Yuri Orlov facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Yuri Fyodorovich Orlov

|

|

|---|---|

| Юрий Фёдорович Орлов | |

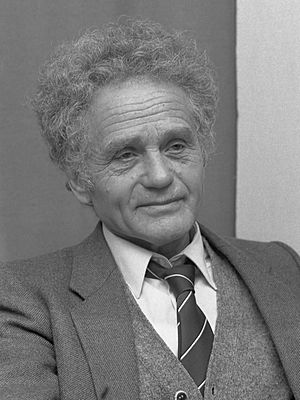

Orlov in 1986

|

|

| Born | 13 August 1924 |

| Died | 27 September 2020 (aged 96) |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | Moscow State University, Institute for Theoretical and Experimental Physics |

| Known for | his scientific work and participation in human rights movement in the Soviet Union |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | sons Dmitri, Aleksandr, Lev |

| Awards | Carter-Menil Human Rights Prize (1986), honorary doctorate Uppsala University (1990) Nicholson Medal for Humanitarian Service (1995), Andrei Sakharov Prize (APS) (2006), Robert R. Wilson Prize for Achievement in the Physics of Particle Accelerators American Physical Society (2020) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Accelerator physics, Nuclear physics |

| Institutions |

|

Yuri Fyodorovich Orlov (Russian: Ю́рий Фёдорович Орло́в, 13 August 1924 – 27 September 2020) was a brilliant scientist and a brave human rights activist. He was a particle accelerator physicist, which means he studied how tiny particles move very fast. He was also a Soviet dissident, someone who spoke out against the government in the Soviet Union.

Yuri Orlov helped start the Moscow Helsinki Group and was a founding member of the Soviet Amnesty International group. These groups worked to protect human rights. Because of his work, he was called a prisoner of conscience. This means he was put in prison for his beliefs, not for committing a crime. He spent nine years in prison and exile for trying to make sure the Soviet Union followed human rights agreements. Later, he became a Physics Professor at Cornell University in the United States.

Contents

Yuri Orlov's Early Life and Career

Yuri Orlov was born on August 13, 1924, in a working-class family near Moscow. His parents were Klavdiya Petrovna Lebedeva and Fyodor Pavlovich Orlov. His father passed away in March 1933.

From 1944 to 1946, Orlov served as an officer in the Soviet army. In 1952, he finished his studies at Moscow State University. He then continued his education and worked as a physicist at the Institute for Theoretical and Experimental Physics.

Speaking Out in 1956

In 1956, Orlov almost lost his science career. He gave a speech at a meeting about a report by Khrushchev. This report talked about the problems caused by Stalin's rule. Orlov bravely called Stalin and another leader, Beria, "killers who were in power." He also demanded "democracy on the basis of socialism," meaning more freedom for people.

Because of this speech, he was removed from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He also lost his job.

Becoming an Expert Physicist

Despite these challenges, Orlov continued his studies. He earned advanced degrees in 1958 and 1963. He became an expert in how particles speed up, which is called particle acceleration. In 1968, he was chosen as a member of the Armenian Academy of Sciences. This happened after he started working at the Yerevan Physics Institute. In 1972, he moved back to Moscow and worked at the Institute of Terrestrial Magnetism.

Standing Up for Human Rights

In September 1973, a newspaper called Pravda published a statement. It was from a group of important scientists who criticized Andrei Sakharov. Sakharov was another famous scientist and human rights activist. Orlov decided to support Sakharov. He remembered how in the 1930s, some scientists demanded punishment for others. Later, those same scientists were arrested themselves.

Open Letters and Activism

To defend Sakharov, Orlov wrote an "Open Letter to L.I. Brezhnev." Brezhnev was the leader of the Soviet Union at the time. The letter explained why the Soviet Union was falling behind in ideas and suggested ways to improve. This letter was secretly passed around in the Soviet Union, a practice called samizdat. Western newspapers published it in 1974, but it wasn't published in Russia until 1991. Orlov also wrote an article asking if a non-totalitarian type of socialism was possible.

In 1973, he was fired from his job again. This was because he helped start the first Amnesty International group in the Soviet Union. Amnesty International is a global organization that works to protect human rights.

Founding the Moscow Helsinki Group

In May 1976, Yuri Orlov created the Moscow Helsinki Group and became its leader. This group's goal was to check if the Soviet Union was following the Helsinki Accords. These were international agreements about human rights. Andrei Sakharov praised Orlov for carefully recording how the Soviet Union broke these human rights rules.

The KGB, the Soviet secret police, told Orlov to close down the Moscow Helsinki Group. They said it was against the law. But Orlov ignored their orders. The head of the KGB, Yuri Andropov, decided that Orlov and other human rights monitors needed to be stopped.

Arrest and Unfair Trial

On February 10, 1977, Yuri Orlov was arrested. In March 1977, he wrote an article from prison called "The road to my arrest." His trial was held in secret, and he was not allowed to see the evidence against him or call witnesses to speak for him.

The courtroom was filled with people chosen by the authorities. Orlov's friends and supporters, including Andrei Sakharov, were not allowed inside. The judge and prosecutor often interrupted Orlov when he was speaking. Some people in the courtroom even shouted "spy" and "traitor." Orlov's wife, Irina, said that the hostile crowd cheered his sentence and shouted for him to get an even harsher punishment.

At his trial, Orlov argued that he had the right to criticize the government. He also said he had the right to share information, based on the freedom of information rules in the Helsinki Accords. He explained that he shared this information to help people, not to cause trouble. On May 15, 1978, Orlov was sentenced to seven years in a labor camp and five years of internal exile. This was all because of his work with the Moscow Helsinki Group.

Protests Against Orlov's Trial

Many people around the world were upset about Orlov's unfair trial. US President Jimmy Carter said he was worried about how harsh the sentence was and how secret the trial had been. Senator Henry M. Jackson from Washington said that Orlov's trial showed how the Soviet Union was breaking its own laws. The US National Academy of Sciences officially protested against the trial.

In 1978, 2,400 American scientists, including physicists, formed a group called Scientists for Sakharov, Orlov and Shcharansky (SOS). This group worked to protect the human rights of scientists around the world. Scientists at CERN also spoke out against Orlov's imprisonment. Many physicists canceled their trips to the Soviet Union to protest his jailing.

Imprisonment and Exile

Yuri Orlov spent a year and a half in Lefortovo Prison. Then he was moved to labor camps in Perm. In one camp, Perm Camp 37, he went on three hunger strikes. He did this to get the prison authorities to return his writings and notes that they had taken. Two articles he wrote in the camp were secretly sent out and published in other countries. In 1983, the Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky asked the Soviet leader Yuri Andropov to release Orlov, but there was no answer.

The Helsinki Watch group, based in New York, reported that Orlov's health was getting worse. He had frequent headaches and dizzy spells from an old head injury. He also suffered from kidney and prostate problems, low blood pressure, and other pains. Medical care in the labor camp was very poor. Orlov also suffered from tuberculosis. He lost a lot of weight and most of his teeth. His wife said he looked very thin and that she was "very fearful for my husband's health. The authorities are gradually killing him."

In 1984, Orlov was sent to Kobyay in Siberia, a very cold and remote place. He was allowed to buy a house with a garden there. In 1985, Professor George Wald spoke to the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev about Orlov's case. Gorbachev said he had not heard of Orlov.

Freedom and New Life in the US

On September 30, 1986, the KGB decided to send Orlov out of the Soviet Union. They also took away his Soviet citizenship. This was part of a deal between the US and the Soviet Union to release an American journalist. Orlov's release gave hope that human rights might improve in the Soviet Union. US President Jimmy Carter was very happy about Orlov's release.

On December 10, 1986, Orlov received the Carter–Menil Human Rights Prize, which came with $100,000. In 1987, Orlov started working at Cornell University as a scientist and professor. He also visited the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in 1988 and 1989. Orlov became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He continued to study particle accelerator design and quantum mechanics. He wrote many research papers, articles about human rights, and an autobiography called Dangerous Thoughts (1991).

In 1990, Gorbachev gave Soviet citizenship back to Orlov and 23 other important exiles. Orlov told Gorbachev that he had great power and should use it to make reforms without fear. He also said Gorbachev should get rid of the KGB, calling it a "cancer." In 1991, Orlov and Elena Bonner wrote an open letter about the Soviet army deporting Armenians from Azerbaijan to Armenia.

In 1993, Orlov became an American citizen.

Awards and Later Views

In 1995, the American Physical Society gave him the Nicholson Medal for Humanitarian Service. In 2005, he was the first person to receive the Andrei Sakharov Prize. This award honors scientists who do great work in promoting human rights. In 2020, just before he passed away, the American Physical Society gave him the 2021 Robert R. Wilson Prize. This was for his scientific work and for "embodying the spirit of scientific freedom."

In 2004, Orlov shared his thoughts about Russia and its leader, Vladimir Putin. He said, "Russia is flying backwards in time. Putin is like Stalin, and he speaks in the language of the thug, the mafia." In 2005, Orlov wrote a letter to Putin. He expressed concern about the legal action against people involved in an art exhibition about religion at the Sakharov Museum.

Orlov appeared in two documentaries about the Soviet dissident movement: They Chose Freedom in 2005 and Parallels, Events, People in 2014. He was also a member of committees for Human Rights Watch and Global Rights.

Yuri Orlov passed away on September 27, 2020, at the age of 96.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Yuri Orlov para niños

In Spanish: Yuri Orlov para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |