History of the United States dollar facts for kids

The history of the United States dollar started when the Founding Fathers of the United States decided to create a national money system. They based it on the Spanish silver dollar, which had been used in the American colonies for over 100 years.

In 1792, the new Congress passed the Coinage Act of 1792. This law made the United States dollar the official money of the country. It also created the United States Mint to make and spread coins. At first, the dollar's value was linked to both silver and gold. Later, in 1900, it officially became linked only to gold. Finally, in 1971, it stopped being linked to gold at all.

Since the Federal Reserve System was created in 1913, most dollars are printed as Federal Reserve Notes. Today, the United States dollar is the main reserve currency used by governments around the world for international trade.

Contents

Early Money: The Spanish Dollar

The United States Mint started making U.S. dollars in 1792. These new dollars were like the popular Spanish dollar, also known as the piece of eight. Spanish dollars were made in Spanish America and were used widely across the Americas from the 1500s to the 1800s.

The U.S. dollar had a similar amount of silver as the Spanish and Mexican silver dollars. All three types of silver dollars were used together in the United States. The Spanish dollar and Mexican peso were even legal money until the Coinage Act of 1857.

Money During the Revolution

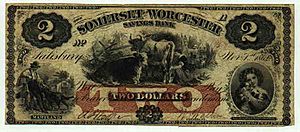

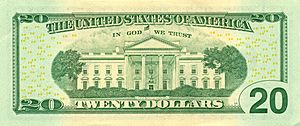

When the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, the Continental Congress started printing paper money called Continental currency, or Continentals. These notes came in different dollar amounts, from $1⁄6 to $80. During the war, Congress printed about $241,552,780 in Continental currency.

By the end of 1778, this money was worth only about 1⁄5 to 1⁄7 of its original value. By 1780, Continentals were worth just 1⁄40 of their face value. Congress tried to fix the money problem by taking old bills out of use and printing new ones, but it didn't work well. By May 1781, Continentals were almost worthless and people stopped using them. Benjamin Franklin said that the money losing its value was like a hidden tax that helped pay for the war.

In the 1790s, after the U.S. Constitution was approved, Continentals could be traded for treasury bonds, but only at 1% of their original value.

After the Continental currency failed, Congress chose Robert Morris to be in charge of the country's money. In 1782, Morris suggested creating the first bank approved by the United States government. This bank, the Bank of North America, got some of its money from France. Morris also helped pay for the last parts of the war by issuing special notes backed by his own money. The Bank of North America also printed notes that could be exchanged for gold or silver.

The big inflation and collapse of the Continental currency made leaders at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 decide to add a "gold and silver clause" to the Constitution of the United States. This rule stopped individual states from printing their own paper money. Article One says that states cannot "make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts."

The Coinage Act of 1792

On July 6, 1785, the Continental Congress officially allowed the creation of a new currency: the United States dollar. The word dollar comes from a German word, Thaler. This term was already common during the colonial period, referring to the Spanish dollar used across the Americas. The Spanish dollar was very popular because it had a lot of silver in it.

In the early 1790s, President George Washington's government, led by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, focused on money issues again. Congress followed Hamilton's advice and passed the Coinage Act of 1792. This law made the dollar the main unit of money for the United States.

The United States Mint was created by Congress after the Coinage Act. Its main job was to make and circulate coins. The first Mint building was in Philadelphia, which was the capital at the time. The Mint was first part of the Department of State. Later, in 1873, it moved to the Department of the Treasury. The Mint could turn any precious metals into standard coins for anyone, without extra charges beyond the cost of cleaning the metal.

Money in the 1800s

In the early 1800s, gold coins became more valuable than their silver equivalents. This caused almost all gold coins to be taken out of use and melted down. So, in the Coinage Act of 1834, the amount of silver to gold was changed from 15:1 to 16:1. This was done by making gold coins lighter. This created a new U.S. dollar backed by a smaller amount of gold. This was the first time the U.S. dollar's value was lowered, by about 6%. After this, both gold and silver coins were useful for buying things.

In 1853, the weight of U.S. silver coins (except the dollar coin, which was rarely used) was reduced. This change effectively put the country on a gold standard, even though it wasn't official yet. Foreign coins, like the Spanish dollar, were also widely used as legal money until 1857.

During the American Civil War, the National Banking Act of 1863 was passed. This law, and later versions, made state bonds and currency disappear by taxing them heavily. The dollar then became the only currency in the United States, and it still is today.

In the 1800s, the dollar was not as accepted worldwide as the British pound. When Nellie Bly traveled around the world in 1889–1890, she carried British pound notes. She also brought some dollars to see if American money was known outside the U.S. Traveling east from New York, she didn't see American money until she found $20 gold pieces used as jewelry in Colombo. There, dollars were accepted but at a 60% lower value.

In 1878, the Bland–Allison Act was passed to allow more silver coins to be made. This law required the government to buy between $2 million and $4 million worth of silver each month and turn it into silver dollars. This helped silver producers, who had political influence.

The discovery of large silver deposits in the Western United States in the late 1800s caused a big political debate. Because so much silver was found, the value of silver in coins dropped a lot. Farmers and groups like the Greenback Party wanted to keep using both silver and gold to make the dollar worth less. This would make it easier for farmers to pay off their debts. On the other side, bankers and business people in the East wanted "sound money" and a switch to the gold standard.

This issue divided the Democratic Party in 1896. It led to the famous Cross of Gold speech by William Jennings Bryan. This debate might have even inspired many ideas in The Wizard of Oz. Despite the arguments, silver's role in money slowly decreased through new laws from 1873 to 1900. In 1900, a gold standard was officially adopted. The gold standard lasted, with some changes, until 1971.

The Gold Standard Era

Note: In this section, 'ounce' means a troy ounce, which is used for precious metals. It's different from the smaller ounce used for other goods.

The system of using both gold and silver lasted until March 14, 1900. That's when the Gold Standard Act was passed. This law said that:

"...the dollar, made of twenty-five and eight-tenths grains of gold (nine-tenths pure), will be the standard value. All money made or printed by the United States will keep the same value as this standard..."

So, the United States officially moved to a gold standard. This meant both gold and silver were legal money, and the dollar was guaranteed to be worth 25.8 grains (about 1.672 grams) of gold. This was a little over $18.60 per ounce of gold.

The gold standard was paused twice during World War I. At the start of the war, U.S. companies owed a lot of money to European businesses. These European businesses started asking for gold to pay off the debts. This caused a lot of gold to leave the U.S. On July 31, 1914, the New York Stock Exchange closed, and the gold standard was temporarily stopped. To protect the dollar's value, the U.S. Treasury Department allowed banks to print emergency money. The new Federal Reserve also set up a fund to help pay foreign debts. These actions worked well, and the gold standard was brought back when the New York Stock Exchange reopened in December 1914.

While the United States stayed neutral in the war, it was the only country that kept its gold standard without limits on gold imports or exports from 1915 to 1917. When the U.S. joined the war, President Wilson stopped gold exports. This paused the gold standard for international trade. After the war, European countries slowly returned to their gold standards, but with some changes.

During the Great Depression, almost every major country stopped using the gold standard. The Bank of England stopped in 1931 because people were demanding gold for their money, which threatened the British money system. This happened in many other countries too. In the United States, the Federal Reserve had to raise interest rates to protect the gold standard for the dollar. This made the already bad economy even worse. After many bank runs in early 1933, people started to hide gold coins. They didn't trust banks or paper money, which made prices fall even more and reduced gold reserves.

The Gold Reserve Act

In early 1933, to fight the severe drop in prices, Congress and President Roosevelt passed several laws and orders. These actions paused the gold standard for most uses, stopped gold from being the only legal way to pay debts, and banned private citizens from owning large amounts of gold coins. These laws included the Emergency Banking Act and the Gold Reserve Act. The U.S. Supreme Court supported these actions in 1935.

For international trade, the dollar's fixed value of $20.67 per ounce of gold was removed. This allowed the dollar's value to change freely in foreign markets. This free-floating system ended after one year. Roosevelt first tried to stop falling prices with the Agricultural Adjustment Act, but it wasn't popular. So, the next popular choice was to make the dollar worth less in foreign markets. Under the Gold Reserve Act, the price of gold was set at $35 per ounce. This made the dollar more attractive to foreign buyers and made foreign money more expensive for those holding dollars. This change led to more gold being converted into dollars, helping the U.S. control much of the world's gold.

Many people in the government and markets at the time thought stopping the gold standard was only temporary. However, bringing it back was seen as less important than dealing with other problems.

After World War II, under the Bretton Woods system, all other countries' money was valued based on the U.S. dollar. This meant they were indirectly linked to the gold standard. The U.S. government had to keep the market price of gold at $35 per troy ounce and also manage conversions to foreign money. By the early 1960s, this became too hard to manage.

In March 1968, the effort to control the private market price of gold was stopped. A two-part system began. In this system, central banks traded gold among themselves at $35 per ounce but did not trade with the private market. The private market could trade at its own price without official interference. The price of gold immediately jumped to $43 per ounce. This two-part system was stopped in November 1973. By then, the price of gold had reached $100 per ounce.

In the early 1970s, prices went up because imported goods, especially oil, became more expensive. Also, spending on the Vietnam War was not balanced by cuts in other government spending. This, along with a trade deficit, made the dollar worth less than the gold that was supposed to back it.

In 1971, President Richard Nixon suddenly stopped the direct exchange of U.S. dollars for gold. This event is known as the Nixon shock.

Dollar Value vs. Gold Value

The quick rise in gold prices after the Bretton Woods system ended happened because the U.S. dollar had lost a lot of its value. This was due to too much money being printed by the Federal Reserve under the old gold standard. Without a fixed link to gold, the dollar became a pure fiat currency, meaning its value was no longer tied to a physical item. As a result, the price of gold went from $35 per ounce in 1969 to almost $500 in 1980.

Soon after the dollar price of gold started to rise in the early 1970s, the price of other goods like oil also began to go up. While prices for goods became more unpredictable, the average price of oil when measured in gold stayed about the same in the 1990s as it had been in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

How Money is Printed

Silver Certificates

United States silver certificates were a type of paper money printed from 1878 to 1964. They were created because some citizens were upset about a law that reduced the use of silver in coins. Silver certificates were used alongside dollar notes that were backed by gold. At first, you could exchange silver certificates for the same value in silver dollar coins, and later for raw silver.

Since the early 1920s, silver certificates were printed in $1, $5, and $10 amounts. In the 1928 series, only $1 silver certificates were made. At that time, most five and ten dollar bills were Federal Reserve notes, which were backed by gold. In 1933, Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which allowed more silver to be put into the market to replace gold. A new 1933 series of $10 silver certificates was printed, but not many were used by the public.

In 1934, a law was passed that changed the wording on Silver Certificates to show where the silver was currently located.

The last government rule about the silver standard was in 1963. President John F. Kennedy signed Executive Order 11110, which gave the Treasury Secretary the power to print silver certificates for any silver the U.S. Government had that wasn't already backing other certificates. This was needed because Kennedy also signed a law that day that ended the Silver Purchase Act of 1934. That act had allowed the Treasury Secretary to buy silver and print certificates for it. Silver certificates continued to be printed for a short time in the $1 amount, but they were stopped in late 1963.

The Dollar as World Money

History

World War II badly damaged economies in Europe and Asia, but the United States' economy was mostly unharmed. As European governments used up their gold and borrowed money from the U.S. for war supplies, the United States gathered large amounts of gold. This gave the U.S. a lot of power after the war.

The Bretton Woods agreement in 1944 made the dollar's importance official. Allied countries wanted to create a global money system that would keep the world economy strong and prevent the problems that followed World War I. The Bretton Woods agreement set up rules for the international economy. It created the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and a system where currency exchange rates were fixed. It valued the dollar at $35 per ounce of gold, and other countries linked their money to the dollar. Some experts say this agreement "dethroned" gold as the main asset.

Even though Bretton Woods made the dollar important, Europe and Asia faced a shortage of dollars. They needed dollars to buy goods from the United States to rebuild after the war. In 1948, Congress passed the Marshall Plan, which gave dollars to European countries. This money helped them buy imports needed to rebuild their economies. The plan helped European countries by giving them dollars to buy goods needed to produce their own exports. Eventually, they could export enough goods to earn the dollars they needed without relying on the Marshall Plan. At the same time, Joseph Dodge worked with Japanese officials to create the Dodge Plan in 1949, which helped Japan in a similar way.

The success of the Marshall and Dodge plans brought new challenges for the U.S. dollar. By 1959, there were more dollars circulating around the world than the U.S. had in gold reserves. This made the gold reserves vulnerable, like a bank run. In 1960, economist Robert Triffin explained the problem to Congress: either the dollar wasn't freely available, and other countries couldn't afford American goods, or the dollar was freely available, but people would lose trust that it could be exchanged for gold.

Eventually, the United States chose to lower the dollar's value. In the early 1960s, U.S. officials mostly stopped people from exchanging dollars for gold through various agreements and policies, like the London Gold Pool. But these actions couldn't last forever; the risk of a run on U.S. gold reserves was too high. When Nixon was elected in 1968, U.S. officials became more worried. Finally, in August 1971, Nixon issued an order that ended the direct exchange of dollars for gold. He said, "We must protect the position of the American dollar as pillar of monetary stability around the world... I am determined that the American dollar must never again be hostage in the hands of the international speculators." This event, known as the Nixon shock, marked the dollar's change from being backed by gold to being a fiat currency.

Impact

The United States gets some benefits because the dollar is the main international reserve currency. For example, the U.S. is less likely to have a major financial crisis related to its international payments.

Today's Money: Fiat Standard

Today, like the money of most countries, the dollar is fiat money. This means it is not backed by any physical asset like gold or silver. If you hold a Federal Reserve note, you cannot demand gold or silver from the government in exchange for it.

In 1963, the words "PAYABLE TO THE BEARER ON DEMAND" were removed from all new Federal Reserve notes. Then, in 1968, you could no longer exchange older Federal Reserve notes for gold or silver. The Coinage Act of 1965 removed all silver from quarters and dimes, which used to be 90% silver. However, some coins, like the Kennedy Half Dollar, were allowed to have 40% silver for a while. Later, even this was removed, with the last silver-content halves made in 1969. All coins that used to be silver for general use are now made of different metals. In 1982, the penny's material changed from copper to zinc with a thin copper coating. The nickel's content hasn't changed since 1866 (except for 1942-1945, when silver and other metals were used to save nickel for war). Silver and gold coins are still made by the U.S. government, but only as special collector's items or commemorative pieces, not for everyday use.

All circulating notes, from 1861 to today, will be accepted by the government at their face value as legal tender. This means the government will take old notes for taxes or fees, or exchange them for new ones. However, they will not exchange them for gold or silver, even if the note says they can be. Some old bills might be worth more to collectors.

As of July 2013, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York said there was $1.2 trillion in U.S. currency circulating worldwide.

Colors and Design of U.S. Money

The U.S. government started printing paper money during the American Civil War. Since cameras at the time couldn't print in color, it was decided that the back of the bills would be a color other than black. The color green was chosen because it represented stability. This started the tradition of printing the back of U.S. money in green. The person who came up with this idea was chemist Christopher Der-Seropian. Unlike money from many other countries, Federal Reserve notes of different values have the same main colors: mostly black ink with green highlights on the front, and mostly green ink on the back. Older bills called "silver certificates" had a blue seal and serial numbers, and "United States notes" had a red seal and serial numbers.

In 1928, the size of bills was made standard, becoming 25% smaller than the older, larger notes (nicknamed "horse blankets"). This new size allowed the Treasury Department to print 12 notes on a sheet of paper that used to only yield 8 notes. Modern U.S. currency, no matter the value, is about 2.61 inches (66.3 mm) wide, 6.14 inches (156 mm) long, and 0.0043 inches (0.109 mm) thick. A single bill weighs about one gram and costs about 4.2 cents for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to make.

Small printing (microprinting) and security threads were added to currency starting with the 1991 series.

Another series of changes began in 1996 with the $100 note. These changes included:

- A larger portrait, moved off-center to make room for a watermark.

- A watermark to the right of the portrait, showing the same historical person as the portrait. You can only see the watermark when you hold the bill up to the light.

- A security thread that glows pink under ultraviolet light. This thread is in a different spot on each bill value.

- Color-shifting ink that changes from green to black when you look at it from different angles. This is in the number on the lower right corner of the bill's front.

- Microprinting in the number in the lower left corner and on Benjamin Franklin's coat.

- Fine lines printed in the background of the portrait and on the back of the note. These are hard to copy well.

- The value of the currency written in a larger font on the back for people with vision problems.

- Other features for machines to check and process the money.

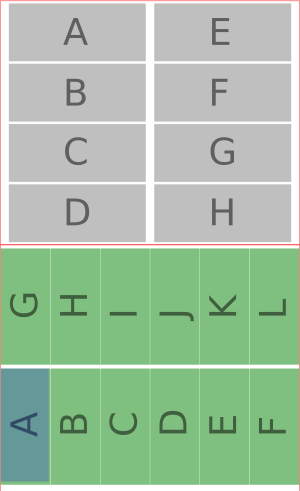

New versions of the 1996 series were released every year. The $50 note came out on June 12, 1997. It had a large dark number with a light background on the back to make it easier to see the value. The $20 note in 1998 added a new feature that machines could read. Its security thread glows green under ultraviolet light, and "USA TWENTY" and a flag are printed on the thread. The microprinting is in the lower left part of the portrait and the lower left corner of the front of the note. In 1998, the $20 note was the most often counterfeited note in the United States. New designs for the $5 and $10 notes were released in 2000.

In 2003, the Treasury announced that it would add new colors to the $20 bill. This was the first U.S. currency since 1905 (not counting some gold certificates from 1934) to have colors other than green or black. The main goal was to stop counterfeiting, not to make it easier to tell different values apart. The main colors of all bills, including the new $20 and $50, are still green and black. The other colors are just subtle shades in smaller design parts. This is different from money like the euro or Australian dollar, which use strong colors to tell each value apart.

The new $20 bills started circulating on October 9, 2003, and the new $50 bills on September 28, 2004. The new $10 notes were introduced in 2006, and redesigned $5 bills began to circulate on March 13, 2008. Each has small elements of different colors but is still mostly green and black. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said when the new $20 bill was shown, "The strength of a nation's money is key to its economy. To keep our money strong, it must be recognized and honored as legal tender, and counterfeiting must be stopped." Before its current design, the most recent redesign of the U.S. dollar bill was in 1996.

The 2008 $5 bill has important new security features. The front of the bill includes yellow printing that helps digital software prevent copying. It also has watermarks, a digital security thread, and tiny microprinting. The back has a large purple number 5 to make it easy to tell apart from other bills.

On April 21, 2010, the U.S. Government announced a heavily redesigned $100 bill. It featured bolder colors, color-shifting ink, tiny lenses, and other features. It was supposed to start circulating on February 10, 2011, but was delayed because of problems with creasing and too much ink on the notes. The redesigned $100 bill was finally released on October 8, 2013. It costs 11.8 cents to make each bill.

Because of a 2008 lawsuit by the American Council of the Blind, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing plans to add a raised texture to the next redesign of each note, except the $1 and the current $100 bill. They also plan larger, higher-contrast numbers, more color differences, and will give out currency readers to help people with vision problems during the change. In 2016, the Treasury announced several design changes for the $5, $10, and $20 bills in this next redesign:

- The back of the $5 bill will show historical events at the Lincoln Memorial. It will include portraits of Marian Anderson (who sang there after being denied a concert hall because of her race), Martin Luther King Jr. (for his famous I Have A Dream speech), and Eleanor Roosevelt (who helped arrange Anderson's performance).

- The back of the $10 bill will show a 1913 march for women's right to vote in the United States. It will also include portraits of Sojourner Truth, Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony, Alice Paul, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

- On the $20 bill, Andrew Jackson will move to the back (smaller, next to the White House), and Harriet Tubman will appear on the front.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |