Battle of St. Michaels facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of St. Michaels |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| George Cockburn | Perry Benson | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Royal Navy * 1st Bn Royal Marines * 2nd Bn Royal Marines British Army * 102nd Regiment of Foot |

12th Maryland Brigade * Parrott Point Gun Battery * Dawson's Wharf Battery * Easton Vol. Artillerists |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Land: 300 Sea: unknown |

Land: 500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 29 | 0 | ||||||

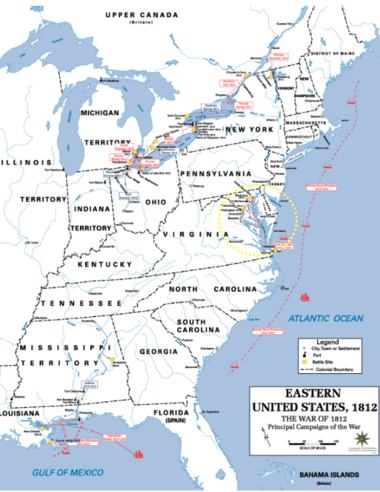

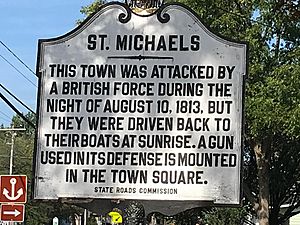

The Battle of St. Michaels happened on August 10, 1813, during the War of 1812. British soldiers attacked American militia in St. Michaels, Maryland. This town is on Maryland's Eastern Shore. It has access to the Chesapeake Bay.

At that time, St. Michaels was a key shipping spot. It was on the main route to important cities. These cities included Baltimore and Washington, D.C.. Even though St. Michaels was small, it was important. The British wanted to attack it because of its shipbuilding. It was also connected to Easton. Easton was the biggest town in that part of Maryland.

St. Michaels is on the St. Michaels River, now called the Miles River. Smaller boats could use this river. They could get within 3 miles (5 km) of Easton. The British attacked St. Michaels early in the morning. They arrived before sunrise.

The British quickly took over an artillery battery (a group of cannons). Then they went back to their boats. As they moved their flotilla (group of small boats) closer, two other groups of cannons fired at them. These cannons were operated by local militia. A large boom (a barrier) was placed across the harbor. This stopped the British from getting closer.

The British fired back, but they eventually left. They went back to their base on Kent Island in Maryland. The people of St. Michaels had no injuries. The British had some injuries and at least one boat was damaged. A local story says that the townspeople hung lanterns in trees. This tricked the British gunners. They fired their cannons over most of the town's buildings.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The United States declared war on the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on June 18, 1812. Not everyone in the U.S. agreed with this decision. Some people, like the Federalists, were against the war. They were bankers and businessmen. But the Democratic-Republican Party had more members. They believed the war was necessary.

After the war started, the British government blocked American ports. This meant ships could not easily enter or leave. They made this blockade stronger in 1813. British ships were sent to close ports like New York. They also closed ports further south, including those on the Chesapeake Bay.

In February 1813, British ships took control of Hampton Roads. This is at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. This stopped all ship traffic in and out of the bay. It closed major ports like Norfolk in Virginia and the Port of Baltimore in Maryland.

British Raids on Towns

Starting in spring 1813, Rear Admiral George Cockburn led raids on towns along the Chesapeake Bay. These raids involved destroying or taking property. This included crops and farm animals. On May 3, Cockburn burned most of Havre de Grace, Maryland. Other Maryland towns, Georgetown and Fredericktown, were burned on May 6.

First Lady Dolley Madison called Cockburn's raids "savage." Cockburn even threatened to capture her. He said he would parade her through London. Cockburn had a rule: if a town had no guns or militia, he would leave it alone.

Vice Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren was Cockburn's boss. He was based in Bermuda. Warren felt he did not have enough ships to block the American coast. In May, he got two groups of marines and more ships. He announced that New York and the Mississippi River were officially blocked. He also listed ports in South Carolina and Georgia as blocked. Royal Marines were sent to the Chesapeake Bay. This was because of its naval supplies, ships, and shipyards. Norfolk, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. were important targets.

Who Fought in the Battle

The British Forces

Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren was the main commander for the British in North America. Rear Admiral George Cockburn reported to him. For the attack on St. Michaels, Cockburn had eight ships. He also had 45 barges (small boats). His forces included two groups of Royal Marines and an army regiment.

The soldiers who landed on shore were led by Lieutenant James Polkinghorne. He was from the Royal Navy. After the battle, he sent a report to Commander Henry Loraine Baker. Baker commanded HMS Conflict, a sloop (a small warship) with 10 to 12 cannons. The British used barges to reach the shore. These barges were moved by oars and small sails. Each barge had a small cannon called a "carronade".

The American Forces

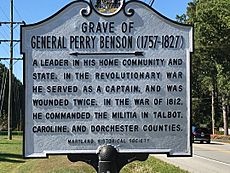

The United States had few federal troops near St. Michaels in 1813. Most of the fighting was done by state militia. Maryland's militia was organized into groups. Brigadier General Perry Benson led the militia from Talbot, Caroline, and Dorchester counties. He was a veteran of the American Revolutionary War.

At the Battle of St. Michaels, Benson's force had about 500 men. They included two regiments, several cavalry companies, and three artillery batteries (groups of cannons).

- 12th Maryland Brigade: Led by Brigadier General Benson.

- 4th Maryland Regiment: Led by Lieutenant Colonel William B. Smyth. Most men were from Easton.

- 26th Maryland Regiment: Led by Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Auld. Men were from the St. Michaels area.

- 9th Cavalry District: Led by Lieutenant Colonel Edward Lloyd.

- Two artillery batteries: A third battery was part of the 4th Maryland Regiment.

Benson's group was large, but their training was not very good. They also did not have enough weapons. Cannons were used by the artillerists (cannon operators).

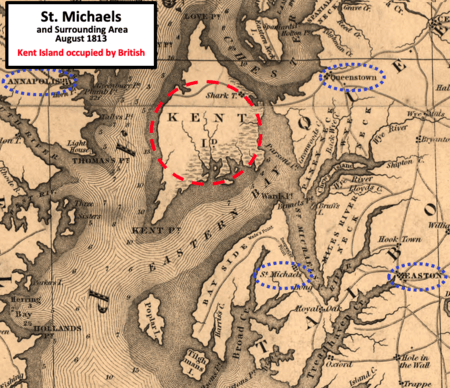

Getting Ready for Battle

The British captured Kent Island in Maryland in early August 1813. This island is north of St. Michaels. It is across the bay from Annapolis, Maryland's state capital. The British landed about 3,000 men on the island. They met no resistance because most people had left.

Kent Island had food and fresh water. It was a good base for attacking Maryland's Eastern Shore. It was also good for attacking Annapolis, Baltimore, and Washington.

During this time, British ships were in Eastern Bay. This is between Kent Island and St. Michaels. This caused alarm in Talbot County. St. Michaels was a target because it built ships. At least six ships were being built there. It was also a port for Easton, the largest town on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Easton had the only armory (weapon storage) in the area. It also had a bank and many goods the British could take.

Boats could use the St. Michaels River to get close to Easton. Another water route to Easton, Tredhaven Creek, was protected by a six-gun battery called Fort Stokes.

Preparing the Defenses

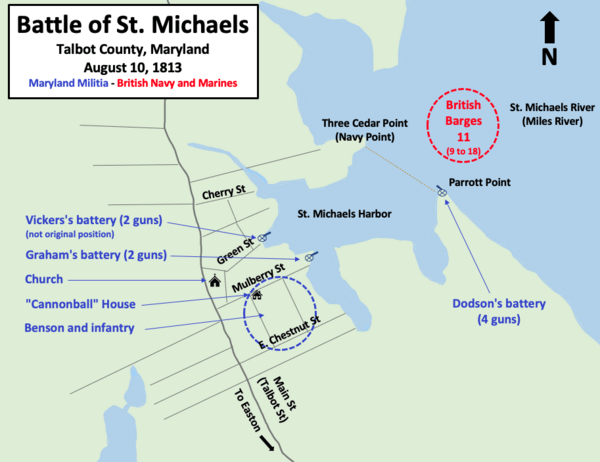

Militia from all over Talbot County came to St. Michaels. They joined the local infantry company, the Saint Michaels Patriotic Blues. Captain Joseph Kemp led this company. Lieutenant William Dodson led the artillery men. Kemp's company and some Easton companies wore uniforms. About 500 militia troops gathered. They were led by Brigadier General Benson, Colonel Auld, and Colonel Thomas Jones. The men stayed in the town's two churches.

Benson set up three artillery batteries around the town. East of town, Dodson commanded 30 men. They had four cannons behind a small fort. This was at Parrott's Point. It was at the mouth of the town's harbor. A boom was placed across the harbor entrance. This was to stop enemy ships.

Inside the town, at Dawson's wharf, was a two-gun battery on wheels. John Graham commanded it. Two more cannons were placed outside town. These were in case the British landed behind the town. Lieutenant Clement Vickers commanded this battery.

Sentries (watchmen) were placed at different spots. They watched the British on Kent Island. A British ship was seen checking out the area north of town. A deserter (someone who left the British side) came to Bayside. He said the British planned to attack St. Michaels soon. But they were worried about what they thought was a 10-gun battery.

The Battle Begins

Early on August 10, about 300 British soldiers and marines moved up the St. Michaels River. They were in nine to eighteen barges. The river was over 1 mile (1.6 km) wide. They traveled in fog and darkness along the shore opposite St. Michaels. The sentries on the St. Michaels side did not see them.

The British crossed the river around 4:00 AM. They arrived near Parrott's Point in the fog. They got out of their boats in the water. They were near Dodson's cannons. An African American man named John Stevens discovered them.

Dodson's men were surprised and panicked. Most dropped their weapons and ran through a cornfield back to town. The British fired their muskets at them. Only Dodson, Stevens, and a third man stayed with the cannons. They managed to move one cannon. It was loaded with cannonballs and canister shot (small metal balls). They fired it at the British. The British expected to take the cannons easily. Instead, they were hit by the cannon. Despite injuries, they kept going. Dodson and his two men then ran. The cannons were captured and disabled.

After disabling the cannons, the British went back to their barges. They took their dead and injured with them. The barges moved closer to town. They were less than half a mile (0.8 km) away. But they could not cross the boom that had been placed earlier. They fired two cannons at the town. Then they moved further out into the river. They kept firing "with much vigor" (force).

A St. Michaels story says that the town hung lamps in trees. This confused the British. It made them fire over the town. Graham's battery at Dawson's wharf fired back. They fired 10 shots. The Easton artillerists heard the cannons. They moved their battery to Mill Point in town. They fired five shots as the British started to leave.

By 9:00 AM, the cannon fight was over. The British went back to their base. Benson, his infantry, and his cavalry were waiting in the town square. They had more men than the British. But they did not need to fight. The town was successfully defended. It did not suffer the same fate as Havre de Grace.

Injuries and Damages

Lieutenant Polkinghorne reported that his British ground force had "only two wounded." Benson's report said that "some of the houses were perforated" (had holes). But he said there was no "injury to any human being." He also suggested the British had injuries. He mentioned "much blood on the grass at the water" where the British boats were.

A deserter from the Royal Navy said the British had one captain, one marine lieutenant, and twenty-seven soldiers injured or killed. He also thought one of the barges was badly damaged. Another deserter believed one of the British dead was an officer.

What Happened Next

The British threatened St. Michaels again on August 26. This time, they sent 2,100 men in 60 barges. They landed about 6 miles (10 km) north of town. 1,800 British men met 500 Talbot County militia. This group included infantry, cavalry, and artillery. This was the biggest battle on Maryland's Eastern Shore during the war. It lasted only a few shots because the British left.

Warren reported that he had problems with soldiers leaving the army. He also had problems with poor discipline among the marines. His men started getting ready to leave Kent Island on August 22. They decided that attacking Annapolis and Baltimore was a bad idea. Those American cities had received many more soldiers. Warren also wanted to sail to Halifax, Canada, before hurricane season. By September, Warren went to Halifax. Cockburn went to Bermuda. A small group of ships stayed at the Virginia Capes to keep the blockade.

Stories and Legends

Lieutenant Polkinghorne of the British Royal Navy said he felt his mission was "fulfilled." He did not see any ships being built. One reason the British attacked St. Michaels was to destroy ships. He captured a cannon battery and destroyed its ammunition.

But a deserter said the mission was a failure. He said the British leader expected to meet weak militia. Instead, he had too few men to fight against trained soldiers. Shots from the British cannons usually went high. They hit the roofs or upper parts of some houses. Warren's report to John W. Croker on August 23 mentioned an attack on Queenstown. But he did not mention St. Michaels.

The American artillerists were said to be better than the British. Besides the blood found where the British landed, one newspaper said three barges were hit by American cannon fire. Benson's report said the "militia generally behaved well." He did not mention that some ran away. For years, two Easton companies argued about how they fought in the battle.

The local story about the battle is that townspeople hung lanterns high in trees. This tricked the British into firing over the town. Some even say that only the house of shipbuilder William Merchant was hit. This house is now called the Cannonball House. However, Benson's report said "Some of the houses were perforated." He did not mention any trick. It was probably already daylight when the British fired at the town. This makes the legend less likely.

Preserving History

The St. Michaels Historic District has over 300 old buildings. William Merchant's home, the Cannonball House, is part of this district. It has also been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1983. The battle is also remembered by the Star-Spangled Banner National Historic Trail. Two local museums talk about the battle: the St. Michaels Museum at St. Mary's Square, and the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Images for kids