Álvaro d'Ors Pérez-Peix facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Álvaro d'Ors Pérez-Peix

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Álvaro d'Ors Pérez-Peix

14 April 1915 Barcelona, Spain

|

| Died | 1 February 2004 (aged 88) Pamplona, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | academic |

| Known for | scholar of law, political theorist |

| Political party | Carlism |

Álvaro Jordi d'Ors Rovira y Pérez-Peix (born April 14, 1915 – died February 1, 2004) was a Spanish expert in Roman law. He is known as one of the most important Roman law scholars of the 20th century. He worked as a professor at the University of Santiago de Compostela and the University of Navarra. He was also a legal thinker and political theorist. He helped develop a Traditionalist view of how the government and society should work. In politics, he supported the Carlist movement. Even though he didn't hold official positions, he was a leading thinker for the Carlists and advised their leader.

Contents

Family and Early Life

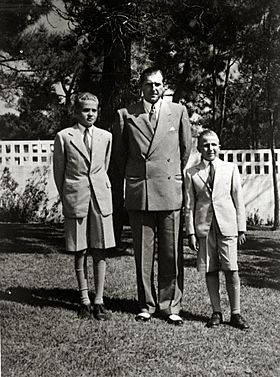

Álvaro d'Ors's family, the Ors, had lived in Catalonia, Spain, for many centuries. His great-grandfather was from Sabadell, and his grandfather, José Ors Rosal, became a doctor in Barcelona. Álvaro's father, Eugenio d'Ors (1881-1954), was a very important cultural figure in Catalonia in the 1910s. He later became famous across Spain as a writer, art critic, and philosopher. He held high positions related to culture during the Francoist era.

In 1906, Eugenio married María Pérez Peix, who came from a wealthy family in Barcelona. She was a talented person who enjoyed music, dance, and especially sculpture. Álvaro was the youngest of their three sons. He grew up in a rich and artistic home. His family traveled a lot because of his father's work. In 1922, they moved to Madrid.

Álvaro first learned from his mother. From 1923 to 1932, he attended Instituto-Escuela, a school known for its liberal ideas. He finished his high school studies there. In 1932, he started studying law, and in 1933, he began studying philosophy and literature.

When the Spanish Civil War started, Álvaro was at his family's home in Argentona. Because his father supported the Nationalist side, Álvaro stayed hidden for a while. In 1937, he went through France to reach the Nationalist zone. He was drafted into the army but then joined the Carlist volunteer troops, called requeté units. He served with them until 1939. That same year, he finished his law degree and started teaching at Universidad Central.

In 1945, d'Ors married Palmira Lois Estévez (1920-2003), who was one of his students. They had 11 children. Three of his sons became academics: Miguel (literature), Javier (law), and Angel (philosophy). His daughters became editors, historians, or art critics. His nephew, Pablo d'Ors Führer, is a well-known Catholic priest and writer.

Academic Career

Álvaro d'Ors began his teaching career in 1939, working as an assistant in Roman law in Madrid. In 1940, he went to Italy to do research for his PhD dissertation. He wrote his thesis on the Constitutio Antoniniana, a Roman law, and earned his PhD in 1941.

In 1943, he became a professor of Roman law at the University of Granada. In 1944, he moved to the Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, where he had already been working since the early 1940s. Besides Roman law, he also taught Civil Law and History of Law. In the late 1940s, he was the Library Director at the University of Santiago.

From 1953 to 1973, d'Ors led the Istituto Giuridico Spagnolo, an institute based in the Vatican. In 1960, he moved to the new University of Navarra in Pamplona, which was connected to Opus Dei. He continued as a Roman law professor there for 24 years. He also served as Library Director and helped set up the School of Librarians. He retired in Pamplona in 1985 but continued to teach as a professor emeritus until 1989 and as an honorary professor until his death.

D'Ors was also active in many research centers and was on the editorial boards of several academic journals. He wrote a lot throughout his life, publishing hundreds of academic works and many articles for newspapers.

People had different opinions about his teaching style. Many said he was very fair and respectful to his students and assistants, giving them a lot of freedom in their research. Some even said he was too kind. His son said he didn't have personal enemies. However, others believed he was only lenient with his own students and strict with those who disagreed with him, saying his views were sometimes affected by his strong beliefs.

Roman Law Expert

Even though d'Ors worked in many academic areas, he saw himself, and is best known today, as an expert in Roman law. His interest in ancient Rome began when he visited the British Museum as a child. He learned a lot from his teachers, José Castillejo and Ursicino Alvarez. He also admired famous scholars like Theodor Mommsen and Max Kaser.

He studied many specific topics in Roman law. One of his first interests was Roman citizenship rules. He offered a new way to understand the Edict of Caracalla, which granted Roman citizenship to almost all free people in the Roman Empire. He also studied agreements and contracts, especially those related to credit.

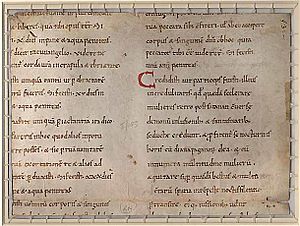

D'Ors spent a lot of time researching municipal law, which is the law of cities, especially during the Flavian era. He also worked on putting back together the Praetor's Edict, which was a set of rules announced by Roman officials. He improved earlier attempts to reconstruct it. He also studied Visigothic law, which was the law of the Visigoths, a Germanic people who ruled parts of Spain. He argued that their law applied to the land, not just to specific people. Finally, he deeply analyzed the legal ideas of the Roman jurist Sextus Caecilius Africanus.

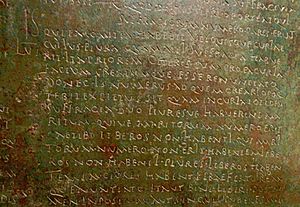

When it came to his methods, d'Ors believed in being very strict and careful when studying Roman legal sources. He focused on sources that hadn't been fully appreciated before, like papyrology (the study of ancient writings on papyrus) and epigraphy (the study of inscriptions). In the 1950s, he collected and explained all known inscriptions related to Roman law in Roman Spain. He later followed new discoveries, especially the Lex Flavia and Lex Irnitana in the 1980s.

Some of his most important books include Estudios sobre la Constitutio Antoniniana (1943), which was his PhD work. Epigrafía jurídica de la España romana (1953) is considered by some to be his most important contribution to Roman law studies. In 1960, he published El Código de Eurico, a major work on Visigothic law. His book Elementos de Derecho romano (1960) was a textbook for students and was reprinted many times, helping generations of Spanish law students. His last major work was a collection of essays called Crítica romanística (1999). He also wrote hundreds of shorter articles.

Legal and Political Ideas

D'Ors had a special way of thinking about law. He believed there was a difference between authority (autoridad) and power (poder). Authority comes from true wisdom, which he thought came from tradition and natural order, based on divine rules. Power, on the other hand, is the ruling structure. He believed power should be based on authority but should also be separate from it. He thought this ideal worked best in the early Roman Republic. He felt that when this difference was lost, especially after the rise of Protestantism, it led to less freedom because rulers took on both roles.

Another idea he had was the difference between legitimacy (legitimidad), which comes from natural law, and legality (legalidad), which comes from rules made by those in power. He believed these two should work together. But he felt that natural law was being challenged by positive law (laws made by humans). He didn't like the idea that laws were just based on agreements or the "will of the people," calling these ideas a "myth."

D'Ors also thought about violence. He saw it as a part of human history, often appearing when an old order was breaking down. He considered himself a "realist" and believed that in extreme situations, violence might be necessary to protect the natural order from chaos. He even thought that if violence came from a true authority, it could be part of what is right, even if it wasn't strictly legal.

His ideas about law and politics are sometimes hard to tell apart. He didn't write one big book explaining all his theories. Instead, his ideas are found in many articles, letters, and essays. Some of his important collections of essays include Escritos varios sobre el Derecho en crisis (1973) and Derecho y Sentido Común (1995).

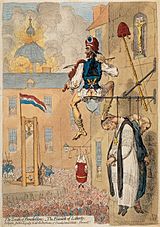

A main part of d'Ors's political ideas was his criticism of the modern state. He thought modern states were created after the 16th century and religious wars, becoming stronger with absolute monarchies and the French Revolution. He believed these states mixed up authority and power, creating "artificial" nation-states. He suggested that a better way for countries to organize themselves in the late 20th century would be through "great spaces," which some people compare to large confederations or groups like the British commonwealth. He also tried to create a new field of study called "geodieretics," which focused on organizing land based on the idea of subsidiarity (where decisions are made at the lowest possible level).

D'Ors had a "counter-revolutionary" idea for how human groups should be organized. Instead of equality, he focused on legitimacy, based on family, natural law, and divine truth. Instead of liberty, he emphasized responsibility, based on personal identity and service. Instead of brotherhood, he promoted fatherhood, based on authority, wisdom, and public good. His ideas included valuing tradition, strong leadership, Christianity, monarchy, and authority, while being less focused on reason, democracy, and nationalism.

Some historians call d'Ors a supporter of Franco's regime. They point out that his ideas about violence and his support for a "Crusade" fit well with the regime. However, other scholars say that d'Ors supported Francoism only when it upheld traditional values and that he opposed parts of the regime that were too revolutionary. He also became critical of Spain joining the European economic community, seeing it as falling prey to global capitalism.

He didn't write one main book on his political theory. His ideas are found in many essays and collections like De la guerra y la paz (1954) and Ensayos de Teoría Política (1979).

Local Laws and Church Law

Throughout his career, d'Ors was interested in specific local laws called fueros, which were unique to certain towns, provinces, and regions in Spain. In 1946, he spoke at a conference where he supported these local rights. This was a way of speaking against the central government's efforts to make all laws the same.

He continued to develop his idea of subsidiarity, which meant that local communities should have more say in their own laws. In the 1960s, he joined a team working to write down the regional laws of Navarre. This work resulted in the Fuero Nuevo de Navarra (1968-1971). D'Ors believed these Navarrese laws came from a true authority and were based on natural law. After Franco's rule ended, d'Ors helped work on a new law for Navarre, but his ideas were not fully accepted by the local government. He then focused on smaller areas, helping to complete the Ordenanzas del Valle de Salazar, which were specific laws for a community in the Pyrenees.

D'Ors was also interested in canon law, which is the law of the Catholic Church. From 1961 to 1985, he taught canon law at the University of Navarra. When a new Code of Canon Law was released in 1983, he focused on the legal terms used and the Latin versions of the rules. He helped revise the Spanish translation of the Code of Canon Law, published in 2001.

Another broad academic interest of d'Ors was how to classify different sciences. He developed a system in the 1960s that divided sciences into Human Sciences, Natural Sciences, and Geonomic Sciences (which dealt with organizing the land). Law was part of the Human Sciences. His ideas on this were put into a large work called Sistema de las Ciencias (1969).

Carlist Involvement

While there were some distant Carlist connections in his family, Álvaro's parents were part of a modern, artistic group. In his youth, d'Ors followed a more liberal path. He co-founded an art magazine in the late 1920s that was considered "progressive." During his university years, he wasn't very involved in politics.

When the Civil War started, he spent the first year reading. He went to the Nationalist zone because of his father's views. However, he was drawn to the volunteer Carlist troops, known as the requeté. He joined the Tercio Burgos-Sangüesa battalion and later the Tercio de Navarra. His time in these units shaped him into a Carlist.

After leaving the army in 1939, d'Ors didn't immediately get involved in politics. When he started teaching in Santiago in the mid-1940s, he reconnected with local Carlist groups, but he didn't hold any official positions within the movement. Carlism was often divided, and d'Ors didn't openly support any specific group. He mostly focused on developing his Traditionalist ideas through his legal and political theories.

His connection with the Carlist movement became stronger in the late 1950s. The young people around Prince Carlos Hugo, who was just starting to become a public figure, asked d'Ors for help. D'Ors helped write a speech for the prince to give at the annual Carlist Montejurra rally in 1958. This speech talked about local laws, subsidiarity, and a united Europe. In 1960, he gave a lecture on his political ideas at a Traditionalist conference.

Around 1960, d'Ors was not widely known as a strong Carlist supporter. Some politicians from the Alfonsist side (who supported a different royal line) even thought he might be an ally. When Franco decided to set up an academic board to guide the education of Don Juan Carlos (who later became king), Don Juan's supporters suggested d'Ors as a member. However, d'Ors refused, stating that his loyalty was to the Carlist dynasty and its leader, Don Javier.

Peak of Carlist Involvement

The early 1960s marked the start of d'Ors's more open involvement in Carlist activities. In 1962, he helped create a document that supported the citizenship claims of the Borbón-Parmas family, which was presented to Franco. D'Ors went with Don Carlos Hugo to this meeting but was not allowed to join the interview. He later said that until then, he had believed Franco might crown a Carlist leader. This meeting convinced him it was an illusion, but he continued to support the Borbón-Parmas out of loyalty.

In 1964, d'Ors prepared documents for a major Carlist meeting in Puchheim, which he attended the following year. As a legal expert, he worked on the case of Don Sixto, who was facing expulsion from Spain. In 1965, he spoke at the Montejurra rally for the only time, discussing the legitimacy of the Borbón-Parmas, which had a big impact.

In 1965, d'Ors was appointed to the Junta del Gobierno, a Carlist governing body. In 1966, he joined the new Consejo Asesor de la Jefatura Delegada and was mentioned in the press as a member of the Junta Nacional. In 1968, he joined another important group, the Consejo Real. He continued to be the chief legal advisor to Don Javier, helping to draft important declarations.

From the early 1960s, Carlism became more divided between a progressive group led by Don Carlos Hugo and the traditionalist core. By the mid-1960s, the progressives controlled the main Carlist organizations. There is little information about d'Ors's involvement in these internal struggles. Although he was a key traditionalist thinker and spoke against revolutionary ideas, he was often published in the progressive Carlist magazine Montejurra until 1968.

However, in the late 1960s, he became increasingly unhappy with the new ideas introduced by Don Carlos Hugo and his group. He told Don Carlos Hugo, "Your Highness is a republican," and began to distance himself from the party. In the early 1970s, after large rallies by Carlos Hugo's supporters, d'Ors left the Consejo del Rey and ended his ties with the new Partido Carlista.

Carlism After Franco

From the early 1970s, d'Ors stayed away from the official Carlist groups controlled by Carlos Hugo's followers. He was also very disappointed by Don Javier, who seemed to approve of his son's socialist-leaning efforts. However, d'Ors did not openly fight them.

In 1976, encouraged by his daughter, he attended the annual Montejurra rally. He later said he didn't know that traditionalists planned to confront Don Carlos Hugo and his supporters at the event. When the gathering turned into a fight (known as the Montejurra massacre), he left. However, some newspapers later claimed d'Ors encouraged the traditionalist fighters. Afterward, he visited some of them in prison.

Little is known about d'Ors's Carlist activities around 1980. In the early 1980s, he kept in touch with traditionalist activists and thinkers. He sometimes attended conferences or public rallies. As many small Carlist groups tried to unite, d'Ors was very supportive. He was present at a unification rally in 1986, which led to the creation of the Comunión Tradicionalista Carlista (CTC). He was elected to its executive council, the Consejo Nacional. However, he was more of a respected elder than an active politician.

One exception was the European Parliament elections in 1994. He agreed to be the last candidate on the CTC list to lend his prestige to other Carlist candidates. However, they did not win.

As an octogenarian (in his 80s), d'Ors believed Carlism was no longer a strong political force. In a letter from 2000, he wrote that the role of the CTC was "to save the principles of Tradition against the democratic correctness that rules today." It's not clear what he thought about another split in the movement when followers of Don Sixto formed their own group. Some sources say d'Ors remained on the CTC executive until his death.

In 2002, d'Ors faced strong criticism from the Sixtinos (Don Sixto's followers). This happened after he wrote an article suggesting that the Carlist motto "Dios Patria Rey" (God, Homeland, King) was somewhat outdated. D'Ors suggested that religious questions were now mostly private, patriotism meant defending local laws, and a king was more a symbol of monarchy than a specific person or family. The Sixtino leader, Rafael Gambra, strongly disagreed, accusing d'Ors of trying to turn Carlism into just "one more Christian-democratic group."

See Also

In Spanish: Álvaro d'Ors para niños

In Spanish: Álvaro d'Ors para niños

Images for kids