Twin City Rapid Transit Company facts for kids

|

|

| Industry | Public transport |

|---|---|

| Fate | Streetcar system dismantled completely in 1954, sold in 1970 |

| Successor | Metro Transit |

| Founded | 1875 |

| Defunct | 1970 |

| Headquarters | Minneapolis-St. Paul |

|

Key people

|

Thomas Lowry, Horace Lowry, Charles Green, Fred Ossanna, Carl Pohlad |

| Products | streetcars, horse-drawn buggies, buses |

|

Number of employees

|

1000 (estimated) |

| Parent | Twin City Lines |

| Subsidiaries | Minneapolis Street Railway Company, St. Paul City Railway Company, Minneapolis & St. Paul Suburban Railroad Company, Twin City Motor Bus Company, Minnetonka and White Bear Navigation Company, Rapid Transit Real Estate Corporation, Transit Supply Company |

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locale | Minneapolis-St. Paul | ||||||||||||||||

| Open | 1876 | ||||||||||||||||

| Close | 1954, sold in 1970 | ||||||||||||||||

| Status | defunct | ||||||||||||||||

| Owner(s) | Twin City Rapid Transit | ||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Twin City Rapid Transit | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

The Twin City Rapid Transit Company (TCRT), also known as Twin City Lines (TCL), was a big transportation company. It ran streetcars and buses in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area of Minnesota. At its busiest, in the early 1900s, it had one of the best streetcar systems in the United States. Today, the Metro Transit bus and light rail system continues its work in the area.

Contents

How the Streetcar System Started

The first street rail transport in the Twin Cities began around 1865. A businessman named Dorilus Morrison started building rails in downtown Minneapolis. He soon teamed up with others to create the Minneapolis Street Railway. However, these early lines didn't go very far and weren't used much at first.

Across the Mississippi River, the St. Paul Railway Company started the first successful horse-drawn streetcar system in St. Paul. In 1875, the Minneapolis Street Railway made a deal with the Minneapolis City Council. They got special rights to street rails for 50 years if they could start operating within four months. Real-estate expert Thomas Lowry helped them, and on September 2, 1875, a route opened between downtown Minneapolis and the University of Minnesota.

Streetcars became very popular because they rode on smooth rails. Most streets back then were dirt or cobblestone, which were bumpy and hard to travel on. This was especially true during the cold Minnesota winters.

Thomas Lowry wanted to connect all the different railways in Minneapolis. While other systems used more horse-drawn carriages or cable cars, Lowry pushed for using electricity. By the late 1880s, electric streetcars started running in both Minneapolis and St. Paul. Cable cars and slow horsecars quickly became less popular.

Growth of the Streetcar Network

In 1890, the two cities were connected by a railway along University Avenue. This was the first of four rail lines linking them. The St. Paul City Railway Co. and Minneapolis Street Railway then merged to form the Twin City Rapid Transit Company. The new company quickly built many more electric tracks, doubling the system's size.

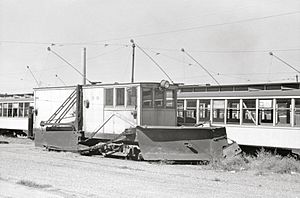

For the next 40 years, TCRT kept buying smaller rival companies. In 1898, the company started building its own streetcars and equipment. This included cranes and snowplows, instead of buying them from other companies. The first special car was built for the company president, Thomas Lowry. It had large windows to enjoy the view and was used for special events, like new line openings or visits from important people like President William McKinley.

TCRT built some of the largest streetcars in the country. They decided to build their own cars because those from other companies couldn't handle Minnesota's tough winters. By 1906, they opened a big manufacturing facility called Snelling Shops. They built cars not only for TCRT but also for cities like Chattanooga, Duluth, Seattle, and Chicago. These cars were very large, about 45 feet (13.7 meters) long and 9 feet (2.7 meters) wide.

Older tracks were also improved. Some early lines had used narrow tracks, but these were all updated to standard gauge tracks. The way the tracks were built also got better. TCRT's rails were some of the most expensive in the country, costing about US$60,000 per mile. They had welded joints and were often surrounded by cobblestone or asphalt. By 1909, almost all the rails were built this way, and they lasted until streetcar service ended.

From 1906 to 1926, TCRT tried out "streetcar boats." These were steam-powered boats that looked like streetcars. They traveled between towns on Lake Minnetonka. However, better roads in the area meant fewer people used the boats by the 1920s. Seven boats were built in total, but most were sunk in the lake in 1926.

TCRT also got into the amusement park business. They opened Wildwood Amusement Park on White Bear Lake and Big Island Park on Lake Minnetonka. Large ferry boats took people from Excelsior to the park on Big Island.

The company also noticed the rise of cars and buses. They bought several bus lines that started appearing around World War I. They also bought a taxicab company in the 1920s.

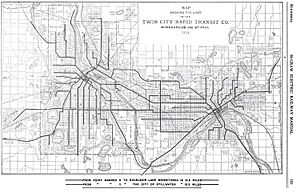

At its peak in 1922, the transportation system had almost 530 miles (853 kilometers) of track and 1021 streetcars. The rails stretched about 50 miles (80 kilometers) from Stillwater in the east to Lake Minnetonka in the west. For a while, TCRT was the biggest employer in the area. It's said that almost everyone in Minneapolis lived less than a quarter-mile (400 meters) from a streetcar stop.

Changes in Working Conditions

In 1917, a big strike happened after the United States entered World War I. It began on October 6 and was influenced by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a group that helped organize unions. Horace Lowry, Thomas Lowry's son, was in charge of TCRT and refused to talk with the striking workers. This made workers and their supporters very angry.

Angry strikers in St. Paul damaged streetcars and bothered those who kept working. The Minnesota Commission of Public Safety ordered the workers back to their jobs, and they followed for a short time. But in late November, many workers left again. On December 2, a crowd became angry after TCRT turned off electricity to streetcars in downtown St. Paul, leaving many people unable to get home. Many people were arrested, and the strike ended. About 800 striking workers were replaced by new workers who were not part of a union.

Things changed in the 1930s. In 1932, most streetcars were changed to "one-man operation." This meant one person, the motorman, drove the streetcar and also collected fares. Before, there was a motorman and a conductor. The doors on the streetcars were changed to make it easier for people to get on in the front. This change was happening on many streetcar lines across the country.

With one-man operation, about half of the company's workers were no longer needed. Many employees found it hard to get work and often had to work very strange hours. One worker reported a 17-hour shift. By October 1933, the workers got support from Minnesota Governor Floyd B. Olson and St. Paul Mayor William Mahoney. The next year, the workers voted to join the Amalgamated Transit Union.

Competition from Cars

With the Great Depression and more people owning automobiles, the rail lines started to decline. Buses were often used on longer routes or those with fewer riders. World War II helped the system for a while because people saved fuel and didn't use their cars as much. However, TCRT also had trouble building new streetcars due to wartime limits. The company had to add more buses to keep its routes running.

After the war, people went back to using their cars. TCRT's leaders looked for ways to improve the system and bring riders back. The rails needed repairs after heavy use during the war. In 1945, the company got its first modern PCC streetcar. In the following years, dozens of new PCC cars were added. These PCCs were a few inches wider than standard to match TCRT's older, wider streetcars.

Company Changes and Decline

TCRT usually used its profits to pay off loans and improve its rails and streetcars. It rarely paid out money to its shareholders. In 1948, a Wall Street investor named Charles Green bought many shares of TCRT stock. He expected to make money quickly, but then the company decided to start a lot of new construction. Knowing this would reduce his expected profits, Green convinced other shareholders to vote out the company's president and put him in charge.

Green took control of the company in 1949. He quickly started taking apart the railway system, saying the company would switch completely to buses by 1958. The company's modern PCC streetcars were sold to Mexico City, Newark, New Jersey, and Shaker Heights, Ohio. Green sold his shares in 1950. After a short time with Emil B. Anderson, local lawyer Fred Ossanna became the head of the company the next year. Ossanna paused the changes for a bit but then sped up the process. He announced that lines would be removed and replaced by buses in just two years.

The End of the Streetcar System

On June 19, 1954, the very last streetcars ran in Minneapolis. This was four years earlier than Charles Green had planned. The remaining streetcars were burned to get the metal inside them. A famous photo shows the last streetcar burning behind Fred Ossanna and James Towley.

At this time, TCRT faced several challenges. New highways allowed people to live farther away from the city center. The populations of Minneapolis and St. Paul started to spread out into less crowded suburbs. Building new rail lines to these areas would have been too expensive for the number of people who would use them. Buses, however, could make money on these routes. Many other streetcar lines in other cities had also switched to buses long before TCRT did.

Fred Ossanna started working at TCRT as a lawyer for Charles Green during the 1949 takeover. It is said that Ossanna planned to order 25 buses from General Motors but was offered 525 instead. Most of the buses TCRT ended up using were built by GM.

Much of the company's activity focused on selling off TCRT's valuable things to benefit the owners and investors. Fred Ossanna was later found to have improperly gained personal money from the company during this time. He was sent to prison along with others involved. Carl Pohlad, who later owned the Minnesota Twins baseball team, took over Twin City Lines in the 1960s. He eventually sold the company in 1970.

Saving Old Streetcars

Before the streetcar system was taken apart, TCRT had bought many modern PCC streetcars. These were sold off in 1952 and 1953 while they were still in good working condition. The cars went to Mexico City (91 cars), Newark, New Jersey (30 cars), and Shaker Heights, Ohio (20 cars). Not many places could use them because they were extra wide. These buyers had special tracks that could handle the wider cars. Most of the older wooden streetcars, which TCRT built itself, were destroyed. Out of 1240 built by the company, only five have been saved and restored by museums.

Only two of the wooden streetcars were given to groups interested in trains before the rest were burned. They are now owned by the Minnesota Streetcar Museum (TCRT No. 1300) and the Seashore Trolley Museum (TCRT No. 1267) in Maine. Another steel-covered car (TCRT No. 1583) was sent to a railway in Duluth-Superior but was never used there. It is now at the East Troy Electric Railroad Museum in Wisconsin. A few other cars avoided being burned, but they were in bad shape, and only two have been restored.

One of the streetcar boats, the Minnehaha, was found by divers and brought to the surface in 1980. After a long wait, it was restored and has been operating on Lake Minnetonka. The Minnesota Transportation Museum also restored one of TCRT's old PCC cars (TCRT No. 322), which is now operated by the Minnesota Streetcar Museum.

Many PCC cars that once belonged to Twin City Rapid Transit are now becoming museum pieces. The Newark City Subway stopped using its remaining 24 cars on August 24, 2001, replacing them with new light-rail trains. Fifteen of these cars were sold to the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni) for their collection of classic streetcars. Also, 12 PCCs from the Shaker Heights line are now owned by the Brooklyn Historic Railway Association. Many of these cars lasted a long time because they were made of stainless steel. This helped protect them from corrosion caused by the salt used to de-ice roads in the Twin Cities winters.

Historical Reminders

Other signs of the company's streetcar history can still be found in the Twin Cities. Some surviving buildings are now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. One of the oldest is a building in Minneapolis called the Colonial Warehouse. Built in 1885, it was the main office for the Minneapolis Street Railway Co. during the horsecar days. It also later became a power station when the system switched to electricity. The streetcar lines needed a lot of power, so hydroelectric generators were built at Saint Anthony Falls and the Southeast Steam Plant was also constructed nearby. The old headquarters was sold in 1908. The University of Minnesota now owns the steam plant and uses it to heat its campus.

A large building on Snelling Avenue in St. Paul was the main shop for building and repairing streetcars when it was built in 1907. It was expanded over the years and later became a big garage for the bus system. However, the building became old and had problems like a leaky roof. It was finally closed and torn down in September 2001.

Selby Hill in St. Paul was a very steep climb. Cable cars were used there in the late 1800s before the Selby Hill Tunnel was built in 1905. The tunnel made the incline more gradual. The tunnel still exists today, but its ends are blocked off. It is near the Cathedral of St. Paul.

Billboards around the area were originally placed to advertise to people riding the streetcars. Many of these billboards stayed for decades, even though cars often used different routes. These billboards finally disappeared in the 1990s due to city efforts to make the area look nicer.

Streetcar Legacy in the 21st Century

In the 1970s, the bus lines were taken over by a public agency called the Metropolitan Council. This agency eventually became Metro Transit, which now manages all regional transportation. Twenty years after streetcars disappeared from the Twin Cities, leaders and planners started suggesting new light rail systems. Traffic was so bad in 1972 that there were ideas for new subways, but they were too expensive.

Rail transport returned to the Twin Cities with the building of the Blue Line, which started running in 2004. There has been talk of a heritage streetcar line that might use some of the old PCC cars once owned by TCRT. A Northstar commuter rail line, which runs northwest out of Minneapolis, opened in 2009. A connection between Minneapolis and St. Paul, called the Green Line, opened on June 14, 2014. As of 2020, a light rail line is being built from Minneapolis to the southwest suburbs. Other ideas include adding commuter rail connections to the north and southeast of downtown St. Paul.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |