Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna Romanova |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Photo, c. 1914

|

|||||

| Born | 18 June [O.S. 5 June] 1901 Peterhof Palace, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

||||

| Died | 17 July 1918 (aged 17) Ipatiev House, Yekaterinburg, Russian Soviet Republic |

||||

| Burial | 17 July 1998 Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation |

||||

|

|||||

| House | Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov | ||||

| Father | Nicholas II of Russia | ||||

| Mother | Alix of Hesse | ||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodox | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia (Russian: Анастасия Николаевна Романова, romanized: Anastasiya Nikolaevna Romanova; 18 June [O.S. 5 June] 1901 – 17 July 1918) was the youngest daughter of Tsar Nicholas II. He was the last ruler of Imperial Russia. Her mother was Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna.

Anastasia had three older sisters: Olga, Tatiana, and Maria. She also had a younger brother, Alexei. Anastasia and her family were killed by a group of revolutionaries called Bolsheviks in Yekaterinburg on July 17, 1918.

For many years, people wondered if Anastasia had somehow survived. This was because her burial place was a secret during the time of Communist rule in Russia. In 1991, a mass grave was found near Yekaterinburg. It held the remains of the Tsar, his wife, and three of their daughters. These remains were buried in 1998. The bodies of Alexei and the remaining daughter (either Anastasia or Maria) were found in 2007. Scientists used DNA testing to confirm that all four grand duchesses were killed in 1918. This proved that Anastasia did not survive.

Several women falsely claimed to be Anastasia. The most famous was Anna Anderson. DNA tests on her remains in 1994 showed she was not related to the Romanov family.

Contents

Discovering Grand Duchess Anastasia's Life

Her Early Life and Family

Anastasia was born on June 18, 1901. She was the fourth daughter of Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra. Her parents and family had hoped for a son to inherit the throne. So, they were a bit disappointed when Anastasia was born. Her aunt, Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna of Russia, even said, "My God! What a disappointment!... a fourth girl!"

Anastasia was named after St. Anastasia, a Christian martyr. Her name means "of the resurrection," which later added to the rumors of her survival. Her proper title was "Grand Princess," but "Grand Duchess" became the common English translation.

The Tsar's children were raised simply. They slept on hard beds without pillows, unless they were sick. They took cold baths each morning. They were also expected to clean their rooms and do needlework for charity. Most people in the household called her "Anastasia Nikolaevna." Her family also had nicknames for her, like "Malenkaya" (meaning "little one") or "Shvybzik" (meaning "merry little one" or "little mischief").

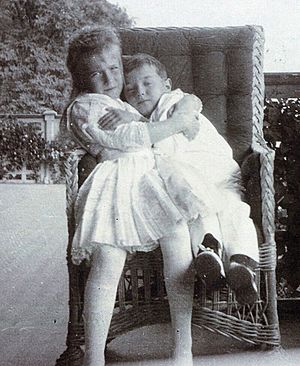

Anastasia and her older sister Maria were known as "The Little Pair." They shared a room and often wore similar clothes. Their older sisters, Olga and Tatiana, were "The Big Pair." The four sisters sometimes signed letters using "OTMA," which came from the first letter of each of their names.

DNA tests later showed that Anastasia's younger brother, Alexei, had Hemophilia B. This is a rare blood disorder. His mother and one sister (either Maria or Anastasia) were carriers of the gene. This meant they could pass the disease on, even if they didn't have it themselves.

Her Appearance and Personality

Anastasia was short and tended to be a bit chubby. She had blue eyes and blonde hair. Her mother's lady-in-waiting, Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden, said Anastasia had "fine eyes, with impish laughter in their depths." She thought Anastasia looked more like her mother's family.

Anastasia was a lively and energetic child. Her governess, Margaretta Eagar, said Anastasia had great personal charm even as a toddler.

Her teachers, Pierre Gilliard and Sydney Gibbes, said she was bright but not interested in school rules. They, along with others, described Anastasia as lively, mischievous, and a talented actress. She often made sharp, witty remarks.

Anastasia was sometimes very daring. Gleb Botkin, whose father was the court doctor, said she was a "true genius" at being naughty. She would sometimes trip servants or play tricks on her teachers. As a child, she would climb trees and refuse to come down. Once, during a snowball fight, she put a rock in a snowball and threw it at her older sister Tatiana, knocking her down. A distant cousin, Princess Nina Georgievna, even said Anastasia could be "nasty to the point of being evil." She cared less about her looks than her sisters.

Despite her energy, Anastasia sometimes had health problems. She suffered from painful bunions on her big toes. She also had a weak back muscle and needed massages twice a week. She would sometimes hide to avoid them!

Her Connection with Grigori Rasputin

Anastasia's mother, the Tsarina, trusted Grigori Rasputin. He was a Russian peasant and a "holy man." She believed his prayers helped her son Alexei, who was often sick. Anastasia and her siblings were taught to see Rasputin as "Our Friend." They shared their secrets with him. In 1907, Anastasia's aunt, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia, met Rasputin in the nursery. Olga Alexandrovna remembered, "All the children seemed to like him. They were completely at ease with him."

Rasputin often sent messages to the imperial children. In 1909, he advised them to "Love the whole of God's nature." The imperial family's friendship with Rasputin continued until he was murdered in December 1916.

Rasputin was buried with an icon signed by Anastasia, her mother, and her sisters. She attended his funeral. After the family was killed, it was found that Anastasia and her sisters were wearing amulets with Rasputin's picture and a prayer.

World War I and the Russian Revolution

During World War I, Anastasia and her sister Maria visited wounded soldiers. They went to a hospital on the grounds of Tsarskoye Selo. The two teenagers were too young to be Red Cross nurses like their mother and older sisters. Instead, they played games like checkers and billiards with the soldiers to cheer them up. Felix Dassel, a soldier she met, said Anastasia had a "laugh like a squirrel."

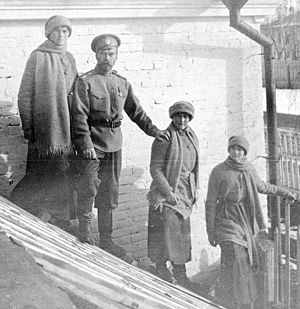

In February 1917, Anastasia and her family were put under house arrest at the Alexander Palace during the Russian Revolution. Her father, Nicholas II, gave up his throne. As the Bolsheviks gained power, the family was moved to Tobolsk, Siberia. Later, they were moved to the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg.

The stress of being held captive affected Anastasia and her family. "Goodby," she wrote to a friend in 1917. "Don't forget us."

Even in her last months, Anastasia found ways to have fun. She and others performed plays for her parents in the spring of 1918. Her tutor, Sydney Gibbes, said Anastasia's acting made everyone laugh.

One of the guards at the Ipatiev House, Alexander Strekotin, remembered Anastasia as "very friendly and full of fun." Another guard said she was "a very charming devil! She was mischievous and, I think, rarely tired." She was lively and enjoyed doing funny mimes with the dogs. However, another guard called her "offensive and a terrorist" because her comments sometimes caused problems. Anastasia and her sisters helped their maid mend stockings and helped the cook with baking.

In the summer, their captivity became harder. On July 14, 1918, priests held a church service for the family. They noticed that Anastasia and her family knelt during a prayer for the dead, which was unusual. The girls seemed sad and hopeless, and they no longer sang along. One priest thought, "Something has happened to them in there." But the next day, Anastasia and her sisters seemed in good spirits. They joked and helped move beds for cleaning. Anastasia even stuck her tongue out at Yakov Yurovsky, the head guard, when he turned his back.

Captivity and Death

After the Bolshevik revolution in October 1917, Russia fell into civil war. Talks to free the Romanovs failed. As anti-Bolshevik forces (called 'Whites') moved toward Yekaterinburg, the Bolsheviks (called 'Reds') were in danger. The Reds knew Yekaterinburg would fall to the White Army. When the Whites arrived, the imperial family had vanished. Most people believed the family had been murdered. This was supported by an investigation that found items belonging to the family in a mine shaft.

A document called the "Yurovsky Note," written by the head guard Yurovsky, was found in 1989. It described the events of the killings. On the night of July 17, 1918, the family was woken up and told to get dressed. They were told they were moving to a safer place. Once dressed, the family and their few remaining servants were led into a small basement room. Alexandra and Alexei sat in chairs.

After a few minutes, the guards entered, led by Yurovsky. He quickly told the Tsar and his family that they would be executed. The Tsar only had time to say "What?" and turn to his family before the guards started shooting.

The Mystery of Anastasia's Survival

Anastasia's supposed escape was a famous mystery in the 20th century. Many books and films were made about it. At least ten women claimed to be her. The most well-known was Anna Anderson. She appeared publicly between 1920 and 1922. She claimed she pretended to be dead among the bodies and escaped with the help of a kind guard. Her legal fight to be recognized lasted for many years. However, the court decided she had not proven her claim.

Anna Anderson died in 1984. In 1994, DNA tests were done on her tissue and hair. The tests showed she was not related to the Romanov family. Her DNA matched a relative of a missing Polish factory worker named Franziska Schanzkowska. This proved that Anna Anderson was not Grand Duchess Anastasia.

Other women also claimed to be Anastasia, like Nadezhda Ivanovna Vasilyeva and Eugenia Smith. Two young women claiming to be Anastasia and her sister Maria lived as nuns in the Ural Mountains until their deaths in 1964. They were buried under the names Anastasia and Maria Nikolaevna.

Rumors of Anastasia's survival grew because Bolshevik soldiers sometimes searched for "Anastasia Romanov." In 1918, Princess Helena Petrovna was in prison in Perm. She said a guard brought a girl who called herself Anastasia Romanova to her cell. The guard asked if the girl was the Tsar's daughter. Helena Petrovna said she did not recognize the girl. This story is now largely believed to be false. The rumors were also fueled by false information. The German government asked about the safety of the "princesses of German blood." Russia had just signed a peace treaty with Germany and did not want to upset them. So, they said the women had been moved to a safer place, hiding the truth of their deaths.

In another event, eight people said they saw a young woman recaptured after an escape attempt in September 1918. Some of these witnesses identified the girl as Anastasia from photographs. A doctor who treated the injured girl said she told him, "I am the daughter of the ruler, Anastasia." However, during this time, many young people in Russia pretended to be Romanov escapees.

Finding the Romanov Graves and DNA Proof

In 1991, the believed burial site of the imperial family and their servants was found near Yekaterinburg. The grave had been discovered earlier but kept secret from the Communists. This grave held nine bodies, not the expected eleven. DNA and bone analysis matched these remains to Tsar Nicholas II, Tsarina Alexandra, and three of their four grand duchesses (Olga, Tatiana, and likely Maria). The other remains belonged to the family's doctor, valet, cook, and Alexandra's maid.

On August 23, 2007, a Russian archaeologist announced the discovery of two more partial skeletons. They were found at a bonfire site near Yekaterinburg, matching descriptions in Yurovsky's notes.

DNA testing by several international labs confirmed that these remains belonged to Tsarevich Alexei and one of his sisters. This proved that all family members, including Anastasia, died in 1918. The parents and all five children are now accounted for, each with their own unique DNA profile.

Sainthood

| Saint Anastasia Romanova | |

|---|---|

| Saint, Grand Duchess and Passion bearer | |

| Honored in | Russian Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | 1981 and 2000 by Russian Orthodox Church Abroad and the Russian Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Church on Blood, Yekaterinburg, Russia |

| Feast | 17 July |

In 2000, Anastasia and her family were made saints by the Russian Orthodox Church. They are called passion bearers, meaning they faced suffering in a Christ-like way. The family had already been made saints in 1981 by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. The bodies of Tsar Nicholas II, Tsarina Alexandra, and three of their daughters were buried in the Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral on July 17, 1998. This was eighty years after they were murdered. As of 2018, the bones of Alexei and Maria (or possibly Anastasia) were still held by the Orthodox Church.

Anastasia in Movies and Books

The idea that Anastasia survived has been the subject of many movies and books. These include the 1997 animated film and the 1956 film starring Ingrid Bergman. There was also a Broadway musical. The earliest film, made in 1928, was called Clothes Make the Woman. It told the story of a woman who played Anastasia in a movie and was then recognized by a soldier who supposedly rescued her.

See also

In Spanish: Anastasia Nikoláyevna de Rusia para niños

In Spanish: Anastasia Nikoláyevna de Rusia para niños