Toledo War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Toledo War |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The portion of the Michigan Territory claimed by the State of Ohio known as the Toledo Strip |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Ohio militia | Territory of Michigan militia | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

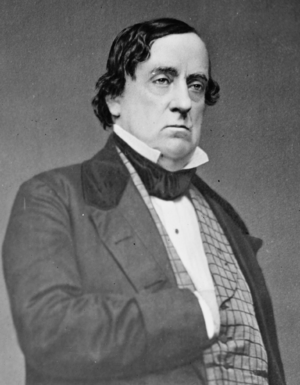

| Robert Lucas John Bell |

Stevens T. Mason Joseph W. Brown |

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 600 | 1,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| None | 1 wounded | ||||||||

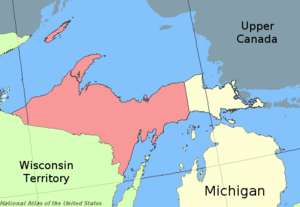

| In exchange for ceding the Toledo Strip, all of what is now known as the Upper Peninsula was included within Michigan's bounds when it was admitted into the Union in 1837 (only the easternmost portion of the peninsula had been claimed in Michigan's 1835 statehood petition). | |||||||||

The Toledo War was a disagreement over land between the state of Ohio and the Territory of Michigan from 1835 to 1836. This "war" was about a strip of land called the Toledo Strip. Both sides wanted this land because it had good farmland and important access to the Maumee River, which was great for shipping and trade.

The problem started because early maps of the Great Lakes weren't very accurate. This led to different laws about where the border should be. Both Ohio and Michigan claimed the same area of about 468 square miles. Things got serious when Michigan wanted to become a state in 1835. They wanted the Toledo Strip to be part of their new state. Both Ohio's Governor Robert Lucas and Michigan's young Governor Stevens T. Mason made rules. These rules made it against the law for people to follow the other side's government. Both sides even sent their citizen soldiers (militias) to the area near Toledo. They mostly just yelled at each other. The only real clash involved some shots fired into the air, but no one was hurt. An officer was injured with a penknife, but it was not serious.

In 1836, the United States Congress suggested a solution. Michigan would give up the Toledo Strip. In return, Michigan would become a state and receive the rest of the Upper Peninsula. At first, many people in Michigan thought this was a bad deal. The Upper Peninsula seemed like a wild, empty place. So, they voted against it in September. But Michigan was running out of money because of the conflict. Also, President Andrew Jackson and Congress put a lot of pressure on them. In December, Michigan held another meeting, known as the "Frostbitten Convention." This time, they accepted the deal, and the Toledo War finally ended.

Understanding the Toledo War

Why the Border Was Confusing

In 1787, a law called the Northwest Ordinance created the Northwest Territory. This huge area is now part of the Midwestern United States. The law said this territory would eventually become several new states. One important border was supposed to be an east-west line. This line would start at the very southern tip of Lake Michigan. When Ohio was getting ready to become a state in 1802, Congress used similar words. They said Ohio's northern border would run east from Lake Michigan's southern tip. It would continue until it met Lake Erie or the border with Canada.

Back then, the best maps, like the "Mitchell Map," were wrong. They showed the southern tip of Lake Michigan much further north. Based on these maps, Ohio's leaders thought their northern border would be north of the Maumee River. This would give Ohio a lot of the Lake Erie shoreline.

But then, some people heard from a fur trapper. He said Lake Michigan actually stretched much further south than the maps showed. This meant the east-west border line might cut through Lake Erie in a different spot. Or it might not even reach Lake Erie at all. If Lake Michigan was further south, Ohio would lose valuable land and access to the lake.

To avoid this, Ohio's leaders added a special rule to their state constitution. If Lake Michigan was indeed further south, their border would angle northeast. This would make sure the Maumee River area and the southern Lake Erie shore stayed with Ohio. Congress accepted Ohio's constitution. But a committee noted that the exact location of Lake Michigan's tip wasn't known. They decided not to worry about that detail at the time.

Later, in 1805, Congress created the Michigan Territory. They used the original Northwest Ordinance wording for Michigan's southern border. They didn't consider Ohio's special rule. This difference in wording created a problem. It set the stage for the big argument that happened 30 years later.

The Disputed Toledo Strip

The exact border was argued about for many years. People living in the area, which later became Toledo, wanted Ohio to fix the border. Ohio's government kept asking Congress to deal with it. In 1812, Congress agreed to an official survey. This was delayed by the War of 1812. The survey finally started after Indiana became a state in 1816. Around this time, Michigan's border with Indiana was changed. It moved 10 miles north, giving Indiana more access to Lake Michigan. Michigan was not happy about this.

Edward Tiffin, a former Ohio governor, was in charge of the survey. He hired William Harris to draw the border. Harris drew the line based on Ohio's constitution, not the original Northwest Ordinance. This "Harris Line" put the mouth of the Maumee River entirely in Ohio. Michigan's governor, Lewis Cass, was upset. He said the survey was unfair and favored Ohio.

Michigan then ordered its own survey, done by John A. Fulton. This "Fulton Line" followed the original 1787 Ordinance. It placed the Ohio border southeast of the Maumee River's mouth. The land between these two survey lines became the "Toledo Strip." This strip was about 5 to 8 miles wide. Both Ohio and Michigan claimed they owned it. Ohio wouldn't give up its claim. But Michigan quietly took control of the area for years. They set up local governments, built roads, and collected taxes there.

Why This Land Was Important

The Toledo Strip was a very important area for trade. Before railroads, rivers and canals were the main ways to move goods. The Maumee River flowed into Lake Erie. It was a key connection to places like Fort Wayne, Indiana. There were plans to build canals connecting the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes. One such canal, the Miami and Erie Canal, would use the Maumee River.

The Erie Canal, finished in 1825, connected New York City to the Great Lakes. It became a major route for trade and people moving west. Farm products from the Midwest could be shipped east much more cheaply. Many settlers moved west after the canal was built.

Because the western end of Lake Erie was the shortest route to Indiana and Illinois, Maumee Harbor was seen as very valuable. Detroit was further up the Detroit River and faced a large swamp to the south. This made Toledo a better spot for new transportation projects like canals and later, railroads. Both states knew they would gain a lot by controlling the Toledo Strip.

Also, the land west of Toledo was excellent for agriculture. It had rich, fertile soil. This area produced a lot of corn and wheat. So, both Michigan and Ohio wanted this land for its port and its farms.

Getting Ready for Conflict

By the early 1820s, the Michigan Territory had enough people to become a state. But when it asked to hold a meeting to write a state constitution in 1833, Congress said no. The Toledo Strip border was still a problem.

Ohio said its border was already set in its constitution. They saw Michigan's people as intruders. Ohio's leaders in Congress worked hard to stop Michigan from becoming a state.

In January 1835, Michigan's young governor, Stevens T. Mason, decided to act. He called for a meeting to write a constitution in May, even without Congress's approval.

In February 1835, Ohio passed laws to set up county governments in the Strip. The county where Toledo was located was named after Ohio's governor, Robert Lucas. This made tensions with Michigan even worse. Ohio also tried to get Congress to officially set the border as the Harris Line.

Michigan's Governor Mason responded quickly. He passed the Pains and Penalties Act. This law made it against the rules for Ohio officials to act in the Strip. People who broke this rule could face serious consequences. Mason put Brigadier General Joseph W. Brown in charge of Michigan's citizen soldiers. He told them to be ready to stop Ohio's actions. Governor Lucas also got approval for his own citizen soldiers. He soon sent them to the Strip. The Toledo War had officially begun.

Former U.S. President John Quincy Adams, who was then in Congress, supported Michigan. He said that Michigan clearly had the right side of the argument, but Ohio had all the power.

The 'War' Begins

Governor Lucas, leading about 600 armed citizen soldiers, arrived near Toledo on March 31, 1835. Soon after, Governor Mason and General Brown arrived in Toledo with about 1,000 armed men. They wanted to stop Ohio from moving into the area and from marking the border.

President Jackson Steps In

President Andrew Jackson wanted to stop a real fight. He asked his legal advisor, Benjamin Butler, for advice. Ohio was a powerful state with many representatives in Congress. Michigan was still just a territory. Jackson knew his political party needed Ohio's support. Butler said the land belonged to Michigan until Congress decided otherwise. This was a tough problem for Jackson.

On April 3, 1835, Jackson sent two representatives from Washington, D.C. to Toledo. They were Richard Rush and Benjamin Chew Howard. They tried to find a peaceful solution. Their idea, presented on April 7, was to re-survey the Harris Line. Michigan should not stop this survey. Also, people living in the disputed area could choose which government to follow until Congress made a final decision.

Lucas agreed to this idea and started sending his citizen soldiers home. He thought the problem was solved. Three days later, elections were held under Ohio law in the region. Mason, however, refused the deal. He kept preparing for a possible fight.

During the elections, Michigan authorities bothered Ohio officials. Residents were told they would be arrested if they followed Ohio's rules. On April 8, a Michigan sheriff arrested two Ohioans. They were taken into custody for voting in the Ohio elections.

The Phillips Corners Incident

After the election, Lucas believed the situation was calmer. He sent surveyors out again to mark the Harris Line. Everything was quiet until April 26, 1835. Then, about 50 to 60 Michigan citizen soldiers attacked the surveying group. This event is known as the Battle of Phillips Corners. It was the only time there was any armed conflict.

The surveyors later wrote to Lucas about what happened. They said Michigan forces told them to leave. During the chase, nine of their men were captured. They were taken to Tecumseh, Michigan. Michigan claimed they only fired a few musket shots into the air as the Ohio group ran away. But this incident made both Ohioans and Michiganders very angry. It brought them very close to a full-scale war.

Tensions Rise in 1835

Because of the reports that Michigan's citizen soldiers had fired shots, Lucas called a special meeting of Ohio's government. On June 8, they passed more laws. These laws made Toledo the main town for Lucas County. They also set up a court in the city. A budget of $300,000 was approved to put these laws into action. Michigan's government responded with its own budget of $315,000 to pay for its citizen soldiers.

In May and June, Michigan wrote its own state constitution. It included plans for a government with a legislature and a supreme court. But Congress still would not let Michigan become a state. President Jackson said he would not approve Michigan's statehood until the border problem was solved.

Lucas's general, Samuel C. Andrews, counted the Ohio citizen soldiers. He reported that 10,000 volunteers were ready to fight. This news grew bigger as it traveled north. Soon, Michigan newspapers were daring Ohio's "million" soldiers to enter the Strip.

In June 1835, Lucas sent a group to Washington D.C. to talk with President Jackson. They explained Ohio's side and asked Jackson to fix the situation quickly.

Throughout mid-1835, both governments continued to challenge each other. There were constant small fights and arrests. People from Monroe County, Michigan, tried to make arrests in Toledo. Ohio supporters, angry about this, tried to bring charges against those involved. Many lawsuits were filed by both sides. People on both sides also spied on the sheriffs of Wood County, Ohio, and Monroe County, Michigan.

On July 15, a Michigan deputy sheriff went to Toledo to arrest Major Benjamin Stickney. Stickney and his family fought back. During the struggle, Stickney's son, Two Stickney, injured the deputy with a penknife. He then ran into Ohio. The deputy's injuries were not life-threatening. Mason asked Lucas to send Two Stickney back to Michigan for trial. Lucas refused. Mason then asked President Jackson for help. Jackson declined, saying it was not a matter for the United States Supreme Court. Lucas then tried to end the conflict through Ohio's representatives in Congress.

In August 1835, because Ohio's members of Congress pushed hard, Jackson removed Mason as Michigan's governor. He appointed John S. ("Little Jack") Horner instead. Before Horner arrived, Mason ordered 1,000 Michigan citizen soldiers to go to Toledo. He wanted to stop the first important meeting of the Ohio Court of Common Pleas. This idea was popular in Michigan, but it failed. The judges held a quick midnight court session. Then they quickly went south of the Maumee River, where Ohio forces were waiting.

How the War Ended

Horner was not popular as governor and did not stay long. People disliked him so much they burned a dummy of him. They also threw vegetables at him when he arrived in the capital. In the October 1835 elections, voters approved the new constitution. They also re-elected Mason as governor. Isaac E. Crary was chosen as Michigan's first representative to Congress. But because of the dispute, Congress would not let him vote. Michigan's two senators, Lucius Lyon and John Norvell, were treated with even less respect. They were only allowed to watch from the Senate gallery.

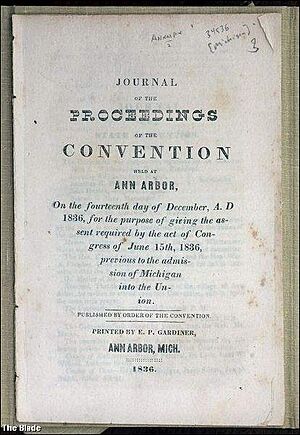

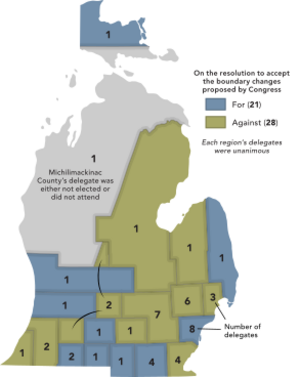

New states were usually admitted in pairs to keep a balance between states that allowed slavery and those that did not. On June 15, 1836, Arkansas became the 25th state. President Jackson then signed a bill allowing Michigan to become a state. But Michigan had to give up the Toledo Strip. In return, Michigan would get the western three-quarters of the Upper Peninsula. At the time, people thought the Upper Peninsula was a remote wilderness, not good for farming. So, in September 1836, a special meeting in Ann Arbor rejected this offer.

As the year went on, Michigan faced a serious money problem. The high costs of its citizen soldiers had almost bankrupted the government. They also realized that a large amount of money from the U.S. Treasury was about to be given to the 25 states. Michigan, as a territory, would not get any of it.

The war unofficially ended on December 14, 1836. This happened at a second meeting in Ann Arbor. The delegates voted to accept Congress's terms. Calling this meeting was controversial. It happened because many people privately called for it. Since the legislature did not officially approve the meeting, some said it was illegal. The Whigs refused to attend. Because of this, many Michigan residents made fun of the decision. Congress questioned if the meeting was legal, but they accepted its results. These factors, plus a very cold spell, led to the event being called the Frostbitten Convention.

On January 26, 1837, Michigan officially became the 26th state. It did not get the Toledo Strip, but it received the entire Upper Peninsula.

What Happened After the War

The Toledo Strip became a permanent part of Ohio. At first, most people thought the Upper Peninsula was a worthless wilderness. They thought it was only good for timber and fur trapping. However, in the 1840s, copper was found in the Keweenaw Peninsula. Iron was also discovered in the Central Upper Peninsula. This led to a huge mining boom that lasted for many years. Michigan lost about 1,100 square miles of farmland and the port of Toledo. But it gained about 9,000 square miles of land rich in timber and ore.

Disagreements about the exact border continued until a new survey was done in 1915. The surveyors usually follow the old lines exactly. But this time, they made small changes in some places. This was to prevent people from suddenly living in a different state. It also stopped landowners from having property in both states. The 1915 survey used 71 granite markers to show the border. When it was finished, the governors of Michigan and Ohio shook hands at the border.

You can still see traces of the original Ordinance Line today. It is in northwestern Ohio and northern Indiana. The northern borders of Ottawa and Wood counties follow it. Many township borders in Fulton and Williams counties also do. Many old north-south roads are offset where they cross this line. This forces traffic to jog east when traveling north. Maps from the United States Geological Survey show it as the "South Michigan Survey." Local road maps call it "Old State Line Road."

Even after the land border was set, the two states still disagreed about the border in Lake Erie. In 1973, they went to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court ruled that the border in Lake Erie angled to the northeast. This was as described in Ohio's state constitution. This meant that Turtle Island, near Maumee Bay, was split between the two states.

This decision was the last border change. It finally ended years of debate. Today, there is still a friendly rivalry between people from Michigan and Ohio. This is mostly seen in college American football games between Michigan and Ohio State. The Toledo War is sometimes mentioned as the start of this rivalry.

Images for kids

-

USGS topographic map that shows the Ordinance Line as "South Bdy Michigan Survey". There are jogs in many north–south roads at this line.

-

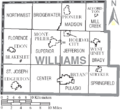

The northern tier of townships in Williams County are within the Toledo Strip. The southern boundary of each lies along the Ordinance Line.

-

The northern half of Dover Township in Fulton County Ohio, formerly claimed by Michigan, is shifted, or "jogs", at "Old State Line Road", now County Road K.

See also

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- List of Michigan county name etymologies

- Ohio Lands

- Timeline of the Toledo Strip

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |