Edward Spears facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edward Spears

|

|

|---|---|

Sir Edward Louis Spears in court uniform c. 21 May 1942

|

|

| Born | 7 August 1886 Passy, Paris, France |

| Died | 27 January 1974 (aged 87) Ascot, England |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

British Army |

| Years of service | 1903–1919; 1940–1946 |

| Rank | Major-General |

| Unit | 8th Hussars |

| Awards | Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire 1941, Companion of the Order of the Bath 1919, Military Cross 1915, |

| Relations | Married to Mary ('May') Borden-Turner, one son |

| Other work | Chairman of Ashanti Goldfields 1945–1971; Chairman of Institute of Directors 1948–1966 |

| Member of Parliament for Carlisle |

|

| In office 27 October 1931 – 15 June 1945 |

|

| Preceded by | George Middleton |

| Succeeded by | Edgar Grierson |

| Member of Parliament for Loughborough |

|

| In office 15 November 1922 – 9 October 1924 |

|

| Preceded by | Oscar Guest |

| Succeeded by | Frank Rye |

Major-General Sir Edward Louis Spears, 1st Baronet (7 August 1886 – 27 January 1974) was a British Army officer and a Member of Parliament. He was well-known for his important role as a go-between, or liaison officer, connecting British and French forces during both World War I and World War II.

From 1917 to 1920, he led the British Military Mission in Paris. He ended World War I as a Brigadier-General. Between the wars, he served in the British House of Commons. When World War II began, he again became a key link between Britain and France, this time as a Major-General.

Contents

Early Life and Army Start

Edward Spears was born in Paris, France, on August 7, 1886. His parents, Charles McCarthy Spiers and Melicent Marguerite Lucy Hack, were British. His grandfather, Alexander Spiers, was famous for creating a successful English-French dictionary.

Edward changed his last name from Spiers to Spears in 1918. He said it was because people often mispronounced Spiers. As a child, he was often sick. But after attending a tough boarding school in Germany, he became stronger. He also learned to speak German.

Joining the Army

In 1903, Edward joined the Kildare Militia in Ireland. He was nicknamed "Monsieur Beaucaire" because he was so polite and French-speaking. In 1906, he became an officer in the regular army with the 8th Royal Irish Hussars.

Spears was not a typical army officer. He translated French military books, showing his deep knowledge. In 1911, he worked at the War Office in London. There, he helped create a secret codebook for both British and French forces. In May 1914, he went to Paris to work with the French Ministry of War. When World War I started in August 1914, he was sent to the front lines. He proudly said he was the first British officer there.

World War I: Bridging the Gap

During World War I, it was hard for British and French armies to work together. Many officers did not speak each other's languages well. For example, Field Marshal Sir John French, the British commander, spoke French so poorly that people thought he was speaking English.

British soldiers even made up their own funny names for French towns, like "Wipers" for Ypres. Edward Spears, who spoke both languages fluently, became very important. Even though he was a junior officer, he met many top British and French leaders. This helped him greatly throughout his life.

First Liaison Duties

On August 14, 1914, Spears was sent to the Ardennes region. His job was to connect Field Marshal Sir John French with General Charles Lanrezac of the French Fifth Army. This was difficult because Lanrezac was very secretive and sometimes rude to the British.

The German army was moving fast, so commanders had to make quick decisions. Spears often had to drive between headquarters. He traveled on roads filled with refugees and retreating soldiers. Sometimes, he was even connected to German lines by mistake on the phone! He tried to pretend to be German to get information, but it didn't work.

Saving an Army

On August 23, General Lanrezac suddenly decided to retreat. This would have left the British forces dangerously exposed. Spears quickly told Sir John French, saving the British army. The next day, Spears bravely urged Lanrezac to counter-attack. He told the General that if the British army was destroyed, England would never forgive France.

Spears continued to speak his mind. When a new French general, Louis Franchet d'Espèrey, wrongly thought the British were retreating, he criticized them. Spears demanded an apology, which he got. Spears stayed with the French Fifth Army during the First Battle of the Marne. He even rode behind Franchet d'Espèrey when Reims was freed.

Working with Churchill

After being wounded, Spears returned to the front in April 1915. He went on a tour with Winston Churchill, who was then in charge of the British Navy. Spears often felt alone as the only Englishman among French officers. He heard many complaints that Britain was not doing enough.

Spears was wounded again in August 1915. When he returned, he found British and French generals arguing. His job was to improve their relationship. In December, Winston Churchill arrived in France. He had lost his job in the Navy and wanted to fight on the Western Front. Spears and Churchill became good friends. Churchill even wanted Spears to join his team if he got a command. However, Spears' liaison work was too important.

Fears and High-Level Work

Spears knew General Philippe Pétain, a hero of the Battle of Verdun. But when the British suffered heavy losses at the Battle of the Somme, Spears heard hints that they couldn't handle the fighting. He worried about his own countrymen's courage. By August 1916, he felt so much pressure from both sides that he feared a mental breakdown.

In May 1917, Spears was promoted to Major. He moved to Paris for a high-level job. He was to connect the French Ministry of War with the British War Office in London. In just three years, he had met many powerful people. Paris was full of plots and rival groups, but Spears used this to his advantage.

He was told to report directly to London, bypassing other officials. Soon after, General Pétain, the new French Commander in Chief, wanted Spears' boss, General Henry Wilson, replaced. Spears protested but was overruled. This made Wilson his enemy.

Reporting on French Problems

By May 22, 1917, Spears learned about mutinies in the French Army. He went to the front to see for himself. These mutinies had started after terrible losses in battles like Verdun. Spears was called to London to tell the British government about the low morale of the French troops. This was a huge responsibility.

He told Prime Minister David Lloyd George that the French army would recover. Lloyd George kept asking for assurances. Spears famously replied, "The fact that you ask me that shows you know the meaning of neither," when asked for his word of honor.

Spears also heard about French unhappiness with Britain's efforts. They felt Britain had suffered fewer casualties and held a much shorter front line. Spears worked to improve relations and also helped with the Polish army.

Clemenceau and Intrigues

In November 1917, Georges Clemenceau became Prime Minister of France. He was determined to fight on. Spears reported that Clemenceau, who spoke English well, was "pro-English." Clemenceau told Spears he could visit him anytime. Spears used this to introduce his friend Winston Churchill to the powerful French leader.

Spears saw Clemenceau's tough side, calling him "probably the most difficult and dangerous man I have ever met." He reported to London that Clemenceau wanted to control the Supreme War Council.

General Henry Wilson, Spears' enemy, called him a "mischief-maker." In January 1918, Spears was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and then Brigadier-General. But his career seemed in danger when Henry Wilson became the new Chief of the Imperial General Staff.

General Ferdinand Foch, an ally of Wilson, became the Allied Supreme Commander. Foch tried to limit Spears' access to information. But Spears used his strong connection with Clemenceau to keep his position. He argued that he worked for Clemenceau, not Foch.

As the Germans advanced in March 1918, Paris was bombed. Both sides blamed each other. Spears was viewed with suspicion by both the French and British. Lord Derby, the British ambassador, said Clemenceau turned against Spears because Spears was telling the British government things Clemenceau didn't want them to know.

Even after the war ended in November 1918, bad feelings remained. Clemenceau did not even mention the British in his victory speech.

Between the Wars: Politician and Author

Spears left the army in June 1919. He then became involved in business and politics.

Business and Politics

In 1921, Spears started a business in the new country of Czechoslovakia. He met important Czech leaders and became chairman of the British Bata shoe company in 1934. He also became a director of a Czech steel works.

His support for Czechoslovakia made some British politicians suspicious. He strongly opposed the Munich agreement of 1938, which gave part of Czechoslovakia to Germany. He was heartbroken by the news. His views put him against many Conservatives who supported the agreement.

Member of Parliament

Spears was a Member of Parliament (MP) twice. First, for Loughborough from 1922 to 1924. Then, for Carlisle from 1931 to 1945. Because of his strong pro-French views, he was nicknamed "the Member for Paris."

He was first elected in 1922 without opposition. His first speech in Parliament criticized both the British Foreign Office and the Embassy in Paris. He also spoke against the French occupation of the Ruhr region in Germany. He lost his seat in 1924.

In 1931, he was elected MP for Carlisle. He became chairman of the European Study Group in 1936. This group included MPs who were worried about Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain's policies towards Europe.

Books on World War I

In 1930, Spears published Liaison 1914. This book was about his experiences as a liaison officer in the early months of World War I. Winston Churchill wrote the foreword. The book was well-received and praised the British Expeditionary Force. It also described the horrors of war. A French translation was also successful.

In 1939, he published Prelude to Victory. This book covered early 1917 and the Calais Conference. Spears wrote it as war was approaching again, hoping it would offer lessons for British-French relations.

Against Appeasement

Spears joined groups of MPs who were against appeasement. This policy aimed to avoid war by giving in to some of Germany's demands. He was part of the "Eden Group" and "The Old Guard," both of which called for Britain to rearm against Nazism.

Just before World War II, in August 1939, Spears visited the Maginot Line in France with Winston Churchill. He suggested a plan to float mines down the Rhine river to damage German bridges. Churchill later approved this plan, called Operation Royal Marine.

World War II: Churchill's Man in France

The Phoney War

During the "Phoney War" (the quiet period at the start of World War II), Spears wanted Britain and France to take more action. He was frustrated that they were only dropping leaflets instead of bombing Germany. He urged support for Poland.

As chairman of the Anglo-French Committee in the House of Commons, he kept in touch with his French friends. In October 1939, he led a group of MPs to visit the French Parliament and the Maginot Line.

In February 1940, Spears checked on Operation Royal Marine for Winston Churchill. The operation involved releasing thousands of mines into the Rhine. The French initially stopped it, fearing German attacks. But it was launched on May 10, 1940. It worked, but by then, the German Blitzkrieg was already crushing France.

Churchill's Representative

Spears Goes to Paris

On May 22, 1940, Winston Churchill sent Spears to France. German forces were rapidly advancing, and reports were confusing. Spears was to be Churchill's personal representative to Paul Reynaud, the French Prime Minister. Three days later, Spears, now a Major-General, flew to Paris.

He met with French leaders during the chaos. He suggested ways to stop tanks and destroy fuel supplies. He met Marshal Philippe Pétain, who treated him like a son. But Spears felt Pétain seemed paralyzed by the situation. He realized how hard it was to rebuild the strong connections he had in World War I.

French Despair

On May 27, Churchill asked Spears to fight against defeatism. Reynaud spoke of "mortal danger" from Italy, which had not yet joined the war. Spears thought Italy's entry might even help morale. Reynaud and Spears argued about British air support. Spears compared the spirit of Paris in 1940 unfavorably to 1914.

That evening, Spears heard about Belgium's sudden surrender. He was briefly encouraged but then annoyed by French criticism of the British commander. Spears felt a "break in the relationship" between the two nations.

On May 28, Reynaud asked about appealing to the United States for help. Spears said it was unlikely to work. He also welcomed the idea of a German invasion of Britain, believing Britain could easily defeat it at sea.

Supreme War Council Meetings

On May 31, 1940, Churchill flew to Paris for a meeting of the Anglo French Supreme War Council. Spears was there, taking notes. They discussed evacuating troops from Narvik and the Dunkirk evacuation. The French complained that far more British soldiers had been evacuated from Dunkirk than French. Churchill promised that British and French soldiers would now leave together.

Churchill spoke passionately about the need for both countries to fight on. Spears was deeply moved by Churchill's words. After the meeting, some French officials talked about France seeking a separate peace. Spears warned that Britain would blockade France if that happened. Churchill declared Britain would fight on no matter what.

Last-Ditch Talks

On June 7, Spears flew to London with a message from Reynaud. The French wanted more British divisions and fighter squadrons. Spears returned to France with Churchill on June 11 for another meeting at Briare. General Charles de Gaulle was also there; Spears was impressed by him.

Spears realized that "the battle of France was over." The next day, General Weygand's grim report confirmed his fears. Spears felt the two countries were at a "cross-roads" where their paths might split.

After Churchill left, Spears argued with Marshal Pétain, who believed an armistice was unavoidable. Pétain said, "You cannot beat Hitler with words." Spears felt Pétain was hostile. He then drove to Tours to find the British Ambassador.

The Final Meeting at Tours

The final meeting of the Anglo French Supreme War Council took place at Tours on June 13. Reynaud said France would have to give up unless the US gave immediate help. Spears noted Churchill's determination: "We must fight, we will fight, and that is why we must ask our friends to fight on."

Reynaud acknowledged Britain would continue the war. He said France would continue from North Africa, but only if America joined. He asked Britain to release France from its promise not to make a separate peace. Spears passed a note to Churchill, suggesting a break.

During the break, Spears told Churchill that Reynaud's mood had changed. He was sure de Gaulle was loyal. When the meeting resumed, both countries agreed to send similar telegrams to the US.

A Misunderstanding

After the meeting, de Gaulle told Spears that a French official was saying Churchill had agreed to France seeking a separate armistice. Spears realized there had been a misunderstanding. When Reynaud spoke in French about an armistice, Churchill had said, "Je comprends" (I understand), meaning "I understand what you are saying," not "I agree."

Spears got Churchill to confirm he had not agreed to a separate armistice. But the damage was done. The misunderstanding was later used by a French Admiral to tell French warships that Churchill had agreed to France ending the fight.

Churchill flew back to London without speaking to the French cabinet, as Reynaud had promised. The French ministers were upset and felt abandoned. Spears believed this helped sway them towards surrender. He felt that by June 13, the chance of France staying in the war was almost gone.

Bordeaux and the Union Offer

On June 14, Spears went to Bordeaux, where the French government had moved. Paris had fallen that morning. Spears found Reynaud exhausted and undecided. The British consulate was full of refugees trying to leave France.

Spears argued with French officials who seemed ready to give up. He praised the spirit of French soldiers from World War I. He was outraged that French commanders in North Africa were against receiving more troops from France. He wondered why Reynaud didn't fire generals who were defeatist.

Spears and the Ambassador sent a telegram to London. They said everything depended on US help. They also said they would try to get the French fleet to join the British. They had little confidence left.

British Refusal and Union Proposal

By June 16, Spears was sure that if France asked for an armistice, they would never fight again. Britain took a firm stance, saying France could still fight with its overseas territories and fleet. Reynaud's mistress, Hélène de Portes, kept interrupting meetings, annoying Spears. He felt her influence harmed Reynaud.

Later, a telegram arrived from London. Britain would agree to France seeking armistice terms, but only if the French fleet sailed to British harbors immediately. Reynaud was insulted. He spoke to Churchill by phone and asked Spears to arrange a meeting at sea. But it never happened.

That afternoon, Spears and the Ambassador met Reynaud. They conveyed a message from London about moving the French fleet and air force. While they argued, de Gaulle called from London with an amazing proposal: a Franco-British Union. "France and Great Britain shall no longer be two nations, but one," the declaration said. Spears was "transfixed with amazement." Reynaud was thrilled.

However, the French cabinet rejected the offer. One minister said it would make France a British "Dominion." Reynaud resigned. Spears felt the rejection was like "stabbing a friend." Churchill, who was already on a train to meet them, returned to London with a "heavy heart."

De Gaulle's Escape

In Bordeaux, de Gaulle told Spears he feared arrest. Reynaud confirmed that Pétain would form a new government of "defeatists." Spears decided to help de Gaulle escape to Britain. He called Churchill, who reluctantly agreed to take de Gaulle.

On June 17, de Gaulle and his aide went with Spears to the airfield. They pretended de Gaulle was just seeing Spears off. After a delay, their plane took off for Britain. Churchill later wrote that Spears personally rescued de Gaulle. Once in Britain, de Gaulle gave Spears a signed photo, calling him "witness, ally, friend."

Spears and De Gaulle in the Levant

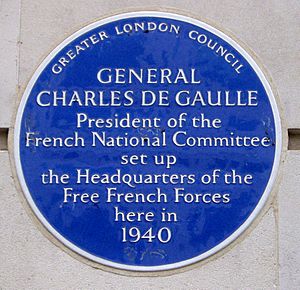

In late June 1940, Spears was appointed head of the British government's mission to de Gaulle. De Gaulle's headquarters were set up in London.

After Dunkirk and Mers el Kebir

Over 100,000 French troops were evacuated from Dunkirk, but most returned to France. On July 3, Spears had the difficult job of telling de Gaulle about the British attack on French ships at Mers El Kébir in North Africa. This attack, called Operation Catapult, sank many French warships and killed many French sailors. It caused great anger towards Britain and made it harder for de Gaulle to recruit men.

De Gaulle saw the naval action as "inevitable" but was unsure if he could still work with Britain. Spears tried to encourage him.

Dakar and Syria

Churchill wanted the Free French to take over French colonies from the Vichy regime. The target was Dakar in West Africa. Spears went with de Gaulle on this mission (Operation Menace). However, the mission failed. De Gaulle was further discredited, and he began to criticize Spears.

Still working as Churchill's representative, Spears went to the Levant (Middle East) with de Gaulle in March 1941. They met British officers and General Georges Catroux, who supported de Gaulle.

Spears and de Gaulle argued for a strong approach against Vichy French forces. They believed it was important to prevent Germans from using French air bases in Syria. Spears also complained that a French ship was allowed to sail between Beirut and Marseille, carrying goods and French prisoners who supported the British.

On May 13, 1941, German planes landed in Syria. This confirmed the fears of de Gaulle and Spears. On June 8, Allied troops invaded Lebanon and Syria. Spears noted the "strange class of Frenchmen who had developed a vigour in defeat."

In January 1942, Spears was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE). He became the first British minister to Syria and Lebanon. A major street in Beirut is still named after him.

Later Life

Spears lost his seat in Parliament in the 1945 election. That same year, he became chairman of Ashanti Goldfields, a mining company. From 1948 to 1966, he was chairman of the Institute of Directors. He also wrote several books after the war, including his autobiography, The Picnic Basket.

In 1947, he founded the Anglo-Arab Association. He was made a baronet in 1953. Sir Edward Louis Spears died on January 27, 1974, at the age of 87. He is buried at Warfield, England, with his first wife, May, and their son, Michael.

Linguistic Skills

Spears was very good at languages. In October 1939, he spoke on French Radio. Listeners were so surprised by his perfect French that they thought someone else was reading for him! He even took lessons with a French elocution teacher. He also spoke some German from his time at school there.

Despite his fluency, Spears disliked being an interpreter. He knew it took more than just knowing two languages. At the crucial Tours conference on June 13, 1940, he had the huge responsibility of translating between Paul Reynaud and Winston Churchill. The fate of two nations was at stake. He knew others in the room understood both languages, making his job even more stressful.

Media Appearances

Sir Edward Spears appeared in several documentaries. He was interviewed in the 1964 series The Great War, talking about his role as a liaison officer. He also appeared in the 1969 French-West German documentary The Sorrow and the Pity and the 1974 series The World at War.

Images for kids

-

When Winston Churchill (seen here with Admiral 'Jackie' Fisher) lost his post as First Lord of the Admiralty after the failure of the Gallipoli campaign, he served on the western front. Spears escorted him during his first visit and they became friends – a relationship that would see Spears appointed WSC's special representative to de Gaulle and the Free French in the Second World War.

-

Georges Clemenceau, Prime Minister of France from 16 November 1917 to 20 January 1920. He supported Spears when Foch tried to have him removed. Known as 'The Tiger of France', he was a formidable character – Spears would later refer to what he had said of himself, "I had a wife, she abandoned me; I had children, they turned against me; I had friends, they betrayed me. I have only my claws left, and I use them."

-

Lady Spears (centre) with Sir Edward Spears (left) in December 1942 in Lebanon on the steps of their residence – that of the First British Minister to the Levant. To the right of Sir Edward stands Henry Hopkinson, private secretary to the Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Sir Alexander Cadogan; Richard Casey, Minister Resident in the Middle East, is to the right of Lady Spears, with Mrs Ethel (Maie) Casey to her left.

-

The de Havilland Flamingo transport aircraft. Churchill's personal Flamingo, in which he flew to and from France during the crisis of May and June 1940, was operated by No. XXIV Squadron RAF.