Antonio María Oriol Urquijo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Antonio María de Oriol

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Born |

Antonio María de Oriol y Urquijo

1913 Getxo, Spain

|

| Died | 1996 (aged 82–83) Madrid, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | official, businessman |

| Known for | politician |

| Political party | Carlism, FET, UNE |

Antonio María de Oriol y Urquijo (1913–1996) was an important Spanish politician and businessman. He was a supporter of the Traditionalist movement in Spain. He first joined the Carlist group and later became an official in the Francoist government.

He served in the Spanish parliament, called the Cortes Españolas, from 1955 to 1977. From 1957 to 1965, he led the welfare department in the Ministry of Interior. He then became the Minister of Justice from 1965 to 1973. Later, he was a member of the Council of the Realm (1973–1978) and led the Council of State (1973–1979). As a businessman, he worked for companies owned by his family, like Iberdrola and Patentes Talgo.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Antonio Oriol was born into a family with roots in Catalonia, Spain. His family became known in Spanish history in the 1600s. His great-great-grandfather, Buenaventura Oriol Salvador, supported the legitimists during the First Carlist War. Because of his efforts, he was given the title of Marquesado de Oriol in 1870.

Antonio's paternal grandfather, José María Oriol Gordo (1845–1899), fought in the Third Carlist War. After the war, he settled in Bilbao and married into the wealthy Urigüen family. Antonio's father, José Luis Oriol Urigüen (1877–1972), became a key Carlist politician in Álava in the 1930s. He married Catalina de Urquijo y Vitórica, whose family controlled much of the money in Biscay.

In the early 1900s, Antonio's father, José Luis, took over as CEO of Hidroeléctrica Española. He also started many other businesses and is seen as one of Spain's most important business leaders of the 20th century.

José Luis and Catalina first lived in Getxo, a rich area near Bilbao. They later moved to Madrid. They had 8 children, including Antonio, who was their fourth son. The children grew up in a very wealthy and religious home. Antonio studied law at the Madrid university and finished in 1935. He planned to join the family business after the Spanish Civil War.

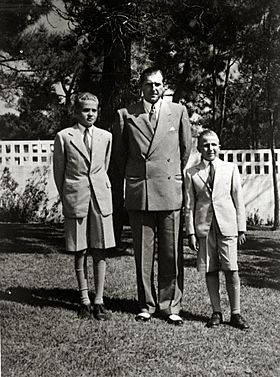

In 1940, Antonio Oriol married María de la Soledad Díaz de Bustamante y Quijano (who passed away in 1990). Her family was also wealthy and from Cantabria. Antonio and Soledad lived at the large Oriol family estate near Majadahonda. Antonio's brothers, Lucas and José María, also lived there and became important officials and business leaders under Franco.

Antonio and Soledad had seven children. All their sons became top business executives. Their daughter María married Miguel Primo de Rivera y Urquijo, who was a grandson of a former dictator and later helped Spain become a democracy. The Oriol family is still very well-known in Spanish society and business today.

In the Spanish Civil War

Antonio's family had a long history of supporting Traditionalism. During his student years in Madrid, Antonio was active in the Carlist student group, Agrupación Escolar Tradicionalista. He also joined the paramilitary group called Requeté when he was a teenager.

In the spring of 1936, Oriol was involved in the Carlist plan against the Spanish Republic. On July 18, he was in Vitoria when the military uprising began. The city was quickly taken by the rebels. Oriol joined the requeté troops that took San Sebastián in September. Later that month, he joined the 2nd Requeté Company, which was part of the 3rd Battalion of the Flandes regiment. This unit was sent to the mountains north of Vitoria.

In October 1936, his unit fought hard on the Isusquiza hill. Antonio was injured and had to leave the front. A few days later, his younger brother Fernando was fatally wounded in the same area.

After recovering, Oriol became a provisional lieutenant. He rejoined his unit in December to help unblock Villareal de Alava. In early 1937, his unit fought in the Biscay campaign and later in the battle of Brunete in July. In September, his company was in Cantabria, and during fighting in Asturias, Oriol was leading the 1st Section.

After the Northern campaign, his unit went to Teruel at the end of 1937. Oriol was wounded a second time near Mata de los Olmos in March 1938. After recovering, he rejoined his unit in June at the Castellón front. He led his section during intense fighting in Sierra de Pandols during the Battle of Ebro. For his bravery, he received an individual Military Medal. In December 1938, his company was in Huesca and then took part in the Catalonia offensive in early 1939. In March, he was promoted to captain of infantry and finished the war commanding his unit near Cartagena.

Businessman (1940–1955)

After the Civil War, Antonio Oriol focused on his family's businesses. He was active in several companies controlled by the Oriol family. For example, in the mid-1940s, he was involved with VALCA, a chemical company based in Santander.

His main business focus was on Tren Articulado Ligero Goicoechea Oriol (TALGO). This was a new company started by his father and Alejandro Goicoechea in 1942 to build and operate high-speed trains. Because Spain had problems making the trains, production was done in the United States. Oriol spent time in New York, where he signed a contract with American Car and Foundry and oversaw the building of the Talgo II trains.

In 1950, Oriol became the chief executive officer of TALGO. The company was very important for showing Spain's industrial strength. One of his big tasks was to work out an agreement with RENFE, the state railway company, for using their tracks. In 1950, the first commercial Talgo service started between Madrid and Hendaye.

In 1953, a new agreement was made: TALGO would build and maintain the trains, but RENFE would operate them as their own property. This helped the company pay off its loans and grow. By the 1950s, TALGO trains were running on many routes across Spain. Oriol left his position as chairman in the mid-1950s to take on political roles, but he remained on the company's new management committee.

Welfare and Social Work (1955–1965)

In 1955, Oriol was chosen to be part of the FET National Council, which meant he also became a member of the Cortes Españolas, Spain's parliament. Around this time, he was also appointed as the National Delegate for Social Aid for FET and became president of Cruz Roja Española (the Spanish Red Cross).

In early 1957, he was named Director General of Welfare and Social Works, a department within the Ministry of Interior. He likely got this position because of his connection with Camilo Alonso Vega, who had just become the Minister of Interior. Alonso Vega had been Oriol's military superior during the Civil War.

Oriol's department focused on improving Spain's social security system. Before this, social support was basic and managed by different groups. Starting in 1959, it began to be set up as a modern state welfare system. In 1960, new funds were created, and local welfare boards reported to civil governors. The system was further improved with new laws, including the Social Security Basic Law adopted in 1963. This law created two types of social security: "basic protection" and "additional protection." This made Spain's social security system similar to those in other Western European countries.

Oriol often appeared at official events, like opening hospitals or child care centers, or inspecting local welfare offices. He also started campaigns, such as one in 1963 against illiteracy (not being able to read or write) for the Spanish Red Cross. He also quietly supported the idea of Don Juan becoming the future king of Spain.

Minister of Justice (1965–1973)

In 1965, Oriol was appointed Minister of Justice. This position had often been held by Traditionalists since 1938. His appointment was part of Franco's way of balancing different political groups. Oriol's first major project was working on the 1966 Organic Law of the State. This law organized and clarified existing rules and made some small changes. Oriol supported it, saying that the government was always improving.

A big part of Oriol's work involved issues with the Church. He helped create the law on religious freedom. This law caused some tension, especially among Traditionalists. Oriol said the law respected civil rights but did not break up Catholic unity. The law was passed in 1967.

From the late 1960s, he was involved in talks about a new agreement with the Vatican. This was a difficult issue because the Spanish Church was becoming more opposed to Franco's government. Oriol did not want changes that would reduce the state's power. He also dealt with the increasing number of priests charged with political offenses. In 1968, Oriol set up a special prison in Zamora just for religious people. He spoke out against "Marxist influence" among the clergy and was upset by some public statements from Church leaders.

As minister, Oriol oversaw a gradual easing of penal policy (rules about punishment). He stated that Spain had one of the lowest prison populations in the world. The number of prisoners went down, and fewer death penalties were carried out. Over 10 years, there were 13 executions and 19 cases where sentences were reduced. However, in the early 1970s, Oriol admitted there were 3,000 political prisoners. These prisoners were all granted amnesty (a pardon) in 1971. During his time, he also helped pass a law that partly reformed and combined the civil and criminal laws.

Some historians see Oriol as more of a technocrat (someone who focuses on technical details) than a politician. He was not a major player in power struggles, but he had Franco's trust. He worked to counter the actions of some Carlist groups. As minister, he denied Spanish citizenship to Don Javier and tried to show that all Traditionalists supported the government. His efforts to support the monarchy were successful when Don Juan Carlos was officially declared the future king in 1969.

Council of State: Franco's Final Years (1973–1975)

In July 1973, Oriol left the Ministry of Justice. Franco appointed him to the Consejo de Estado, a high advisory body. He also became its president, which gave him a seat in the Council of the Realm, another important council. This made him one of the highest-ranking "carlo-francoists" (people who supported both Carlism and Francoism).

During 1973-1975, Oriol attended many official events, gave lectures, and participated in meetings related to his roles in these councils. These activities were often reported in the news. He often spoke about his belief in the strength of the Francoist system, even as Franco's health was clearly declining. Some of his speeches hinted at the need for understanding among all Spaniards and spoke against dividing people into winners and losers. Many of his statements pointed to Don Juan Carlos as the key person for Spain's future.

In Franco's last years, Oriol supported the idea of "political associations," which were groups that could help organize political ideas. He tried to create a Traditionalist group that supported the government. In 1974, Oriol attended a traditional Carlist celebration. In early 1975, he tried to organize a "Traditionalist summit." After new laws on political associations were passed, his organization, Union Nacional Española (UNE), was formed in mid-1975, with Oriol as one of its leaders. This group included Carlists who had joined Franco's government and other politicians who hoped that Juan Carlos's monarchy would keep the system going, perhaps with small changes.

Council of State: Spain's Transition to Democracy (1975–1979)

After Don Juan Carlos became king, Oriol helped the new king in his efforts to give power to more liberal politicians. In December 1975, Oriol said the Francoist system was well-organized. But in April 1976, he admitted that "Francoism could not work without Franco." However, he imagined the change as a slow evolution, not a sudden break. He was against having many political parties and wanted to build a system of associations within the existing political movement. He was very active in developing the UNE group and became president of its advisory council in April 1976.

Some people saw Oriol as a representative of the hardline "búnker" (a term for those who wanted to keep the old system). In response, he said he was committed to evolution and against big changes. He urged the government not to deal with people who wanted to break up the system and showed his loyalty to Franco's memory. In May 1976, Oriol was involved in an event at Montejurra that aimed to block a rally by another Carlist group. This event resulted in the deaths of two people.

In June 1976, Oriol supported the appointment of Adolfo Suarez as the new prime minister. He continued to oppose legalizing political parties and insisted on loyalty to the existing political principles. He tried to shape the draft election law accordingly. He later resigned from the UNE executive because his membership in the Council of the Realm was not compatible with it.

In December 1976, Oriol, who was theoretically the fourth most important person in the kingdom as president of the Council of State, was kidnapped by a terrorist group called GRAPO. His captors said he was a symbol of Franco's government and demanded that left-wing political prisoners be released in exchange for him. This kidnapping made people worry that the government was losing control. However, after two months, on February 11, 1977, Oriol was rescued by Spanish security forces in a raid on a GRAPO hideout in Alcorcon.

When the last Francoist parliament was dissolved in 1977, Oriol lost his seat. He did not take part in the June elections for the new assembly. At this time, he was becoming less central to politics. His activities in 1977 and 1978 were mostly official duties in the two Councils he belonged to, which had little political power. His public statements showed he was becoming more detached and disappointed. He lost his seat in the Council of the Realm when it was ended by the new constitution in 1978. Having reached the normal retirement age, Oriol stopped being president and member of the Council of State in 1979. He continued to show respect for Franco and attended many events honoring Franco and other officials from that era.

Retirement (After 1979)

After losing all his government and party positions in 1979, Oriol retired from politics. However, he remained involved in organizations for former soldiers. In 1980, he was president during a meeting of Derecha Democrática Española, a short-lived center-right group. Some historians believe he was active behind the scenes in a plan to remove Prime Minister Suarez and replace him with a military leader. After the failed coup attempt of 1981, some media said he was a political supporter of Antonio Tejero, a leader of the coup. Oriol sued them for libel (false statements that harm someone's reputation). Others thought it was unlikely he would be involved in such a plot, given his long history of supporting Juan Carlos.

In the 1980s, Oriol appeared in public at various post-Francoist events. He always attended anniversary rallies for Franco's death and funerals of other officials from that time. He also served as vice-president of the Francisco Franco National Foundation. As president of an organization for provisional lieutenants in 1985, he protested against anti-Franco speeches by some state officials, saying they would "break national harmony." In 1986, he spoke about "the idea of reconciliation that should guide the future of the Homeland" and against "revenge that some parts of Spain intend to renew."

Oriol continued to serve on the boards of various companies related to his family's business group. These included Argón, Compañía Minero-Metalúrgica Los Guindos, Electra de Viesgo, Electricista Alcoyana, Fuerzas Eléctricas del Noroeste, Iberdrola, Patentes Talgo, and Vidrieras de Llodio. He sometimes appeared in public for business events, such as when the Madrid-Paris TALGO connection was opened. He began to step back from his business roles in the late 1980s. He resigned from his main position on the board of Iberdrola in 1990, and his son took his place.

In the 1990s, Oriol was mainly seen in public because of his leadership of two ex-combatant organizations. Although he had disagreements with another politician, Blas Piñar, some of their rallies still attracted many people. His death was reported in most national newspapers. Some articles spoke respectfully of him and listed his many awards, while others mentioned the old rumors about his possible involvement in the 1981 coup attempt.

See also

In Spanish: Antonio María de Oriol para niños

In Spanish: Antonio María de Oriol para niños

- Carlism

- Carlo-francoism

- Traditionalism (Spain)

- Francoism

- Jose Maria de Oriol y Urquijo

- Jose Luis de Oriol y Uriguen