Walter Munk facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Walter Munk

|

|

|---|---|

Munk in 1956.

|

|

| Born |

Walter Heinrich Munk

October 19, 1917 |

| Died | February 8, 2019 (aged 101) La Jolla, California, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Columbia University California Institute of Technology (BS, MS) Scripps Institution of Oceanography/University of California, Los Angeles (PhD) |

| Awards | Maurice Ewing Medal (1976) Alexander Agassiz Medal (1976) National Medal of Science (1985) Bakerian Lecture (1986) William Bowie Medal (1989) Vetlesen Prize (1993) Kyoto Prize (1999) Prince Albert I Medal (2001) Crafoord Prize (2010) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Oceanography, geophysics |

| Thesis | Increase in the period of waves traveling over large distances : with applications to tsunamis, swell, and seismic surface waves (1946) |

| Doctoral advisor | Harald Ulrik Sverdrup |

| Doctoral students | Charles Shipley Cox, June Pattullo |

Walter Munk (born October 19, 1917, died February 8, 2019) was an amazing American scientist. He studied the ocean, a field called physical oceanography. He was one of the first scientists to use math and statistics to understand ocean data.

Walter Munk won many important awards for his work. These included the National Medal of Science and the Kyoto Prize. He was also honored by France with the Legion of Honour.

Munk studied many different things about the ocean and Earth. He looked at surface waves, how the Earth's spin changes, tides, and waves deep inside the ocean. He also studied sea level rise and climate change.

In 1975, Munk and another scientist, Carl Wunsch, started using sound to measure the ocean. This method is called ocean acoustic tomography. Sound travels easily in water, so they used it to measure ocean temperature and currents over large areas.

In 1991, Munk and his team tried an experiment. They sent sound from the southern Indian Ocean across all the world's oceans. Their goal was to measure the global ocean temperature. Some environmental groups worried the loud sounds might harm sea animals. But Munk kept working on and supporting sound-based ocean measurements throughout his life.

Walter Munk's career began before World War II and lasted almost 80 years. The war paused his studies at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. But it also led him to help the U.S. military. Munk and his teacher, Harald Sverdrup, created ways to predict ocean waves. These predictions helped soldiers land safely on beaches during the war. He also helped with ocean studies during the atomic bomb tests in Bikini Atoll.

For most of his career, Munk was a professor at Scripps. This is part of the University of California, San Diego in La Jolla, California. Munk and his wife, Judy, also helped build up the Scripps campus. Munk was also part of a science group called JASON. He held a special oceanography position with the U.S. Navy.

Contents

Walter Munk's Early Life and School

Walter Munk was born in Vienna, Austria-Hungary, in 1917. His family was Jewish. When he was ten, his parents divorced. His grandfather was a famous banker and politician. His stepfather worked for the Austrian government.

In 1932, Walter was not doing well in school because he loved skiing too much. So, his family sent him to a special school in New York. They wanted him to work in banking, like their family business. He worked at the bank for three years and studied at Columbia University.

But Walter did not like banking at all. In 1937, he left the bank to go to the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). While at Caltech, he got a summer job in 1939 at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California.

Munk earned his first degree in physics in 1939. He got his master's degree in geophysics in 1940 from Caltech. His master's work used ocean data collected by a Norwegian oceanographer, Harald Sverdrup. Sverdrup was the director of Scripps at the time.

In 1939, Munk asked Sverdrup to be his teacher for his PhD. Sverdrup agreed, even though he thought there would be no jobs in oceanography. Munk's studies were stopped by World War II. He finished his PhD in oceanography at Scripps in 1947. He wrote his paper in just three weeks!

Walter Munk's Work During World War II

In 1940, Walter Munk joined the U.S. Army. This was unusual for a student at Scripps. Most others joined the Navy. After 18 months, he was released from the Army. This was so he could do important defense research at Scripps.

In December 1941, Munk joined other scientists at a U.S. Navy lab. For six years, they worked on ways to fight submarines and plan beach landings. This research involved studying sound in the ocean. It later led to his work on ocean acoustic tomography.

Predicting Ocean Waves for Allied Landings

In 1943, Munk and Sverdrup started looking for a way to predict how high ocean waves would be. The Allies were getting ready to land in North Africa. Waves there were often very high, making landings dangerous.

Munk and Sverdrup found a way to link wave height and time to wind speed and how long and far the wind blew. The Allies used this method in the Pacific Ocean and for the Normandy invasion on D-Day. People at the time believed these predictions saved many lives.

Ocean Studies During Atomic Bomb Tests

In 1946, the United States tested two atomic bombs at Bikini Atoll. This is in the Pacific Ocean. Munk helped figure out how ocean currents would spread radiation from the second test.

Six years later, he went back to the Pacific for the 1952 test of the first hydrogen bomb. Munk and other scientists started a program to watch for a large tsunami from the test.

Later Work with the Military

Munk stayed connected with the military for many years. He was one of the first scientists to get money for research from the Office of Naval Research. He received his last grant from them when he was 97 years old.

In 1968, he joined JASON. This is a group of scientists who advise the Pentagon. He stayed with them until he died. He also held a special oceanography position with the U.S. Navy from 1985 until 2019.

Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics

After getting his PhD in 1947, Munk became a professor at Scripps. In 1954, he became a full professor. In 1955, Munk visited Cambridge, England. His time there gave him the idea to start a new science branch at Scripps. This branch would be for geophysics.

Scripps became part of the new University of California, San Diego (UCSD) in 1958. Munk helped create the new campus. He turned down job offers from other famous universities to stay in La Jolla. He then started the Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics (IGPP) at Scripps.

The IGPP building was built between 1959 and 1963. Walter and his wife, Judith Munk, worked closely with the architect on its design. The IGPP buildings became the main part of the Scripps campus. Many famous scientists worked there. Munk was the director of IGPP from 1962 to 1982.

Later, the IGPP expanded. In 1993, the Revelle Laboratory was finished. The original IGPP building was renamed the Walter and Judith Munk Laboratory for Geophysics.

Walter Munk's Discoveries

Walter Munk's work in oceanography and geophysics covered many new and exciting topics. He often started a completely new area of study. He would ask big, important questions about it. Then, after creating a whole new science field, he would move on to another new topic.

Ocean Gyres and Wind

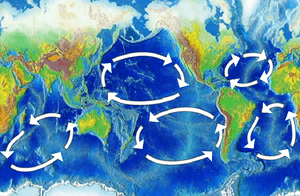

In 1948, Munk studied how winds create ocean currents. He found the first full solution for currents based on how winds blow. His model showed the five main ocean gyres. These are like giant, slow whirlpools in the ocean.

His model predicted fast, narrow currents on the west sides of oceans. These flow towards the poles. It also showed wider, slower currents on the east sides, flowing away from the poles. Munk invented the term "ocean gyres," which scientists still use today.

How the Earth Rotates

In the 1950s, Munk looked at how the Earth's spin changes. He studied changes in the length of a day. He also looked at how the Earth's axis of rotation moves, like a wobbling top.

In 1960, Munk published a book about the Earth's rotation. It explained that short-term changes are caused by movements in the atmosphere, ocean, and inside the Earth. Over longer times, like centuries, the Moon's pull slows the Earth's spin. This makes the day slowly get longer.

Project Mohole: Drilling into Earth

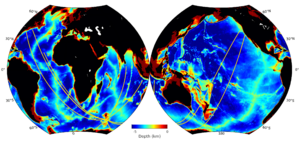

In 1957, Munk and Harry Hess had an idea called Project Mohole. They wanted to drill deep into the Earth's crust to reach the mantle. The mantle is a layer inside the Earth. Drilling in the ocean would be easier because the mantle is closer to the sea floor there.

The project started with test drillings in 1961. However, it became too expensive and was stopped by Congress. Even though Project Mohole didn't succeed, its idea led to another successful project. This was the Deep Sea Drilling Program, which collected samples from the ocean floor.

Ocean Swell: Waves Across the Pacific

In the late 1950s, Munk went back to studying ocean waves. He used new math methods to describe how waves behave. In 1963, he led an expedition called "Waves Across the Pacific." They watched waves created by storms in the Southern Indian Ocean. These waves traveled thousands of miles across the Pacific Ocean.

Munk set up stations on islands and at sea to track the waves. He and his family even lived on American Samoa for nearly a year for this experiment. The results showed that wave energy didn't decrease much over long distances. This work, along with his wartime research, led to the science of surf forecasting. This is one of Munk's most famous achievements.

Ocean Tides

From 1965 to 1975, Munk studied ocean tides. He used modern math tools to analyze tides. He also worked with Frank Snodgrass to create special sensors. These sensors could measure tides far out in the deep ocean. One exciting discovery was finding a special point in the ocean where tides seem to disappear. This point was between California and Hawaii.

Internal Waves: The Garrett–Munk Spectrum

Internal waves are waves that move inside the ocean, not on the surface. By the 1970s, scientists had many observations of these waves. Munk and Chris Garrett tried to make sense of all this data. They created a universal model for internal waves, now called the Garrett-Munk Spectrum.

This model helps explain how internal waves behave all over the world. Even though Munk thought it would quickly become old, it is still used today. It shows that there are important processes controlling how internal waves move and mix the ocean.

Ocean Acoustic Tomography

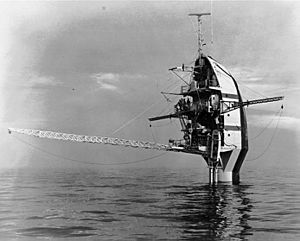

Starting in 1975, Munk and Carl Wunsch began using sound to study the ocean. This method is called acoustic tomography. They used how sound travels and how long it takes to arrive to learn about the ocean's temperature and currents.

This work led to the 1991 "Heard Island Feasibility Test." The goal was to see if human-made sounds could travel across the entire ocean. The experiment was called "the sound heard around the world." For six days, sounds were sent from Heard Island in the Indian Ocean. These sounds traveled halfway around the globe. They were heard on the coasts of the United States and other places.

A later project, from 1996 to 2006, used this method in the North Pacific. Both experiments caused some public debate. People worried about how the sounds might affect marine mammals. But acoustic tomography has become a very useful way to observe the ocean. It helps scientists measure average ocean temperature and currents over large areas.

Munk believed in using sound to study the ocean for most of his career. He gave many talks and wrote books about it.

Tides and Ocean Mixing

In the 1990s, Munk returned to studying how tides help mix the ocean. In a paper from 1966, he was one of the first to measure how much mixing happens in the deep ocean. This mixing helps keep the ocean layered with warm water on top and cold water below.

Scientists later discovered that large internal tides send energy away from underwater mountains. Munk realized that this tidal energy could cause mixing in the deep ocean.

Munk's Enigma

In his later work, Munk focused on how ocean temperature, sea level, and melting ice affect each other. He described something called "Munk's enigma." This was a big difference between how fast sea level was rising and how that rise should affect the Earth's spin.

Awards and Honors

Walter Munk was chosen to be a member of many important science groups. These included the National Academy of Sciences in 1956 and the Royal Society of London in 1976. He also received special fellowships to support his research. In 1969, he was named California Scientist of the Year.

In July 2018, when he was 100 years old, Munk received a special honor from France. He was made a Chevalier of France's Legion of Honour for his great work in oceanography.

Munk received many other awards, including:

- The Maurice Ewing Medal in 1976

- The Alexander Agassiz Medal in 1976

- The National Medal of Science in 1983

- The William Bowie Medal in 1989

- The Vetlesen Prize in 1993

- The Kyoto Prize in 1999

- The Prince Albert I Medal in 2001

- The Crafoord Prize in 2010 for his work on ocean currents, tides, and waves.

In 1993, Munk was the first person to receive the Walter Munk Award. This award honored his excellent research using sound to study the ocean. Later, this award was changed to the Walter Munk Medal, covering more topics in oceanography.

Two ocean animals were named after Walter Munk. One is a deep-sea worm called Sirsoe munki. The other is Mobula munkiana, also known as Munk's devil ray. This ray is a small relative of giant manta rays. It lives in huge groups and can jump high out of the water. A movie in 2017 followed Munk on a trip to see these rays.

Walter Munk's Personal Life

After Nazi Germany took over Austria in 1938, Munk applied to become a citizen of the United States. He became an American citizen in 1939.

Munk married Martha Chapin in the late 1940s, but they divorced in 1953. On June 20, 1953, he married Judith Horton. Judith was very active at Scripps. She helped with planning the campus and fixing up old buildings. The Munks often traveled together. Judith died in 2006. In 2011, Munk married Mary Coakley.

Walter Munk continued to work on science throughout his life. He published papers as late as 2016. He turned 100 years old in October 2017. He died from pneumonia on February 8, 2019, in La Jolla, California, at the age of 101.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |