History of Christianity facts for kids

Christianity is a religion based on the life, teachings, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. It began in the 1st century AD, after Jesus died. It started as a small group of Jewish people in Judea. But it quickly spread across the Roman Empire. Even though early Christians faced persecution, Christianity later became the official religion of the Roman Empire.

In the Middle Ages, Christianity spread into Northern Europe and Russia. During the Age of Exploration, it expanded worldwide. Today, Christianity is the largest religion in the world.

Over time, the Christian religion faced disagreements and splits. These led to four main branches: the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox churches, Oriental Orthodoxy, and Protestant churches.

Most of the first Christians were Jewish or people who had converted to Judaism. A challenge came when non-Jewish people wanted to become Christians. The question was whether they needed to become Jewish first. St. Peter decided they did not. This was further discussed at the Council of Jerusalem.

The teachings of the apostles sometimes caused problems with Jewish religious leaders. This led to the death of Stephen and James the Great. Christians were also expelled from synagogues. This helped Christianity become a separate religion from Judaism. The name "Christian" was first used for Jesus's followers in Antioch.

Contents

- Early Christian Beliefs

- Connecting with Jewish Traditions

- The Church After the Apostles

- Christianity Becomes Legal

- The Church in the Early Middle Ages (476 – 800)

- The Church in the High Middle Ages (800 – 1499)

- The Church and the Renaissance (1399 – 1599)

- The Protestant Reformation (1521 – 1579)

- The Counter-Reformation

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Christian Beliefs

We learn about the beliefs of the first Christians from the Gospels and the Epistles in the New Testament. The earliest writings mention Christian beliefs, hymns, and stories about Jesus's death, empty tomb, and appearances after his resurrection. These texts were likely written soon after Jesus's crucifixion.

Connecting with Jewish Traditions

Christianity kept many practices from Jewish traditions. Christians believed the Jewish scriptures were holy. They used the Septuagint (a Greek translation of the Old Testament) and added new texts called the New Testament. Christians believed Jesus was the God of Israel who took human form. They saw him as the Messiah (or Christ) that the Old Testament had predicted.

Christianity continued many Jewish practices. These included worship services with incense and an altar. They also used scripture readings similar to synagogue practices. Sacred music, hymns, and prayer were also important. They followed a religious calendar and had only male priests. Practices like fasting were also continued.

The Church After the Apostles

After most of the apostles died, bishops took over leading Christian communities. This time is called the post-apostolic period. It includes the time when Christians were persecuted. This period ended when Christian worship became legal under Constantine the Great. The word Christianity was first used around 107 AD by Ignatius of Antioch.

Facing Persecution

Early Christians often faced persecution. This sometimes meant death. Early martyrs included Stephen and James, son of Zebedee. Widespread persecutions by the Roman Empire began in 64 AD. Emperor Nero blamed Christians for the Great Fire of Rome.

Church tradition says that Peter and Paul died as martyrs in Rome during Nero's persecution. Many New Testament writings mention these difficult times. For about 250 years, Christians suffered because they refused to worship the Roman emperor. This was seen as treason and punished by execution. Despite this, Christianity continued to spread across the Mediterranean region. By the late fourth century, it became the main religion in the Roman Empire.

Christianity Becomes Legal

In 311 AD, Galerius issued a law allowing Christians to practice their religion. In 313 AD, Constantine I and Licinius announced religious tolerance for Christians in the Edict of Milan. Constantine became the first Christian emperor. He learned about Christianity from his mother, Helena.

By 391 AD, under Emperor Theodosius I, Christianity became the official state religion of Rome. When Christianity was legalized, the Church adopted the same administrative areas as the government, calling them dioceses. The Bishop of Rome claimed to be the most important and took the title of pope.

During this time, several important meetings called Ecumenical Councils took place. These councils mainly discussed beliefs about Jesus Christ. The Councils of Nicea (324, 382) condemned Arianism (a belief about Jesus's nature) and created the Nicene Creed to define Christian faith. The Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorianism and affirmed that the Blessed Virgin Mary was Theotokos ("Mother of God"). The Council of Chalcedon was very important. It stated that Christ has two natures: fully God and fully human at the same time. This condemned Monophysitism (a belief that Christ had only one nature).

The Church in the Early Middle Ages (476 – 800)

The Church in the Early Middle Ages saw a big change in the Roman world. With the Muslim invasions in the seventh century, the Western (Latin) and Eastern (Greek) parts of Christianity grew more distinct. The Bishops of Rome became more focused on barbarian kings than on the Byzantine Emperors. This led to Pope Leo III crowning Charlemagne as "Emperor of the Romans" in Rome on Christmas Day, 800 AD.

The Pope's Role in the Early Middle Ages

The city of Rome was greatly affected by wars in Italy during the Early Middle Ages. After the Lombards invaded, Rome had to defend itself. The popes, out of necessity, started feeding the city, negotiating treaties, and even hiring soldiers. Because the Empire failed to send help, the popes looked for support from other sources, especially the Franks.

The Church in the High Middle Ages (800 – 1499)

The High Middle Ages lasted from Charlemagne's crowning in 800 AD to the end of the fifteenth century. This period saw the fall of Constantinople (1453), the end of the Hundred Years' War (1453), and the discovery of the New World (1492). It was followed by the Protestant Reformation (1515).

The Crusades

The Crusades were military campaigns by Christian knights. Their goal was to defend Christians and expand Christian lands. Most crusades were in the Holy Land against Muslim forces, supported by the Pope. There were also crusades against Islamic forces in southern Spain and Italy. Teutonic knights also fought against pagan groups in Eastern Europe. Some crusades were even against other Christian groups seen as heretics.

The Holy Land was part of the Roman Empire until Islamic conquests in the seventh and eighth centuries. Christians were generally allowed to visit holy places there until 1071. That year, the Seljuk Turks stopped Christian pilgrimages and attacked the Byzantines. Emperor Alexius I asked Pope Urban II for help. Instead of sending money, Urban II called upon Christian knights at the Council of Clermont in 1095. He combined the idea of pilgrimage with fighting a holy war.

The East-West Schism

The East-West Schism, also called the Great Schism, divided the Church into Western (Latin) and Eastern (Greek) branches. These became Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. This was the first major split since some Eastern groups rejected the Council of Chalcedon's decisions. The schism is usually dated to 1054. It resulted from a long period of disagreement between Latin and Greek Christians over the Pope's authority and certain beliefs like the filioque. Cultural and language differences made feelings worse.

The split became "official" in 1054. The Pope's representatives told Patriarch Michael Cerularius of Constantinople that he was excommunicated. A few days later, he excommunicated them. Attempts to reunite were made in 1274 and 1439. But in both cases, the Eastern leaders who agreed were rejected by most Orthodox Christians. However, some Eastern churches did reunite with the West, forming the "Eastern Rite Catholic Churches". More recently, in 1965, the Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople lifted the mutual excommunications. But the split still remains.

Both groups come from the Early Church. Both recognize each other's bishops as having apostolic succession. They also recognize each other's sacraments as valid. Both acknowledge the Bishop of Rome's importance. But Eastern Orthodoxy sees this as a special honor, with limited power in other dioceses.

The Western Schism

The Western Schism, or Papal Schism, was a long crisis in Western Christianity from 1378 to 1416. During this time, there were two or more people claiming to be the true Pope. This made it hard to know who the real Pope was. This conflict was about politics, not about religious beliefs.

The Church and the Renaissance (1399 – 1599)

The Renaissance was a time of great cultural change and artistic achievement. In Italy, it brought a focus on classical ideas and more wealth from trade. The city of Rome, the Papacy, and the Papal States were all affected. It was a time of amazing art and architecture. The Church supported artists like Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, Bramante, Raphael, and da Vinci. However, wealthy Italian families often helped their members become bishops or even popes. Some of these leaders, like Alexander VI, were known for bad behavior.

The Protestant Reformation (1521 – 1579)

In the early 16th century, two theologians, Martin Luther and Ulrich Zwingli, started movements to reform the Church. Unlike earlier reformers, they believed the problems were in the Church's teachings, not just its morals. They wanted to change current doctrines to fit their idea of the "true gospel". The Protestant Reformation is called this because its leaders "protested" against the Church's leaders and the pope. They chose to make their changes separately. The term "Protestant" was not used by these leaders at first. They called themselves "evangelical," meaning they wanted to return to the "true gospel."

The Protestant Reformation usually started with Martin Luther and his 95 Theses in 1517 in Wittenberg, Germany. Early protests were against practices like simony (selling church offices) and the sale of indulgences (pardons for sins). The Protestant view eventually included new ideas like sola scriptura (scripture alone) and sola fide (faith alone). The three most important traditions that came from the Protestant Reformation were Lutheran, Reformed (like Calvinist and Presbyterian), and Anglican.

The Protestant Reformation had two main movements: the Magisterial Reformation and the Radical Reformation. The Magisterial Reformation involved church teachers like Luther and John Calvin working with secular rulers to reform Christianity. Radical Reformers formed communities outside state control. They often made more extreme changes to beliefs, like rejecting parts of the Nicene Creed and Council of Chalcedon. The conflict between magisterial and radical reformers was often as harsh as the conflict between Catholics and Protestants.

The Protestant Reformation spread mostly in Northern Europe. But it did not take hold everywhere, like in Ireland and parts of Germany. The magisterial reformers were much more successful. The Catholic Church's response to the Protestant Reformation is called the Counter-Reformation, or Catholic Reformation. This led to a stronger belief in traditional doctrines. New religious orders were formed to improve morals and start new missionary work. The Counter-Reformation brought about 33% of Northern Europe back to Catholicism. It also started missions in South and Central America, Africa, Asia, and even China and Japan. Protestant expansion outside Europe happened on a smaller scale through colonization of North America and parts of Africa.

Martin Luther's Role

Martin Luther was a monk and a professor at the University of Wittenberg. In 1517, he published his 95 Theses. These were points to be debated about the wrongness of selling indulgences. Luther did not like the philosophy of Aristotle. As he developed his own theology, he often disagreed with other scholars.

Soon, Luther began to develop his idea of justification. This is the process by which a person is "made right" in God's eyes. In Catholic teaching, one becomes righteous by receiving God's grace through faith and doing good works. Luther's idea of justification was different. He said justification meant God "declaring someone to be righteous." God gives Christ's goodness to a person who does not have it on their own. In this view, good works are not essential and do not add to one's righteousness. Luther's disagreements with leading theologians led him to reject the authority of the Church's leaders. In 1520, he was condemned for heresy by a papal order called Exsurge Domine. He publicly burned this order and books of church law.

John Calvin's Influence

John Calvin was a French church leader and lawyer who became a Protestant reformer. He was famous for publishing Institutes of the Christian Religion in 1536. He became a leader of the Reformed church in Geneva, which became an important center for Reformed Christianity. He had great influence in the city and over its council. Some even called him a "Protestant pope."

Calvin set up a system with elders and a "consistory." Pastors and elders managed religious discipline for the people of Geneva. Calvin's theology is best known for his idea of (double) predestination. This belief held that God had decided from the beginning of time who would be saved (the elect) and who would be condemned (the reprobate). While predestination was not the main idea in Calvin's own writings, it became very important for many of his followers.

The English Reformation

Unlike other reform movements, the English Reformation started because of royal influence. Henry VIII saw himself as a very Catholic King. In 1521, he defended the Pope against Luther in a book. For this, Pope Leo X gave him the title Fidei Defensor (Defender of the Faith). However, the king later disagreed with the Pope. He wanted to cancel his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. He needed the Pope's approval for this. Catherine was the aunt of Emperor Charles V, the Pope's most important supporter. This dispute eventually led to England breaking away from Rome. The King of England was declared the head of the English (Anglican) Church. England then went through many changes, some more radical and some more traditional. This happened under rulers like Edward VI and Elizabeth I, and church leaders like Thomas Cranmer. What emerged was a state church that saw itself as both "Reformed" and "Catholic" but not "Roman." Other unofficial movements, like the Puritans, also emerged.

The Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation, or Catholic Reformation, was the Catholic Church's response to the Protestant Reformation. It involved a renewed belief in traditional practices. It also upheld Catholic teachings as the way to reform the Church and stop Protestantism from spreading. This led to the founding of new religious orders, like the Jesuits. Seminaries were established to properly train priests. There was also renewed missionary activity worldwide. New forms of spirituality developed, like those of the Spanish mystics. The whole process was led by the Council of Trent. This council clarified and restated Catholic doctrine. It issued clear definitions of beliefs and produced the Roman Catechism.

While Ireland, Spain, and France were important, the heart of the Counter-Reformation was Italy and its popes. They created the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (a list of forbidden books) and the Roman Inquisition. This was a system of courts that prosecuted heresy and related offenses. The time of St. Pius V (1566-1572) was known for stopping heresy and abuses within the Church. It also focused on improving people's religious devotion to counter Protestantism. Pius began his time as Pope by giving much money to the poor, to charity, and to hospitals. He was known for comforting the poor and sick and supporting missionaries. These popes' actions happened at the same time as the rediscovery of ancient Christian catacombs in Rome. As Diarmaid MacCulloch noted, these ancient martyrs inspired many Catholics to action and heroism.

Great Awakenings

The First Great Awakening was a wave of religious excitement among Protestants in the American colonies around 1730-1740. It focused on traditional Reformed values like strong preaching, simple worship, and a deep feeling of personal guilt and redemption through Jesus Christ. Historian Sydney E. Ahlstrom saw it as part of a "great international Protestant upheaval." This also created Pietism in Germany and Methodism in England. It aimed to revive the spirituality of existing churches. It mostly affected Congregational, Presbyterian, Dutch Reformed, German Reformed, Baptist, and Methodist churches. It also spread among enslaved people.

The Second Great Awakening (1800–1830s) focused on people who were not in churches. It aimed to give them a deep sense of personal salvation through revival meetings. It also started groups like the Mormons and the Holiness movement. The Third Great Awakening began in 1857 and spread the movement worldwide, especially in English-speaking countries. The last group to come from the "great awakenings" in North America was Pentecostalism. It started in 1906 in Los Angeles and later led to the Charismatic movement.

Restorationism

Restorationism refers to different movements that believed current Christianity had strayed from the true, original Christianity. These groups tried to "reconstruct" it, often using the Book of Acts as a guide. Restorationism grew out of the Second Great Awakening and is linked to the Protestant Reformation. However, Restorationists usually do not see themselves as "reforming" a church that has always existed. Instead, they believe they are restoring the Church that they think was lost at some point. The name Restoration is also used for the Latter-day Saints (Mormons) and the Jehovah's Witness Movement.

Christianity and Fascism

Fascism describes certain political systems in 20th-century Europe, especially Nazi Germany. When the Italian government closed Catholic youth groups, Pope Pius XI issued a letter called Non Abbiamo Bisogno. He said that Fascist governments had hidden "pagan intentions." He also stated that Catholic beliefs were not compatible with Fascism, which put the nation above God and basic human rights. He later signed agreements with the new rulers of Italy and Germany.

Many Catholic priests and monks were persecuted under the Nazi regime. This included Maximilian Kolbe and Edith Stein (Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross), who died in concentration camps. Many Catholic laypeople and clergy also helped hide Jews during the Holocaust, including Pope Pius XII. Various events, like helping downed Allied airmen, almost caused Nazi Germany to invade the Vatican before Rome was liberated in 1944.

The relationship between Nazism and Protestantism, especially the German Lutheran Church, is complex. Most Protestant church leaders in Germany said little about the Nazis' growing anti-Jewish actions. However, some, like Dietrich Bonhoeffer (a Lutheran pastor), strongly opposed the Nazis. Bonhoeffer was later found guilty of plotting to assassinate Hitler and was executed.

Fundamentalism

Fundamentalist Christianity is a movement that began mainly within British and American Protestantism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a reaction to modernism and some liberal Protestant groups that denied core Christian beliefs but still called themselves "Christian." Fundamentalism aimed to reestablish beliefs that were considered essential to being Christian. These "fundamentals" included: the Bible as God's word and the only source of authority, the virgin birth of Christ, the idea of atonement through Jesus, Jesus's bodily resurrection, and the belief that Christ would return soon.

Ecumenism

Ecumenism generally refers to movements among Christian groups to achieve some level of unity through discussion. The word "Ecumenism" comes from the Greek word oikoumene, meaning "the inhabited world," or more broadly, "universal oneness." This movement can be divided into Catholic and Protestant efforts. Protestant ecumenism often involves a new understanding of "denominationalism," which the Catholic Church does not accept.

Regarding the Greek Orthodox Church, steady progress has been made to heal the East-West Schism. In 1894, Pope Leo XIII published a letter called Orientalium Dignitas (On the Churches of the East). This letter protected the importance of Eastern traditions for the whole Church. In 1965, Pope Paul VI and Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I issued a joint declaration. This lifted the mutual excommunications from 1054.

For Catholic relations with Protestant communities, special groups were formed to encourage discussion. Documents have been created to find points of shared belief. An example is the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, produced with the Lutheran World Federation in 1999.

Ecumenical movements within Protestantism have focused on identifying core beliefs and practices essential to being Christian. This allows them to grant a more or less equal status to all groups that meet these basic criteria. One's own group might still be seen as "first among equals." This process involved redefining the idea of "the Church." This new understanding, called denominationalism, argues that each group (that meets the essential Christian criteria) is a part of a larger "Christian Church." This "Christian Church" is an abstract idea with no single physical representation. In other words, no single group claims to be "the Church." This idea is different from other groups that do consider themselves to be "the Church." Also, because the "essential criteria" usually include belief in the Holy Trinity, this has caused conflict. Non-Trinitarian groups like Latter-day Saints (Mormons) and Jehovah's Witnesses are often not seen as Christian by these ecumenical groups.

Images for kids

-

Funerary stele of Licinia Amias on marble, in the National Roman Museum. One of the earliest Christian inscriptions found, it comes from the early 3rd century Vatican necropolis area in Rome. It contains the text ΙΧΘΥϹ ΖΩΝΤΩΝ ("fish of the living"), a predecessor of the Ichthys symbol.

-

The eastern Mediterranean region in the time of Paul the Apostle

-

St. Lawrence (martyred 258) before Emperor Valerianus by Fra Angelico

-

A folio from Papyrus 46, an early-3rd-century collection of Pauline epistles

-

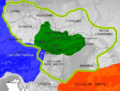

Early centers of Christianity to AD 325 Spread of Christianity to AD 600

-

Icon depicting the Emperor Constantine (centre) and the bishops of the First Council of Nicaea (325) holding the Niceno–Constantinopolitan Creed of 381.

-

Imagined portrait of Arius; detail of a Cretan School icon, c. 1591, depicting the First Council of Nicaea.

-

The ceiling mosaic of the Arian Baptistery, built in Ravenna by the Ostrogothic King Theodoric the Great.

-

An Eastern Roman mosaic showing a basilica with towers, mounted with Christian crosses, 5th century, Louvre

-

Coptic icon of St. Anthony the Great, father of Christian monasticism and early anchorite. The Coptic inscription reads ‘Ⲡⲓⲛⲓϣϯ Ⲁⲃⲃⲁ Ⲁⲛⲧⲱⲛⲓ’ ("the Great Father Anthony").

-

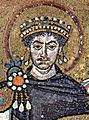

A mosaic of Justinian I in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy

-

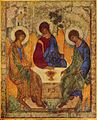

"Hospitality of Abraham", icon by Andrei Rublev; the three angels represent the Godhead according to Trinitarian Christians.

-

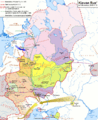

Western Europe, the Holy Roman Empire, Kievan Rus', and the Byzantine Empire in the Middle Ages (year 1000)

-

Jan Hus defending his theses at the Council of Constance (1415), painting by the Czech artist Václav Brožík

-

Michelangelo's Pietà (1498–99) in St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City

-

Philipp Spener, the founder of Pietism

-

Churches of the Moscow Kremlin, as seen from the Balchug

-

Demolition of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow on the orders of Joseph Stalin, 5 December 1931, consistent with the doctrine of state atheism in the USSR

-

Laying on of hands during a service in a neo-charismatic church in Ghana

See also

In Spanish: Historia del cristianismo para niños

In Spanish: Historia del cristianismo para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |