Energy policy of the United Kingdom facts for kids

The energy policy of the United Kingdom is all about how the UK manages its energy. This includes making sure there's enough energy for everyone, helping people who struggle to pay for heating, and using energy more wisely. The UK has made good progress, but still uses a lot of energy.

A big goal for the UK is to cut down on carbon dioxide emissions, which are gases that cause climate change. It's not always clear if the plans in place are enough to reach this goal. The UK used to produce a lot of its own oil and gas from the North Sea, but that's decreasing. So, the country now relies more on energy from other places.

The UK has also tried to make public transport better in cities. However, it hasn't focused as much on encouraging hybrid vehicles or ethanol fuel, which could help reduce how much fuel cars use. For renewable energy, like wind and tidal energy, the UK had a goal for 20% of its energy to come from these sources by 2020.

Today, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) is in charge of energy policy. The Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem) makes sure energy markets are fair. Since the electricity and gas companies became private in the 1980s, UK governments have focused on managing energy prices, reducing carbon, rolling out smart meters, and making buildings more energy efficient.

Contents

- UK Energy Goals

- Net Zero Strategy

- Energy Markets

- UK Electricity Sources

- How the UK Uses Energy

- History of Energy Policy

- Energy Supply and Decarbonisation Policy

- Early 2000s: Climate Change Becomes a Priority

- Energy White Paper, 2003

- EU Emissions Trading Scheme 2005

- Energy Review, 2006

- Energy White Paper, 2007

- Climate Change Act, 2008

- UK Low Carbon Transition Plan, 2009

- 2011 White Paper

- Feed-in Tariff

- Emissions Performance Standard

- Energy Bill, 2012–2013

- Select Committee Report, 2016

- Salix Finance Ltd.

- Energy White Paper, 2020

- Government Oversight of Energy

- Support for Fossil Fuels

- Renewable Energy Targets

- Fuel Poverty

- Oil and Gas

- Images for kids

- See also

UK Energy Goals

In 2007, a government paper called "Meeting the Energy Challenge" set out the UK's main energy goals. These goals aimed to:

- Cut carbon dioxide emissions by 60% by 2050, with good progress by 2020.

- Keep energy supplies reliable.

- Encourage fair competition in energy markets to help the economy grow.

- Make sure every home could be heated properly and affordably.

Energy policy covers how electricity is made and sent out, how much fuel transport uses, and how homes are heated (often with Natural Gas). The government knows that energy is vital for daily life and the economy. It faces two main challenges:

- Dealing with climate change by reducing carbon dioxide.

- Making sure there is secure, clean, and affordable energy, especially as the UK imports more fuel.

The UK also needs to build many new power stations in the next 20 years. This is because many old coal and nuclear power stations built in the 1960s and 1970s are closing down.

In 2006, the idea of building new nuclear power stations came up again. After some legal challenges, the government decided in 2008 that new nuclear power stations were important for fighting climate change and ensuring energy supply. The Energy Bill 2008 updated laws to support this.

In 2008, the Department of Energy and Climate Change was created. This department brought together energy policy and climate change mitigation policy.

Scotland's Energy Approach

Even though the UK government handles most energy policy, the Scottish Government has its own energy policy. Scotland's policy is different from the UK's, and it has the power to put some of its energy priorities into action.

Net Zero Strategy

In 2021, the UK government released its Net-Zero strategy. This plan aims to reduce the country's emissions to net zero by 2050, compared to 1990 levels. The strategy explains how different parts of the UK, like power, transport, and buildings, will reach net-zero. This policy is part of climate action to meet the Paris Agreement goal of stopping dangerous climate change. It updates the Climate Change Act 2008.

Energy Markets

In 2006, the total value of energy used in the UK was estimated at about £130.73 billion. Transport used the most energy outside of the energy industry itself. The UK is currently making big changes to its electricity market. These changes include using "contracts for difference" for power generators and a "capacity market" to ensure there's enough electricity supply in the future.

UK Electricity Sources

The amount of electricity the UK used became stable in 2017, reaching 307.9 terawatt-hours (TWh). This was a 12% drop from 2007. Homes, businesses, and industries each used about one-third of the electricity. Industrial use dropped by 18%, and home use decreased by 14% due to higher prices and more energy-efficient appliances.

In 2017, the UK got its electricity from these main sources:

- Natural gas: 40.8%

- Renewables: 30.8%

- Nuclear: 21.0%

- Coal: 6.9%

- Oil: 0.5%

Coal Power

In November 2015, the UK government announced that all coal-fired power stations would close by 2025. Many have already closed, like Ironbridge in 2015, and Rugeley, Ferrybridge, and Longannet in 2016. Eggborough closed in 2018 and is being changed to a gas power station. Lynemouth was converted to run on biomass in 2018, and Uskmouth is also being converted. Cottam closed in 2019, and Kilroot was also set to close.

In May 2016, for the first time, solar power produced more electricity than coal. On April 21, 2017, the UK went a full 24 hours without using any coal power for the first time since the 1800s. By 2018, coal use was at historic lows. Coal provided only 5.4% of UK electricity in 2018, down from 30% in 2014.

Gas Power

In the 1980s and early 1990s, there was a huge increase in gas-fired power stations, known as the "Dash for Gas." These plants were quick to build, which was helpful when interest rates were high.

Natural gas is expected to play a smaller role in the UK's energy future. Production from North Sea gas fields continues to drop. While there's investment in pipelines to import natural gas (mostly from Norway), the UK wants to avoid relying too much on countries like Russia for its energy.

By 2021, North Sea oil and natural gas production was predicted to fall by 75% from 2005 levels. Europe's oil and coal reserves are very low compared to how much is used.

In November 2015, a new "dash for gas" was announced. This was needed to fill the energy gap as coal power stations closed and new nuclear ones were delayed.

Nuclear Power

After the UK government decided in January 2008 to support new nuclear power stations, EDF planned to open four new plants in the UK by 2017. However, it's unlikely that more nuclear power stations will be built in Scotland, as the Scottish Government is against them.

Renewable Energy

Since the mid-1990s, renewable energy has grown in the UK, adding to the small amount of hydroelectricity already produced. Renewable sources provided 6.7% of the UK's electricity in 2009, rising to 11.3% in 2012.

By mid-2011, the UK had over 5.7 gigawatts of wind power in the United Kingdom capacity, making it the world's eighth largest wind power producer. Wind power is expected to keep growing. In the UK, wind power is the second biggest renewable energy source after biomass.

| Source | GWh | % |

|---|---|---|

| Onshore wind | 12,121 | 29.4 |

| Offshore wind | 7,463 | 18.1 |

| Shoreline wave/tidal wind | 4 | 0.0 |

| Solar photovoltaics | 1,188 | 2.9 |

| Small scale hydro | 653 | 1.6 |

| Large scale hydro | 4,631 | 11.2 |

| Bioenergy | 15,198 | 36.8 |

| Total | 41,258 | 100 |

In 2017, renewable energy made up 9.7% of the UK's total energy supply. This was similar to the 9.9% average for other countries. Renewables also produced 29.6% of the UK's total electricity, which was more than the 24.6% average for other countries.

Since 2020, there has been an increase in large-scale battery storage to help manage the changing supply from wind and solar power. As of May 2021, 1.3 GW of grid storage batteries were active, along with traditional pumped storage at Dinorwig, Cruachan, and Ffestiniog.

How the UK Uses Energy

- See main article Energy use and conservation in the United Kingdom

In 2005, the UK used its energy like this:

- Transport: 35%

- Space heating: 26%

- Industry: 10%

- Water heating: 8%

- Lighting/small electrics: 6%

People in the UK are using more fuel because they are more mobile and have more money. Fuel use increased by 10% in the decade leading up to 2000. This trend is expected to slow down as more efficient diesel and hybrid vehicles are used.

Homes in the UK use a lot of energy for heating, more than in warmer places like the US or southern Europe. The UK has rules to encourage energy conservation in buildings, especially for new homes and businesses. For example, buildings in England and Wales have needed an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) since June 2007 before they are sold or rented.

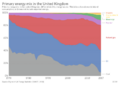

In 2017, the UK's total energy supply mainly came from natural gas (38.6%) and oil (34.5%). Nuclear energy was 10.4%, coal was 5.4%, and electricity was a small 0.7%. Renewables, including biofuels, wind, solar, and hydro, made up 10.4%. Overall, the total energy supply had dropped by 16.7% since 2007.

History of Energy Policy

Market Changes in the 1980s

In the 1980s and 1990s, the government changed its policy to make energy markets more open. This involved selling off state-owned energy companies and closing the old Department of Energy. Because of this, the government can no longer directly control energy markets. Instead, organizations like Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem) in Great Britain regulate them. The government now influences the market through taxes, subsidies, and planning rules.

1990s to 2000s: Focus on Consumers

The government continued to make changes in the 1990s to create a competitive energy market. In 1994, VAT (a type of tax) was first added to home energy bills. When the Labour Government came to power in 1997, it kept the idea of a competitive market but also wanted to help the poorest families and protect the environment.

The Labour Government introduced Winter Fuel Payments for people over 60. The Utilities Act 2000 created Ofgem to regulate the market and Energywatch to protect consumers. By 1999, all UK households could switch their gas or electricity supplier. Many people switched to save money. By the mid-2000s, the market was mostly controlled by six big energy companies, often called the "Big Six."

The Warm Homes and Energy Conservation Act 2000 aimed to end "fuel poverty" by 2016. Fuel poverty means a household with a low income cannot afford to keep their home warm. In 2008, Ofgem investigated competition in the energy market. It found some issues that made competition weaker but no evidence of a cartel or that price rises were unfair.

2010 to 2017: Price Concerns

The Energy Act 2010 introduced the Warm Home Discount scheme in 2011. This made big energy suppliers legally responsible for helping people in fuel poverty. Ofgem also reviewed the market and found that it was too complicated for consumers. Many customers were on more expensive "standard" tariffs instead of cheaper fixed-term ones. Prices also seemed to go up quickly but fall slowly.

The government wanted to force energy suppliers to offer their cheapest tariffs. The Energy Act 2013 gave Ofgem more power. In 2014, the government updated its fuel poverty strategy to improve energy efficiency in homes by 2030.

In 2013, Ed Miliband, then leader of the Labour Party, suggested freezing energy bills for 20 months if his party won the next election. This idea was popular with the public but criticized by energy companies. By the end of the year, the government admitted that many people felt big energy suppliers were overcharging.

In 2014, Ofgem asked the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) to investigate the energy market. In 2015, the CMA reported that energy suppliers might be overcharging customers by as much as £1.7 billion. The CMA suggested a price cap for customers with prepayment meters, but some felt it didn't go far enough.

2018 to Present: Energy Price Cap

Before the 2017 United Kingdom general election, Prime Minister Theresa May promised to put a price cap on energy bills. She said the market wasn't working for families and that a cap could save households up to £100. The Domestic Gas and Electricity (Tariff Cap) Act 2018 became law in July 2018.

In August 2022, the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats called for the energy price cap to be "frozen" to help with the cost of living. In September 2022, the government announced an "energy price guarantee" to limit typical household energy costs. This was initially planned for two years but was later reduced to six months.

2022–23: Government Support for Households

To help with rising energy costs, the government announced support measures. In February 2022, there was a £200 discount on energy bills (later changed to a non-repayable £400 grant) and a £150 council tax rebate for many homes. More support was announced in May, including payments for low-income households and pensioners.

In September 2022, Prime Minister Liz Truss announced the "Energy Price Guarantee" to limit typical household energy costs to £2,500 per year. This support was also offered to businesses. The cost was uncertain but estimated to be over £100 billion per year. The duration of this guarantee was later reduced to six months, ending in April 2023, but in March 2023, the Chancellor kept the subsidy at the £2,500 level until the end of June.

Energy Supply and Decarbonisation Policy

Early 2000s: Climate Change Becomes a Priority

In 2005, Gordon Brown asked Nicholas Stern to study the economics of climate change. The Stern Report said that climate change was the "greatest... market failure ever seen." The UK, along with over 170 other nations, promised to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. In 2003, the UK produced 4% of the world's greenhouse gases. The long-term goal is to cut carbon emissions by 80% by 2050. Europe developed a system for trading carbon emission credits to help with this.

Road transport emissions have been reduced since 1999 by linking Vehicle Excise Duty (car tax) to how much CO2 a vehicle theoretically emits. Aviation fuel is not covered by the Kyoto Protocol. This means that if the UK successfully cuts other carbon emissions, aviation could cause 70% of the UK's allowed CO2 emissions by 2030.

Energy White Paper, 2003

In 2003, the UK government published its "Our Energy Future – creating a Low Carbon Economy" paper. This was the first formal energy policy for the UK in 20 years. It recognized that reducing carbon dioxide (the main gas causing global climate change) was necessary. It committed the UK to a 60% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions by 2050 and saw business opportunities in this. The paper focused on "cleaner, smarter energy" and was based on four ideas: environment, reliable energy, affordable energy, and competitive markets.

EU Emissions Trading Scheme 2005

The European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) started in 2005. It's a system where there's a limit (cap) on emissions, and companies can buy and sell permits to emit carbon (trade). This system aims to make the price of carbon go up, so companies have a reason to reduce their emissions. The idea is that it's cheaper to reduce emissions now than to deal with climate change later.

The EU ETS sets an overall limit on emissions and gives tradable permits to companies. If a company wants to emit more than its limit, it has to buy permits from another company that doesn't need all of its permits. The price of carbon slowly increases as fewer permits are available. This encourages businesses to find low-carbon ways of working.

Energy Review, 2006

In 2006, the UK government reviewed its energy policy because the world energy situation was changing quickly. The UK was relying more on imported oil and gas, there were concerns about carbon emissions, and more investment was needed in power stations. One part of the review looked at developing nuclear power. The consultation process for this was criticized, and plans for new nuclear plants were delayed until a proper consultation could be done.

The 2006 Energy Review had four main goals:

- Cut carbon dioxide emissions by about 60% by 2050, with good progress by 2020.

- Keep energy supplies reliable.

- Promote competitive markets to help economic growth.

- Ensure every home is heated properly and affordably.

The review also highlighted two major challenges:

- Tackling climate change as global carbon emissions grow.

- Providing secure, clean, and affordable energy as the UK imports more.

The review suggested three main areas of action:

- Saving Energy: This means using less energy in homes and businesses. Ideas included providing more information, setting higher standards for goods, and focusing on energy-efficient transport.

- Cleaner Energy: This involves making the energy used cleaner. Ideas included more local energy production, using combined heat and power (CHP), strengthening the Renewables Obligation, and supporting carbon capture and storage.

- Energy Security: This means having good access to fuel supplies and the right infrastructure. Many actions to reduce carbon emissions also help with energy security by creating a mix of energy sources.

Energy White Paper, 2007

The 2007 energy white paper, "Meeting the Energy Challenge," was published in May 2007. It outlined the government's plan to deal with two main challenges:

- Cutting carbon emissions to fight global warming.

- Ensuring secure, clean, and affordable energy as production from North Sea oil and gas declines.

The paper expected that 30–35 GW of new electricity generation capacity would be needed within 20 years. This was to fill the energy gap from increased demand and the closure of existing power plants. It also noted that, with existing policies, renewable energy would likely only provide about 5% of the UK's energy by 2020, not the 20% target mentioned in the 2006 review.

Proposed Energy Strategy

The government's strategy had six parts:

- Creating international rules to fight climate change.

- Setting legally binding carbon targets for the UK economy through the United Kingdom Climate Change Bill.

- Making energy markets more competitive and open.

- Encouraging more energy saving through better information and rules.

- Supporting low-carbon technologies, including research and development.

Practical measures included:

- For Businesses: A new mandatory "Carbon Reduction Commitment" for large energy users, Energy Performance Certificates for business buildings, and smart meters for most businesses within five years.

- For Homes: New homes to be zero-carbon buildings by 2016, improving existing homes' energy efficiency, and possibly phasing out inefficient light bulbs by 2011.

- For Transport: A new strategy for low-carbon transport and including aviation in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme.

- Energy Supply: A plan to increase the use of biomass, support for local electricity and heat generation, and a goal for renewable energy to supply 10% of electricity by 2010 and an "aspiration" for 20% by 2020. It also supported new nuclear power stations and biofuels for transport.

Scottish Government's Response

The Scottish Government responded to the UK paper by stating it was against new nuclear power stations in Scotland and had the power to stop them.

Climate Change Act, 2008

The Climate Change Act 2008 became law in November 2008. It set a framework to cut the UK's carbon emissions by 80% by 2050 (compared to 1990 levels), with an interim target of 26% to 32% by 2020. Reducing carbon from electricity generation was seen as a key part of this. The UK was the first country to set such a long-term and legally binding carbon reduction target. The Committee on Climate Change was launched in December 2008 to oversee this. In April 2009, the government set a requirement for a 34% cut in emissions by 2020.

UK Low Carbon Transition Plan, 2009

Published in July 2009, the UK Low Carbon Transition Plan detailed actions to cut carbon emissions by 34% by 2020. By 2020, it aimed for:

- Over 1.2 million "green jobs."

- 7 million homes to have improved energy efficiency, with over 1.5 million generating renewable energy.

- 40% of electricity to come from low-carbon sources (renewables, nuclear, clean coal).

- Gas imports to be 50% lower.

- New cars to emit 40% less carbon than in 2009.

2011 White Paper

The government's plans for electricity market reform, published in July 2011, included three ways to encourage reducing carbon from electricity generation: a Carbon Price Floor, Feed-in tariffs (which would replace the Renewables Obligation), and an Emissions Performance Standard. These aimed to attract investment in low-carbon energy, ensure reliable supply, and keep consumer bills affordable.

Feed-in Tariff

A Feed-in tariff (FIT) provides a fixed income for a low-carbon power generator over a set time. The government preferred a FIT with a contract for difference (CfD), where a payment is made to ensure the generator receives an agreed price for their electricity. This was seen as the most cost-effective way to support low-carbon energy while still encouraging efficient market behavior.

FITs with CfDs were planned to replace the Renewables Obligation (RO) in 2017, after running alongside it from 2013. The RO gave certificates to renewable energy generators, which they could sell to suppliers. While the RO helped established renewables like wind power, it was less successful for newer technologies. It also didn't apply to nuclear generation.

The RO was criticized for uncertain certificate prices and being difficult for small generators. Reforms were made, like "banding" to give more support to less developed technologies. The introduction of FITs aimed to reduce risks for investors and lower the cost of delivering low-carbon electricity.

Emissions Performance Standard

An Emissions Performance Standard (EPS) limits how much carbon dioxide new power stations can emit per unit of electricity. This is needed if other market incentives aren't enough to move the electricity sector away from the most carbon-intensive ways of generating power. The EPS is set to balance decarbonization goals with keeping electricity affordable. It aims to prevent new coal-fired power stations from being built without carbon capture and storage technology.

Energy Bill, 2012–2013

The Energy Bill 2012–2013 aimed to close several coal power stations over the next two decades and reduce reliance on fossil fuels. It also provided financial incentives to reduce energy demand. The bill helped the construction of new nuclear power stations and set up a new Office for Nuclear Regulation. Government climate change targets were to produce 30% of electricity from renewable sources by 2020, cut greenhouse gas emissions by 50% by 2025 (compared to 1990 levels), and by 80% by 2050.

Select Committee Report, 2016

The Energy and Climate Change Select Committee reported in October 2016 on future energy and climate policy challenges. The committee suggested investing in energy storage and efficiency technologies to manage demand peaks.

Salix Finance Ltd.

Salix Finance Ltd. is a government-owned organization that provides funding to public sector bodies. Its goal is to help them improve energy efficiency, reduce carbon emissions, and lower energy bills.

Energy White Paper, 2020

The 2020 energy white paper set a target to achieve net zero in the UK by 2050 to stop climate change. The UK government aimed to do this by:

- Investing heavily in renewable energy, with a goal of 40 GW of offshore wind by 2030 (about 60% of the UK's energy use).

- Getting one large nuclear project to a final investment decision.

- Increasing the installation of electric heat pumps.

- Supporting carbon capture and storage.

- Creating a new UK emissions system.

- Discussing ending gas grid connections for new homes.

The government also launched the "Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution." Prime Minister Boris Johnson said it would "mobilise £12 billion of government investment" and potentially three times as much from the private sector. This plan aimed to create up to 250,000 green jobs and make the UK a leader in green technology and finance. It included support for electric cars, energy efficiency, nuclear power, hydrogen power, and carbon capture.

Government Oversight of Energy

Government supervision of the coal, gas, and electricity industries began in the 1800s. Since then, different government departments and regulatory bodies have been responsible for energy policy and control.

History of Oversight

In the 1800s, private companies and local councils mostly supplied energy (coal, gas, electricity). Local authorities controlled prices and encouraged competition. The government also passed laws like the Mines and Collieries Act 1842 and the Electric Lighting Act 1882 to oversee these industries. Early oversight came from the Board of Trade and the Home Office.

New Government Bodies

Between 1919 and 1941, the Ministry of Transport took control of the electricity industry. During World War II, the Ministry of Fuel and Power was created in 1942 to manage energy supplies. UK energy policy has been handled by many different ministries and departments over the years.

| Regulatory body | Established | Abolished / status | Political party | Tenure from | Tenure to | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Board of Trade | – | Continued | Various | c. 1847 | 1942 | Gas and electricity industries |

| Home Office | – | Continued | Various | 1842 | 1920 | Coal industry |

| Ministry of Transport | 1919 | Continued | Various | 1919 | 1941 | Electricity supply only |

| Board of Trade (Secretary for Mines) | 1920 | 1942 transferred to Ministry of Fuel and Power, Board of Trade continued | Various | 1920 | 1942 | |

| Board of Trade (Secretary for Petroleum) | 1940 | 1942 transferred to Ministry of Fuel and Power, Board of Trade continued | National | 1940 | 1942 | |

| Board of Trade | – | October 1970 became DTI | National | 1941 | 1942 | |

| Ministry of Fuel and Power | 3 June 1942 | 13 January 1957 renamed Ministry of Power | National | June 1942 | July 1945 | |

| Labour | August 1945 | October 1951 | ||||

| Conservative | October 1951 | January 1957 | ||||

| Ministry of Power | 13 January 1957 | 6 October 1969 merged with Ministry of Technology | Conservative | January 1957 | October 1964 | |

| Labour | October 1964 | October 1969 | ||||

| Ministry of Technology (MinTech) | 18 October 1964 | 15 October 1970 | Labour | October 1969 | June 1970 | |

| Conservative | June 1970 | October 1970 | ||||

| Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) | 15 October 1970 | January 1974 transferred to DoE, DTI continued | Conservative | October 1970 | January 1974 | |

| Department of Energy | 8 January 1974 | 11 April 1992 | Conservative | January 1974 | March 1974 | |

| Labour | March 1974 | 4 May 1979 | ||||

| Conservative | May 1979 | April 1992 | ||||

| Department of Trade and Industry | (11 April 1992) | June 2007 transferred to BERR, DTI continued | Conservative | April 1992 | May 1997 | |

| Labour | May 1997 | June 2007 | ||||

| Department of Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform | 28 June 2007 | October 2008 transferred to DECC 2008, BERR continued | Labour | June 2007 | October 2008 | |

| Department of Energy and Climate Change | 3 October 2008 | 14 July 2016 | Labour | October 2008 | May 2010 | |

| Coalition | May 2010 | May 2015 | ||||

| Conservative | May 2015 | July 2016 | ||||

| Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy | 14 July 2016 | current | Conservative | July 2016 | February 2023 | |

| Department for Energy Security and Net Zero | 7 February 2023 | current | Conservative | February 2023 | current |

Other Energy Regulators

Besides government ministries, several other bodies have been set up to regulate specific parts of energy policy:

- HM Inspectorate of Mines (since 1842)

- Electricity Commissioners (1919–1948)

- Central Electricity Board (1926–1948)

- National Coal Board (1947–1987)

- British Electricity Authority (1948–1955)

- Gas Council (1948–1973)

- Office of Electricity Regulation (Offer) (1990–2000)

- Office of Gas Supply (Ofgas) (1986–2000)

- Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem) (since 2000)

- Gas and Electricity Markets Authority (GEMA) (since 2000)

- Offshore Regulator for Environment and Decommissioning (OPRED)

- Oil and Gas Authority (since 2015)

Support for Fossil Fuels

In March 2014, David Cameron announced subsidies for the North Sea oil and gas industry. This was expected to lead to the production of 3-4 billion more barrels of oil than would have been produced otherwise.

Renewable Energy Targets

The first targets for renewable energy were set in 2000: 5% by the end of 2003 and 10% by 2010 (if costs were acceptable to consumers). The target was increased to 15% by 2015, and then to 20% by 2020 in the 2006 Energy Review.

The Low Carbon Transition Plan of 2009 clarified that by 2020, the UK needed to produce 30% of its electricity, 12% of its heat, and 10% of its transport fuels from renewable sources. For Scotland, the Scottish Government aimed to generate 100% of its electricity from renewables by 2020. Renewables in Scotland count towards both Scottish and UK targets.

While renewable energy hasn't always been a big part of the UK's energy mix, there's a lot of potential for tidal power and wind energy (both on-shore and off-shore). The Renewables Obligation is the main way the UK supports renewable electricity, providing large subsidies. Other grants also help less established renewables. Renewables are also exempt from the Climate Change Levy that affects other energy sources.

In 2004, 250 megawatts of renewable generation were added, and 500 megawatts in 2005. There's also a program for micro-generation (small-scale energy production from low-carbon sources) and a solar voltaic program. Countries like Germany and Japan have much larger solar cell programs than the UK. Hydroelectric energy isn't a good option for most of the UK due to its flat terrain and lack of strong rivers.

Biofuels

The government set a goal for five percent of total transport fuel to come from renewable sources (like ethanol or biofuel) by 2010, under the Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation. This goal was ambitious without the right infrastructure or research on UK crops. Importing from France was a more realistic option.

In 2005, British Sugar announced it would build the UK's first ethanol biofuel plant in Norfolk, using British-grown sugar beet. It was expected to produce 55,000 metric tonnes of ethanol annually by early 2007. Some argued that even using all of the UK's set-aside land for biofuel crops would provide less than 7% of the UK's transport fuel needs.

Fuel Poverty

One of the UK's main energy policy goals is to reduce fuel poverty. This is defined as households spending over 10% of their income on heating costs. Good progress has been made, mainly due to government subsidies to low-income families. Programs like Winter Fuel Payment, Child Tax Credit, and Pension Credit have been very helpful. Schemes like Warm Front in England, the Central Heating Programme in Scotland, and the Home Energy Efficiency Scheme in Wales have also provided money to improve insulation and other home features.

Oil and Gas

Oil and gas production in the UK reached its highest point in 1999. However, in 2023, the government approved more oil and gas exploration.

Images for kids

See also

- UK only

- United Kingdom National Renewable Energy Action Plan, 2009

- Campaign to Electrify Britain’s Railways

- Climate change in the United Kingdom

- Energy efficiency in British housing

- Electricity sector in the United Kingdom

- Energy switching services in the UK

- List of renewable resources produced and traded by the United Kingdom

- Merton Rule

- Timeline of the UK electricity supply industry

- UK Energy Research Centre

- UK enterprise law

- UK and beyond

- Avoiding dangerous climate change

- Energy policy of the European Union

- Energy policy of the United States

- Energy Saving Trust

- Financial incentives for photovoltaics

- Low Carbon Building Programme

- National Energy Action (NEA)

- The Carbon Trust

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |