Central Alaskan Yupʼik facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Central Alaskan Yupik |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yupʼik Yugtun, Cugtun |

||||

| Native to | United States | |||

| Region | western and southwestern Alaska | |||

| Ethnicity | Central Alaskan Yupik people | |||

| Native speakers | 19,750 (2013) | |||

| Language family |

Eskimo–Aleut

|

|||

| Dialects |

Yugtun (Yukon-Kuskokwim)

Cupʼik (Chevak)

Cupʼig (Nunivak)

|

|||

| Writing system | Latin, formerly the Yugtun syllabary | |||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | ||||

|

||||

|

||||

Central Alaskan Yupʼik (also called Yupik or Yugtun) is a language spoken by the Central Alaskan Yupik people in western and southwestern Alaska. It's part of the larger Yupik family, which is a branch of the Eskimo–Aleut language group. The Central Alaskan Yupik people are the largest group of Alaska Natives in terms of population and the number of people who speak their language. In 2010, Yupʼik was the second most spoken native language in the United States, after Navajo. It's important not to confuse Central Alaskan Yupʼik with other related languages like Central Siberian Yupik or Naukan Yupik, which are spoken in Russia and on St. Lawrence Island.

Yupʼik is a very special kind of language called polysynthetic. This means that words are often very long and can carry as much meaning as a whole sentence in English. It builds words by adding many small parts, called suffixes, to a main word part. This language also has three ways to show how many of something there is: one (singular), two (dual), and more than two (plural). Unlike English, Yupʼik doesn't use words like "a" or "the," and it doesn't have grammatical gender (like masculine or feminine).

Contents

What is the Yup'ik Language Called?

The Yup'ik language has a few different names. Because it's located in the middle of other Yupik languages and spoken in Alaska, it's often called Central Alaskan Yupik. The name Yup'ik [jupːik] is what the people who speak it call themselves and their language. It means "genuine person." In some areas, people use other names like Cup'ig on Nunivak Island or Cup'ik in Chevak. These names sound a bit different but mean the same thing as Yup'ik. In the Yukon-Kuskokwim region, the language is called Yugtun.

Where is Yup'ik Spoken?

Yupʼik is mainly spoken in southwestern Alaska. This area stretches from Norton Sound in the north down to the Alaska Peninsula in the south. To the east, it reaches Lake Iliamna, and to the west, it includes Nunivak Island. Other Yupik languages are spoken nearby, like Alutiiq to the south and east, and Central Siberian Yupik to the west. The Iñupiaq language is spoken to the north, but it's quite different from Yupʼik, like how Spanish and French are different.

Out of more than 23,000 Yupik people, over 14,000 still speak the language. In 17 out of 68 Yupik villages, children still learn Yupʼik as their first language. These villages are mostly found along the lower Kuskokwim River, on Nelson Island, and near the coast between them. However, the way younger generations speak Yup'ik is changing because of English. Their language might have fewer complex word structures and more English words mixed in.

What are the Yup'ik Dialects?

Yup'ik has five main dialects, which are like different versions of the language. They are: Norton Sound, General Central Yup'ik, Nunivak, Hooper Bay-Chevak, and the Egegik dialect, which is no longer spoken. Even though there are differences in sounds and words, people speaking different Yup'ik dialects can usually understand each other. Sometimes, people are very proud of their own dialect and prefer not to use words from other dialects.

Here are the main Yup'ik dialects and some of the places where they are spoken:

- Norton Sound (also called Unaliq-Pastuliq): Spoken around Norton Sound.

- General Central Yupʼik (Yugtun): Spoken on Nelson Island, in the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta, and in the Bristol Bay area. This is the most common dialect.

- Core dialects: Spoken on the lower Kuskokwim River, the coast up to Nelson Island, and in Bristol Bay.

- Lower Kuskokwim sub-dialect: Spoken in many villages like Akiachak and Bethel.

- Bristol Bay sub-dialect: Spoken in places like Aleknagik and Dillingham.

- Peripheral dialects: Spoken on the upper Kuskokwim River, on the Yukon River, and around Lake Iliamna.

- Mixed dialects: These share features from both core and peripheral varieties.

- Core dialects: Spoken on the lower Kuskokwim River, the coast up to Nelson Island, and in Bristol Bay.

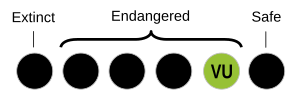

- Egegik: This dialect is now extinct.

- Hooper Bay-Chevak:

- Hooper Bay sub-dialect: Spoken in Hooper Bay.

- Chevak sub-dialect: Spoken in Chevak.

- Nunivak: Spoken in Mekoryuk. This dialect is quite different from the mainland Yupʼik dialects.

Even within these sub-dialects, there can be small differences in how words are said or what words are used. For example, here's how some words differ between the Yukon and Kuskokwim sub-dialects of General Central Yupʼik:

| Yukon (Kuigpak) | Kuskokwim (Kusquqvak) | meaning |

|---|---|---|

| elicar- | elitnaur- | to study or to teach someone |

| elicaraq | elitnauraq | student |

| elicarista | elitnaurista | teacher |

| aiggaq | unan | hand |

| cella | ella | weather, outside, universe, awareness |

Writing and Literature

Around 1900, a Yupik speaker named Uyaquq created a special writing system for the language called the Yugtun script, which used symbols for syllables. Today, however, Yupʼik is mostly written using the Latin alphabet, which is the same alphabet English uses.

Early efforts to write Yupʼik were made by missionaries. In the 1960s, the Alaska Native Language Center helped create a modern way to write the language. This led to the first bilingual school programs in Yupʼik villages in the early 1970s. Since then, many books and materials have been published in Yupʼik, including a big dictionary and grammar books by Steven Jacobson, and stories and novels by other writers like Anna Jacobson.

How Yup'ik Words are Built

Yup'ik words are very long and complex because they are built by adding many small parts together. Think of it like building with LEGOs! Each small part, called a morpheme, adds a specific meaning or changes the word.

A Yup'ik word usually starts with a stem, which is the main part that gives the word its basic meaning. After the stem, there can be one or more postbases. These postbases are like special LEGO pieces that can change the word's meaning or even turn a noun into a verb, or a verb into a noun! For example, in Yup'ik, there are no separate words for adjectives like "good" or "big"; instead, these ideas are built into the nouns or verbs using postbases.

Finally, at the end of the word, there's an ending. This ending tells you important things like who is doing the action (for verbs) or how the word is used in the sentence (for nouns). Sometimes, an extra small part called an enclitic can be added at the very end. These enclitics show how the speaker feels about what they are saying, like if they are asking a question or just reporting something.

Here are some examples of how Yup'ik words are built:

- The word angyarpaliyukapigtellruunga means "I wished very much to build a big boat."

- angyar is the stem for "boat."

- Then, many postbases are added to mean "big," "make," "wish," "very much," and "past tense."

- Finally, the ending tells you "I" am the one doing the wishing.

- The word kipusvik means "store."

- kipus is the stem for "buy."

- -vik is a postbase that means "place for." So, a store is literally a "place for buying."

Because of these postbases, a word can change its type many times. For example, the word neqe- means "fish" (a noun). But if you add the postbase -ngqerr, it becomes neqe-ngqer-tua, which means "I have fish" (now a verb!).

Verb Changes

Yup'ik verbs change their form depending on who is doing the action and the "mood" of the sentence. Moods show the speaker's attitude or purpose, like if they are making a statement, asking a question, or giving a command. Yup'ik has many moods, some for main sentences and others for connecting ideas, like saying "because" or "if."

Noun Changes

Yup'ik nouns also change their form to show if they are singular, dual, or plural, and how they relate to other words in the sentence. This is called "case." For example, the way a noun is marked tells you if it's the one doing the action or the one receiving the action. This is different from English, where word order usually tells you that.

For example, in Yup'ik, the sentences Qimugtem keggellrua agayulirta and Agayulirta keggellrua qimugtem both mean "the dog bit the preacher." Even though the word order is different, the special ending on "dog" (-m) tells you it's the one doing the biting. To say "the preacher bit the dog," you would change the endings to show that the preacher is now the one doing the biting.

Yup'ik also has many ways to describe where something is located or how it moves. It has special words that show if something is upstream, downstream, near the speaker, far away, or even if it's inside or outside.

Learning Yup'ik

Efforts have been made to teach Yupʼik in schools. In 1972, Alaska passed a law saying that if 15 or more students in a school spoke a language other than English, the school should have a teacher fluent in that language. In the mid-1970s, bilingual education programs started to help keep the Yupʼik language alive. While these laws aimed to help students learn English, they also opened the door for native languages in schools.

Later, in the late 1980s, Alaska Native groups worked to create a policy that would make schools responsible for teaching and using Alaska Native languages, if parents wanted it. A guide for teachers was also created to help them teach Yupʼik to students, comparing it to English to make bilingual education successful.

More recently, in 2018, the first Yup'ik language immersion program in Anchorage started at College Gate Elementary. You can also take Yup'ik language courses at the University of Alaska Anchorage and the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The University of Alaska Fairbanks even offers special degrees in Yupʼik Language and Culture, and certificates for being good at the language.

See also

In Spanish: Idioma yupik de Alaska Central para niños

In Spanish: Idioma yupik de Alaska Central para niños

- Chevak Cupʼik language

- Nunivak Cupʼig language

- Alaska Native Language Center

- Lower Yukon School District (Yupʼik)

- Lower Kuskokwim School District (Yupʼik & Cupʼig)

- Yupiit School District (Yupʼik)

- Kashunamiut School District (Cupʼik)

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |