Andranik facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Andranik

|

|

|---|---|

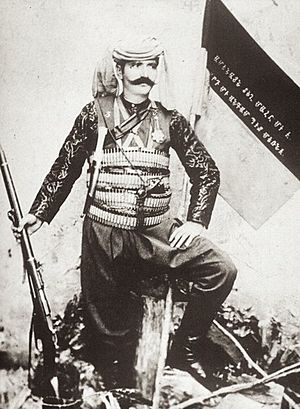

General Andranik Ozanian, wearing his uniform and medals with a papakha hat

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Andranik pasha |

| Born | 25 February 1865 Shabin-Karahisar, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 31 August 1927 (aged 62) Richardson Springs, California, U.S. |

| Buried |

Ararat Cemetery (1927–28)

Père Lachaise (1928–2000) Yerablur (2000–present) |

| Allegiance | Armenian paramilitaries (1917–19) |

| Years of service | 1888–1904 (fedayi) 1912–13 (Bulgaria) 1914–16 (WWI) 1917–19 (Armenia) |

| Rank | Commander of the fedayi (1899–1904) Commander of the Western Armenian division of the Armenian Army Corps (1918) Commander of the Special Striking Division (1919) |

| Wars | Armenian National Liberation Movement Sasun Uprising First Balkan War World War I

|

| Awards | see below |

| Signature | |

Andranik Ozanian (born February 25, 1865 – died August 31, 1927), often known as General Andranik, was an important Armenian military leader and statesman. He was a key figure in the Armenian national liberation movement. From the late 1800s to the early 1900s, he was one of the main Armenian leaders fighting for Armenia's independence.

Andranik started fighting against the Ottoman government in the late 1880s. He joined the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktustyun) party. With other Armenian fedayi (which means "freedom fighters"), he worked to protect Armenian villagers in their homeland, known as Western Armenia. This area was part of the Ottoman Empire at the time.

His revolutionary actions stopped after an uprising in Sasun in 1904 was not successful. In 1907, Andranik left the Dashnaktustyun party. He did not agree with their decision to work with the Young Turks, a group that later caused the Armenian Genocide. Between 1912 and 1913, Andranik led Armenian volunteers within the Bulgarian army against the Ottomans during the First Balkan War.

During World War I, Andranik commanded the first Armenian volunteer battalion for the Russian army against the Ottoman Empire. He helped capture and govern parts of the traditional Armenian homeland. After the Revolution of 1917, the Russian army left, and Armenian fighters were outnumbered by the Turks. Andranik led the defense of Erzurum in early 1918 but had to retreat. By May 1918, Turkish forces were close to Yerevan, the future capital of Armenia. They were stopped at the Battle of Sardarabad.

The Armenian National Council declared Armenia's independence and signed the Treaty of Batum with the Ottoman Empire. This treaty meant Armenia gave up its rights to Western Armenia. Andranik never accepted this new First Republic of Armenia because it was too small. He continued to fight in Zangezur against Azerbaijani and Turkish armies, helping to keep that region as part of Armenia.

Andranik left Armenia in 1919 due to disagreements with the Armenian government. He spent his last years in Europe and the United States, helping Armenian refugees. He settled in Fresno, California in 1922 and died five years later. Andranik is deeply admired as a national hero by Armenians. Many statues, streets, and songs honor him, making him a legendary figure in Armenian culture.

Contents

Early Life and Becoming a Freedom Fighter

Andranik Ozanian was born on February 25, 1865, in Shabin-Karahisar, a town in the Ottoman Empire. His name, Andranik, means "firstborn" in Armenian. His family had moved to Shabin-Karahisar to escape persecution. Andranik's mother died when he was very young, and his older sister took care of him. He went to school until he was 17, then worked in his father's carpentry shop. He married at 17, but his wife and their baby died a year later.

Life for Armenians in the Ottoman Empire became harder under Sultan Abdul Hamid II. In 1882, Andranik was arrested for fighting a Turkish police officer who was mistreating Armenians. He escaped from prison with help from friends. He lived in Constantinople for a few years, working as a carpenter.

Andranik started his revolutionary activities in 1888. He joined the Hunchak party in 1891. In 1892, he was arrested again for being involved in the killing of Constantinople's police chief, who was known for being against Armenians. Andranik escaped from prison once more. Later in 1892, he joined the new Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF or Dashnaktsutyun).

Standing Up for Armenians

During the Hamidian massacres, which were terrible mass killings between 1894 and 1896, Andranik and other fedayi defended Armenian villages in Mush and Sasun. They protected them from attacks by Turkish soldiers and Kurdish groups. These massacres, named after Sultan Abdul Hamid II, resulted in the deaths of many thousands of Armenians.

In 1897, Andranik went to Tiflis, a major Armenian cultural center in the Caucasus. From there, he returned to Turkish Armenia with weapons for the fedayi. Many Russian Armenians joined him. They went to the Mush-Sasun area, where another leader, Aghbiur Serob, had already created semi-independent Armenian areas.

Leader of the Fedayi

Aghbiur Serob, a main leader of the fedayi, was killed in 1899 by a Kurdish leader named Bushare Khalil Bey. This Bey later killed more Armenians. Andranik took Serob's place as the head of the Armenian fighters in the Mush-Sasun region. This area had many Armenians who were ready to fight for their freedom. Andranik sought revenge for Serob's death and reportedly killed Bey. This made Andranik a respected leader among his fedayi.

Even though small groups of Armenian fedayi fought against the Ottoman government, the situation for Armenians in Western Armenia got worse. European countries did not help much with the "Armenian Question," which was about the rights and safety of Armenians. The Treaty of Berlin from 1878 had promised reforms and safety for Armenians, but these promises were not kept.

Battle of Holy Apostles Monastery

In November 1901, Andranik and his fedayi fought Ottoman troops in what became known as the Battle of Holy Apostles Monastery. This was a major event where the Ottoman government tried to stop Andranik. More than 5,000 Turkish soldiers were sent to capture him and his group of about 50 men. They surrounded Andranik and his men at the Arakelots (Holy Apostles) Monastery.

After weeks of fighting and talks, Andranik and his men managed to escape. It is said that Andranik, dressed as a Turkish officer, walked past the guards and helped his men get out. After breaking through the siege, Andranik became a legend among Armenians. He wanted to show the world the difficult situation of Armenian peasants and give hope to his people.

The Sasun Uprising

In 1903, Andranik demanded that the Ottoman government stop bothering Armenians and make reforms in Armenian areas. Most fedayi were in the mountainous region of Sasun, where most people were Armenian. This area had been in "revolutionary turmoil" because Armenians there had refused to pay taxes for seven years.

Andranik and other fedayi leaders met in 1903 to plan how to defend Armenian villages from Turkish and Kurdish attacks. They decided on a local uprising in Sasun, as they did not have enough resources for a bigger fight. Andranik was chosen as the main commander.

The fighting began in January 1904. The Turkish army, with 10,000 to 20,000 soldiers and 7,000 Kurdish fighters, attacked. The Armenians had only 100 to 200 fedayi and about 700 to 1,000 local men. Many Armenian civilians were killed during the two-month uprising, and thousands lost their homes.

By May 1904, the Ottoman forces had crushed the uprising because they greatly outnumbered the Armenians. Andranik and his fedayi escaped to Lake Van and then to Persia in September 1904. They left behind a heroic memory. Some say they left to avoid more killings and reduce tensions. Others say Andranik wanted to find new ways to help the Armenian struggle.

Joining the Balkan War

From Persia, Andranik went to the Caucasus, where he met Armenian leaders. Then he traveled to Europe, speaking out for the Armenian national liberation movement. In 1906, he published a book in Geneva about military tactics, sharing his experiences from the Sasun uprising.

In 1907, Andranik attended a meeting of the ARF party in Vienna. The ARF decided to work with the Young Turks to overthrow the Sultan. Andranik strongly disagreed with this cooperation and left the party. He knew that the Young Turks would later commit terrible acts against Armenians. For several years, Andranik stayed away from active politics and military affairs.

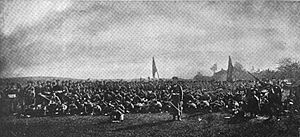

In 1907, Andranik settled in Sofia, Bulgaria. There, he met leaders of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. They agreed to work together for the freedom of Armenians and Macedonians. During the First Balkan War (1912–13), Andranik led a group of 230 Armenian volunteers. They fought alongside the Bulgarian army against the Ottoman Empire. Andranik was given the rank of first lieutenant by the Bulgarian government. He showed great bravery in battles and was honored with the Order of Bravery. He disbanded his men in May 1913 and lived as a farmer until August 1914.

World War I and Protecting Armenians

When World War I began in July 1914, Andranik left Bulgaria for Russia. The Russian government made him the commander of the first Armenian volunteer battalion. From November 1914 to August 1915, Andranik fought in the Caucasus Campaign with about 1,200 volunteers in the Imperial Russian Army. His battalion was especially brave at the Battle of Dilman in April 1915. This victory helped stop the Turks from invading the Caucasus.

Fighting in Western Armenia

During 1915, the Armenian genocide was happening in the Ottoman Empire. Most Armenians in their homeland were killed or forced to leave. About 1.5 million Armenians died, ending the Armenian presence in Western Armenia. The only major resistance was in Van, where local Armenians fought off the Turkish army until Armenian volunteers arrived. Andranik and his unit entered Van on May 19, 1915. He then helped the Russian army take control of other towns.

By 1916, the Russian army had control of most of the Armenian plateau. The Russian government then ordered the Armenian volunteer units to be disbanded. Andranik was disappointed and resigned as commander. He and other Armenian volunteers left the front in July 1916.

Retreat and New Challenges

The February Revolution in 1917 was welcomed by Armenians because it ended the rule of Nicholas II. A new government was set up in the South Caucasus. In April 1917, Andranik started a newspaper called Hayastan (Armenia) in Tiflis. He also helped Armenian refugees from the Ottoman Empire.

After the October Revolution in 1917, Russian troops began to leave Western Armenia in a chaotic way. Bolshevik Russia and the Ottoman Empire signed a ceasefire in December 1917. Russia then signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, giving up Western Armenia and other areas to focus on its own civil war.

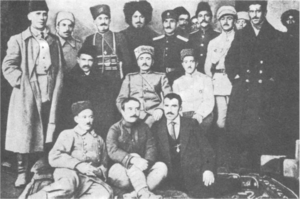

In December 1917, as Russian soldiers left, the Russian command allowed the formation of the Armenian Army Corps. Andranik commanded the Western Armenian division. He was appointed major-general in January 1918. However, Andranik could not defend Erzurum for long, and the Turks captured the city on March 12, 1918.

Turkish forces quickly took back Armenian areas. Andranik retreated through Kars and Alexandropol. By early April 1918, Turkish forces had reached the pre-war borders. Andranik and his unit were not able to take part in the important battles of Sardarabad, Abaran, and Karakilisa.

The First Republic of Armenia and Zangezur

After the Ottoman forces were stopped at Sardarabad, the Armenian National Council declared the independence of Armenian lands on May 28, 1918. Andranik did not agree with this decision and criticized the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. He believed the new Republic of Armenia was too small and controlled by Turkey. He saw the signing of the Treaty of Batum as a betrayal. Many Armenians from Turkish Armenia felt the new republic was not enough.

In early June, Andranik left Dilijan with thousands of refugees. They traveled to Nakhichevan on June 17. He tried to help Armenian refugees from Van in Iran. He wanted to join British forces, but after seeing many Turkish soldiers, he returned to Nakhichevan. On July 14, 1918, he declared Nakhichevan part of (Soviet) Russia. This was supported by Armenian Bolshevik leaders.

Protecting Zangezur

As Turkish forces moved towards Nakhichevan, Andranik and his Armenian Special Striking Division went to the mountains of Zangezur to set up a defense. By mid-1918, relations between Armenians and Azerbaijanis in Zangezur were very bad. Andranik arrived in Zangezur at a crucial time with about 30,000 refugees and 3,000 to 5,000 fighters. He took control of the region by September. Zangezur was important because it connected Turkey and Azerbaijan. Under Andranik, it became one of the last places of Armenian resistance after the Treaty of Batum.

Andranik's fighters stayed in Zangezur, surrounded by Muslim villages that controlled important routes. Some historians say Andranik helped make Zangezur a more Armenian land by dealing with Muslim villages. Others say he did not harm peaceful people. Ottoman general Halil Pasha protested Andranik's actions, but Armenia's Prime Minister said he had no control over Andranik.

A Difficult Decision

The Ottoman Empire was defeated in World War I, and the Armistice of Mudros was signed on October 30, 1918. Ottoman forces left Karabakh in November 1918. By late October, Andranik's forces were between Zangezur and Karabakh. He wanted to make sure local Armenians would support him against the Azerbaijanis. In mid-November 1918, he received letters asking him to wait for talks with the Muslims of the region. This delay proved important.

In late November, Andranik's forces moved towards Shushi, the main city of Karabakh. After fighting local Kurds, his forces broke through to nearby villages. By early December, Andranik was close to Shushi. Then he received a message from British General W. M. Thomson in Baku. Thomson asked him to retreat from Karabakh because the war was over. He said further Armenian military action would hurt the Armenian cause at the peace conference in Paris. Trusting the British, Andranik returned to Zangezur.

Because of Andranik's trust in the British officer, Karabakh, which had a large Armenian majority, remained part of Azerbaijan.

During the winter of 1918–19, Zangezur was cut off by snow. Refugees faced famine and disease. In December 1918, Andranik left Karabakh for Goris. He met British officers who suggested his units stay in Zangezur for the winter. Andranik agreed. They also discussed helping the 15,000 refugees from Nakhichevan.

By late February 1919, Andranik was ready to leave Zangezur. On March 22, 1919, he left Goris and traveled through deep snow to the Ararat plain with his fighters. After a three-week march, they reached the railway station of Davalu. He was met by Armenian officials, but he refused to visit Yerevan. He believed the Dashnak government had betrayed Armenians and caused the loss of his homeland. Zangezur became more vulnerable after Andranik left.

On April 13, 1919, Andranik reached Etchmiadzin, the religious center of Armenians. His 5,000-strong division had shrunk to 1,350 soldiers. Due to his disagreements with the government and British actions, Andranik disbanded his division. He gave his belongings and weapons to the Catholicos George V. On April 27, 1919, he left Etchmiadzin with 15 officers and went to Tiflis. Crowds gathered at every station to see their national hero. He left Armenia for the last time.

Later Years and Legacy

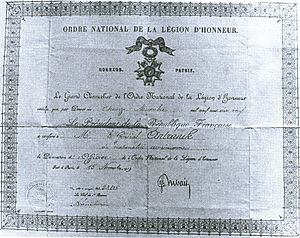

From 1919 to 1922, Andranik traveled across Europe and the United States. He sought support for Armenian refugees. He visited Paris and London, trying to convince Allied powers to help Turkish Armenia. In 1919, he received the Legion of Honor award from the French President. In late 1919, Andranik led a group to the United States to ask for support for Armenia and raise money for the Armenian army. In Fresno, he helped raise $500,000 for Armenian war refugees.

When he returned to Europe, Andranik married Nevarte Kurkjian in Paris on May 15, 1922. They moved to the United States and settled in Fresno, California in 1922. Armenian-American writer William Saroyan described Andranik's arrival, saying it seemed all Armenians in California came to see him. Saroyan described him as a strong man with a white mustache, looking both fierce and kind.

His Final Years

In February 1926, Andranik moved to San Francisco to try and improve his health. He died on August 31, 1927, in Richardson Springs, California, from a heart condition. His funeral in Ararat Cemetery, Fresno, on September 7, 1927, drew public attention. Over 2,500 Armenians attended memorial services in New York on October 9.

He was first buried in Fresno. It was planned to move his remains to Armenia, but Soviet authorities did not allow it. So, his remains were taken to France. After a second funeral in Paris, he was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery on January 29, 1928. In 2000, his body was finally moved to Yerevan, Armenia. It was placed in a complex for two days, then taken to Etchmiadzin Cathedral for a funeral service. Andranik was re-buried at Yerablur military cemetery in Yerevan on February 20, 2000. Armenia's President Robert Kocharyan called him "one of the greatest sons of the Armenian nation." A memorial on his grave reads "General of the Armenians."

A Hero Remembered

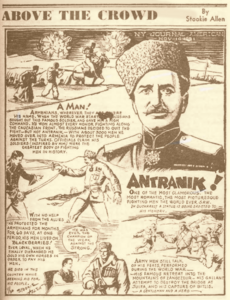

Andranik was seen as a hero during his lifetime. The Literary Digest called him "the Armenian's Robin Hood, Garibaldi, and Washington, all in one." He was praised by famous Armenian writers. He is considered a national hero by Armenians worldwide and a legendary figure in Armenian culture.

During the Soviet era, his legacy was often downplayed because he represented the fight for independence. However, in 1965, Andranik's 100th birthday was celebrated in Soviet Armenia.

Statues and Tributes

Statues and memorials of Andranik have been built around the world. These include places like Bucharest, Paris, Nicosia (Cyprus), Varna (Bulgaria), and Armavir (Russia). There is also a memorial in Richardson Springs, California, where he died. In May 2011, a statue was put up in Volonka, Russia, but it was removed the same day, likely due to pressure from Turkey.

The first statue of Andranik in Armenia was built in 1967 in the village of Ujan. More statues have been built since Armenia became independent in 1991. Three are in Yerevan, the capital. Many streets and squares, both inside and outside Armenia, are named after Andranik. The General Andranik Station of the Yerevan Metro was renamed for him in 1992. In 2006, the Museum of Armenian Fedayi Movement, named after Andranik, reopened in Yerevan.

During the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, Andranik inspired a new generation of Armenians. A volunteer group called "General Andranik" fought in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. Many Armenian groups around the world are named after him. In 2014, Andranik's personal writings, his only known memoir, were returned to Armenia and placed in the History Museum of Armenia.

Andranik in Stories and Songs

Andranik has appeared often in Armenian literature, sometimes as a fictional character. The writer Siamanto wrote a poem about him in 1905. The first book about Andranik was published in 1920. The famous Armenian-American writer William Saroyan wrote a short story called Antranik of Armenia. Another writer, Hamastegh, based his novel The White Horseman on Andranik and other fedayi. Many Armenian poets have written about him.

Andranik's name is remembered in many songs. In 1913, Leon Trotsky called him "a hero of song and legend." He is a main figure in Armenian patriotic songs, sung by artists like Nersik Ispiryan and Harout Pamboukjian. There are dozens of songs dedicated to him, including "Like an Eagle" and "Andranik Pasha." He also appears in the popular song "The Bravehearts of the Caucasus" and other Armenian folk tales.

Several documentaries have been made about Andranik, including "Andranik" (1929) and "General Andranik" (1990).

Awards

Throughout his military career, Andranik received many medals and honors from four different countries. His medals and sword were moved to Armenia and given to the History Museum of Armenia in 2006.

| Country | Award | Rank | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order of Bravery |

"For Bravery" |

1913 | ||

| Order of St. Stanislaus |

with Swords |

1914–16 | ||

| Order of St. Vladimir |

|

1914–16 | ||

| Cross of St. George |

|

1914–16 | ||

| Order of St. George |

|

1914–16 | ||

| Legion of Honor |

|

1919 | ||

| War Cross |

|

1920 |

See also

In Spanish: Andranik Ozanian para niños

In Spanish: Andranik Ozanian para niños

Images for kids