Trafalgar campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Trafalgar campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Third Coalition | |||||||

|

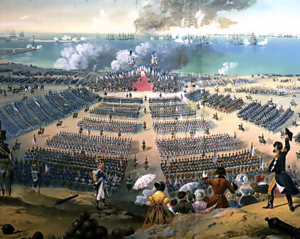

Click image to load the battle. The Battle of Trafalgar, by Clarkson Frederick Stanfield |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 70 ships of the line | 56 ships of the line | ||||||

The Trafalgar campaign was a long and tricky series of naval moves in 1805. It involved the combined fleets of France and Spain against the Royal Navy of Britain. These actions were the final part of France's plan to invade the United Kingdom. The French leader, Napoleon, had very complex ideas. But he didn't fully understand how the sea, weather, and British navy worked. Even with some small successes, the French commanders could not complete their main goal. The campaign covered thousands of miles of ocean. It included several sea battles, especially the famous Battle of Trafalgar on October 21. In this battle, the French and Spanish fleets were completely defeated. The campaign gets its name from this battle. A final battle at Cape Ortegal on November 4 finished off the combined fleet. This made sure the Royal Navy stayed the most powerful navy at sea.

Contents

- Why They Fought: French and British Goals

- Napoleon's Changing Plans for Invasion

- The Situation in March 1805

- The Trafalgar Campaign: Napoleon's New Plan

- Villeneuve in the West Indies

- Nelson's Chase in the West Indies

- Villeneuve is Stopped

- The Battle of Trafalgar

- Battle of Cape Ortegal

- What Happened Next: Outcome and Importance

Why They Fought: French and British Goals

Napoleon had wanted to invade England for a long time. He first gathered an army on the coast in 1798. But his plans were put on hold until 1803. Then, he brought his forces together again near Boulogne. They were getting ready for the invasion fleet to cross the English Channel.

The Royal Navy was the biggest problem for Napoleon. He believed his fleet only needed to control the Channel for six hours. That would be enough time for his invasion force to cross safely. The British knew where the French ships were gathering. They kept a close watch on them. The British wanted to stop the French at all costs. The French hoped to get temporary control of the Channel.

Napoleon's Changing Plans for Invasion

Napoleon came up with four different plans between 1804 and 1805. Each plan aimed to gather a large fleet of ships. Then, they would move up the Channel. A common idea in these plans was to trick the British navy. This would draw them away from the Channel. Then, the French fleets would join together. They would free any ships stuck in port. Finally, the combined fleet would sail to Boulogne. There, they would protect the invasion force as it crossed.

First Plan: Summer 1804

Napoleon's first plan was for July to September 1804. It involved 10 French ships from Toulon under Admiral Latouche Tréville. They would try to avoid the British fleet led by Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson. Then, they would sail into the Atlantic Ocean. After that, they would head to Rochefort to pick up more ships.

At the same time, Vice-Admiral Ganteaume would sail from Brest with 23 ships. He hoped to draw the main British Channel Fleet away. If this worked, Latouche Tréville would have a clear path to Boulogne. He could then escort the invasion fleet. This plan was very complicated. It relied on good weather and avoiding British ships. It also needed the British to be tricked. The plan was never put into action. Latouche Tréville stayed in Toulon. He died suddenly in August, ending this idea.

Second Plan: Late 1804 to Early 1805

After Latouche Tréville died, Napoleon made a bigger plan. It had three main parts.

- First, Vice-Admiral Villeneuve would leave Toulon with 10 ships and 5,600 troops. He would try to avoid Nelson. After picking up a ship from Cádiz, he would sail to the West Indies. Two of his ships would go to capture Saint Helena and cause trouble in West Africa.

- Second, Rear-Admiral Missiessy would sail from Rochefort with six ships and 3,500 troops. He would also go to the West Indies. There, he would strengthen French bases and capture British islands like Dominica. Villeneuve and Missiessy would then join forces. They would capture more places before sailing back to Europe.

- Third, Ganteaume would leave Brest with 21 ships and 18,000 troops. He would sail around Scotland to Lough Swilly in Ireland. There, he would land his troops for an invasion of Ireland. After that, Ganteaume would meet Villeneuve and Missiessy returning from the West Indies. With nearly 40 ships, they would clear the Channel. Then, they would escort the invasion of England.

This plan was almost impossible. It depended on perfect weather, no British interference, and easy communication over vast distances. The British found out about Ganteaume's orders. So, the whole project was called off.

Third Plan: January 1805

By January 1805, things in Europe had changed. Spain had joined France. But Napoleon was worried about Austria and Russia. They seemed to be talking with Britain. He realized it was risky to send most of his forces across the Channel. They would be hard to call back if needed.

Napoleon decided to pause his invasion plans. He came up with a new idea. His fleets could cause trouble for Britain elsewhere. Villeneuve and Missiessy were ordered to take their fleets to the West Indies. They would attack British colonies there. This would force Britain to send ships to defend them.

Missiessy left Rochefort on January 11. He avoided the British ships watching the port. He sailed into the Atlantic. Rear-Admiral Alexander Cochrane chased him, and both fleets went to the West Indies.

Villeneuve finally sailed from Toulon on January 18. He went out into a strong storm. British frigates saw them leave. They quickly told Nelson, who was anchored nearby. Nelson immediately took his fleet to sea. He thought Villeneuve was heading east to attack places like Italy or Egypt. He sailed south, but the French ships didn't appear. He went further east, checking Greece and then Alexandria. He found no news of the French.

Nelson turned west, stopping at Malta. There, he learned the French were back in Toulon. Villeneuve had turned back just two days after leaving. The bad weather and his ships' problems forced him to return. The British frigates had left the French fleet unwatched. This meant Nelson spent six weeks sailing around the Mediterranean. All that time, the French were safe in port. A frustrated Nelson went back to watching Toulon.

The Situation in March 1805

Most of the French Navy was stuck in port. British fleets were blocking them. The main French invasion army of 93,000 men waited in Boulogne.

- A combined French and Dutch group of nine ships was in the Netherlands.

- The main British Channel Fleet had 15 ships. They patrolled between Ushant and Ireland.

- Other British groups blocked French ports like Rochefort and Ferrol.

- The French had 21 ships at Brest.

- Spain had ships at Ferrol, Cádiz, and Cartagena.

- The French base at Toulon had 11 ships under Villeneuve. Nelson's 12 British ships kept them blocked.

Far away, Missiessy was sailing around the West Indies. He was being chased by Cochrane. Napoleon called Missiessy back to France when he learned Villeneuve was still stuck in Toulon. Missiessy started his journey back on March 28.

In March 1805, Napoleon got good news. Austria said they would not go to war with France. Napoleon decided to restart his plan to invade Britain. He drew up a new plan.

The Trafalgar Campaign: Napoleon's New Plan

The new plan involved several fleets joining up.

- Ganteaume's fleet at Brest would take 3,000 troops. They would sail to Ferrol. There, they would chase away the British ships blocking the port. Then, they would join with the French and Spanish ships already there. This would create a force of 33 ships. They would then sail to Martinique in the West Indies.

- Meanwhile, Villeneuve would take 3,000 troops and sail from Toulon. He would break out into the Atlantic. After picking up seven more ships from Cádiz, he would also sail to the West Indies.

- The three fleets—Ganteaume's, Missiessy's (if he was still there), and Villeneuve's—would meet. They would then sail back across the Atlantic. They would clear any British resistance. Finally, they would protect the invasion fleet crossing the Channel.

Ganteaume Blocked at Brest

Ganteaume had his fleet ready by March 24. But Vice-Admiral Cotton's 17 British ships were closely blocking Brest. Ganteaume had orders to avoid battle. He waited for good conditions. On March 26, a fog came down. He hoped it would help him slip past the British. But as he left, the weather suddenly changed. The fog cleared, and it became hard to return to port.

Ganteaume was temporarily stuck outside the harbor. He got ready for battle as Cotton's force came closer. But Cotton did not risk a fight. It was getting dark, there were many shallow areas, and the French ships were under the protection of shore cannons. So, Cotton just watched and kept blocking Ganteaume. The next day, the wind changed. This allowed Ganteaume to return to port. He stayed there for the rest of the campaign.

Villeneuve Escapes Toulon

Villeneuve and his second-in-command, Rear-Admiral Pierre Dumanoir le Pelley, quickly got the Toulon fleet ready. Nelson had been seen near Barcelona. Villeneuve hoped that by sailing south from Toulon, he could avoid the British ships. But Nelson was setting a trap. He had let himself be seen off the Spanish coast. Then, he moved south of Sardinia. He hoped Villeneuve would sail right into him while trying to avoid his supposed location.

Villeneuve set sail on March 30. British frigates Active and Phoebe saw him. As Nelson hoped, Villeneuve set a course between the Balearic Islands and Sardinia. The frigates lost sight of the French fleet on April 1. On the same day, Villeneuve met a Spanish merchant ship. He learned that Nelson had been seen off Sardinia. Realizing he was sailing into a trap, Villeneuve turned west. He passed to the west of the Balearics.

With no visual contact, Nelson didn't know where the French fleet was going. Villeneuve hurried to Cartagena. But he didn't wait for the Spanish ships there. They wouldn't join him until orders came from Madrid. Instead, he rushed on. He passed through the Strait of Gibraltar on April 8. The British squadron under Sir John Orde saw him. From Cádiz, Villeneuve picked up the French 74-gun ship Aigle. Then, he set off across the Atlantic to the West Indies. Six Spanish ships and a frigate under Federico Gravina followed him.

Meanwhile, Nelson had been told the French had left. But he couldn't find them off Sardinia. He used his frigates to search for any news. He finally figured out that the entire French force must have left the Mediterranean. He sailed through the straits himself. On May 8, one of Orde's ships confirmed that the French had passed through a month earlier. They had not gone north. Nelson was sure Villeneuve was headed for the West Indies. He set off in pursuit.

Villeneuve in the West Indies

Villeneuve arrived at Fort de France, Martinique, on May 14. The Spanish ships under Gravina joined him over the next two days. After getting supplies, Villeneuve waited for Ganteaume. He didn't know Ganteaume was still blocked in Brest.

Villeneuve didn't want to attack British colonies without orders. But after two weeks of waiting, the Governor of Martinique convinced him. He attacked the British-held Diamond Rock. The small British group there surrendered on June 2. By then, the frigate Didon arrived with new orders. Villeneuve was told to wait for two more ships. Then, he should spend a month attacking and capturing British colonies in the West Indies. After that, he was to sail his entire force back to Europe. He would join Ganteaume at Brest and protect the invasion fleet. The orders also mentioned that Nelson had sailed to Egypt looking for him.

In fact, Nelson was only two days away from Barbados. He would anchor there on June 4. Villeneuve gathered his forces and sailed north towards Antigua. On June 7, he found a group of British merchant ships with little protection. He captured several the next day. From them, he learned that Nelson had arrived at Barbados. Villeneuve was shocked. He decided to stop his operations and head back to Europe. The fleet left on June 11. One army officer with the fleet, General Honoré Charles Reille, wrote:

We have been masters of the sea for three weeks with a landing force of 7000 to 8000 men and have not been able to attack a single island.

Nelson's Chase in the West Indies

Nelson arrived at Barbados on June 4. He got reports that the French had been seen sailing south a week earlier. Nelson chased them. But the information was wrong. Villeneuve and his fleet were north of Barbados and moving further north each day.

A series of wrong sightings and false information kept Nelson heading south. On June 8, he finally got clearer news. Villeneuve was north of him and heading towards Antigua. Nelson reached Antigua on June 12. He learned that Villeneuve had passed by the day before, heading for Europe. Nelson left in pursuit on June 13. He thought Villeneuve would either go to Cádiz or try to re-enter the Mediterranean.

Villeneuve was actually heading for Ferrol. Nelson set his course too far south, hoping to catch them at sea. He missed them. Nelson finally arrived at Gibraltar on July 19. After that, he sailed his fleet to join the Channel Fleet. Then, he took his ship, Victory, into Portsmouth.

Villeneuve is Stopped

Nelson had sent messages back to the Admiralty. These messages were carried by the brig HMS Curieux. While sailing across the Atlantic, Curieux spotted the combined French and Spanish fleet on June 19. They were sailing north from Antigua. Curieux followed them. It figured out they were not heading for the Straits as Nelson thought. They were likely going to the Bay of Biscay.

The messages and news were rushed to Lord Barham at the Admiralty. He ordered a stronger British fleet under Vice-Admiral Robert Calder to stop the combined fleet. This would happen as they arrived off Cape Finisterre. Calder received five extra ships. On July 22, the enemy fleet was seen heading west towards Ferrol.

Calder then moved south to stop them. Villeneuve arranged his ships into a battle line and began moving north. The two fleets slowly passed each other. Then, Calder turned his ships around and began to close in on the enemy's rear. The battle started when the British frigate HMS Sirius attacked the French frigate Siréne. This ship was at the back of the French line.

Villeneuve feared the British were trying to cut off his rear. He turned his fleet around. The Spanish ships at the front of his line opened fire on the leading British ships around 5:30 PM. The fighting quickly spread. But in the fading light, mist, and gunsmoke, both fleets soon became scattered. By the time the fighting stopped at 9:30 PM, two Spanish ships had been cut off and captured.

Both fleets were still scattered the next day. They kept watching each other. But neither tried to restart the battle. Even with better winds on July 24, Calder chose not to fight. By July 25, the fleets had drifted out of sight. Villeneuve sailed south to Vigo. Calder headed east. Both admirals claimed a victory. Villeneuve told Napoleon he planned to sail north to meet another French force. Then, he would head to the Channel.

On August 10, off Cape Finisterre, HMS Phoenix captured the French frigate Didon. Didon was carrying messages. These messages told Rear-Admiral Allemand's five ships to join Villeneuve's combined fleet.

While sailing to Gibraltar with his captured ship, Captain Baker met the British ship HMS Dragon on August 14. The next day, Villeneuve's combined fleet saw the three British ships. Villeneuve was heading for Brest and then Boulogne. He was supposed to escort the French invasion forces across the Channel. But Villeneuve thought the British ships were scouts from the Channel Fleet. He fled south to Cadiz to avoid a fight.

Napoleon was furious. He said, 'What a Navy! What an admiral! All those sacrifices for nought!' The battle of Finisterre and Villeneuve's retreat became the most important event for the invasion of England. Napoleon gave up all hope of controlling the Channel. He gathered his invasion army, now called the Grande Armée. He marched them east to attack the Austrians in the Ulm Campaign.

The Battle of Trafalgar

Villeneuve's fleet was repaired in Cádiz. British warships quickly formed a blockade around them. Rear-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood first led this blockade. From September 27, Vice-Admiral Nelson took command. He had arrived from England. Nelson spent weeks getting his battle plans ready. He also had dinner with his captains. This made sure they understood his ideas.

Nelson had a new plan of attack. He expected the enemy fleet to form a traditional line of battle. Nelson decided to split his fleet into groups. Instead of forming a line parallel to the enemy, his groups would cut the enemy's line in several places. This would create a confused, close-quarters battle. British ships could then surround and destroy parts of the enemy's formation. The other enemy ships would not be able to help in time.

Napoleon was very unhappy with Villeneuve. He ordered Vice-Admiral François Rosily to go to Cádiz. Rosily was to take command of the fleet. He was to sail it into the Mediterranean to land troops in Naples. Then, he would go to Toulon. Villeneuve decided to sail the fleet out before his replacement arrived.

On October 20, patrolling British frigates saw the fleet leaving the harbor. Nelson was told they seemed to be heading west. Nelson led his column of ships into battle aboard HMS Victory. He successfully cut the enemy line. This started the close-quarters battle he wanted. After several hours of fighting, 17 French and Spanish ships were captured. Another was destroyed. Not a single British ship was lost.

Nelson was among the 449 British dead. He was badly wounded by a French sharpshooter during the battle. Nine of the captured ships later sank or were destroyed in a storm the next day. Some ships that escaped tried to recapture the Spanish ship Santa Ana. But in doing so, they lost three more ships in the storm. A fourth was captured by the British but later wrecked. The British fleet and the remaining captured French ships sailed into Gibraltar over the next few days.

Battle of Cape Ortegal

The combined fleet was completely crushed at Trafalgar. But the final action of the campaign happened almost two weeks later, on November 4. Four French ships under Rear-Admiral Pierre Dumanoir le Pelley had escaped Trafalgar. They headed north, hoping to reach Rochefort. On November 2, they found the 36-gun frigate HMS Phoenix. This was about 40 miles off Cape Ortegal.

The French ships chased the Phoenix. But the Phoenix led them towards a group of five British ships. This group was under Captain Sir Richard Strachan. Strachan led his ships in pursuit. He came within range and started the attack on November 4. One of his ships was not even with the group yet.

Strachan used his frigates to bother and weaken the enemy. They avoided the enemy's main gun attacks. Strachan used his larger ships to attack the French ships from the rear and middle. He was eventually able to surround the French ships. After four hours of close fighting, all the French ships were forced to surrender.

What Happened Next: Outcome and Importance

By early November, the combined French and Spanish fleet was almost completely destroyed.

- Two ships were lost at Finisterre.

- Twenty-one were lost at Trafalgar and in the storm that followed.

- Four were lost at Cape Ortegal.

- No British ships were lost in these battles.

Many of the French or Spanish ships that survived were badly damaged. They would not be ready for service for a long time. The British victory gave them complete control of the seas. This protected British trade and supported the Empire.

Napoleon's continued failure to manage his navies, unlike his armies, meant the invasion of England never happened. It had already been delayed several times. Villeneuve's defeat at Finisterre and his final failure to meet the other French fleets made Napoleon give up his invasion plans. He gathered his army and marched east to attack the Austrians.

Trafalgar, with its 74 ships, was the last battle of its size in the Napoleonic Wars. After 1805, the biggest battles involved no more than a dozen ships. The morale of the French navy was destroyed after 1805. Being constantly blocked in port made them less effective and less willing to fight. Napoleon thought about invading England again years later. But he never had the same focus or determination. His navy's failure left him disappointed. The shyness of its commanders and the British determination to fight them, shown throughout the Trafalgar campaign, left the French navy without a clear purpose.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |