Jennie Carter facts for kids

Jennie Carter (born around 1830 – died August 1881) was an American journalist and writer. She wrote for The Elevator, an African-American newspaper in California. She wrote from her home in Nevada County during the time after the Civil War, known as the Reconstruction Era. Jennie Carter used the pen names Anna J. Trask and later Semper Fidelis. Her writings covered many topics, like slavery, racism, women's rights, and politics. Her work was read by many black communities in the American West and across the country in the late 1800s. Today, her essays are being published again, and more people are learning about her important work.

Contents

Early Life and Experiences

Records show that Jennie Carter was born in either New York City or New Orleans around 1830 or 1831. She was born a free person of color, meaning she was not enslaved. She likely spent her early years in New Orleans and New York. Later, she lived in Kentucky and Wisconsin. Her mother died when she was young, so her grandmother raised her.

In her essays, Jennie described a middle-class childhood. She loved to read and was "passionately fond of music." She wrote about playing with her dolls in the attic at age fourteen. She also had a younger sister who sadly died at age ten from a spinal disease. Jennie later wrote about how bad she felt because she had hit her sister a few weeks before she died. She used this story to teach her young readers to avoid anger.

Jennie Carter shared a helpful tip from an old man: "Keep the head cool and calm. Second, keep the feet dry and warm. Third, keep the heart free from anger." She said these tips helped her stay healthy.

Jennie saw the harsh reality of slavery many times. As a child, she watched a young friend taken away from his mother by slave masters. In 1850, while living near Hazel Green, Wisconsin, a young woman fleeing slavery arrived at her home with her baby. Jennie hid the woman in her cellar. Then, she drove her by buggy to a Quaker "safe house" nearby. This helped the woman escape to freedom. In another story, a man who escaped slavery showed up at her door. Jennie helped raise money in her community for him to continue his journey to freedom.

Before she became a writer, Jennie Carter worked as a teacher and a governess.

Life and Writing in Nevada County

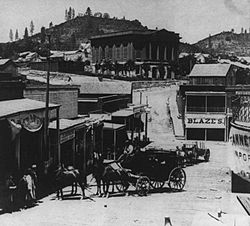

Around 1860, before the Civil War, Jennie Carter moved to Nevada County. She moved there with her first husband, Reverend Correll. Nevada County is in the Sierra Nevada mountains. It had small but growing towns like Nevada City and Grass Valley. This area supported the Union during the Civil War. About 150-300 African Americans lived there, working in many different jobs. Some were active in civil rights and helped organize the California Colored Convention in 1855. While married to the Reverend, Jennie was Vice President of the Grass Valley Christian Commission.

In 1866, she married her second husband, Dennis Drummond Carter. He was a musician and a civil rights activist. They lived in a house full of musical instruments in Nevada City.

In 1867, Jennie Carter wrote to Philip A. Bell, the editor of The Elevator. This was a weekly black newspaper in San Francisco. She offered to write short stories for children. Bell liked her idea. He published her letter and a short essay about her childhood dog in the next issue.

Over the next seven years, Jennie published more than 70 articles in The Elevator. Her topics grew beyond children's stories. She wrote about California and national politics, racism, women's rights, education, and many other issues. She first used the name Mrs. Trask, and later Semper Fidelis. The Elevator was read across the American West. This meant Jennie Carter's work became known regionally and sometimes nationally. She also wrote for the Christian Recorder, a newspaper in Philadelphia.

Jennie Carter sometimes used humor in her writing. She claimed to live in a town called Mud Hill, which she said was "a great deal prettier than its name would signify." She also joked about being sixty years old in her columns, even though she was twenty years younger. She wrote about being a "garrulous" (talkative) old lady who kept "summer in my heart." She said she was "not in the least dignified" and enjoyed skipping rope and playing hide-and-seek with neighbor children. She used her wit to tell important stories through everyday life.

When her articles started to cover more adult topics, she wrote: "Well, Mr. Editor, I see have made a mistake. I commenced writing for the children, and have wound up writing for everybody. May it be excused, with the thousand of others I have made through life."

Jennie Carter's Views

Fighting Racism

Jennie Carter strongly spoke out against racism and colorism (discrimination based on skin color). She wrote: "Children, you hear a great deal said about color by those around you... Such are wrong, and that you may avoid like mistakes I write this for you to read. Let your motto be, civility to all, servility to none." She wanted people to treat everyone with respect, no matter their skin color.

She used stories from her own life and her husband's life to show how they dealt with racism. Once, her husband Dennis was stopped by white men near Harper's Ferry, West Virginia. They told him black people could not travel after 4 PM. Dennis calmly offered to fight anyone who touched him. In another essay, she told how she and her husband were blocked by white men while walking in Nevada City. Jennie used her quick wit to confuse them with a riddle, allowing them to pass.

Women's Rights

Jennie Carter believed women were very important in shaping society. However, she did not support women's suffrage (the right for women to vote) before black men had the right to vote. She criticized white women who were upset that black men could vote while they could not. She felt that politics was not "woman's proper sphere." She believed women had a "higher and more holy mission" and that the rough world of politics would make them "a loser in self respect." She and her editor, Phillip Bell, who supported women's suffrage, often debated this topic in The Elevator.

Travels and Observations

Jennie Carter traveled around Northern California and into Nevada. She wrote about her experiences in San Francisco, Carson City, Nevada City, and Marysville. She felt sad about the lack of sunshine in San Francisco and the divisions within the city's black community. But she found her five weeks in Carson City "invigorating." She noted that "the black people there were doing well, and had pleasant homes."

Current Events

Even though she didn't think women should be politicians, Jennie Carter shared her strong opinions on the politics of her time. She wrote about the ongoing divisions from the Civil War between pro-slavery Democrats and pro-Union Republicans during Reconstruction.

She also spoke out about Chinese immigration, a very debated issue. Many people, both black and white, were trying to keep Chinese immigrants out. Jennie firmly supported the Chinese immigrants. She reminded her readers to "remember those in bonds as being bound to us."

Jennie Carter believed her era was a time of great change. She wrote that the world was "shaking," not just physically but mentally. She felt that slavery and religious intolerance would soon be things of the past. She believed that a person's worth would be based on their mind, not their physical appearance or skin color. She felt lucky to live in such an exciting time and help with its development.

Death and Legacy

Jennie Carter passed away in August 1881 at the age of 51. Her obituary said she died suddenly from "Dropsy of the Heart." She is buried in the Pine Grove Cemetery in Nevada City. Her husband, Dennis Drummond Carter, lived longer than her and was still in Nevada City in 1893.

Jennie Carter's writings are now getting more attention. This is thanks to Eric Gardner's 2007 book, Jennie Carter: A Black Journalist of the Early West. A reviewer noted that her work helps us understand more about black middle-class life in the late 1800s American West. Gardner's research also helped uncover little-known black communities in the Sierra Nevada mountains. These communities were connected to larger cities like Sacramento and San Francisco.

Gardner believes that writings like Carter's, published in black newspapers, were a very important part of African-American literature in the 1800s. He compared her short essays to the work of famous writers like Mark Twain and Bret Harte, who also wrote short essays about the American West. Gardner thought her pen name, Semper Fidelis (meaning "Always Faithful"), showed that for Jennie Carter, writing was an act of faith for her community. It was a way to discuss important topics and encourage people to get involved.

The Nevada County historical society has included Jennie Carter in their exhibit about black pioneers of the Sierra Nevada. Most of these African-American communities disappeared by the 1900s as people moved to bigger cities for jobs. A video reenactment of several of Jennie Carter's essays was filmed at the Doris Foley Historical Library and Pine Grove Cemetery in Nevada City, California.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |