Women in the California Gold Rush facts for kids

The California Gold Rush began in Northern California in 1848. At first, the women living there included Spanish descendants called Californios, Native American women, and new immigrants from all over the world. There weren't many immigrant women at first, but they still helped their communities.

Some of the first people in the mining fields were wives and families already living in California. A few settler women and children worked alongside the men. However, most men who arrived left their wives and families at home. The number of women in California changed quickly. The rich gold discoveries and the lack of women created a strong need for more women in the new Gold Rush towns.

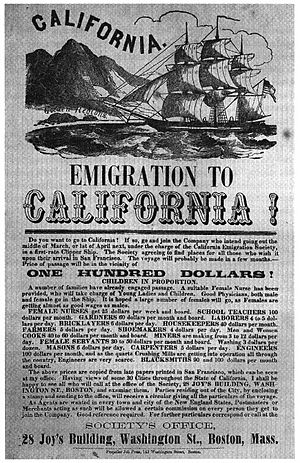

As travel became easier, more women came to California. Many probably traveled through Panama. This was one of the fastest trips, taking 40 to 90 days. It was also reliable, though expensive in 1850. The cost was about $400-$600 per person for a one-way trip. Travel through Panama became much more dependable after paddle wheel steamship lines started running by late 1849. In Ireland, the Great Famine (1845-1852) caused many desperate women to move to the United States and then to California.

Women from many different places and backgrounds were part of the California Gold Rush. The fast-growing population had very few women. Because of this, women found many new chances to work. As news of the gold rush spread, so did the news of opportunities for women in the goldfields and towns.

Many women came to California to join their families. Miners or businessmen who decided to live in California usually paid for their passage. Most men had planned to find gold, then return home rich. Women who worked as entertainers often had no money for the trip. But once they arrived in California, saloons, gambling halls, and dance halls hired them. Their travel costs were usually paid if they agreed to work for three to six months. These entertainers were the majority of women at first. Few of them made the long trip by wagon on the California Trail or the even longer sea journey around Cape Horn.

As gold mining and related businesses grew, many men decided to stay in California. Husbands or future husbands sent money home for their women and families to join them. Others went back east to finish their business and bring their families to California. Many single men wrote to female friends they knew. Many marriage proposals were accepted through these long-distance letters. A letter from California to the east could take 60 days to arrive, and a reply another 40-60 days. This was a very "slow" way to court someone! If a proposal was accepted, the successful miner or businessman sent money for the woman's trip. Often, as soon as the future bride got off the ship, she was rushed to a preacher to get married. Most single women in California quickly received several marriage proposals. Over time, more women and families arrived, changing the female population. Soon, entertainers were no longer the largest group of women.

There were many chances for women in the cities and goldfields. Men, who missed female company, paid a lot of money to be around women or to buy things women made. There are stories of women earning more money selling homemade pies or doughnuts than their husbands made mining. Laundries, restaurants, lodging, mending clothes, and waiting tables all paid well. Some women became rich as business owners.

A small number of other women (less than 3% of early travelers) came with their husbands and families. They traveled either overland on the California Trail or by sea. They did not want to be left behind or miss an exciting chance to change their lives. A few of these women became widows because their husbands died from disease or accidents. On the California Trail, about 4% of travelers died from accidents, cholera, fever, and other causes. Many women became widows before even reaching California. The sea voyage through Panama also had dangers. Crossing the Isthmus of Panama by canoe and mule was risky. Waiting in disease-filled Chagres and Panama City was dangerous. Cholera and yellow fever often killed many people, sometimes up to 30% of a group. The last step was a 15- to 20-day trip to California on a paddle wheel steamship.

The number of men was much higher than the number of women in California for many years. It took several generations for the numbers to become more equal.

Contents

Number of Women in California

| California Population (in thousands) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | Male | Female |

|

|

|||

| 18401 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| 18502 | 120 | 110 | 10 |

| 18523 | 200 | 180 | 20 |

| 1860 | 380 | 273 | 107 |

| 1870 | 560 | 349 | 211 |

| 1880 | 865 | 518 | 347 |

| 1890 | 1,213 | 703 | 511 |

| 1900 | 1,485 | 821 | 665 |

| 1910 | 2,378 | 1,323 | 1,055 |

| 1920 | 3,431 | 1,814 | 1,613 |

| 1930 | 5,677 | 2,943 | 2,735 |

| 1940 | 6,907 | 3,516 | 3,392 |

| 1950 | 10,586 | 5,296 | 5,291 |

|

|

|||

| 1) Californios found in 1850 U.S. Census | |||

| 2) 1850 Census Adjusted for missing data | |||

| 3) 1852 California State Census | |||

| California Historical U. S. Census Data | |||

|

|

|||

The first U.S. California Census in 1850 counted all non-Indian people. It showed about 7,019 females in the state. About 4,165 of these non-Indian females were older than 15. We should also add about 1,300 women over 15 from San Francisco, Santa Clara, and Contra Costa counties. Their census records were lost. This means there were about 5,500 females older than 15 in California in 1850. The total non-Indian population was about 120,000 residents. So, only about 4.5% of the population was female.

To estimate the number of women in mining areas, we can subtract the roughly 2,000 females who lived in mostly Californio communities. These communities were not part of the Gold Rush. This means about 3.0% of the Gold Rush travelers before 1850 were female. That's about 3,500 female Gold Rushers compared to about 115,000 male Gold Rushers.

By California's 1852 State Census, the population had grown to about 200,000. About 10% of these, or 20,000, were female. By 1852, competition had lowered the steamship fare through Panama to about $200. The Panama Railroad (finished in 1855) was also being built across the Isthmus. This made it even easier to get to California.

By the 1860 U.S. Federal Census, California had a population of 330,000. There were 223,000 males and 107,000 females. This was still more than 2 males for every 1 female. By 1870, the population grew to 560,000. There were 349,000 males and 211,000 females. This was a ratio of 100 males to 38 females. The number of females and males finally became almost equal by the 1950 census. At that time, the total population was 10,586,000. There were 5,296,000 males and 5,291,000 females.

First Women to Arrive

Women from many different backgrounds came to the California Gold Rush. California's population was growing fast, but it had very few women. This meant women found many new chances that were not usually available to them. As news of the gold rush spread, so did the news of job opportunities for women in the goldfields and towns that needed them.

Some of the first women to arrive were from southern California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Acapulco, and San Blas. Since women from Sonora were the most common, miners often called all of them 'Sonorans' or 'Senoritas'. Soon, women from Panama, Ecuador, Peru, and Chile also joined them. Because Chileans were the most common, all South American Latinos were often called 'Chilenos'. As news of job opportunities for women reached the east coast, and travel plans became more reliable with paddle wheel steamship lines on the Caribbean and Pacific Ocean, many more women started coming to California.

Life in Gold Rush Towns

In San Francisco, a main port for ships and passengers, the population exploded. It grew from about 200 people in 1846 to 36,000 in 1852. At first, many women and men in San Francisco lived in wooden houses, ships pulled onto the shore, canvas tents with wood frames, and other buildings that could easily catch fire. These types of buildings, combined with many drunken gamblers and miners, often led to fires. Most of San Francisco burned down six times in six "Great Fires" between 1849 and 1852. From San Francisco, by late 1849, paddle steamers were taking miners and others about 125 miles (201 km) to Sacramento. This was the starting point for the California Gold Rush country.

Jobs for Women

A few women came to California with their husbands and children. They often helped pan for gold or earned money while their husbands tried to find gold. Others came on their own specifically to mine for gold. One Mexican woman reportedly brought several workers to the mines to pan gold for her. Another woman made over $2,000 in just 46 days of mining.

One very popular way for women to earn a living was to run a boarding house. The writer Mary Ballou did this. Another popular job was cooking or running a restaurant. California was one of the only places where women could earn higher wages than men for the same work. This was because women were scarce. Men would pay a lot just to have women around and to do household tasks they didn't want to do or didn't know how to do. One clever woman earned $18,000 by baking pies.

Washing clothes was another job women did. At first, most washerwomen were Native American or Mexican women. When white men saw how much money could be made, they also started doing laundry. A pond in San Francisco called "Washerwoman's Bay" became a popular place for women doing laundry to gather. Laundry workers even held a meeting in 1850 to talk about prices and form a group. However, by 1853, Chinese male immigrants had taken over much of the laundry business.

Some women and girls, like Lola Montez and Lotta Crabtree, became successful dancers and actors. Montez came to San Francisco after performing in Europe. Lotta Crabtree, whose parents were Gold Rush immigrants, started her career dancing for miners when she was only six years old.

Most single women came as part of a family or as an entertainer. Many men did not find their fortune in the goldfields. Having a woman around to earn money by running a boarding house, washing, cooking, or sewing could make a big difference for a family's well-being. A few women had their own gold mining claims. They came west specifically to pan for gold. As the easy-to-find placer gold became harder to find, and mining became more complicated, women usually moved out of the goldfields and into other types of work. Most women received many marriage proposals and could get married very quickly if they found someone they liked.

For some women, the Gold Rush created economic and career chances they didn't have back home. Julia Shannon and Julia Randolph became well-known professional studio photographers. This was a new field that was relatively easy for women to enter, though men still mostly ran it. Eleanor Dumont, also known as Madame Moustache, earned her living as a card shark, moving from town to town. She eventually opened her own gambling parlor. The businesswoman Mary Ellen Pleasant, who called herself a "capitalist," used her wealth to help free slaves through the Underground Railroad. Other women worked as barbers, nurses, schoolteachers, mule packers, and circus performers. Charlotte Parkhurst dressed as a man and drove a stagecoach. One woman managed a theater, and another managed a bowling alley. One woman wrote about seeing a "lady bullfighter."

In the mines in the Sierra Nevadas, where there were fewer white women, Mexican and Chilean women became more important. This was because more competition caused them to leave the larger towns and cities and go to the smaller gold mining camps. This chance for economic improvement was easier for non-white women than for non-white men.

Writers and Journalists

Some women wrote letters home, kept diaries, or wrote newspaper articles about their experiences during the Gold Rush. Later historians collected and published these writings. They offer a look into their journeys west and life at that time. One famous work is The Shirley Letters, by Louise Amelia Knapp Smith Clappe. Other writers include Luzena Wilson, Mary Jane Megquier, Sallie Hester, and Eliza Farnham. Jennie Carter wrote for the African-American California newspaper The Elevator during the 1860s and 1870s.

Marriage in the Gold Rush

Because there were so few women in Gold Rush California, the marriage market favored them. While parents' approval and money concerns sometimes played a role in engagements, they became less important. Marriages between people of different backgrounds, though still sometimes looked down upon, were more common in California. This was because white women were a small minority among the diverse group of women.

Women also found it easier to get a divorce in California than in other places. Judges seemed to want to increase the number of women available for marriage. As divorced women, they did not face the negative public judgment sometimes seen elsewhere. Divorce was often part of the new Californian culture. Women who were available for marriage usually received several proposals in a short time.

Starting in the mid-1850s, people began to settle into more traditional roles and ways of life. They moved away from non-traditional gender roles. Many single men sent for their families. Middle-class American values became more common as the number of middle-class wives and families grew. It's thought that about 30% of the male miners were married men who had left their families to try their luck in California. Many men went back home, but many others brought their families to California and stayed. The arrival of more white women, who were often seen as symbols of purity and good behavior in the Victorian era, often changed what was considered "accepted" behavior and values. In some communities with many non-white immigrants, some non-white male groups were given jobs that were once seen as "feminine" (for example, Chinese men doing laundry and cooking).

Property Rights for Women

Delegates at the 1849 California Constitutional Convention discussed and adopted California's first constitution. It stated that "All property, both real and personal, of the wife, owned or claimed by her before marriage, and that acquired afterwards by gift, devise, or descent, would remain her separate property." This meant that a wife's property, whether she owned it before marriage or received it as a gift or inheritance afterward, would stay hers alone.

Delegates gave different reasons for this rule. Some said it reflected the existing law in California and other states. The wording of the proposal was taken almost word for word from the Texas constitution. This showed the influence of civil law traditions from French or Spanish legal systems. In contrast, the English-based common law used in many American places at the time gave women few or no property rights after marriage. They usually only had rights to one-third of household goods and land if their husband died.

There were arguments for and against this rule. A delegate from New York warned against giving women separate property rights. He based his warning on his experiences in France. He argued that such rights led to "domestic disunion." He said that there, husband and wife were business partners, making the wife like a partner instead of just a head clerk. He felt this idea went against nature and marriage.

One delegate who supported the rule said, "We are told, Mr. Chairman, that woman is a frail being; that she is formed by nature to obey, and ought to be protected by her husband, who is her natural protector. That is true, sir; but is there any thing in all this to impair her right of property which she possessed previous to entering into the marriage contract? I contend not." Another argued that it would empower women and attract them to California, where marriageable Anglo-American women were scarce. He said, "Having some hopes that I may be wedded...I shall advocate this section in the Constitution, and I will call upon all the bachelors in this convention to vote for it. I do not think that we can offer a greater inducement for women of fortune to come to California. It is the very best provision to get us wives that we can introduce into the Constitution."

While people understood this constitutional rule in different ways, scholar Donna C. Schuele says that it was seen as a forward-thinking law. It made California stand out from eastern states that still held onto old ideas about law and male control. However, in 1850, the California State Legislature passed property laws that weakened some parts of this constitutional promise. One law said that the husband had control over his wife's separate property. But he could not sell or put a lien on the property without his wife's written consent, given when her husband was not present. California also adopted community property laws when it became a state. These laws gave each spouse a right to half of whatever was gained during the marriage.

Native American Women

In the early days of the Gold Rush, the Native people of California, including women, also panned for gold. Some were quite successful. Gold had no trade value in their cultures, but they understood its value to the new arrivals. The men would dig and pass the mud to the children. The children then carried it in baskets to the women. The women, lined up along the stream, washed the mud in grass baskets, taking out the gold.

However, as more and more immigrants arrived, conflicts between the newcomers and Native peoples grew. The killing, forced movement, and enslavement of Native Americans became official California policy. Women were sometimes attacked and kidnapped to be sold into slavery, along with their children. In one event, an old chief surrounded himself with women while under attack by white men. He told the women they were safe because he did not believe the whites would kill women. The chief and all the women lost their lives.

The newcomers also brought diseases and caused starvation by using up natural resources. In 1850, California passed a law that allowed white people to enslave Native Americans who were found orphaned or "loitering." The enslavement of Native people had already been started by the Spaniards and Californios before the Gold Rush. After the Gold Rush, rewards were offered to "Indian hunters" who could prove they had killed a Native person by bringing in a body part. The Native American population of California dropped from 150,000 in 1848 (when gold was discovered) to 30,000 in 1870. Some Native Americans were able to avoid being killed by pretending to be Mexican. Stories of massacres, forced relocation, and kidnappings have been passed down through generations, often by women. California Native people still remember these stories today.

Images for kids