Hayden Geological Survey of 1871 facts for kids

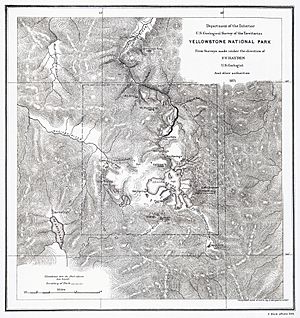

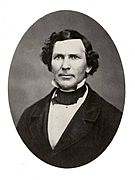

The Hayden Geological Survey of 1871 was an important trip that explored the northwestern part of Wyoming. This area later became Yellowstone National Park in 1872. Geologist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden led this survey.

While Hayden had led other surveys, the 1871 trip was special. It was the first time the U.S. government paid for a detailed exploration of the Yellowstone region. This survey played a huge role in convincing the U.S. Congress to create Yellowstone National Park.

In 1894, Nathaniel P. Langford, who was the first park superintendent and part of an earlier expedition, wrote about the Hayden trip:

We trace the creation of the park from the Folsom-Cook expedition of 1869 to the Washburn expedition of 1870, and thence to the Hayden expedition (U. S. Geological Survey) of 1871, Not to one of these expeditions more than to another do we owe the legislation which set apart this "pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people"

—Nathaniel P. Langford

Contents

Why the Survey Happened

The 1871 Hayden survey was part of a bigger plan. In 1853, Congress passed a bill to find the best routes for railroads across the U.S. This led to an era of "Great Surveys" after the Civil War. These surveys brought together explorers, engineers, scientists, and mapmakers to chart the western U.S. Hayden, along with John Wesley Powell, Clarence King, and George Wheeler, were key leaders of these surveys.

In March 1871, Congress gave $40,000 to fund Hayden's fifth survey. This trip was mainly to explore Idaho and Montana. Hayden knew that Jay Cooke wanted to promote the Yellowstone area for the Northern Pacific Railroad. He had also heard Nathaniel P. Langford's lecture about the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition to Yellowstone from the year before.

Even though the money wasn't available until July 1, Hayden was determined. He organized his team with help from the U.S. Army, Fort Bridger, and the railroads. The Army let him use equipment and supplies from frontier posts. Also, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads agreed to transport his men and gear for free.

Hayden had a very experienced assistant named James Stevenson. Stevenson had worked with Hayden since 1866. He helped Hayden with every project until their survey joined with others to form the U.S. Geological Survey in 1879.

Hayden and Stevenson prepared the survey members at Fort D. A. Russell in Wyoming. They then transported their equipment, food, wagons, and animals by train to Ogden, Utah. A base camp was set up there in May. In the spring of 1871, Hayden chose 32 team members. These included friends, colleagues, and people who had been on his previous surveys.

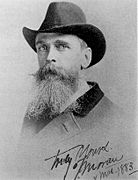

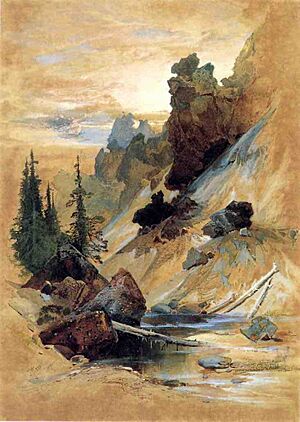

Important members included William Henry Jackson, his photographer from the 1870 survey. Also, Thomas Moran, a famous artist, joined as a guest. Two younger members were Albert Peale, a mineralogist, and George Allen, a botanist. Both Allen and Peale kept journals that later gave great details about the survey's daily life.

The Survey's Journey

The survey officially started on June 8, 1871, from Ogden, Utah 41°13′40″N 111°57′40″W / 41.227744°N 111.961193°W. However, many members had already started collecting things in Salt Lake City and Ogden. The team traveled north, reaching Taylor's Bridge 43°29′30″N 112°01′57″W / 43.491775°N 112.032509°W (now Idaho Falls) on the Snake River by June 25. By June 30, they were in Montana, camping near Monida Pass 44°33′31″N 112°18′20″W / 44.55861°N 112.30556°W.

Hayden's group reached Virginia City, Montana 45°17′39″N 111°56′28″W / 45.294107°N 111.94123°W on July 4. They arrived at Fort Ellis near Bozeman, Montana on July 10. Here, Thomas Moran, the artist, joined them. George Allen, the botanist, and Cyrus Thomas, the entomologist, left due to health reasons. A guide named José joined the team.

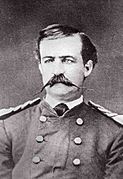

After getting more supplies at Fort Ellis, the survey headed south along the Yellowstone River on July 15. For the next 45 days, the Hayden Survey worked with the Barlow-Heap expedition. This was a U.S. Army group led by Colonel John W. Barlow that was also exploring Yellowstone.

As the team went up the Yellowstone River in what is now Paradise Valley, they realized their wagons couldn't handle the trail. Near Bottler's Ranch 45°19′30″N 110°47′33″W / 45.32500°N 110.79250°W, they set up a base camp. This camp helped with communication and supplies from Fort Ellis. Leaving their wagons, the survey entered Yankee Jim Canyon 45°11′43″N 110°54′05″W / 45.19528°N 110.90139°W on July 20.

Exploring Yellowstone's Wonders

On July 21, 1871, the Hayden survey entered the Yellowstone park area. They went up the Gardner River to what is now Mammoth Hot Springs. They explored and camped there for two days. At Mammoth, they found two men who had claimed land and set up a ranch and bath house. These men later built a simple hotel.

On July 24, the team left Mammoth for Tower Fall. They followed a route similar to today's Mammoth-Tower road. They passed Undine Falls 44°56′39″N 110°38′20″W / 44.94417°N 110.63889°W and Wraith Falls 44°56′14″N 110°37′25″W / 44.93722°N 110.62361°W. They reached Tower Creek and camped there on July 25.

The survey team spent three days traveling around Mount Washburn. They also went along the western edge of the Yellowstone River in Hayden Valley. They reached Yellowstone Lake on July 28. Here, Lt. Gustavus C. Doane took over as commander of the military escort.

Near Yellowstone Falls, W. H. Jackson took the first known photographs of the falls. On July 28, some members built a small boat called Annie. It was the first known boat to sail on Yellowstone Lake. Annie was used to explore the islands and measure the lake's depth. James Stevenson and Henry Elliot made the first trip to an island, which Hayden named Stevenson Island 44°30′55″N 110°23′07″W / 44.51528°N 110.38528°W.

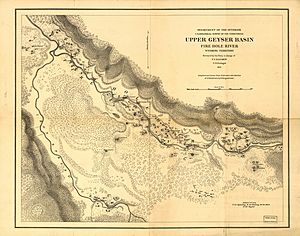

On July 31, Hayden and some of his team left Yellowstone Lake. They went back into Hayden Valley to the Crater Hills Geyser group. From there, they headed west to the geyser basins of the Madison River. They reached Nez Percé Creek 44°34′40″N 110°37′13″W / 44.57778°N 110.62028°W and camped near the Firehole River. The group spent several days exploring the Lower, Midway, and Upper Geyser basins before leaving on August 6.

The survey followed the Firehole River upstream to Madison Lake 44°20′55″N 110°51′58″W / 44.34861°N 110.86611°W. Then they crossed a divide to Shoshone Lake. They camped near Lost Lake, about 6 miles (10 km) from the West Thumb area of Yellowstone Lake. On August 7, they explored West Thumb for two days. They sent letters and collected specimens back to the base camp at Bottler's Ranch with the military escort. Hayden's report to Dr. Spencer Fullerton Baird of the Smithsonian Institution was among these.

Between August 9 and August 19, the survey team traveled around the southern and eastern sides of Yellowstone Lake. They crossed the Continental Divide twice. They also explored where the Yellowstone River begins. On August 19, they reached Steamboat Point 44°31′54″N 110°17′34″W / 44.53167°N 110.29278°W on the northeast side of the lake. Hayden named it for nearby steam vents. They camped there to prepare for their return to the Yellowstone River via the East Fork (Lamar River). While at Steamboat Point, they felt two strong earthquakes.

On August 23, after taking apart and hiding the boat Annie, the group moved northeast from Yellowstone Lake. They followed Pelican Creek to Mirror Lake 44°44′05″N 110°09′51″W / 44.73472°N 110.16417°W, where they camped. The next morning, they continued northeast to the start of the East Fork of the Yellowstone River (Lamar River). They followed the river downstream. On August 25, they entered the upper Lamar Valley and traveled northwest to the Yellowstone River at Baronette Bridge 44°55′45″N 110°24′03″W / 44.92917°N 110.40083°W. This was the first bridge across the Yellowstone. By August 26, most of the survey party had left the park area. They camped north of Gardiner on the Yellowstone River. The next day, most met at Bottler's Ranch.

Journey Back Home

After leaving Bottler's Ranch, the group took two days to reach Fort Ellis. They stayed there for six days to rest, get new supplies, and prepare letters and specimens for shipping. Three members left for California. During this time, Hayden wrote to George Allen, his former professor who had left the survey earlier.

On September 5, the remaining members of Hayden's group left Fort Ellis. They headed to Three Forks, Montana, and the Jefferson River valley. They followed the Jefferson River to the Beaverhead River. They camped at Beaverhead Rock 45°23′11″N 112°27′35″W / 45.38639°N 112.45972°W on September 9. Jackson took the first photographs of this rock.

They continued south, crossing a divide near Red Rock River. By September 14, they were camped on Medicine Lodge Creek in Idaho. They followed Medicine Lodge Creek to the Snake River plain, arriving at Fort Hall on September 18. Hayden wrote another report to Spencer Baird from Fort Hall.

By September 29, the survey party reached Evanston, Wyoming Territory. They took a train to Fort Bridger, arriving on October 2. At Fort Bridger, Hayden officially ended the survey. Hayden and Peale went to Salt Lake City and then back to Washington, D.C. Jackson and Charlie Turnbull traveled to Nebraska to photograph Pawnee Indians.

How the Survey Worked

Once the survey team was ready, James Stevenson, the survey manager, and Stephan Hovey, the wagonmaster, decided the general route and camping spots. In open areas, like northern Utah, the team traveled about 15 miles (24 km) per day. After several days of travel, they would camp for a few days to rest, process their findings, and get more supplies.

While traveling and camping, scientists, photographers, and mapmakers would go out in small groups. They collected specimens, made observations, and documented the plants, animals, geology, and geography of the land. Hayden himself was just another scientist doing this work. Hunters also tried to find enough game to feed the group.

In camp, the scientists processed and documented their findings. They prepared them for shipment to the Smithsonian Institution as soon as possible. Plant samples were pressed, dried, and labeled. Mineral samples were trimmed, labeled, and packaged. Photographs were cataloged and described. Letters were written to scientists back East, explaining their discoveries and progress. When the team found a place that could handle mail or shipments, like a town or Army post, they sent their materials East.

George Allen, the botanist, described a typical day in his journal:

Thursday, June 29 [1871] - After the Camp broke up went with the Photographic corps on a hill overlooking the vale and changed the papers of the pressed plants, while Jackson took pictures ... The hills in this passway to Montana are all of igneous character; but there are other varieties of rock boulders (principally quartzites) indicating a different character to the higher mountain passes around. ... After 12 miles traveled today in which we were rapidly ascending we came to the summit of the Chain—the Divide (Monida Pass). ... At our camp the P.M. five miles from the divide, we have excellent grass and water, and it is understood that we will remain over here one day to recruit. Collected and pressed a large amount of plants. Also found in the streams a number of shells--lymneas and physas. Junction stage station is near our camp.

Survey Team and Gear

| Members | Equipment and transport |

|---|---|

|

|

- Members of the survey

How the Expedition Helped Create a National Park

The Hayden expedition produced many important things. These included the amazing sketches and paintings by Thomas Moran and the photographs by William Jackson. But most importantly, Hayden wrote a long report detailing all his team's findings.

Hayden, working with Nathaniel Langford and Jay Cooke, really wanted to protect the Yellowstone region. He even included drawings and descriptions of hot springs from Langford's articles. Hayden showed his report, photos, sketches, and paintings to Senators, Congressmen, and anyone else who could help create a park.

His political connections were very helpful. Congressman Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts had supported funding the expedition. His son, Chester Dawes, was even a member of the survey team. The boat Annie on Yellowstone Lake was supposedly named after Dawes' daughter, Anna. Hayden also wrote articles for national magazines. He spent a lot of personal time trying to convince Congress to establish the park.

On December 18, 1871, a bill was introduced in both the Senate and the House of Representatives. It aimed to create a park at the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. Hayden's influence on Congress was clear. The House Committee on Public Lands report stated: "The bill now before Congress has for its objective the withdrawal from settlement, occupancy, or sale, under the laws of the United States a tract of land fifty-five by sixty-five miles, about the sources of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers, and dedicates and sets apart as a great national park or pleasure-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people."

When the bill was presented, its main supporters, prepared by Langford, Hayden, and Jay Cooke, convinced their colleagues. They argued that the region's true value was as a park, to be kept in its natural state. The Senate approved the bill easily on January 30, 1872. The House approved it on February 27.

On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the bill into law. This officially established the Yellowstone region as a public park. It was a result of three years of exploration by the Cook-Folsom-Peterson (1869), Washburn-Langford-Doane (1870), and Hayden (1871) expeditions.

Yellowstone Features Named After Survey Members

Many places in Yellowstone National Park are named to honor the people from the 1871 expedition:

- Carrington Island - named for E. Campbell Carrington

- Mount Doane - named for Lt. Gustavus C. Doane

- Frank Island - named for Henry Elliot's brother, Frank Elliot

- Hayden Valley - named for Ferdinand V. Hayden

- Moran Point - named for Thomas Moran

- Mount Jackson - named for William Henry Jackson

- Peale Island - named for Albert C. Peale

- Mount Stevenson - named for James Stevenson

- Stevenson Island - named for James Stevenson

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |