Glyptodon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Glyptodon |

|

|---|---|

|

|

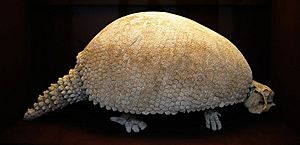

| Fossil specimen at the Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna | |

| Scientific classification |

Glyptodon was a huge, ancient mammal that lived a long time ago. It was like a giant armadillo! These amazing creatures had a tough, bony shell that covered their bodies. They lived in South America and were plant-eaters.

Glyptodon belongs to a group of mammals called Xenarthra. This group also includes animals you might know, like anteaters, tree sloths, and armadillos. There were also extinct relatives like ground sloths.

A close relative of Glyptodon, called Glyptotherium, moved into what is now the southern United States. This happened about 2.5 million years ago. It was part of a big animal migration called the Great American Interchange.

Contents

Where Glyptodon Lived

Glyptodon first appeared in South America. Their fossil remains have been found in countries like Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina.

They lived in different kinds of places. Some preferred forests or areas with some trees. Others lived in warm, humid places. Some even adapted to open, cold areas with lots of grasslands.

During the Great American Interchange, many animals moved between North America and South America. This happened when a land bridge, the Isthmus of Panama, formed. Glyptodon traveled north into Central America, reaching as far as Guatemala.

What Glyptodon Ate

Glyptodon were herbivores, meaning they ate plants. They mostly grazed on plants close to the ground. This was because of their body shape and stiff necks.

Scientists can tell what they ate by looking at their teeth and bones. Their diet included both dicotyledonous trees and monocotyledonous grasses. They often grazed near water sources like rivers and lakes.

Like many other xenarthrans, Glyptodon didn't need as much energy as other large mammals. This meant they could survive on less food than other plant-eaters of their size.

Glyptodon Behavior

Scientists believe that Glyptodon might have fought with each other. They think the tail was used as a weapon. The tail was very strong and flexible, with bony plates.

While the tail could protect them from predators, it seems it was mostly used for fights with other Glyptodon. They probably fought over land or to find a mate. This is similar to how male deer use their antlers to fight.

Glyptodon Body and Armor

Glyptodon was a very large animal. It could be about 3.3 meters (11 feet) long and 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall. It weighed up to 2,000 kilograms (4,400 pounds), which is as heavy as a small car!

Head

The nose area of Glyptodon was quite small. It had strong muscles attached to it for a reason we don't fully understand. Some scientists think they might have had a short proboscis, or trunk, like a tapir.

Their lower jaws were very deep. This helped support strong chewing muscles. These muscles were needed to chew tough, fibrous plants. Their teeth looked a bit like an armadillo's, but they had deep grooves on the sides.

Body Shell

The most amazing part of Glyptodon was its shell. It was made of over 1,000 bony plates called osteoderms or scutes. Each plate was about 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) thick.

Every type of Glyptodon had a unique pattern on its shell. This armor made them very well protected, almost like a turtle. But unlike most turtles, Glyptodon couldn't pull its head into its shell. Instead, it had a thick, bony cap on its skull. Even its tail had bony rings for protection.

This heavy shell needed a lot of support. Glyptodon had strong, fused vertebrae (backbones). They also had short, powerful legs and strong shoulder bones.

Tail

The tail of Glyptodon clavipes, a specific type of Glyptodon, was covered in free bony rings. This made it strong, flexible, and easy to move. They could swing their tails with great power.

As mentioned before, these tails were likely used in fights. They might also have been used to attract mates.

Predators and Extinction

Glyptodon was so big and well-armored that not many animals could hunt it. However, some large predators might have tried. These could include saber-toothed cats like Smilodon and Homotherium. Giant short-faced bears called Arctotherium and dire wolves might also have been a threat.

There is some evidence that early humans hunted Glyptodon. Scientists have found a few Glyptodon bones with signs that humans ate them. It's also thought that hunters might have used the empty shells of dead Glyptodon as shelters during bad weather.

Many scientists believe that humans played a part in the extinction of Glyptodon.

Images for kids

-

Richard Owen's 1839 reconstruction of a Glyptodon skeleton; teeth at right

See also

In Spanish: Glyptodon para niños

In Spanish: Glyptodon para niños