Bert Corona facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

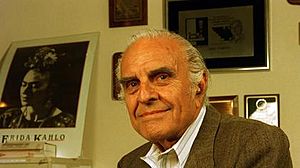

Humberto N. Corona

|

|

|---|---|

in 1997, by Lori Shepler

|

|

| Born | May 29, 1918 |

| Died | January 15, 2001 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | Mexican-American |

| Occupation | Labor movement and civil rights leader |

Humberto Noé Corona (May 29, 1918 – January 15, 2001) was an American leader for workers' rights and civil rights. He worked with many important Mexican American groups. He also helped start several of them. Bert Corona helped workers join unions and fought for the rights of immigrants. By the 1960s and 1970s, during the Chicano Movement, people knew him as El Viejo ("the Old Man"). He was a respected and experienced activist.

Contents

His Early Life and Family

Bert Corona's father, Noé Corona, was a commander in Pancho Villa's army during the Mexican Revolution. He joined the fight after his family was hurt in a terrible event in Chihuahua, Mexico. Noé Corona believed in workers' rights and freedom.

His mother, Margarita Escápite Salayandía, was a schoolteacher from Chihuahua. Her mother, Bert's grandmother, was a doctor. In 1914 or 1915, his family moved to El Paso, Texas. They settled in a Mexican neighborhood called El Segundo Barrio. Bert and his three siblings were born there.

In El Paso, his father worked in logging and rock cutting. He also secretly continued his revolutionary work. The family returned to Chihuahua, Mexico, in 1922. His father became a forest ranger. Sadly, he and other former soldiers were killed while fighting a forest fire. Bert believed they were murdered because the government feared them. After his father's death, Bert's family moved back to El Paso. Growing up, Bert heard many stories about the Revolution. His mother and grandmother's Protestant community also influenced him. He said that religion was very important in shaping his later political actions.

His School Days

Bert Corona started school in Mexican Protestant kindergartens. Then he went to public school. He was good at English, which his mother had taught him. He stayed in Texas public schools until fourth grade. His mother then sent him to Harwood Boys School in Albuquerque, New Mexico. She was upset about how Mexican-American students were treated.

At Harwood, Bert learned discipline but also faced racism. Students were punished for speaking out against unfair coaches. They also disliked how Mexican history, like the Mexican–American War and Pancho Villa, was shown negatively. So, the students went on strike! They refused to go to classes. Because of this, the school stopped the expulsions and made the coach apologize.

He returned to El Paso for high school. He went to the "Mexican" (segregated) Bowie High School. Later, he attended El Paso High School, which was a "White" school that had started to accept some Mexican students. Bert, as he was now called, played basketball for three years. He saw how the Great Depression affected Mexican families who were forced to return to Mexico or those who moved because of the Dust Bowl. His grandmother often helped these people.

In high school, he became interested in social justice. He read books by writers who exposed problems in society. He also joined a discussion group about workers' rights. He and other Mexican students worked together to elect the first Mexican student body president at El Paso High.

After high school in 1934, Bert worked in a drug store and played basketball. In 1936, he received a scholarship to the University of Southern California (USC). He moved to Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in East Los Angeles. He volunteered with El Salvador Church, helping to organize for better housing.

In Los Angeles, Bert learned about groups like the International Workers Order. These groups pushed for government help for people. He also listened to speakers who talked about workers' rights and freedom.

At USC, Bert studied law. He hurt his ankle early on, so he focused on his studies. He joined a student group that helped lower-class students. This group soon became very important in school politics.

By 1937, Bert was involved with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a large union group. He decided he liked helping workers more than playing basketball. He stayed in school and joined the Mexican American Movement (MAM). This group of college students worked on issues like unfair education for Mexican Americans and police brutality. MAM stopped when the United States entered World War II, as many members joined the military.

Working with Unions

While at USC, Bert worked for a drug company. He and his coworkers supported a strike by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). The longshoremen won their demands. This inspired the drugstore workers to form their own union. They joined the ILWU. Bert was elected recording secretary. He learned a lot about organizing from Lloyd Seeliger. In 1940, Bert became the head of his union local's strike committee. In 1941, he was elected president. Soon after, he was fired because of a slowdown organized by someone else. Harry Bridges, the head of the ILWU, then offered Bert a job as a CIO organizer.

With the CIO, Bert helped workers in the waste material industries form unions. He also reached out to young Mexican Americans, called Pachucos, who helped the union. As the CIO organized workers, Bert helped these young people find jobs. This created a strong bond between them.

In the 1940s, the CIO worked with Luisa Moreno's Spanish-Speaking People's Congress. This group supported Spanish-speaking people in the U.S. The Congress was different from other groups. It believed that all Spanish-speaking people, whether U.S. citizens or not, should be united. An attack on one group was an attack on all. This idea of unity made the Congress very popular.

The Congress and the CIO worked together on workers' rights, police brutality, unfair schools, and access to public places. One big campaign was defending Mexican American youth accused in the Sleepy Lagoon murder case. Bert Corona was on the defense committee with writer Carey McWilliams and actor Anthony Quinn.

Bert also fought against racism in the justice system. He joined the defense committee for Fetus Coleman, an African American man wrongly accused of a crime. Their efforts helped Coleman go free.

His Marriages

On August 2, 1941, Bert Corona married Blanche Taff in Yuma, Arizona. Blanche was a Jewish-American labor organizer. They met while working to organize aviation workers. Bert said that even though they had different backgrounds, their shared goals brought them together. In the 1930s, young people of all backgrounds joined unions and fought for social change.

The couple moved to Silver Lake, Los Angeles. During World War II, their neighbors supported the Japanese American internment, which meant Japanese Americans were forced into camps. So, the Coronas moved to Mid-Wilshire, Los Angeles. Their new landlord complained when they invited African American union members to visit. He accused them of trying to integrate the neighborhood. He tried to get them evicted. But the Coronas held a party for all their neighbors. They invited their Black friends and their congressperson, Will Rogers Jr.. Rogers' wife, Martha Fall Rogers, who had been Bert's classmate, came. She helped convince the neighbors to drop the petition. The Coronas lived there until Bert joined the army.

Bert Corona later married Angelina Casillas in 1994. He is survived by his children Margo De Lay, Frank Corona, and Ernesto Corona.

During World War II

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Bert volunteered for the United States Army Air Corps. He left his union job. He saw how Mexican-American and Jewish soldiers were treated unfairly during training. He also went to officer training in Cedar City, Utah. The local people, mostly Mormon, did not welcome the soldiers. They worried the soldiers would "corrupt" their daughters. After a town meeting, relations improved.

After a year of training, Bert went to the Santa Ana Army Air Base in Santa Ana, California for flight training. He worked long hours, training and doing office tasks. He also had a psychiatric evaluation to find "deviants." He was labeled "probably patriotic." This label was often given to people from groups whose loyalty was questioned.

Soon after, officers questioned Bert about his political beliefs and union work. He was asked about books like Mission to Moscow and One World. He was questioned again for even longer. He was never told the results, but he was removed from the Air Corps.

Bert was then sent to a hospital in Palm Springs, California. He worked in the mailroom and as a surgical assistant. In Palm Springs, he helped organize discussions for soldiers. These discussions were about racism, religious discrimination, and unfair accusations of being a communist.

Bert then transferred to the Rainbow Division for combat training in Oklahoma. He later transferred to Fort Benning for paratrooper training and became a demolition specialist.

Just before his unit went overseas, Bert asked for a pass to Atlanta. He believes someone tricked him to prevent him from going to combat. Military police stopped him and found his pass was only for Columbus, Georgia. They locked him in a federal prison for over a month. He was not allowed to contact his commander. He became friends with a guard who helped him get a message to his wife and Harry Bridges. This led to his release. He got the "AWOL" (absent without leave) removed from his record, but he was never paid for the time he was in prison.

When it seemed he wouldn't serve overseas, his colonel received a request for people for the United States Army Signal Corps. Bert was sent to Fort Crowder in Neosho, Missouri for training. He was set to go to the Pacific. However, in Neosho, he met Jaime Del Amo, who had worked for Francoist Spain. Del Amo identified Bert as a "subversive" because of his work with the Spanish-Speaking People's Congress. Bert was then sent to a processing center in Northern California, where he stayed until the end of the war. He said he paid the price for being involved in progressive causes.

After the War

After leaving the Army, Bert and his wife settled in East Los Angeles. They lived in the Ramona Gardens housing project. Bert, with others, formed the Mexican-American Committee for Justice in Housing. They worked to open up housing projects to Mexican Americans. Because of their efforts, the housing authority agreed to talk with the Committee.

Bert wanted to return to his union job, but it had been filled. He tried to work as a longshoreman, but he couldn't get the necessary security clearance from the United States Coast Guard.

In 1947, Bert took a job selling diamonds for his father-in-law. He and his family, including his daughter Margo, moved to Mill Valley, California. His two sons, David and Frank, were born there.

Even though he worked in private business, Bert stayed interested in union activities. In the 1950s, it became harder to organize movements. He helped build the Independent Progressive Party in the San Francisco Bay Area. He then joined the Community Service Organization (CSO). He agreed with their goals, but he didn't like that they wanted to keep "reds" (communists) out. He knew they meant Mexicans involved in certain groups. The CSO helped people register to vote. This led to the election of Assemblyperson Byron Rumford, one of the first African Americans elected to that body. The CSO also worked on affordable housing, police brutality, and access to public services.

Bert first met César Chávez in the late 1940s or early 1950s. Chávez spoke at a conference, and Bert was impressed by his honest and practical approach.

Working with ANMA

While Bert worked with CSO, he was more active with the Asociación Nacional México-Americana (ANMA). He saw ANMA as carrying on the strong, activist traditions of El Congreso. ANMA was supported by independent unions. Bert became the chief organizer for ANMA in Northern California. ANMA's main goal was to help Mexican workers join unions. It also fought against unfair treatment of Mexican workers, like giving them the most dangerous jobs or not promoting them.

In 1951, Bert represented ANMA at a conference for mineworkers in Mexico City. He promoted the cause of striking mineworkers from New Mexico. Their strike was later shown in the 1954 film Salt of the Earth. The film's star, Rosaura Revueltas, had been jailed on immigration charges. At the conference, Bert met mineworkers and organizers from all over Latin America. He also met famous Mexican artists and writers like Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Revueltas (Rosaura's brother). José Revueltas organized a protest at the U.S. embassy in Mexico City to protest his sister's imprisonment. Thousands of students attended, which helped pressure the U.S. to release her.

After the conference, Bert was invited to stay at Rivera and Kahlo's home. At that time, the FBI was watching Rivera's home, especially for American visitors.

The FBI targeted ANMA and its leaders. In 1953, agents visited Bert's home. They asked him to help identify communists in ANMA and other unions. Bert told them to investigate fascists instead, as he believed they were a bigger threat. The FBI contacted him several more times, but Bert refused to cooperate. However, their harassment of other ANMA leaders caused several chapters to close.

MAPA and Immigrant Rights

In April 1960, Bert Corona helped start the Mexican American Political Association (MAPA). This group was formed because people felt the Democratic Party wasn't truly addressing the concerns of Mexican Americans. Bert led MAPA's work in Northern California and was the organization's president from 1966 to 1971.

Bert was also closely involved with Hermandad Mexicana Nacional (HMN). This group focused on organizing unions and helping undocumented workers. He met fellow activist Soledad Alatorre through their work with labor groups. They connected with HMN, which was one of the few Mexican-American organizations run by Mexican Americans. HMN was facing difficulties because of the House Un-American Activities Committee. So, Bert and Alatorre took charge of the organization. In 1968, they moved it to Los Angeles. Its local chapters became known as Centro de Acción Social Autónomo, or "CASA." CASA began working for the rights of immigrant workers. It also provided them with social services, like legal help and education.

From the late 1960s to the 1980s, Bert taught part-time in the new field of Chicano Studies at California State University, Northridge and California State University, Los Angeles.

In 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. invited Bert Corona, along with Corky Gonzales and Reies Tijerina, to Atlanta. They planned for the March on Poverty. Sadly, King was assassinated before the march happened.

Bert Corona taught Chicano Studies at California State University – Los Angeles from 1970 to 1982, when he was dismissed.

One of Bert Corona's most important contributions was teaching people that immigrant workers were a big part of the U.S. workforce, not just a temporary group. His efforts and CASA's work helped unite immigrant workers and U.S.-born Mexican Americans.

As a founder and leader of Hermandad Mexicana Nacional, he played a key role in getting an amnesty program for undocumented workers in the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA). Bert Corona continued to organize with labor unions to change immigration policy. Partly because of his efforts, the AFL-CIO (a large union federation) changed its policy on immigration in 2000. Some unions then started to change how they worked to help immigrant workers.

See also

- List of civil rights leaders

- Soledad Alatorre

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |