André Glucksmann facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

André Glucksmann

|

|

|---|---|

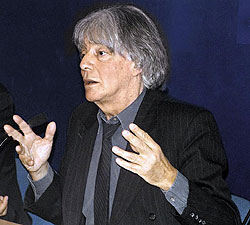

André Glucksmann in January 2012

|

|

| Born | 19 June 1937 Boulogne-Billancourt, France

|

| Died | 10 November 2015 (aged 78) Paris, France

|

| Alma mater | École normale supérieure de Saint-Cloud |

| Era | 20th-/21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Nouveaux Philosophes |

|

Main interests

|

Political philosophy |

André Glucksmann (French: [ɡlyksman]; born June 19, 1937 – died November 10, 2015) was an important French thinker, activist, and writer. He was a main figure in a group called the New Philosophers.

Glucksmann started his career following the ideas of Marxism. However, he later changed his mind and rejected communism. He wrote a popular book called La Cuisinière et le Mangeur d'Hommes (1975) about this. He became a strong critic of the Soviet Union and later, Russia's foreign policy. He was also a big supporter of human rights. In his later years, he disagreed with the idea that Islamic terrorism was caused by a "clash of civilizations" between Islam and the West.

Contents

André Glucksmann's Early Life

André Glucksmann was born in 1937 in Boulogne-Billancourt, France. His parents were Ashkenazi Jews from Austria-Hungary. His father was from a region that is now part of Romania, and his mother was from Prague, which is now the capital of Czechoslovakia.

Glucksmann's father died during World War II. His mother and sister were active in the French Resistance, a group that fought against the occupation of France. His family barely escaped being sent to concentration camps during the Holocaust. This terrible event deeply shaped Glucksmann's ideas. It made him think of the "state" (meaning the government or country) as a possible source of great cruelty.

He went to school at the Lycée la Martinière in Lyon. Later, he studied at the École normale supérieure de Saint-Cloud. His first book, Le Discours de la Guerre (The Discourse of War), was published in 1968.

André Glucksmann's Career and Ideas

Becoming a "New Philosopher"

In 1975, Glucksmann published his book La Cuisinière et le Mangeur d'Hommes (The Cook and the Man-Eater). The subtitle was Reflections on the State, Marxism, and Concentration Camps. In this book, he argued that Marxism could lead to totalitarianism. He showed similarities between the terrible acts of Nazism and Communism.

His next book, Les maîtres penseurs (The Master Thinkers), came out in 1977. In it, he looked at how ideas from German philosophers like Fichte, Hegel, Marx, and Nietzsche might have led to totalitarian thinking.

During the Vietnam War, Glucksmann became well-known for supporting the Vietnamese boat people. These were people who fled Vietnam by boat after the war. He started working with another philosopher, Bernard-Henri Lévy, to criticize Communism. Both of them had once been Marxists. Soon after, they and others who rejected Marxism became known as the New Philosophers. Lévy actually created this term.

Political Views in the 80s and 90s

In 1985, Glucksmann signed a letter to President Reagan. The letter asked Reagan to keep supporting the Contras in Nicaragua. After the Berlin Wall fell, Glucksmann became a supporter of using nuclear power. In 1995, he supported Jacques Chirac's decision to restart nuclear tests. He also supported NATO's military action in Serbia in 1999. He also called for Chechnya to become an independent country.

Glucksmann's Philosophy on Terrorism

In his book Dostoyevsky in Manhattan, Glucksmann wrote about nihilism. Nihilism is the belief that life has no meaning or purpose. He said that nihilism, especially as shown by Dostoyevsky in his novels Demons and The Brothers Karamazov, is a key part of modern terrorism.

Later Years and Global Politics

Glucksmann supported military actions by Western countries in Afghanistan and Iraq. He was very critical of Russia's foreign policy. For example, he supported independence for the Chechen people. However, he was against Abkhazia and South Ossetia becoming independent from Georgia. He argued that Georgia was important for Europe to get oil and gas without relying too much on Russia. He believed that if Tbilisi (Georgia's capital) fell, it would be harder to get energy from Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan.

As an example of Russia possibly using energy as a weapon, Glucksmann mentioned a funny, critical song about Gazprom (a Russian energy company). The song joked about blocking gas if Russia didn't win the Eurovision Song Contest. Glucksmann used this as "proof" that the Russian people wanted to cut off gas to Ukraine and Europe.

Glucksmann supported Nicolas Sarkozy in the 2007 French presidential election. In August 2008, he signed an open letter with famous people like Václav Havel and Desmond Tutu. The letter asked Chinese authorities to respect human rights during and after the Beijing Olympic Games. He also signed the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism.

André Glucksmann's Death

André Glucksmann passed away in Paris on November 10, 2015, at the age of 78.

After his death, French President François Hollande said that Glucksmann always "listened to the suffering of peoples." Former president Nicolas Sarkozy said that Glucksmann "turned a page in French thought from the second half of the 20th Century."

Books by André Glucksmann

- Voltaire counter-attacks (Voltaire Contre-Attaque) (2014)

- A Child's Rage (Une rage d'enfant) (2006)

- The Discourse of Hate (Le Discours de la haine) (2004)

- West Versus West (Ouest contre Ouest) (2003)

- Dostoyevsky in Manhattan (Dostoïevski à Manhattan) (2002)

- The Third Death of God (La Troisième Mort de Dieu) (2000)

- Silence, Killing in Process (Silence, on tue) (1986) (with Thierry Wolton)

- Stupidity (La Bêtise) (1985)

- Cynicism and Passion (Cynisme et passion) (1981/1999)

- The Force of Vertigo (La Force du vertige) (1983)

- The Master Thinkers (Les Maîtres penseurs) (1977)

Note: Many of his books were translated into German by his long-time colleague Helmut Kohlenberger.

Interviews

- "An Interview with Andre Glucksman". Telos 33 (Fall 1977). New York: Telos Press

See also

In Spanish: André Glucksmann para niños

In Spanish: André Glucksmann para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |