History of the Eastern Orthodox Church facts for kids

The history of the Eastern Orthodox Church tells the story of how this Christian church came to be, what happened over time, and how it changed. Eastern Orthodox Christians believe their church started with Jesus Christ and his Apostles. These Apostles chose leaders called bishops, and these bishops then chose others, in a process known as Apostolic Succession. This means they believe their leaders are directly connected to the first Apostles.

Over time, five main centers of Christianity, called Patriarchates, were set up to organize the Christian world. Four of these ancient centers are still part of the Orthodox Church today. The Eastern Orthodox Church became what it is now during a period called late antiquity (from the 3rd to the 8th century). This was when important meetings called Ecumenical Councils took place, disagreements about beliefs were settled, important church leaders called Fathers of the Church wrote their teachings, and Orthodox ways of worship, like the special services (liturgies) and main holidays, became fixed.

In the early medieval period, Orthodox missionaries traveled north to share Christianity with people like the Bulgarians, Serbs, and Russians. At the same time, the Eastern Patriarchates and the Latin Church in Rome slowly grew apart. This led to the Great Schism in the 11th century, when Orthodoxy and the Latin Church (which later became the Roman Catholic Church) officially separated. Later, the Fall of Constantinople meant that many Orthodox Christians came under the rule of the Ottoman Turks. But Orthodoxy still grew strong in Russia and among Christian groups within the Ottoman Empire. As the Ottoman Empire became weaker in the 1800s, several Orthodox nations became independent and formed their own autocephalous (self-governing) Orthodox churches in Southern and Eastern Europe.

Today, the Russian and Romanian Orthodox churches have the most followers. The oldest Eastern Orthodox communities still around are the churches of Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Georgia.

Contents

Early Christian Communities

Apostolic Beginnings

Christianity first spread in the eastern part of the Roman Empire, where most people spoke Greek. The Apostles traveled widely, starting Christian groups in big cities. The first community appeared in Jerusalem, then in places like Antioch and Ethiopia. Other important early centers were Rome and Greece, as well as Byzantium (which later became Constantinople).

Orthodox Christians believe in apostolic succession, meaning their bishops are direct successors of the Apostles. This was very important for these early groups, as they saw themselves as keeping the original Christian teachings alive. The word "church" (ekklesia in Greek) didn't mean a building back then. It meant a community or gathering of people. Early Christians believed that a church was formed when people gathered for the Eucharist, led by a Bishop. As St. Ignatius of Antioch said, "Don't do anything connected with the Church without the bishop."

The original Christian communities in the East before the Great Schism included:

- the Greek churches started by Saint Paul.

- the Antiochian and Asia Minor churches started by Saint Peter.

- the Coptic (Egyptian) churches started by Saint Mark.

- the Syriac churches in Mesopotamia.

- the Georgian church, traditionally started by Saint Andrew and Saint Nino.

- the Armenian church, traditionally started by Saint Jude and Saint Bartholomew.

- the church of Jerusalem, started by Saint James, which includes churches in Samaria and Judea (the Holy Land).

The church in Rome is traditionally believed to have been founded by both Saint Peter and Saint Paul.

Early Christians faced persecution, so they often met in secret. The first legal churches were built in Armenia, which became the first country to make Christianity its official state religion around 301 AD. Before Christianity was legal, some churches met in catacombs (underground tunnels) in Europe and in underground cities in Anatolia.

Church Fathers and Teachings

Important church leaders, called Church Fathers, helped organize the church and clarify its teachings. Their writings are known as Patristics. This tradition of clarifying beliefs continued through the Ecumenical Councils once Christianity became legal.

The Bible for Christians began with the accepted books of the Koine Greek Old Testament, called the Septuagint. This is still the Old Testament for Orthodox Christians. The New Testament includes the Gospels, Revelation, and letters from the Apostles. The earliest New Testament texts were written in Koine Greek.

Early Christians didn't have copies of the Bible easily available. So, church services, especially the liturgy, helped people learn these sacred texts. Orthodox services still teach people today. Collecting and confirming all the different Christian writings into an official Bible was a long process, often driven by the need to correct false teachings.

Divine Liturgy

Christian worship services, especially the Eucharist, are based on Jesus's actions and words at the Last Supper ("do this in remembrance of me"). They use bread and wine and repeat his words. The rest of the worship service has roots in Jewish traditions like Passover, Siddur, and synagogue services, including singing hymns (especially the Psalms) and reading from the Old and New Testament. The way services are done became more uniform after the church decided on the Biblical canon, following guidelines like the Apostolic Constitutions.

The Bible in Orthodoxy

For Orthodox Christians, the Bible contains texts approved by the church to share the most important parts of what it already believed. The oldest list of Bible books is the Muratorian fragment from around 170 AD. The oldest complete Christian Bible was found at Saint Catherine's Monastery (the Codex Sinaiticus). These texts were not fully accepted as official until the church reviewed and approved them in 368 AD. Orthodox Christians believe that salvation comes not just from knowing scripture, but from being part of the church community and growing closer to God through its practices.

The Pentarchy

By the 5th century, Christian church organization had settled into a system of five main centers, called "pentarchy" or five sees (patriarchates). The first four were in the largest cities of the Roman Empire, and the fifth was in Jerusalem, which was important because Christianity began there, even though it was a smaller city. All five places also had Christian communities that traced their beginnings back to one or more Apostles.

In order of importance, the five patriarchates were:

- Rome (founded by Sts. Peter and Paul), now in Italy. This was the only one in the Western Roman Empire and is now known as the seat of the Pope of the Roman Catholic Church.

- Constantinople (St. Andrew), now Istanbul in Turkey.

- Alexandria (St. Mark), now in Egypt.

- Antioch (St. Peter), now in Syria.

- Jerusalem (St. James), now in Israel.

Saint Peter is said to have founded both the churches of Rome and Antioch. The Eastern churches recognize Antioch as the church founded by St. Peter.

The Byzantine Period

When Emperor Constantine the Great established the Eastern Roman Empire, Christianity became a legal religion in 313 AD. This stopped the widespread Roman persecution of Christians. Christianity became the official state religion in the Eastern Roman Empire when Theodosius I called the Second Ecumenical Council in Constantinople in 381 AD. This council ended the Arianism controversy by confirming the belief in the Trinity.

Legalizing Christianity meant that Ecumenical Councils could be held to solve disagreements and set down official church beliefs, called dogma. These councils helped define what it meant to be a Christian in a universal sense (the Greek word for universal is katholikós, or catholic). According to some historians, "Byzantine culture and Orthodoxy are one and the same."

In the 530s, the second Church of the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) was built in Constantinople under Emperor Justinian I. It became a very important church for the rulers of the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as Byzantium.

Ecumenical Councils

The tradition of church councils began with the Council of Jerusalem around 50 AD, though this is not counted as an Ecumenical Council.

The First seven Ecumenical Councils were held between 325 AD (the First Council of Nicaea) and 787 AD (the Second Council of Nicaea). Orthodox Christians see these councils as the final and most important interpretations of Christian beliefs.

- First Council of Nicaea (Nicaea, 325): Called by Emperor Constantine, it condemned the idea of Arius that Jesus was a created being, not truly God.

- Second Ecumenical Council (Constantinople, 381): Defined the nature of the Holy Spirit, stating He is equal to the Father and the Son. This council ended the Arian conflict in the East.

- Third Ecumenical Council (Ephesus, 431): Affirmed that Mary is truly the "Birth-giver" or "Mother" of God (Theotokos), against the teachings of Nestorius.

- Fourth Ecumenical Council (Chalcedon, 451): Affirmed that Jesus is truly God and truly man, with two natures that are not mixed, against Monophysite teaching.

- Fifth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople, 553): Further explained the relationship between Jesus's two natures.

- Sixth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople, 681): Declared that Christ has two wills, human and divine, matching his two natures, against Monothelite teachings.

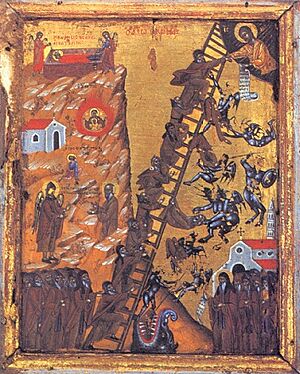

- Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicea, 787): Called by Empress Irene, it confirmed that making and honoring icons (religious images) is good, but worshipping them is forbidden. It also forbade three-dimensional statues.

The Orthodox Church also recognizes the Fourth Council of Constantinople in 879 as Ecumenical.

Fighting Arianism

The First Ecumenical Council dealt with the teachings of Arius, a priest from Alexandria. Arius taught that Jesus Christ was created by God, and not God in the same way as the Father. This council declared that Jesus Christ was distinct from God in existence (a different hypostasis or person), but was God in essence, being, and nature (the same ousia or substance).

The conflict didn't end there. Later, two emperors, Constantius II and Valens, supported Arianism. It wasn't until Emperors Gratian and Theodosius that Arianism was mostly removed from the ruling class in the East.

Iconoclasm

The Iconoclasm movement (730–787 and 813–843) was a time when some in the Byzantine church believed that religious images (icons) were wrong and should be destroyed. They thought icons were like "graven images" forbidden in the Bible. This led to the destruction of much Christian art. However, the Seventh Ecumenical Council later declared Iconoclasm to be a false teaching. The Orthodox Church understands the biblical ban on "graven images" as a ban on worshipping idols, not on creating religious art to honor God and the saints.

Growing Apart from Rome

After the Council of Chalcedon (451), the Patriarchate of Alexandria separated from the Byzantine Church. Then, the Muslim conquests of Palestine and Syria led to the fall of the Patriarchates of Antioch and Jerusalem. These events meant that the idea of a "pentarchy" (five main centers) became more of a theory than a reality. The Patriarch of Constantinople gained more power, acting as the main Patriarch in the East until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

Two main issues caused tension between the East and West: the role of the bishop of Rome (the Pope) and the addition of the Filioque clause to the Nicene Creed. These differences were first openly discussed during the time of Patriarch Photius I.

Rome believed its Pope had supreme authority over the whole Church, a God-given right. Many Eastern churches believed the Roman See had a primacy of honor, meaning the Pope was "first among equals," but not an absolute ruler who could make infallible statements alone.

The Photian Schism

Photius did not accept the Pope's supreme authority in Orthodox matters. He also rejected the Filioque clause, which the Latin church had added to the Nicene Creed. This clause became a major point of disagreement leading to the Great Schism. The argument also involved who had authority over the church in Bulgaria.

Converting Slavs

In the 9th and 10th centuries, Christianity spread widely in Eastern Europe, first in Bulgaria and Serbia, then in Kievan Rus'. For a while, it seemed possible that all the newly baptized South Slav nations (Bulgarians, Serbs, and Croats) might join the Western church, but in the end, only the Croats did.

The Serbs were baptized around the 7th century. The official establishment of Christianity as the state religion for Serbs happened during the time of the Orthodox missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius in the 9th century. The Serbs and Bulgarians adopted the Old Slavonic language for their church services instead of Greek.

In 863, missionaries from Constantinople converted King Boris I of Bulgaria. Boris realized that using the Greek language in church services might increase Byzantine influence in Bulgaria. So, he asked Constantinople for an independent Bulgarian Church, but they refused. Boris then turned to the Pope. This led to a conflict between Rome and Constantinople over Bulgaria. Eventually, Bulgaria returned to the Byzantine rite and gained an autonomous (self-governing) national Archbishopric. In 893 AD, Bulgaria made Slavonic the official language of its Church and State.

The Great Schism

In the 11th century, the East–West Schism occurred between Rome and Constantinople. This led to the separation of the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church. Doctrinal issues, like the filioque clause and the Pope's authority, were involved. These were made worse by cultural and language differences between Latin-speaking Westerners and Greek-speaking Easterners. Before this, the Eastern and Western parts of the Church had often disagreed, especially during the times of iconoclasm and the Photian schism.

Orthodox Byzantine Greeks felt that the Papacy was acting too much like a monarchy, which they believed was not in line with the Church's history. Archbishop Niketas of Nicomedia wrote in the 12th century that while they recognized Rome's honor, they could not accept decrees made without their input, as that would make them "slaves, not sons."

Eastern Monastic Tradition

When Christianity became a legal religion in the Roman Empire under Constantine the Great (313 AD), many Orthodox Christians felt that the moral life of Christians was declining. In response, many chose to leave society and become monks. Monasticism grew quickly, especially in Egypt. Monks like St. Anthony the Great lived alone or in small groups, gathering for worship only on Saturdays and Sundays. This was not a new idea, but it became a widespread movement at this time. Later, monastic life developed in places like Mount Athos in Greece and Cappadocia in Syria, with different forms of monastic organization.

The Crusades

A major break between Greeks and Latins happened after the Fourth Crusade captured and sacked Constantinople in 1204. This was not the only time Roman Catholic crusaders attacked Orthodox Christians. The sacking of Constantinople, including the Church of Holy Wisdom, and the establishment of the Latin Empire in Constantinople and other parts of Greece are seen as very important events. Many Orthodox churches were turned into Roman Catholic properties. This is still remembered with sadness today.

The Teutonic Knights also tried to conquer Orthodox Russia, an effort supported by Pope Gregory IX. A major defeat for them was the Battle of the Ice in 1242. Sweden also launched several crusades against Orthodox Novgorod. Many Orthodox Christians believe that the actions of the Catholics in the Mediterranean weakened the Byzantine Empire, leading to its eventual fall to Islam.

In 2004, Pope John Paul II formally apologized for the sacking of Constantinople in 1204, and Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople accepted the apology. Many holy items and treasures stolen during this time are still held in Western European cities, especially Venice.

The Latin Empire in the East

After the Sack of Constantinople in 1204 AD by Roman Catholic Crusaders, much of Asia Minor came under Roman Catholic rule, and the Latin Empire of the East was established. Various European kingdoms were set up. After Constantinople fell to the Latin West, the Empire of Nicaea was formed. This empire later defeated the Latin forces and re-established Orthodox rule in Constantinople and Asia Minor.

The Ottoman Period

In 1453 AD, Constantinople, the last major city of the Byzantine Empire, fell to the Ottoman Empire. By this time, Egypt had been under Muslim control for about 700 years. Jerusalem had been conquered by Muslims in 638, briefly won back by Rome in 1099, and then reconquered by the Ottoman Muslims in 1517.

Under Ottoman rule, the Greek Orthodox Church gained power as an autonomous millet (a self-governing community). The Ecumenical Patriarch became the religious and administrative leader of all Orthodox people in the Empire, though ethnic Greeks mostly dominated this system.

Violence against non-Muslims was common under the Ottoman Empire. Many individual Christians became martyrs for their faith.

Religious Rights

The Orthodox Church was an accepted institution under the Ottomans, unlike Catholicism, which was seen as connected to enemy states. The Orthodox Church actually grew in size during Ottoman rule, including the building of churches and monasteries.

Fall of the Ottoman Empire

The decline of the Ottoman Empire was partly triggered by a dispute between Roman Catholics and Orthodox Christians over who controlled the Church of the Nativity and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. In the 1850s, the Ottoman Sultan sided with the French (Catholic side), which angered the local Orthodox monks. This decision led to the Crimean War in 1853 between Russia and the Ottoman Empire.

Persecution by the "Young Turks"

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there were systematic massacres of Christians in the Ottoman Empire. This included the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian genocides. As a result, the number of Orthodox Christians in the Anatolian peninsula sharply declined.

Republic of Turkey

During the Lausanne Conference in 1923, Turkey and Greece agreed to a population exchange. Muslims in Greece (except in Eastern Thrace) were sent to Turkey, and Greek Orthodox people in Turkey (except in Istanbul) were sent to Greece.

In September 1955, a pogrom (violent riot) targeted Istanbul's Greek minority. In 1971, the Halki seminary in Istanbul, an important Orthodox theological school, was closed.

Orthodoxy in Other Muslim-Majority States

Orthodox communities continue to exist in various Muslim-majority countries, including those under the Palestinian National Authority and in countries like Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria, Iran, and others.

Jerusalem

The Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem and the leaders of the Orthodox Church are based in the ancient Church of the Holy Sepulchre, built in 335 AD.

Orthodoxy in Russia

The conversion of the Bulgarians helped lead to the conversion of the East Slavs. By the early 11th century, most of the Slavic world, including Bulgaria, Serbia, and Russia, had become Orthodox Christian. Bulgaria's Church was recognized as a Patriarchate in 927, Serbia's in 1346, and Russia's in 1589.

Russia also became a protector of Orthodoxy through a series of wars with the Muslim world.

Under Mongol Rule

Russia was under Mongol rule from the 13th to the 15th century. This period, known as the Tatar period, caused great hardship for Russia. Much of Russia was controlled by Mongols, and Russian princes were under their authority.

The end of the Golden Horde's rule is often linked to the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380, which includes the story of the Russian monk and warrior Alexander Peresvet. The final event that formally ended Mongol rule in Russia was the Great Stand on the Ugra River in 1480.

Synodal Period

The Russian Orthodox Church had a special position in the Russian Empire. It was exempt from taxes in 1270 and could tax peasants. However, in 1721, Peter I placed the Church under the control of the Tsar. He replaced the Russian Patriarchate with the Most Holy Synod, which was run by an official appointed by the Tsar.

The Church, like the Tsarist state, was seen as an enemy by the Bolsheviks and other Russian revolutionaries.

Under the Soviet Union

After the October Revolution in 1917, the Soviet Union aimed to unite people under Communist rule. This included Eastern European and Balkan states. Since some Slavic groups connected their heritage to their churches, both the people and their churches were targeted by the Soviets, who promoted state atheism. While officially allowing "religious freedom," the state declared atheism as the only scientific truth, and criticizing atheism was forbidden.

It is estimated that millions of Christians died or were imprisoned in gulags (labor camps). Orthodox priests and believers faced executions, imprisonment, and forced labor. This state-sponsored atheism turned the Church into a persecuted one. In the first five years after the Bolshevik revolution, many bishops and priests were executed.

Between 1927 and 1940, the number of Orthodox churches in Russia dropped dramatically. Many Orthodox priests were arrested. The widespread persecution and internal disagreements meant the seat of the Patriarch of Moscow was empty from 1925 to 1943.

In the Soviet Union, churches were systematically closed and destroyed. The charitable and social work previously done by the Church was taken over by the state. Church property was confiscated. This persecution continued even after Stalin's death until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Since then, the Russian Orthodox Church has recognized many new martyrs as saints.

Modern History

The various self-governing (autocephalous) and autonomous churches of the Eastern Orthodox Church have their own administrations and local cultures. However, they are mostly in full communion with each other, meaning they recognize and share sacraments. One exception was the lack of relations between the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR) and the Moscow Patriarchate (the main Orthodox Church of Russia) from the 1920s, due to the latter being under the Soviet regime. However, these two branches reunited on May 17, 2007. There are also some tensions between those who use the "New Calendar" and those who use the "Old Calendar" for church feasts.

See also

- Christian Church

- Church Fathers

- History of Christianity

- History of Eastern Christianity

- Pentarchy

- Seven Ecumenical Councils

- Eastern Orthodoxy in Greece

- Eastern Orthodoxy in North America

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |