Cocoliztli epidemics facts for kids

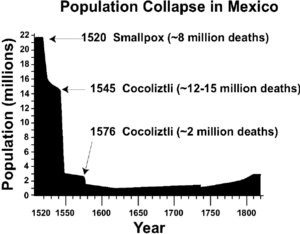

The Cocoliztli Epidemic was a terrible sickness that caused millions of deaths in New Spain (which is now Mexico) during the 1500s. People who got sick had high fevers and bleeding. The Aztec people called it cocoliztli, which means "pestilence" in their language, Nahuatl. This disease spread very quickly across the Mexican highlands. It caused a huge drop in the number of Native people.

Many people think this was the worst epidemic in Mexico's history because so many died. Even today, scientists are not fully sure what caused it. Some recent studies suggest a type of Salmonella bacteria, called Paratyphi C, might have been partly to blame. Other experts believe it was a local viral hemorrhagic fever. This sickness might have been made worse by long periods of drought and poor living conditions. These conditions came after the Spanish conquered the Aztec Empire around 1519.

Contents

History of Cocoliztli

There were at least 12 cocoliztli epidemics. The biggest ones happened in 1545, 1576, 1736, and 1813. Some scientists think a similar sickness might have helped cause the fall of the Classic Mayan civilization long ago. But most experts believe other things, like climate change, were more important then.

Cocoliztli outbreaks often happened within two years after a big drought. For example, the 1576 epidemic followed a drought that reached from Venezuela to Canada. Some scientists think droughts might have led to more rodents. These rodents could have carried the virus that caused the sickness.

The disease mostly affected Native people, but not only them. A Spanish official named Gonzalo de Ortiz wrote that "God sent down such sickness upon the Indians that three out of every four of them perished." Another Spanish missionary, Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, said that 60-90% of everyone in New Spain died. However, most experts now agree that Native people were hit hardest. Africans also suffered greatly. Europeans had lower death rates. A famous European who got cocoliztli was Bernardino de Sahagún. He was a Spanish priest and writer. He got sick in 1546 and again in 1590, when he died.

How the Sickness Spread

The way people lived in Colonial Mexico likely helped the 1545–1548 outbreak spread so widely. After the Spanish conquest, Native people were forced to live in crowded settlements called reducciones. These places were meant for farming and converting people to Christianity. The Native people were already weak from war and other diseases. Their health got even worse in these new crowded places.

The reducciones brought people and animals much closer together. Animals brought from Europe could carry new diseases. The Aztecs and other Native groups had never been exposed to these animal diseases before. This made them very vulnerable. Most common farm animals (except llamas and alpacas) came from Europe.

At the same time, Central America was suffering from severe droughts. Tree-ring data shows that the 1545 outbreak happened during a "megadrought." A lack of water probably made sanitation and hygiene much worse. Big droughts happened before both the 1545 and 1576 outbreaks. Also, short rains during a megadrought could have increased the number of rats and mice. These animals might have carried viruses that cause bleeding fevers. The combination of drought and crowded settlements could explain how the disease spread. This is especially true if the sickness was spread through waste.

Where Cocoliztli Spread

Scientists think cocoliztli started in the southern and central Mexican Highlands. This is near the modern city of Puebla City. Soon after it began, it might have spread as far north as Sinaloa and south to Chiapas and Guatemala. In Guatemala, it was called gucumatz. It might even have reached South America in Ecuador and Peru. But it is hard to be sure it was the exact same disease. The outbreak seemed to stay in higher places. It was almost never found in coastal areas, like along the Gulf of Mexico or Pacific coast.

Symptoms of Cocoliztli

The symptoms of cocoliztli were similar to some diseases from Europe, like measles, yellow fever, and typhus. But many researchers believe it was a different disease. Francisco Hernández de Toledo, a doctor who saw the 1576 outbreak, described the symptoms. These included high fever, bad headaches, dizziness, a black tongue, dark urine, and dysentery (bloody diarrhea). People also had severe stomach and chest pain, lumps on their head and neck, and problems with their brain. They also had yellow skin (jaundice) and a lot of bleeding from the nose, eyes, and mouth.

Some accounts also describe spotted skin and bleeding inside the stomach. This led to bloody diarrhea. The sickness came on very quickly. There were no signs that a person was getting sick before it hit. The disease was very deadly. People often died within a week of their first symptoms. Sometimes, death happened in as few as 3 or 4 days. Because the disease worked so fast, it's hard to find signs of it in old bones. This is because fast-acting diseases usually don't leave marks on bones. Even though they cause a lot of damage to the stomach, lungs, and other body parts.

What Caused Cocoliztli?

Many records from the 1500s describe how devastating the outbreak was. But the symptoms don't perfectly match any known sickness. After 1548, the Spanish started calling the disease tabardillo (typhus). The Spanish had known about typhus since the late 1400s. However, the symptoms of cocoliztli were still not exactly like the typhus seen in Europe. Francisco Hernández de Toledo, the Spanish doctor, insisted on using the Nahuatl word when writing about the disease.

In 1970, a historian named Germaine Somolinos d'Ardois studied all the ideas for what caused it. These included a type of flu, leptospirosis, malaria, typhus, typhoid, and yellow fever. Somolinos d'Ardois concluded that none of these diseases fully matched the descriptions of cocoliztli. He thought it was caused by a "viral process of hemorrhagic influence." This means he believed cocoliztli was not from any known European sickness. He thought it was possibly a virus that came from the New World.

There are stories of similar diseases in Mexico from before the Spanish arrived. The Codex Chimalpopoca says that an outbreak of bloody diarrhea happened in Colhuacan in 1320. If the disease was native to the area, it might have been made worse by the worst droughts in 500 years. The living conditions for Native people after the Spanish conquest also made things worse. Some historians have suggested cocoliztli was typhus, measles, or smallpox. But the symptoms don't quite match.

Later, scientists Marr and Kiracofe looked again at Hernandez's descriptions. They compared them to other diseases. They suggested that scientists should consider New World arenaviruses. These viruses mainly affect rodents. Marr and Kiracofe thought that arenaviruses were not common in the Americas before the Spanish arrived. But rats and mice infestations, brought by the Spanish, might have spread these viruses to people. This happened along with changes in climate and the land. Some later research has focused on the idea of a viral haemorrhagic fever. They are especially interested in how the disease spread geographically.

In 2018, Johannes Krause, a geneticist, and his team found new evidence. They looked at DNA samples from the teeth of 29 skeletons from the 1500s in Mexico. They found a rare type of bacteria called Salmonella enterica (Paratyphi C). This bacteria causes paratyphoid fever. This suggests that paratyphoid might have been the cause of the disease. The team took ancient DNA from the teeth of people buried at a site linked to the 1545–1548 outbreak.

They found Salmonella enterica Paratyphi C in 10 individuals. This type of Salmonella only affects humans. It was not found in soil samples or in people from before the Spanish arrived. Enteric fevers, like typhoid or paratyphoid, are similar to typhus. They were only separated as different diseases in the 1800s. Today, Paratyphi C still causes enteric fevers. If not treated, up to 15% of people who get it can die. This infection is rare now.

A recent discovery of Paratyphi C in a 13th-century cemetery in Norway supports these findings. A young woman who likely died from enteric fever shows the bacteria was in Europe over 300 years before the epidemics in Mexico. So, healthy people who carried the bacteria might have brought it to the New World. There, it spread easily. These carriers might have been used to the bacteria because it's thought that Paratyphi C first spread to humans from pigs in Europe long ago.

However, some scientists, like María Ávila-Arcos, have questioned this evidence. They say that S. enterica's symptoms don't perfectly match the descriptions of cocoliztli. They also point out that other types of germs, like RNA viruses, have not been fully studied. Others note that some symptoms, like bleeding from the stomach, are not seen in modern Paratyphi C infections. More research is needed to find the exact cause of the cocoliztli epidemics. It's also possible that different outbreaks had different causes.

Effects of Cocoliztli

Death Toll

Many people died during the 1545–1548 outbreak. About 800,000 people died in the Valley of Mexico. This led to many Native settlements being left empty. Estimates for the total number of deaths from this epidemic range from 5 to 15 million people. This makes it one of the deadliest disease outbreaks ever.

Other Impacts

The effects of the outbreak were more than just a loss of people. There weren't enough Native workers, which led to a big food shortage. This affected both Native people and the Spanish colonists. The deaths of many Aztecs left a lot of land empty. Spanish colonists quickly tried to take over these lands.

At the same time, the Spanish Emperor, Charles V, wanted to reduce the power of the encomenderos. These were Spanish settlers who controlled Native labor and land. He wanted a fairer system. Around 1549, after the outbreak ended, the encomenderos were losing money. They couldn't meet the demands of New Spain. So, they had to follow new rules called tasaciones. These new laws, known as Leyes Nuevas, limited how much tribute (payments) encomenderos could demand. They also stopped them from having total control over Native workers.

At the same time, other Spanish people started claiming lands that the encomenderos had lost. They also took over the labor of Native people. This led to a new system called repartimiento. This system aimed to give the Spanish government more control over the colonies. It also tried to get more tribute for the government and the king. Rules about tribute also changed because of the 1545 epidemic. The Spanish were worried about future food shortages. By 1577, after years of discussion and a second big cocoliztli outbreak, only maize (corn) and money were allowed as tribute.

Some historians, like Jennifer Scheper Hughes, say that European missionaries were losing hope after years of little success in Mexico. But Native Catholics, surprisingly, turned more to the Church. They found power and their own ways of worship there.

Later Outbreaks

A second major cocoliztli outbreak happened in 1576 and lasted until about 1580. It was not as deadly as the first one, causing about two million deaths. But there are many more detailed descriptions of this outbreak in old records. Many of the symptoms of cocoliztli, like bleeding, fevers, and jaundice, were written down during this epidemic. Spanish records mention 13 cocoliztli epidemics between 1545 and 1642. A later outbreak in 1736 was similar but was called tlazahuatl.

See also

In Spanish: Cocoliztli para niños

In Spanish: Cocoliztli para niños

- Columbian exchange

- Ecological imperialism

- Millenarianism in colonial societies

- Virgin soil epidemic

- Native American disease and epidemics

- History of smallpox in Mexico

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |