Europe began much earlier. The Irish became Christian in the 5th century, the Franks at the end of the same century, and the English at the end of the 6th century. By the time Byzantine missions started in central and eastern Europe, Christian Western Europe was mostly independent of the Byzantine Empire. It included Germany and parts of Scandinavia.

This situation helped the idea of a universal church that was not tied to any single state. Long before the Byzantine Empire ended, Poland, Hungary, and other central European peoples were part of a church that did not see itself as the empire's church. After the East-West Schism, they even stopped being in communion with the Byzantine church.

East–West Schism (1054)

With the defeat of the last leader of Ravenna in 751, Rome was no longer part of the Byzantine Empire. The popes had to seek protection elsewhere. They turned to the Franks. When Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as emperor on December 25, 800, the political split between East and West became final.

Disagreements between the church in Rome, which claimed authority over all other churches, and the church in Constantinople, which was now the main church in the empire, eventually led to a major split. In 1054, they officially excommunicated each other.

Most European Christians broke away from Constantinople, except for those ruled by the Byzantine Empire (like the Bulgarians and Serbs) and the early Russian Church. The Russian Church became independent in 1448, just five years before the Byzantine Empire fell. After the empire's fall, the Ottoman Turks put all their Orthodox Christian subjects under the leadership of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Western Christians who set up Crusader states in Greece and the Middle East appointed their own Latin (Western) church leaders. This made the split even more real and lasting. Attempts were made in 1274 and 1439 to reunite the East and West. However, the agreements reached were rejected by most Byzantine Christians.

In the East, the idea that the Byzantine emperor was the head of all Christians continued as long as the empire existed, even when its territory became very small. In 1393, just 60 years before Constantinople fell, Patriarch Antony IV of Constantinople wrote that it was not possible for Christians to have a Church without an emperor. He said the empire and the Church were deeply united and could not be separated.

Legacy of the Church

After the split between the Eastern and Western churches, some emperors tried to reunite Christianity. They hoped to get help from the pope and Western Europe against the Muslims who were taking over the empire's land. However, the time of the Western Crusades against Muslims had already passed.

Even when persecuted by the emperor, the Eastern Church, as one historian said, "counted the days until they should be rid not of their emperor... but of their current misfortunes." The church and the empire had become so connected in the minds of Eastern bishops that they found it hard to imagine Christianity without an emperor.

In Western Europe, however, the idea of a universal church linked to the Emperor of Constantinople was replaced. Instead, the church in Rome became supreme. Being part of a universal church replaced being a citizen of a universal empire. A new society centered on Christianity formed across Europe.

The Western Church began to emphasize the term Catholic to show its worldwide reach. The Eastern Church emphasized Orthodox to show it held the true teachings of Jesus. Both churches claim to be the direct continuation of the early united state-approved church. Many churches that came from the Protestant Reformation, like Lutheranism and Anglicanism, also keep the core beliefs of this early church.

See also

- Caesaropapism

- Chalcedonian Christianity

- Christian state

- Early Christianity

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- History of Oriental Orthodoxy

- History of Roman Catholicism

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |