Early American currency facts for kids

Early American currency is all about the money used in the United States when it was first being settled and after it became its own country. Back in 1652, the Massachusetts government allowed a person named John Hull to make the first coins for the colony. These coins included the willow, oak, and the pine tree shilling.

Because not many coins were made in the Thirteen Colonies, people often used money from other countries. For example, the Spanish dollar was very common. Sometimes, the colonial governments printed their own paper money to help people buy and sell things. However, the British Parliament, which was the government in Great Britain, passed laws in 1751, 1764, and 1773 to control this paper money.

During the American Revolutionary War, the colonies became independent states. They no longer had to follow British rules about money. So, each state started printing its own paper money to pay for the war. The Continental Congress, which was the government for all the colonies fighting for independence, also printed paper money called continental currency to fund the war.

Printing too much of this paper money, especially during the war, caused prices to go up very quickly. This is called inflation. People even had a saying, "not worth a continental," because the money lost its value so fast. By the end of the war, this paper money was almost worthless. British groups also made fake money, which made the problem even worse. This experience showed how risky it was to print money without enough control. Because of this, the United States later decided to use a system where money was based on both gold and silver, starting with the Coinage Act of 1792. This helped create a more stable money system.

Contents

Money in the Colonies

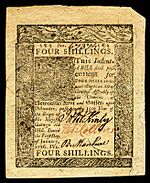

In the British colonies of America, people used three main types of money. These were specie (which means coins), printed paper money, and commodity money. Commodity money meant using valuable goods like tobacco, beaver furs, or wampum (beads made from shells) as payment. People used commodity money when there weren't enough coins or paper money around.

The cash in the colonies was measured in pounds, shillings, and pence. However, the value of these amounts was different in each colony. For example, a pound in Massachusetts was not worth the same as a pound in Pennsylvania. All colonial pounds were worth less than the British pound sterling. Most of the coins used in the 1600s and 1700s came from Spain and Portugal. The Spanish dollar was widely accepted for a long time. This is why the United States later decided to use dollars instead of pounds for its money.

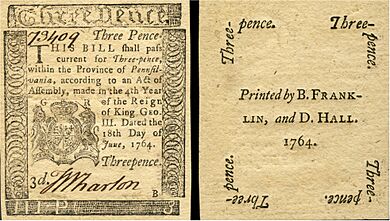

Over time, colonies started printing their own paper money. This made it easier to trade and buy things. On December 10, 1690, the Province of Massachusetts Bay was the first government in the Western world to print its own paper money. They did this to pay for a military trip during King William's War. Other colonies soon followed, printing their own money during other conflicts.

The oldest surviving paper bill is from February 3, 1690. It was worth 20 Massachusetts shillings, which was equal to one pound.

However, when each colony printed its own money, problems started. Each colony's dollar had a different value, which made trading between colonies confusing. The British Parliament eventually tried to stop the colonies from printing paper money. This also made it easier for people to create fake money, which caused problems for everyone.

The paper bills printed by the colonies were called "bills of credit". These bills could not be immediately exchanged for a set amount of gold or silver coins. Instead, they were meant to be paid back at a future date. Colonial governments usually issued these bills to pay their debts. They would then take the money out of circulation by accepting the bills as tax payments. If governments printed too many bills or didn't collect them back through taxes, it led to inflation. This happened a lot in New England and the southern colonies, which were often at war. Pennsylvania, however, was careful not to print too much money. Their paper currency, which was backed by land, generally kept its value against gold from 1723 until the American Revolution began in 1775.

This drop in value of colonial money was bad for British lenders. Colonists would pay their debts with money that was worth less than before. To fix this, the British Parliament passed several laws called currency acts. The Currency Act 1751 limited how much paper money New England could print. It allowed old bills to be used for public debts (like taxes) but not for private debts (like paying merchants). In 1776, a Scottish economist named Adam Smith criticized these colonial bills in his famous book, The Wealth of Nations.

Another law, the Currency Act 1764, extended these limits to colonies south of New England. This law didn't stop them from printing paper money. But it did stop them from making their currency "legal tender" for any debts, public or private. This caused a lot of tension between the colonies and Britain. Many people believe this was one reason for the American Revolution. After a lot of discussion, Parliament changed the law in 1773. This allowed colonies to issue paper money as legal tender for public debts. Soon after, some colonies started printing paper money again. When the American Revolutionary War started in 1775, all the rebel colonies, which soon became independent states, printed paper money to pay for their military costs.

A Look at Colonial Currency from the 13 Colonies

The table below shows examples of colonial currency from the original Thirteen Colonies. These examples are from the National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution. They were chosen because of the important people who signed them. These signers were often involved in big events like the 1765 Stamp Act Congress or signed important documents like the United States Declaration of Independence.

| Colony | Value | Date | Issue | First | Note (obv) | Note (rev) | Signatures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

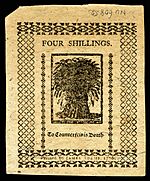

| Connecticut | 40s (£2) | 1775-01-02 | £15,000 | 1709 |  |

|

Elisha Williams, Thomas Seymour, Benjamin Payne |

| Delaware | 4s | 1776-01-01 | £30,000 | 1723 |  |

|

John McKinly, Thomas Collins, Boaz Manlove |

| Georgia | $40 | 1778-05-04 | £150,000 | 1735 |  |

|

Charles Kent, William Few, Thomas Netherclift, William O’Bryen, Nehemiah Wade |

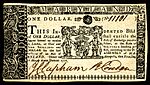

| Maryland | $1 | 1770-03-01 | $318,000 | 1733 |  |

|

John Clapham, Robert Couden |

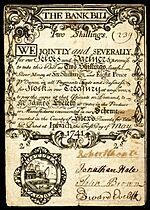

| Massachusetts | 2s | 1741-05-01 | £50,000 | 1690 |  |

|

Robert Choate, Jonathan Hale, John Brown, Edward Eveleth |

| New Hampshire | $1 | 1780-04-29 | $145,000 | 1709 |  |

|

James McClure, Ephraim Robinson, Joseph Pearson, John Taylor Gilman (rev) |

| New Jersey | 12s | 1776-03-25 | £100,000 | 1709 |  |

|

Robert Smith, John Hart, John Stevens Jr. |

| New York | 2s | 1775-08-02 | £2,500 | 1709 |  |

|

John Cruger Jr., William Waddell |

| North Carolina | £3 | 1729-11-27 | £40,000 | 1712 |  |

|

William Downing, John Lovick, Edward Moseley, Cullen Pollock, Thomas Swann |

| Pennsylvania | 20s (£1) | 1771-03-20 | £15,000 | 1723 |  |

|

Francis Hopkinson, Robert Strettell Jones, William Fisher |

| Rhode Island | $1 | 1780-07-02 | £39,000 | 1710 |  |

|

Caleb Harris, Metcalf Bowler, Jonathan Arnold |

| South Carolina | $60 | 1779-02-08 | $1,000,000 | 1703 |  |

|

John Scott, John Smyth, Plowden Weston |

| Virginia | £3 | 1773-03-04 | £36,384 | 1755 |  |

|

Peyton Randolph, John Blair Jr., Robert Carter Nicholas Sr.(rev) |

Continental Currency: Money for the Revolution

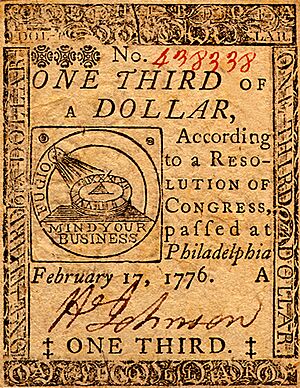

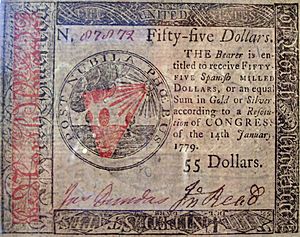

After the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, the Continental Congress started printing its own paper money. This money was known as Continental currency, or simply "Continentals." These bills came in different dollar amounts, from $1⁄6 to $80. During the Revolution, Congress printed a total of $241,552,780 in Continental currency.

The value of Continental currency compared to each state's money was different. For example:

- 5 shillings in Georgia

- 6 shillings in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Virginia

- 71⁄2 shillings in Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania

- 8 shillings in New York and North Carolina

- 321⁄2 shillings in South Carolina

Continental currency lost its value very quickly during the war. This is why people said "not worth a continental." A big problem was that Congress and the states were both printing money without working together. Financial historian Robert E. Wright explains that the bills lost value because "There were simply too many of them." Congress and the states didn't have a good way to take the money out of circulation, either by taxing people or selling bonds.

Another issue was that the British government actively tried to hurt the American economy. They did this by making huge amounts of fake Continental money. Benjamin Franklin later wrote that these fake bills were so well made that they spread everywhere before people realized they were fake. This greatly contributed to the money losing its value.

By the end of 1778, Continentals were worth only about 1⁄5 to 1⁄7 of their original value. By 1780, they were worth only 1⁄40 of their original value. Congress tried to fix the problem by taking old bills out of circulation and issuing new ones, but it didn't work. By May 1781, Continentals were so worthless that people stopped using them as money. Franklin pointed out that the money losing its value was like a hidden tax that helped pay for the war.

Some Quakers, who believed in peace and didn't want to pay war taxes, also refused to use Continentals. At least one Quaker group formally told its members not to use the notes. In the 1790s, after the United States Constitution was approved, Continentals could be exchanged for treasury bonds, but only at 1% of their original value.

After Continental currency failed, Congress chose Robert Morris to be the Superintendent of Finance of the United States. Morris suggested creating the first financial institution allowed by the United States government, the Bank of North America, in 1782. This bank was partly funded by gold and silver coins loaned to the U.S. by France. Morris helped pay for the last parts of the war by issuing notes in his own name. These notes were backed by his personal credit, which was further supported by a French loan of $450,000 in silver coins. The Bank of North America also issued notes that could be exchanged for gold or silver. Morris also oversaw the creation of the first U.S. government mint, which made the first U.S. coins, called the Nova Constellatio patterns, in 1783.

The difficult experience of the Continental dollar's inflation and collapse taught a big lesson. Because of this, the people who wrote the United States Constitution included a rule called the gold and silver clause. This rule said that individual states could not print paper money or use anything other than gold and silver coins to pay debts. However, in a later court case called Juilliard v. Greenman, the Supreme Court decided that this rule did not stop the federal government from printing paper money.

See also

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |