Convent of St. Francis, Valladolid facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Convent of St. Francis |

|

|---|---|

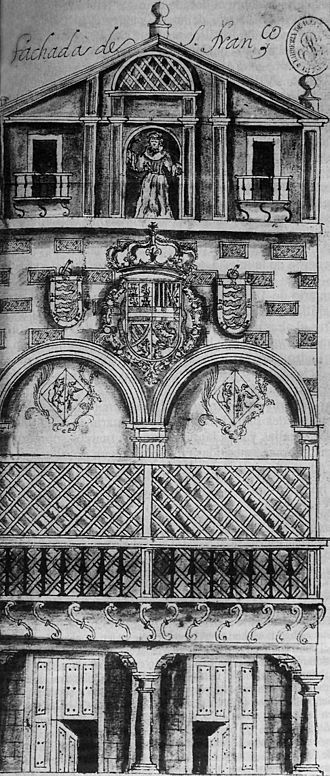

A drawing of the convent's entrance by Ventura Pérez for a history book about Valladolid.

|

|

| General information | |

| Type | Capuchin Convent |

| Architectural style | Gothic |

| Town or city | Valladolid |

| Country | Spain |

| Coordinates | 41°39′06″N 4°43′41″W / 41.651647°N 4.728067°W |

| Construction started | 12th century |

| Owner | Order of Friars Minor Capuchin |

The Convent of St. Francis (in Spanish: Convento de San Francisco) was a very important religious building in Valladolid, Spain. It was started in the 13th century. The convent was built outside the city walls, near a big market square. This market square later became the famous Plaza Mayor.

Queen Doña Violante, who was married to King Alfonso X the Wise, helped and supported the convent a lot. The convent played a huge role in the social and religious life of Valladolid for many centuries. Sadly, it was torn down in 1836. Its large piece of land was then divided and sold. This meant the convent became a lost part of Valladolid's history.

Did you know that Christopher Columbus died in Valladolid in May 1506? He was buried in the church of this Franciscan convent. We don't know exactly which house or hospital he died in. To remember him, the City Council of Valladolid placed a special plaque where the convent used to be. This happened during the 500th anniversary of his death.

Contents

- History of the Convent

- Architecture and Works of Art

- Front Facing the Plaza Mayor

- The Church

- Main Chapel

- Altarpieces

- Grilles

- 1809 Inventory

- Chapel of the Rivera Family

- Chapel of Our Lady of Copacabana

- Altarpiece

- Doors

- 1809 Inventory

- Chapel of St. Anthony of Padua

- Chapel of St. Francis

- Chapels of St. Catherine and St. Charles Borromeo

- Tombs and Other Artworks

- Chapel of St. Anthony the Poor

- Chapel of St. Anne

- Chapel of St. Diego

- Chapel of the Incarnation

- Grille

- Altarpiece

- Chapel of Our Lady of Solitude

- Altarpiece

- Chapel of the Holy Christ

- Inventory

- Chapel of the Incarnation (Second)

- Choir

- News from Historians About the Choir

- 1809 Inventory

- Royal Burials

- Burials of Other Important People

- Nave of Santa Juana (or San Diego)

- Chapel of the Executed or Chapel of the Holy Passion

- Sacristy and Resacristy

- Main Cloister

- Chapel of the Bishop of Mondoñedo

- Chapel of the Venerable Third Order

- The Convent in the 21st Century

- See also

- Images for kids

History of the Convent

The Franciscans, a group of monks, arrived in Valladolid in the early 1200s. The exact date is still debated by historians. The original document that founded the convent is now lost. Historians have tried to figure out the date by looking at other events and the travels of St. Francis himself. He traveled to Spain to start new convents.

A historian named Juan Agapito y Revilla suggests the Franciscans arrived in Valladolid around 1210. He based this on the writings of older historians like Juan Antolínez de Burgos. Antolínez de Burgos wrote in his Historia de Valladolid:

The foundation of the convent of the Lord St. Francis of Valladolid was in the era of 1248, which is the year 1210, by one of the companions of the Saint called Friar Gil, which was two years after his conversion and at the age of 27. [...]

Another historian, Manuel Canesi, also mentions Friar Gil. He says Friar Gil was born in Assisi and was a close friend and follower of St. Francis.

In the early 1900s, a lost manuscript was found. It was called Manuscrito de fray Matías de Sobremonte and was written in 1660. This manuscript, also known as Historia inédita del convento de San Francisco de Valladolid, gave new information. It was found by Antonio de Nicolás and later studied by Agapito y Revilla and José Martí y Monsó. The original manuscript was kept in the library of the Palacio de Santa Cruz. The author, Father Matías de Sobremonte, was a Franciscan monk who studied the history of his order's convents.

Sobremonte mentioned the traditional date of 1210 for the convent's founding. However, he also had some doubts. Today, researchers in the 20th and 21st centuries believe the convent was founded later, around 1230. They all agree on how it started and that it moved in the 1260s.

Starting and Moving the Convent

Queen Berengaria of Castile, wife of King Alfonso IX of León, gave land to the Franciscan monks. This land was in an area called Río de Olmos, possibly around 1230. However, this location was far from the city and not very healthy. It was also hard for the monks to get donations because they were so far away.

Franciscans usually built their convents inside or very close to cities. This was important because they were preachers and beggars, meaning they needed to be in constant contact with people to get support.

Some years later, Queen Violante, wife of Alfonso X the Wise, offered them a new plot of land and some houses. This new spot was much closer to the city's first wall. She officially gave them the land on March 6, 1267, in Seville. She wrote that she was giving the land:

... for the good and health and honor of the King and of my family and of my company.

The new site was large and located just outside the city walls. It was right next to the big market area. Over time, this entire space became the very center of Valladolid.

At first, the monks faced problems with the move. The abbot, Prince Sancho, and the Cathedral chapter were against it. But Queen Violant's strong support made the new location possible for the Franciscans. A century later, another queen, María de Molina, also helped the convent. She donated some palace-houses next to the convent, which helped it grow even bigger.

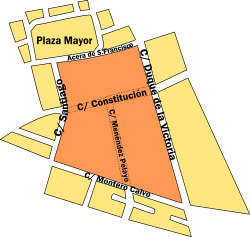

How the Convent Grew

The convent eventually covered a huge area. It stretched along the entire front facing the market square (which became the Plaza Mayor). It also turned the corner onto Olleros Street and went south to Verdugo Street. After a big change, Verdugo Street was renamed Montero Calvo Street. The convent continued along this street to Santiago Street and then went north back to the Plaza Mayor side.

This massive area included all the monastic buildings: the church, several cloisters (courtyards), a guesthouse, an orchard, animal pens, and gardens. There were also private houses that the Franciscans had sold or given away. A hospital called Juan Hurtado's Hospital and some city council offices were also nearby. These offices were used while the old City Hall building was being built.

The entire convent was surrounded by a fence, which was common for convents. It had two main entrances. One was the main door from the Plaza Mayor. This led to a large courtyard and then directly to the church. The church stood where Constitución Street is today. The other entrance was on Santiago Street, near the Iglesia de Santiago church. This was called Puerta de las Carretas (Carriage Gate). In 1599, a new doorway was built here with an arch and a statue of St. Francis. After passing through this door, a narrow alley led to the church.

The Convent's Life Until It Was Demolished

The Franciscans of this convent had a big spiritual impact on Valladolid's social life. It was also a center of culture and had a very rich history of religious events. Its complete disappearance in 1836 was a great loss for the city. However, getting back such a large piece of land led to important changes in Valladolid. The city was growing in that area and needed new buildings and roads.

In the early 1400s, the Franciscan monks had become a bit less strict. In 1416, a reform movement began, and several convents joined together. The Valladolid convent became the main center for the Franciscan Province of the Immaculate Conception. By then, this convent had a very large community. Father Sobremonte even wrote that:

... there were so many that they could not fit in the choir.

Many important events, both religious and related to the city's daily life, happened at the convent:

- In 1570, Friar Juan Perez de Pineda, a learned preacher and writer, moved to the Valladolid convent. He had faced some difficulties with the Inquisition.

- Juan de Zumárraga, the first bishop of New Spain (Mexico), was appointed in 1528. He had to return to Spain to be officially made a bishop. This ceremony took place in the convent on April 27, 1533.

- In 1695, a special ceremony was held for Francisco Juániz de Muruzábal y Ocáriz. He was the president of the Chancillería (a high court) of Valladolid and was appointed archbishop of Cartagena. A large procession entered the church. After the religious ceremony, there were celebrations with fireworks, drinks, and sweets.

- In 1740, a major meeting of the Franciscan Order was held at the convent. On June 5, the day of Pentecost, there was a huge procession. Many saints' statues were carried, and the procession ended with the image of the Immaculate Conception. This event was widely celebrated in the city.

- In 1746 and 1747, big celebrations took place for the official recognition of St. Peter de Regalado, who is the patron saint of Valladolid. On June 20, 1747, a statue of this saint was moved from the convent to the cathedral. Ventura Pérez described this event in detail, mentioning soldiers, music, and beautiful lights.

The convent's life continued smoothly until the Spanish War of Independence (early 1800s). During this time, many religious houses were closed down. On August 18, 1809, the convent got special permission to keep its church open. In September of that year, an inventory was made of all the valuable artworks.

Historian Ortega Rubio noted that in February 1811, the main doors, front, and courtyard of the church were torn down. Work began to build houses there. In February 1814, after the war with Napoleon, the Franciscans returned. They found their convent much smaller, as parts had already been sold. Then, in 1835, due to a process called confiscation, the orchard was also put up for sale. This orchard had fruit trees, elm trees, and a working waterwheel.

On August 6, 1836, the Official Bulletin of Valladolid announced the sale of the convent building. It included the church, chapels, rooms, cellar, courtyards, orchard, wells, stables, and barns. It was valued at a very high price. Since no one bought it, the government decided to demolish it at the State's expense.

The demolition started on February 1, 1837. Once all the buildings were gone, the plots of land were sold. Buyers had to give a part of the land to the City Hall to open a new street, which would become Constitución Street. Many of the convent's old tiles were used to pave the old City Hall and build its clock tower. The demolition work continued for almost a year. Some important artworks were saved by the State and moved to the National Sculpture Museum. However, most of the art disappeared without a trace because no records were kept.

The Convent Grounds from the 19th to 21st Century

Finally, in 1847, a businessman named Pedro Ochotorena bought all the land from the City Council. He promised to open the required street, Constitución Street. He then opened another street, Mendizábal, which was perpendicular to Constitución. This new street was named after the minister who had promoted the sale of church lands. Years later, Mendizábal Street was renamed Menéndez Pelayo.

Slowly, from the late 1800s to the early 1900s, new buildings and private homes were built on the former convent grounds. In 1853, the Casino Cultural Society bought land and built a building that was later rebuilt in 1901. In the late 19th century, Antonio Ortiz Vega built a large palace with a big garden. This palace later became the headquarters of the Banco Castellano in 1900.

In 1884, the Zorrilla Theater was built. Its main entrance was on Constitución Street, so it would fit in with the arcades of the Plaza Mayor. In 1928, the Telefónica building was built on Duque de la Victoria Street. In 1934, the La Unión and Fénix buildings were constructed at the corner of Constitución and Santiago streets.

The Hotel Europa (now gone) was built on Constitución Street, across from the Zorrilla Theater. When this hotel was torn down in the 1970s to build the Galerías Preciados department store, workers found several burial sites and remains of columns and foundations from the old convent.

Fires at the Convent

A large fire in Valladolid on September 21, 1561, also damaged the convent, especially its front. After this disaster, the city began major rebuilding and redesigning, which included building the final Plaza Mayor. For the area in front of the convent, King Philip II issued a special order on December 23, 1564. It said:

That the doorway of Sant Francisco be built, bringing it up to the level of the others and above it a corridor with an altar to say mass and above this corridor, there should be others up to the height of the houses on one side and on the other, so that the texearoz is all one.

On June 1, 1699, a smaller fire started in the neighboring houses and spread to the convent.

Guilds and Brotherhoods

The convent had strong ties to two important brotherhoods: the Vera Cruz and the Passion. The Cofradía de la Vera Cruz actually started within the convent. Even after it got its own building in the late 1500s, the Franciscans continued to support it, and they always had a good relationship.

The Cofradía de la Pasión had a special role. They were in charge of finding the bodies of executed people and bringing them to the Convent of St. Francis. On Lazarus Sunday (the fifth Sunday of Lent), they would accompany the bodies to a special chapel in the convent. This chapel served as a place for their burial and was called the Capilla de los Ajusticiados (Chapel of the Executed).

In the chapel of St. Anthony of Padua, the tailors' brotherhood had their special place from the 17th century onwards. The chapel of the Counts of Cabra was supported by the Cofradía de Nuestra Señora de la pura y limpia Concepción (Brotherhood of Our Lady of the Pure and Clean Conception).

- Fronts of the two churches that were the headquarters of the brotherhoods

Architecture and Works of Art

Front Facing the Plaza Mayor

We know what the convent's front, facing the Plaza Mayor, looked like from drawings by Ventura Pérez (18th century) and paintings from 1506 and 1656. Sobremonte wrote that between 1455 and 1456, the front was changed. A second floor with a balcony was added. This balcony had an altar, so merchants could hear mass without leaving their work.

After the fire of 1561 and King Philip II's order, the front was restored. The balcony for mass was kept, and the front was made to match the height of the houses next to it. In 1727, a statue of St. Francis was placed on the front. This caused a disagreement between the monks and the City Council, who were upset that the convent had changed its front without permission.

The Church

There are no drawings or paintings of the church building itself. However, we can learn a lot about it from old documents in archives and descriptions by historians and travelers. These sources describe its layout, interior, chapels, and artworks. An inventory from 1809, made during the French occupation, is very valuable. It listed 8 bronze or gilded lamps, 16 confessionals, and 22 altars, among many other items.

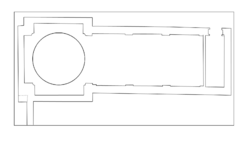

The church's main door was originally at the west end. Later, it was moved to the north side, between the chapels of Santa Catalina and San Antonio de los Cañedos. This door had a vaulted stone entrance area. The church was built in the Gothic style and had one main aisle, about 39.20 meters long and 12.60 meters wide.

At first, only the main chapel had a vaulted ceiling, while the rest of the church had a wooden roof. But in the 1500s, changes were made, and seven ribbed vaults were added. The church had 10 chapels in addition to the main one. All these chapels were built and supported by the city's most important families. These families also used the chapels as burial places. Even royal people were buried under the church's vaults.

Main Chapel

Since the convent was originally supported by royalty (three queens: Berenguela, Violante, and María de Molina), the main chapel was also a royal foundation. Over the centuries, this support passed to other important people, like nobles or wealthy merchants.

In the early 1500s, the Gómez Manrique de Mendoza family wanted to take over the chapel's patronage. The monks strongly opposed this. Still, in 1613, Carlos Manrique de Mendoza, Count of Castro, buried his parents' remains in this chapel. He had brought them from Castrogeriz in Burgos. It seems they either didn't get full control or shared it with a merchant named Alonso de Portillo. In 1543, Portillo hired plasterers to decorate the chapel.

The main chapel was entered through a pointed arch and separated from the rest of the church by a screen. Inside this area were the Rivera family's chapel, the Old and New sacristies (rooms for church items), and the San Bernardino chapel. The main chapel had valuable artworks and paintings, listed in the 1809 inventory. Besides the main altar, it had two side altars.

Altarpieces

The main chapel had three different main altarpieces over time, and two side altarpieces that were also replaced.

The first main altarpiece was bought in 1578, as wished by Gómez Manrique, son of the Counts of Castro. Martí y Monsó studied this in great detail, using documents about its value and buyers.

A second altarpiece with paintings was installed around 1622. It didn't last long, as it was taken apart and sold by 1674. It was sold for 5000 reales to the parish church of Laguna de Duero (Valladolid). There, it was put back together by Blas Martínez de Obregón. It has a base, two main sections, three vertical parts, and a top section. The first section has statues of St. Anthony of Padua and St. Bernardino of Siena. The second section has San Buenaventura and a bishop. These four paintings are by Diego Valentín Díaz. The two central paintings show the Assumption of Mary and the Coronation, by Diego Díez Ferreras. The top section has a painting of God the Father and Jesus Christ.

The third altarpiece was paid for by the Mendoza family in 1674. Documents show that in 1674, Miguel Jeronimo de Mondragon agreed to gild this altarpiece. This altarpiece was seen by historian Canesi and was a highlight in the 1809 inventory.

Grilles

The main chapel had two grilles (decorative screens) that separated the altar area from the rest of the church. Not much is known about the first one, except that it was not very impressive. So, the monks ordered a second one from Biscay, which was not finished. The finishing work was given to Rodríguez de San Pedro. Canesi and Martí y Monsó believe that Friar Pedro Villate, a lay craftsman, helped finish this grille.

1809 Inventory

On the north wall, there were three paintings with gilded frames. They showed St. Joseph, St. Dominic, and St. Francis. On the front wall, there were three more. One of them was well described by the traveler Ponz in his Viage a España: "Our Lady standing with St. Francis kneeling before her," by the painter Mateo Cerezo. This painting is now in the Lázaro Galdiano museum in Madrid.

Chapel of the Rivera Family

This chapel was also known as the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception. Its founder was Andrés de Rivera, a lord and mayor of Burgos. In his will from 1518, he clearly explained how the chapel should be built and where he wanted to be buried. This chapel was to be built next to the main chapel of the convent church.

[...] that the said my chapel should go out to the main chapel of the said monastery [...].

It was dedicated to Nuestra Señora de los Remedios (Our Lady of Remedies). Andrés de Rivera gave very detailed instructions, even about the altarpiece. A century later, the chapel was in poor condition. The monks had to ask the founder's descendants for money to maintain it.

By 1628, the chapel had an altarpiece with a statue of the Immaculate Conception, made by the sculptor Francisco de Rincón. For many years after, the chapel was neglected. Then, in 1675, it was completely changed. Its name and dedication were changed, and it became the chapel of Our Lady of Copacabana.

Chapel of Our Lady of Copacabana

This chapel took over the same space as the Rivera family chapel, but with a new name and dedication. Between 1676 and 1679, it was expanded and repaired, becoming a significant part of the convent. In 1679, the work was finished, and a ceremony was held to bless the statue of the Virgin of Copacabana and place her in her chapel.

The chapel was supported by Friar Hernando de la Rua, a monk from the convent. He had been a General Commissioner in New Spain (America). Friar Hernando brought the statue of Copacabana from America, where it was greatly loved. The master builder Juan Mazo carried out the construction work, using stone from the Valladolid town of Campaspero. Antonio de Bustamante directed the project. The chapel turned out to be quite large, almost like a small church itself. It had a main chapel, a cross-shaped area, a main altar, two side altars, two more altars in the nave, a sacristy, and a choir with a small organ. The outside was topped with a spire.

Altarpiece

The historian Canesi described the altarpiece, which was put together by Blas Martínez de Obregón. It had a base with pillars and twisted columns. The Virgin of Copacabana was placed in the main section. Below her was a tile painting with the coat of arms of Ana Mónica Pimentel y Córdoba, who was the first lady-in-waiting to the Virgin.

Doors

The main door leading to the main chapel was rebuilt. Four smaller doors were also opened, leading to the church and the sacristy. This work was done by Obregón.

1809 Inventory

The inventory listed five altars with their items, a chest with seven vestments for the Virgin, and a chest with three Franciscan robes. It also mentioned a book with silver covers of St. Peter de Regalado and several paintings on the walls. In the room next to the chapel, used by the sacristan, there was a cupboard, gilded sheets, a canopy, seven straw chairs, a bed, two small trunks, and a chest.

Chapel of St. Anthony of Padua

This chapel was on the north wall of the church. It was founded in the 15th century by Luis Morales, a treasurer for King John II of Castile, and was dedicated to Santa Ana. Later, it was owned by the Ulloa family. In the 17th century, another member of that family sold the chapel to the Brotherhood of the Mancebos Sastres (Young Tailors). From then on, it was called the chapel of San Antonio de Padua, who is the patron saint of this brotherhood.

In 1650, the Brotherhood ordered an altarpiece from José de Castilla. The contract stated that the master would be paid 5900 reales. In the center was a statue of St. Anthony that had been brought from Florence by a banker named Jácome Espínola. Sobremonte described this statue as "very good" and said it was known as San Antonio el Rico (St. Anthony the Rich) to tell it apart from another chapel called St. Anthony the Poor.

Chapel of St. Francis

This chapel was previously called the chapel of St. Mancio. It was founded by Ruy Pérez de Agraz, a crossbowman. Later, its patronage passed to the Hospital de Esgueva.

Chapels of St. Catherine and St. Charles Borromeo

These two chapels were next to the chapel of St. Francis, on the north wall of the church. Carlos de Venero y Leyva, a chaplain to King Philip III, gained control of these chapels. Documents from 1602 and 1603 about this are kept in the Provincial Historical Archive of Valladolid. The chapel of Santa Catalina must have been very large and, according to Sobremonte, it was:

[...] the most modern and the most elegant, majestic and neatest of the church.... [...]

The archive documents also mention masses and memorials for the founder and his family. They also detail the work done to improve and decorate the chapel, all paid for by Carlos de Venero. He spent a lot of money on the works and on church items. An altarpiece of St. Catherine, mentioned by Sobremonte, cost 600 ducats. The chapel of St. Charles Borromeo had no direct entrance from the church. It was like an extra room connected to the St. Catherine chapel, bought and rebuilt by the same sponsor in 1624.

Tombs and Other Artworks

Some of Valladolid's most famous families were buried in this chapel, which is why it was sometimes called the chapel of the Lineages (families). These included the Mudarra, Ondergardo, Zárate, Venero, and Leyva families. The burial statues of the Leyva family were made by followers of the sculptor Pompeo Leoni. They were listed in 1861 and moved to the cathedral.

There, you can also see the altarpiece and a statue of St. Catherine made by Francisco de Rincón, along with other smaller statues.

Chapel of St. Anthony the Poor

This chapel was at the foot of the church, below the choir. It included the space of two earlier chapels called the Chapels of the Trinity and St. Anthony. It was remodeled and decorated in 1617. It was also known as the chapel of the Cañedos family, whose burials were in two plaster tombs under Gothic arches.

Chapel of St. Anne

After 1659, this chapel was owned by three different families. First, it was bought by Casilda de Espinosa. Then, it passed to Juan de Para, an accountant. Finally, it was inherited by Sebastián Montero de Espinosa and Juana Durango de Quirós. The chapel had two grilles, one facing the church's main aisle and the other facing the nave de Santa Juana.

Chapel of St. Diego

This chapel, like the ones below, was on the south wall of the church and had access to the cloister. Its supporter was Diego de Escudero. It had a statue of its patron saint, Didacus of Alcalá, made by Gregorio Fernández.

Chapel of the Incarnation

There were two chapels with this name. This one was previously called the chapel of Santiago. In the 17th century, it was supported by Clemente Formento, a city council member, who bought it in 1622. He undertook restoration work and changed its dedication. His family's coat of arms decorated the chapel. Descriptions of this chapel are found in several documents, allowing for a good understanding of its parts and the artists who worked on it. The new designs were by Francisco de Praves and Rodrigo de la Cantera. The entrance arch was made of stone. The master builders were Pedro de Vega and Domingo del Rey. The altar was on the east wall, and a door on the back wall led to the cloister.

Grille

The chapel was enclosed by a grille made by Matías Ruiz, based on a wooden model. It had 32 balusters (small columns) and sat on a stone base. The top part was made of wood.

Altarpiece

It had one main section and a top part, with a large painting of the Annunciation, believed to be by Diego Valentín Díaz. The altarpiece was gilded by Tomás de Prado, who also gilded the grille, according to archive documents.

Chapel of Our Lady of Solitude

The first person to support this chapel was Pablo de la Vega. His portrait hung on one of the walls with a caption that read:

D. Paulus de la Vega Huius saceli primus patronus

In 1590, Juan de Sevilla and his wife Ana de la Vega inherited the chapel. At that time, it was dedicated to San Bernardino. In the 17th century, it belonged to Francisco de Cárdenas, who ordered an altarpiece dedicated to the Pietà (a depiction of Mary mourning Jesus), changing the chapel's dedication.

Altarpiece

The altarpiece and the sculpture group of the Pietà were made by Gregorio Fernández. After the convent was closed, they were moved to the church of San Martín de Valladolid, to a chapel owned by the Fresno de Galdo family.

Chapel of the Holy Christ

This chapel was on the south wall of the church, facing the cloister. In 1576, it was named after St. Andrew. The monks sold it to their family doctor, Juan Rodríguez de Santamaría, to be used as a burial chapel for him and his family. Juan Rodríguez restored and decorated it.

Inventory

According to Sobremonte, this chapel had a plain wooden altarpiece with small figures showing the Passion and death of Christ. This altarpiece has been identified with one now in the National Sculpture Museum. It is a Flemish triptych (three-paneled artwork) made of unpainted walnut. Rafael de Floranes mentioned a large Christ statue in the "altarpiece of the Crucifix," which gave its name to this chapel at one point. Its current location is unknown.

Chapel of the Incarnation (Second)

This was the second chapel with this name. It was located below the choir and was previously dedicated to San Pablo. In the 16th century, its patrons were Antonio de Frómista and his wife Juana de la Vega.

Choir

Until the 16th century, the church's choir (where the monks sat) was in the presbytery (the area around the altar). Then, the convent decided to move it and build a new one at the back of the church, on an upper level. This new choir had two rows of seats, totaling 84. At times, the convent had over 100 monks, so not all could sit.

The old choir was made by two Franciscan carvers. The new choir, in the rococo style, was made in 1735. The carving was done by Pedro de Sierra, and his brother Friar Jacinto de Sierra assembled it with the help of other craftsmen. Ventura Pérez, who was also an assembler, wrote about it in his Diario de Valladolid:

Year of 1735, day of St. Francis the choir stalls of the choir of his royal convent were premiered, although not completely perfected, that of all point was concluded on December 7 of said year. Juan de Soto, general minister of the whole order and son of this city and convent. Jacinto de Sierra, religious Recollect priest of the above mentioned order, son of the convent of the Abrojo; and of the officers who completed it, among the many who worked on it, were Tomás Rey, Manuel Villa, Manuel Mazariegos, Juan de Paredes, Manuel Conde, José García and myself, Ventura Pérez. May it be to the honor and glory of God and his divine worship.

News from Historians About the Choir

According to Canesi, the choir's floor was made of brick and tiles. It was paid for by the Great Captain, a famous military leader who had stayed at the convent. In 1567, María de Mendoza donated money for the monks to repair the collapsed vaults.

Sobremonte, in the 17th century, mentioned another work: securing the choir with two pillars. This is supported by the will of the master builder Pedro de Vega, who stated that the convent "owed him money for the work done on the supporting pillars of the choir."

García Chico, in his work Documentos.... Pintores II (Valladolid 1956), says that in 1612, Diego Valentín Díaz painted a canvas to be placed between the two doors of the choir.

In 1740, according to Ventura Pérez, the statue of the Immaculate Conception, made by Pedro de Sierra, was still in the choir.

1809 Inventory

The choir had an altar called the altar of the Most Holy Christ of the Chapter. It also had two organs, one larger than the other, and a lectern (a stand for reading) decorated with the Ecce Homo. There was an urn where St. Francis de la Parrilla was honored. The statue of the Inmaculada and some panels from the 1735 choir stalls are now kept in the Sculpture Museum. A large part of the seats were moved and set up in the choir loft of the chapel of the Colegio de San Gregorio (which is now part of the National Museum of Sculpture).

Royal Burials

- The infant Peter of Castile, son of Alfonso X the Wise and his wife, Violant of Aragon. He died in Ledesma on October 20, 1283. According to Antolínez de Burgos, his remains were in a niche on the right side of the main chapel. However, Ambrosio de Morales said the tomb was in the Chapel of the Lions, high up, with statues of the infant Peter and his wife.

- Henry of Castile "the Senator", son of Ferdinand III the Saint and brother of Alfonso X the Wise. He died in August 1303 in Roa, Burgos, and his body was brought to the convent. In the 16th century, the chronicler Ambrosio de Morales noted that the exact burial place of Prince Henry was unknown. However, Antolínez de Burgos stated that his remains were in a niche on the left side of the main chapel.

Burials of Other Important People

- Pedro Álvarez, lord of Noreña, father of Rodrigo Álvarez de las Asturias. On his tomb, there were some Latin verses that have been passed down in a manuscript history of the convent:

Serve Dei Francisce, mei sis dux morientis;

Do tibi me, tu sis animae comes egredientis.

In te confido placuitque mihi tuus ordo.

This translates to:

Servant of God, Francis, be my guide in death;

For that to thee I give myself, accompany my soul

when I leave the world. In thee I trust,

and in the prudence of your rule I glory".

- Álvaro de Luna, a powerful nobleman, was executed in the Plaza Mayor of Valladolid. He was buried in this convent, as he wished. Later, his remains were moved to the Toledo Cathedral (Santiago chapel), along with his wife's and other family members.

- Christopher Columbus, whose remains were also moved several times.

- María de Mendoza, VII Countess of Rivadavia.

- Red Hugh O'Donnell (Aodh Rua Ó Domhnaill), the last prince of Tyrconnel (Ireland). He died during a trip to Valladolid and was temporarily buried in Simancas Castle in 1602. Later, he was moved to the convent.

- Friar Alonso de Burgos (bishop of Palencia and founder of the Colegio de San Gregorio).

- Juan Hurtado de Mendoza (14th century), one of the guardians of King Henry III.

This was a long section built at the foot of the church, as wide as the church itself, and running perpendicular to the main aisle. It was like a real church, with a main altar and eight chapels on both sides. The chapels on the right side were: San Diego, San Miguel, Santa Ana, and Santo Cristo. The chapels on the left side were: San Cosme and San Damián, Nuestra Señora la Blanca, San Juan Bautista, and Nuestra Señora. You could enter it from the cloister, and it served as a walkway to reach the main entrance, which faced the Plaza Mayor.

Chapel of the Executed or Chapel of the Holy Passion

This chapel was next to the nave of Santa Juana, in the first courtyard you entered through the main door. It was built in 1598. According to Sobremonte, it was located:

[...] between the door of the church or nave of Santa Juana and the wall of the house of Baltasar de Paredes [...].

It had an altar with a statue of Christ, accompanied by the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist. A candle was always lit there. On the floor, there were large burial slabs for executed people. On the chapel walls, an inscription explained that the Royal Penitential Brotherhood of Our Lady of the Passion and Saint John the Baptist beheaded supported it. It also mentioned special blessings given by the bishop of Valladolid, Juan Vigil de Quiñones, for those who prayed in the chapel for the souls of the buried.

This chapel worked this way for two centuries. In the early 1700s, the building was remodeled at the request of Antonio Fernández and other religious people who donated money for the work. The new construction was done by the master builder Joseph Gómez, who even donated his fee for the project.

Ventura Pérez wrote in his Diario de Valladolid in 1752 about the building of a new chapel next to the old one. This new chapel was for the burial of nobles and those executed by garrote (a method of execution).

Sacristy and Resacristy

The sacristy was a rectangular room, about 16.80 meters long and 7.28 meters wide. It was built around 1574 and extended along Olleros Street, where three windows opened. On the opposite side, it was attached to the main chapel and the chapel called the Chapel of the Lions. It had a ribbed vault ceiling and was strengthened with buttresses. Next to it was a small washing area, also with a ribbed vault. A little further, behind the church's altar area, was the chapel of San Bernardino, which served as a resacristy (a smaller sacristy).

1809 Inventory

The list of movable and valuable items in this room was very long. Among many other things, it described:

- Walnut drawers and a table.

- Five full-length mirrors with decorated frames.

- Nine paintings with gilded frames, showing San Buenaventura, San Pedro Regalado, the Descent from the Cross, the Immaculate Conception, the Scourging of Christ, San Joaquín, Pope Innocent XI, Pope Clement XIV, and Cardinal Cánsate. It said "all with their gilded frames." There were also nine or more smaller paintings on different subjects and portraits.

- A Holy Christ statue made of ivory, now in the National Sculpture Museum (Valladolid).

- A reliquary (a container for holy relics).

- A gilded chest with crystals.

- A display case with a clock and various silver pieces, plus church ornaments (10 chalices, a silver lamp, a tabernacle covered in silver, carpets, etc.).

Main Cloister

The monastery had other cloisters or courtyards besides the main one, but their exact locations and uses are not well known. The main cloister was next to the south wall of the church. It was built in the late 15th century and rebuilt by Diego de Praves in 1595. In the 17th century, it was decorated with a tiled base and its floor had geometric patterns. It had paintings on the walls showing the life of St. Francis, made by Felipe Gil de Mena. This painter worked a lot in this cloister, creating large paintings and also painting the curved parts of the vaults. Another painter was Friar Diego de Frutos, a lay brother of the convent, who painted the life of St. Pedro Regalado in the 18th century. In 1641, the painter Blas de Cervera painted the lower cloister with stories from the life of St. Francis.

Chapel of Santa Cruz

Also called the chapel of the Santisteban family, one of Valladolid's notable families. Historians believe this chapel was next to that of the Counts of Cabra. Old convent books say it served as the first church for the monks before the main church was built.

Chapel of the Porziuncola

According to Sobremonte, this chapel was on the second side of the cloister. It belonged to the Vitoria family, with the treasurer Luis de Vitoria as its patron. He spent a lot of money fixing it up, adding a grille, an altarpiece from 1622, and decorations, including their family coats of arms on the walls. The chapel had two good railings, one separating it from the church and the other from the cloister. When Luis de Vitoria died, his daughter Antonia de Vitoria inherited the chapel.

Chapel of the Counts of Cabra

This chapel had several names over the years:

- Chapel of St. Anthony

- Chapel of the Conception

- Chapel of Las Maravillas

- Chapel of the Counts of Cabra

- Chapel of the Conception (and also of the Reliquary and the Communion rail).

It was located near the cloister. According to historian Canesi, it was "in the dark passageway on the right hand side of the main chapel."

Patronage

In the early 16th century, Luis de la Cerda and his wife Francisca de Castañeda were the patrons of the chapel. Their granddaughter, Francisca de la Cerda Zúñiga y Castañeda, married the III Count of Cabra, Diego Fernández de Córdoba. This couple again became the patrons, and from then on, the chapel was named after the Counts of Cabra.

In 1617, the patronage went back to the convent. This was when the famous Immaculate Conception statue by Gregorio Fernández was placed in this chapel. It was the first in a series of Immaculate Conception statues made by this sculptor. Its current location is unknown, making it a mystery for art historians. In the 18th century, the monks gave the patronage to Lope de Quevedo, to whom they owed many favors.

The Confraternity of the Conception

The Confraternity of Our Lady of the Pure and Clean Conception had its main meeting place in the convent. They held their religious festivals, meetings, and chapters there. In 1617, the monks gave this brotherhood the chapel of the Counts of Cabra, which was again called de la Concepción. This allowed them to hold all their events there. For this occasion, the monks provided a statue of the Immaculate Conception that they had ordered from the sculptor Gregorio Fernandez, who was a member of the brotherhood. The community also offered a silver lamp.

However, the monks were very clear in the contract that they would always own this sculpture and other items they mentioned:

[...] because everything that is given and acquired after the foundation of the said confraternity is given and offered to the image of Our Lady and not to the confraternity [...] excluding what the confraternity and confreres have put of their property [...].

The contract also stated that the feasts of the Immaculate Conception and the Feast of the Dead were to be celebrated in the chapel. The monks also offered another room for meetings, which was next to the main balcony overlooking the square. In return, the brotherhood agreed to pay an annual donation of 200 reales and promised to bury all the monks of the convent. Later, there was a new agreement where the brotherhood said they were happy to meet in "the room where theology is read [...] where up to now the chapter meetings have been held and are held [...]." In exchange, they no longer had to bury the monks.

The Statue of the Immaculate Conception

We know that in November 1617, Gregorio Fernández had finished this statue. It was the first of many Immaculate Conception statues he would make throughout his life. In 1618, the Brotherhood of the Conception ordered an altarpiece to display it. The convent then hired the famous painter Tomás de Prado to gild it on June 16, 1619.

In 1622, the convent ordered a new altarpiece for its main chapel. They moved Gregorio Fernández's Immaculate Conception statue to the central spot there. In its place, in the chapel of the Counts of Cabra, they put another Immaculate Conception statue, made by Francisco de Rincón.

In the 1809 inventory, this statue by Gregorio Fernández is described:

[...] the throne of the Immaculate Conception, with its image that has its bronze crown, with its arches with silver rays, some gilded and in the arches several embedded stones. Behind this throne there is a kind of dressing room [...].

As mentioned, this statue is now missing and is a big mystery among Spanish art historians.

Chapel of the Bishop of Mondoñedo

This chapel is also called the Chapel of the Sepulchre because it contains a famous sculpture by Juan de Juni. Many writers have provided information about this chapel, and there are several documents about contracts for building work and artists' agreements.

The chapel was built at the request of Friar Antonio de Guevara (a Franciscan who died in 1545). He was a bishop, writer, and historian for Charles V. He wanted it as a burial chapel. It was built "in the dark passage between the cloister and the sacristy," near the chapel of the Count of Cabra. A small cloister was also built in front of it. Friar Antonio de Guevara also paid for two other cloisters. One contract mentions the carpenter Pedro de Salamanca, who was asked to:

[...] to make 4 cloisters, which are the 3 cloisters and for the room towards the refectory I have to make a cut in the wall of the refectory so that it fits the height of the sill [...] and more I have to make a vestibule [...].

The chapel was designed by the sculptor Juan de Juni. It had a square shape with a main wall where an altarpiece would hold his great work, The Burial of Christ. This sculpture is now in the National Sculpture Museum. The altarpiece and the entire chapel were decorated with plasterwork by Jerónimo del Corral.

In 1686, the chapel must have been showing its age. The gilder Manuel Martínez de Estrada was hired to clean and restore the gilding and paintings, fixing any damage. This restoration contract details all the elements, so we know the chapel was decorated with fancy designs, flowers, masks, shells, garlands, angels, and other sculptures.

1809 Inventory

The inventory mainly mentions the sculpture The Burial of Christ by Juan de Juni, and paintings of the apostles on the walls.

Chapel of the Venerable Third Order

From 1609 onwards, the convent became the center for the spiritual life of the Third Order (V.O.T.). This group was made up of men and women from different social backgrounds. All their social and religious events took place at the convent. Until 1620, this brotherhood met in various chapels within the convent. Then, the monks sold them some land near the nave of Santa Juana and a large room that had been a guesthouse.

In this area, the chapel and other rooms were built around 1622. The master builders were Domingo del Rey and Antonio de Morales, and the design was by the architect Francisco de Praves. The expansion continued in 1626 when they got a little more space next to the chapel for a sacristy, in exchange for donations. In 1654, there was another expansion led by architect Juan de Répide, and the church was rebuilt with this inscription:

To the honor and glory of God and the Blessed Virgin Mary N. S. conceived without original sin, and N. P. S. Francisco, this Chapel was rebuilt and adorned, with the alms that the brothers of the Third Order of Penance gave for it, being minister of it, the brother Andrés García, year of 1655.

After the expansion, it became a real church, 25.20 meters long and 7.84 meters wide in the nave, plus 9.80 meters wide in the main chapel. The sacristy was on the left side of the altar. The church's main body was divided into 3 sections, and the roof was vaulted and made of brick. The floor was also brick, and the walls were whitewashed.

In 1675, the painter Antonio de Noboa Osorio covered the walls with paintings. He also gilded and decorated many other parts of the church, like the vaults, arches, and windows. A few years earlier, Diego Valentín Díaz had painted the curved triangular sections supporting the dome. Sobremonte and Father Calderón described the result of all these works, giving the impression of a beautiful Baroque design rich in themes and colors. They also described the furniture and different areas: two side altars, a choir with an organ, a sacristy with rich ornaments, a pulpit, and a small garden.

The first main altarpiece (which burned in 1710) was, according to Sobremonte, "all of it an ember of gold." It was made by Antonio Villota, with twisted columns, and was divided into two main sections and three vertical parts. A statue of the Immaculate Conception was placed in the central section. The second altarpiece was made by the gilders Claudio and Cristóbal Martínez de Estrada.

The Convent in the 21st Century

Today, nothing remains of the huge Convent of St. Francis in the memory of Valladolid's citizens. The new streets built on its site don't remind passersby of what stood there centuries ago. Only the name Acera de San Francisco (Sidewalk of St. Francis) remains as a memory. This name is used by older people to refer to the arcades of the Plaza Mayor, though it's not official. The Franciscans have lived at Paseo de Zorrilla nº 27 since the mid-20th century. There, they have the church-parish of the Immaculate Conception, a modern building designed by the Valladolid architect Julio González Martín.

See also

In Spanish: Convento de San Francisco (Valladolid) para niños

In Spanish: Convento de San Francisco (Valladolid) para niños

- Franciscans

- Order of Friars Minor Conventual

Images for kids

-

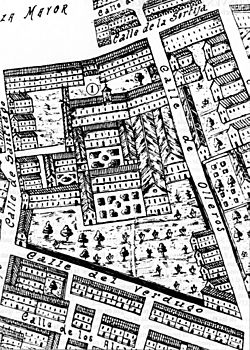

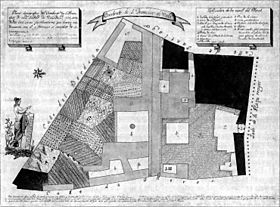

Plan by Rodrigo Exea (1835), copying Francisco Benavides' original of 1810. Preserved in the Valladolid Museum.

1.- Entrance to the church and convent.

2.- Atrium of the church.

3.- All that comprises the temple, chapels, cloister, sacristy and offices related to it.

4.- Courtyards of lights.

5.- Corral of the door of the houses.

6.- Orchard.

7.- Snow well.

8.- Private houses.

9.- Gateway of the Santiago Street.

10.- Cistern.

11.- The loose shade color includes in all the planthe other offices of the servitude of the convent. -

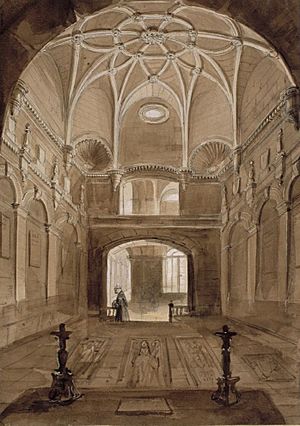

Nineteenth century engraving representing the chapel of Santa Catalina known as the Linajes, by Valentín Carderera.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |