Walter E. Williams facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Walter E. Williams

|

|

|---|---|

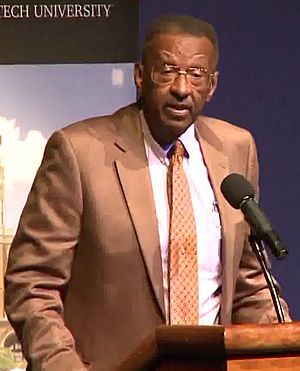

Williams speaking at Texas Tech University in 2013

|

|

| Born |

Walter Edward Williams

March 31, 1936 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Died | December 1, 2020 (aged 84) Fairfax, Virginia, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse(s) |

Connie Taylor

(m. 1960; died 2007) |

| Institution | George Mason University Temple University Los Angeles City College California State University, Los Angeles Grove City College |

| Field | Economics, education, politics, free market, race relations, liberty |

| School or tradition |

Laissez-faire |

| Alma mater | California State University, Los Angeles (BA) University of California, Los Angeles (MA, PhD) |

| Contributions | Analysis of Davis–Bacon Act Research on occupational licensing, specifically in the taxi industry |

Walter Edward Williams (born March 31, 1936 – died December 1, 2020) was an American economist, writer, and professor. He was a well-known professor of economics at George Mason University. Williams also wrote articles for newspapers and magazines and was an author. He was famous for his ideas about classical liberalism and libertarianism, which focus on individual freedom and limited government. His writings often appeared in Townhall, WND, and Jewish World Review. Williams was also a popular guest host for the Rush Limbaugh radio show.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Walter Williams was born in Philadelphia on March 31, 1936. He grew up with his mother and sister. His father was not involved in raising them. His family first lived in West Philadelphia, then moved to North Philadelphia when he was ten. They lived in the Richard Allen housing projects. Famous comedian Bill Cosby was one of his neighbors. Williams knew many of the people Cosby talked about from his childhood.

After finishing Benjamin Franklin High School, Williams went to California. He lived with his father and studied at Los Angeles City College for one semester. He then went back to Philadelphia and worked as a cab driver. In 1959, he joined the United States Army.

While serving in the South, Williams fought against Jim Crow rules within the army. These were laws that enforced racial segregation and discrimination. He challenged the unfair system by speaking out to other soldiers. This led to an officer trying to have him court-martialed, which is like a trial in the military. Williams defended himself and was found not guilty. Later, he was sent to Korea. There, he jokingly marked "Caucasian" for his race on a form. When asked why, he said that if he marked "Black," he would get all the worst jobs.

He received a thoughtful reply from a high-ranking defense official, which he called "the most reasonable response."

After leaving the military, Williams worked with young people for the Los Angeles County Probation Department from 1963 to 1967. He also went back to school. He earned a bachelor's degree in economics in 1965 from California State College at Los Angeles (now Cal State Los Angeles). He then earned both his master's degree and his PhD in economics from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). His PhD paper was about how low-income markets work.

Williams said that when he started college, he was a "radical." He felt more connected to Malcolm X than Martin Luther King. He thought Malcolm X was more willing to fight discrimination, even with violence. At first, he believed laws like minimum wage helped poor people. But his professors at UCLA, like Armen Alchian and James M. Buchanan, made him look at the facts. This changed his mind.

While at UCLA, Williams met Thomas Sowell, another famous economist. They became good friends. In 1972, Williams joined Sowell at the Urban Institute's Ethnic Minorities Project. Their friendship is mentioned in Sowell's 2007 book, "A Man of Letters."

Academic Career

While studying for his PhD, Williams taught economics at Los Angeles City College from 1967 to 1969. He also taught at Cal State Los Angeles from 1967 to 1971.

In 1973, Williams returned to Philadelphia and taught economics at Temple University until 1980. For one year, from 1975 to 1976, he was a visiting scholar at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. In 1980, Williams joined the economics department at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. That same year, he started writing a newspaper column called "A Minority View." He wrote for Heritage Features Syndicate, which later joined with Creators Syndicate. From 1995 to 2001, Williams was the head of the economics department at George Mason. He taught courses like "Intermediate Microeconomics" to college students. He continued teaching at George Mason until he passed away in 2020.

During his nearly fifty-year career, Williams wrote many research papers and book reviews. These appeared in important academic journals like American Economic Review and Journal of Labor Research. He also wrote for popular magazines such as Newsweek and The Wall Street Journal.

Williams received an honorary degree from Universidad Francisco Marroquín. He also served on important advisory boards, including for the National Science Foundation and the Hoover Institute.

Williams wrote ten books. His first books, The State Against Blacks and America: A Minority Viewpoint, came out in 1982. He also wrote and hosted documentaries for PBS in 1985. His documentary "Good Intentions" was based on his book The State Against Blacks.

Economic and Political Views

As an economist, Walter Williams strongly supported free market economics. This means he believed that businesses and people should be mostly free to make their own choices without much government control. He was against socialist systems where the government has a lot of control. Williams believed that laissez-faire capitalism (a system with very little government interference) was the best and most productive way for people to live.

In the 1970s, Williams studied the Davis–Bacon Act of 1931 and how minimum wage laws affected jobs for minority groups. He concluded that government programs that interfere with the economy can actually cause harm. Williams was critical of government programs like minimum wage and affirmative action. He believed these laws limited people's freedom and actually hurt the very people they were meant to help, especially Black Americans. In his 1982 book The State Against Blacks, he argued that laws controlling economic activity were bigger problems for Black people's economic success than racism itself. He often said that raising the minimum wage makes it harder for people with fewer skills to find jobs.

Williams believed that the problems of racism and the history of slavery in the United States are sometimes overemphasized today. He thought that the negative effects of the welfare state (government help programs) and the breakdown of the Black family were more serious issues. He famously said, "The welfare state has done to black Americans what slavery couldn't do, and that is to destroy the black family." While he supported equal access to public places like courthouses and libraries, Williams was against anti-discrimination laws for private businesses. He felt these laws took away people's right to choose who they associate with, which he called freedom of association.

Williams saw gun control laws as the government limiting individual rights. He argued that these laws often put innocent people in danger and do not stop crime. He also believed that if you truly own something, you should have the right to sell it. Following this idea, he supported the legalization of selling one's own bodily organs. He argued that the government stopping people from selling their organs was a violation of their property rights.

Williams admired the ideas of Thomas DiLorenzo. He even wrote the introduction for DiLorenzo's book, The Real Lincoln, which had a critical view of Abraham Lincoln. Williams believed that American states should have the right to leave the union if they wanted to. He said that the Union's victory in the Civil War allowed the federal government to gain too much power. He felt this weakened the protections of states' rights that are in the Ninth and Tenth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution.

Williams was also against the Federal Reserve System, which is the central bank of the United States. He argued that central banks are dangerous.

In his own life story, Williams said that thinkers like Frédéric Bastiat, Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, and Milton Friedman helped him become a libertarian. He praised Ayn Rand's book Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal as a great explanation and defense of capitalism.

Besides writing his weekly articles, Williams often filled in as a guest host for Rush Limbaugh's radio show when Limbaugh was away. In 2009, a writer named Greg Ransom ranked Williams as one of the most important "Hayekian" public thinkers in America. Reason magazine called Williams "one of the country's leading libertarian voices."

Personal Life and Death

Walter Williams lived in Devon, Pennsylvania, since 1973. He was married to Connie Taylor from 1960 until she passed away in 2007. They had one daughter named Devyn. When he started teaching at George Mason University, he would rent a hotel room in Fairfax, Virginia, from Tuesdays through Thursdays to be close to his classes. Williams was also a cousin of the famous former NBA player Julius Erving.

Williams served on the board of directors for Media General, which owned the Richmond Times-Dispatch newspaper. He was on the board from 2001 until he retired in 2011. He was also the chairman of the company's audit committee.

Walter Williams died in his car on December 1, 2020, at the age of 84. This happened shortly after he taught a class at George Mason University. His daughter said he had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypertension (high blood pressure). Before he died, Williams was in a documentary called Uncle Tom. In the film, he shared his thoughts on conservatism within the Black community and talked about his own views as a Black conservative.

Filmography

- (1982), a documentary based on Williams' book The State Against Blacks.

See also

In Spanish: Walter E. Williams para niños

In Spanish: Walter E. Williams para niños

- Black conservatism in the United States

- Libertarian conservatism

- List of economists

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |