Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom und zum Stein facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom und zum Stein

|

|

|---|---|

| Reichsfreiherr | |

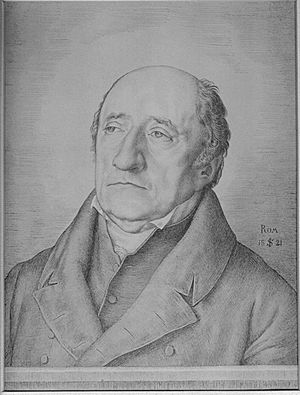

Heinrich Friedrich Karl Reichsfreiherr vom und zum Stein (painting by Johann Christoph Rincklake)

|

|

| Born | 25 October 1757 Nassau, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 29 June 1831 (aged 73) Cappenberg Castle, Province of Westphalia, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Occupation | Politician; Minister |

Heinrich Friedrich Karl Reichsfreiherr vom und zum Stein (born October 25, 1757 – died June 29, 1831), often called Baron vom Stein, was an important Prussian statesman. He introduced major changes known as the Prussian reforms. These reforms helped prepare the way for Germany to become one country later on.

Stein helped end serfdom, which was a system where peasants were tied to the land. He also made sure that noble landowners had to pay taxes, just like everyone else. He also created a modern system for towns to govern themselves.

Stein came from an old family in Franconia, a region in Germany. He was born on his family's estate near Nassau. He studied at the University of Göttingen and then started working for the government. At first, his ideas for change were held back by traditional ways in Prussia. In 1807, the King removed him from his job. But he was called back after the Peace of Tilsit, a treaty with France.

Later, it was discovered that Stein had written a letter criticizing Napoleon. Because of this, he had to resign on November 24, 1808. He moved to the Austrian Empire. In 1812, Tsar Alexander I of Russia invited him to Russia. After the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, Stein became the head of the group that managed the German lands taken back from France.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom und zum Stein was the ninth child in his family. His father was Karl Philipp Freiherr vom Stein. His mother was Henriette Karoline Langwerth von Simmern. Stein's father was a strict man, and Stein inherited some of his strong personality.

His family belonged to the group of imperial knights in the Holy Roman Empire. These knights were somewhat independent. They owned their own lands and answered only to the emperor. They were not subjects of other princes.

As he grew older, Stein often said he was thankful for his parents' strong values. He admired their religious beliefs and their German, knightly example.

English ideas were very popular in the 1700s, and they influenced Stein early in his life. He did not go to a regular school. In 1773, he went with a private teacher to the University of Göttingen in Hanover. There, he studied jurisprudence (the theory of law). He also spent time studying English history and politics. He later wrote that these studies made him like the English people even more.

Starting His Career

In 1777, Stein left Göttingen. He went to Wetzlar, which was a major legal center in the Holy Roman Empire. He wanted to learn how its laws and systems worked. After visiting several important cities in Southern Germany, he settled in Regensburg. Here, he observed the methods of the Imperial Diet, which was like a parliament. In 1779, he went to Vienna, and then to Berlin in early 1780.

In Berlin, Stein admired Frederick the Great, the Prussian king. He also disliked the slow legal process he had seen in Wetzlar. These feelings led him to join the Prussian government. He was lucky to get a job in the department of mines and manufacturing. The head of this office was a smart leader named Friedrich Anton von Heynitz. Heynitz helped Stein learn about economics and how to run a government.

In June 1785, Stein worked as a Prussian ambassador for a short time. He served in the courts of Mainz, Zweibrücken, and Darmstadt. But he soon realized he did not like diplomacy. In 1786 and 1787, he traveled in England. There, he continued his studies on trade and mining.

In November 1787, he became a Kammerdirektor. This meant he was a director of the war and domains chamber. He was in charge of the king's lands west of the Weser river. From 1796 to 1803, he was the main president for all the Westphalian chambers. These chambers managed trade and mines in those Prussian lands. Their main office was in Minden. One of his biggest achievements was making the Ruhr river suitable for boats. This helped transport coal from the region. He also improved navigation on the Weser river and kept the main roads in good condition.

Prussia and France

Stein's early training and practical nature made him cautious about the French Revolution. Many people in Germany were excited by it. But Stein disliked its methods, seeing them as a disruption to orderly progress. Still, he carefully noticed how France gained strength from its reforms.

Meanwhile, Prussia had fought France from 1792 to 1795. They made peace at Basel in April 1795. Prussia remained peaceful until 1806. But Austria and Southern Germany continued fighting France. Prussia actually became weaker during this time. Frederick William III became king in November 1797. He was not a strong leader. He often let secret advisors influence public matters. He continued a policy of being too friendly with France.

In 1804, Stein became the minister of state for trade in Berlin. This included taxes, manufacturing, and commerce. He made useful changes in his department. For example, he removed many rules that limited trade within the country. But he faced resistance from traditional Prussian ways. He soon protested against the pro-French policies of the chief minister, Christian Graf von Haugwitz. He also spoke out against bad influences in the government.

Stein's protests were strong and clear. But little changed. Prussian policy continued on a path that led to disaster at the Battle of Jena on October 14, 1806.

After the defeat, the king offered Stein the job of foreign affairs minister. Stein refused. He said he couldn't do that job unless the whole government system changed. He really wanted Karl August von Hardenberg to take that job. Stein hoped they could work together to make needed changes. The king refused Hardenberg. He was very annoyed by Stein's honest letters. So, he fired Stein completely. The king called him "a difficult, rude, stubborn, and disobedient official." Stein then spent time away from public life. During this time, Napoleon finished ruining Prussia.

In April 1807, Stein saw Hardenberg called to office. Important changes were made to the government system. During talks at Tilsit, Napoleon refused to work with Hardenberg. So Hardenberg retired. Strangely, Napoleon suggested Stein as a possible replacement. At this point, Napoleon didn't know how deeply patriotic Stein was. No other strong leader was available to save the country. So, on October 8, 1807, Frederick William called Stein back to office. The king was very sad about the harsh terms of the Treaty of Tilsit. He gave Stein a lot of power.

Stein was now almost like a dictator of the small, nearly bankrupt Prussian state. The situation and his own beliefs led him to push for big reforms.

First came the October Edict, issued at Memel on October 9, 1807. This law ended serfdom throughout Prussia by October 8, 1810. All differences in land ownership (like noble land or peasant land) were also removed. The idea of free trade in land was started right away. This famous law also ended all class differences for jobs and professions. This was another blow to the strict class system in Prussia. Stein then worked to make the government stronger with smart changes.

Stein also introduced a law for municipal reform on November 19, 1808. This law gave local self-government to all Prussian towns. It even included villages with more than 800 people.

While Stein focused on civil matters, he also supported military reforms. These reforms are often linked to Gerhard Johann David von Scharnhorst. They reshaped the Prussian army to be more modern. A reserve system was created. Military service became required for everyone, no matter their social class.

Life in Exile

Soon after his reforms, Stein had to leave Prussia. In August 1808, French spies found one of his letters. In it, he wrote that he hoped Germany would soon rise up like Spain. On September 10, Napoleon ordered that Stein's property in the new kingdom of Westphalia be taken. He also pressured Frederick William to fire Stein.

The king tried to avoid this. But the French emperor, after entering Madrid, declared Stein an enemy of France. He ordered all of Stein's property in the German Confederation to be taken. Stein knew his life was in danger. He fled from Berlin on January 5, 1809. With help from his friend, Count Friedrich Wilhelm von Reden, he found a safe place in his castle in the Riesengebirge mountains. From there, he managed to cross into Bohemia.

For three years, Stein lived in the Austrian Empire, mostly in Brno. But in May 1812, he was in danger of being handed over to Napoleon by Austria. So, he received an invitation to visit Saint Petersburg from Emperor Alexander I of Russia. Alexander knew that Austria would likely side with France in the upcoming Franco-Russian War. During this war, Stein might have been one of the people who convinced the Tsar never to make peace with Napoleon. When the defeated French army returned to Prussia at the end of the year, Stein urged the Russian emperor to continue fighting and free Europe from French control.

Events quickly brought Stein back into the spotlight. On December 30, 1812, the Prussian general Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg signed the Convention of Tauroggen. This agreement made the Prussian army neutral and allowed Russian troops to pass through Prussian lands. The Russian emperor asked Stein to manage the provinces of East and West Prussia temporarily. In this role, Stein called a meeting of local representatives. On February 5, 1813, this assembly ordered the creation of a militia (Landwehr), a militia reserve, and a final levy (Landsturm).

Stein's energy helped greatly in this important decision. It pushed the king's government to take stronger action. Stein then went to Breslau, where the King of Prussia had gone. But the king was annoyed by Stein's independent actions, which reduced his influence.

The Treaty of Kalisz between Russia and Prussia in 1813 was not directly due to Stein's actions. His ideas were seen as too extreme by some in the court. At that time, the great patriot fell ill with a fever. He felt neglected by the king and the court.

However, he recovered in time to help draft a Russian-Prussian agreement on March 19, 1813. This agreement was about managing the areas freed from French control. During the different stages of the 1813 campaign, Stein continued to push for an all-out war against Napoleon.

After England and Austria joined the alliance, the Allies gave Stein important duties. He was to oversee the management of the freed territories.

Stein wanted Germany to become one nation. But Austrian diplomat Prince Klemens Wenzel von Metternich stopped this. Metternich gained the support of rulers in southern and central Germany for his empire. They agreed to keep their old powers. Austria and the smaller German states resisted all ideas for unification. Stein blamed the Prussian chancellor Hardenberg for being indecisive.

Stein also wanted Prussia to take over Saxony. But he was disappointed in this too. On May 24, 1815, he sent a detailed critique of the proposed federal system for Germany to Emperor Alexander. He retired after the Congress of Vienna. He disliked that the representative government, which Frederick William had promised Prussia in May 1815, was delayed.

Later Life and Legacy

Stein's main interest in his later years was studying history. From 1818 to 1820, he worked hard to create a society for historical research. This society would publish the Monumenta Germaniae historica, a collection of historical documents. His future biographer, Georg Heinrich Pertz, became its director.

Stein died at Schloss Cappenberg in Westphalia on June 29, 1831. His burial place is in the city of Bad Ems near Koblenz.

Research shows that many of the important reforms of 1807-1808 were not just Stein's ideas. Others, like Theodor von Schön, also contributed. A popular story said he founded the Tugendbund, a secret society. But Stein always distrusted this group.

Stein's clear thinking, understanding of what was needed, and strong energy truly drove the reform movement forward.

Family Life

On June 8, 1793, Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom und zum Stein married Countess Wilhelmine Magdalene von Wallmoden. She was born on June 22, 1772, and died on September 15, 1819. Wilhelmine was the daughter of Johann Ludwig von Wallmoden-Gimborn. He was an illegitimate son of King George II of Great Britain. Stein and Wilhelmine had three daughters. One of them was Henriette Luise (born August 2, 1796 – died October 11, 1855).

Images for kids

-

The town of Nassau with the castle and family home of the imperial knights of Stein (copper engraving by Matthäus Merian 1655)

-

Statue of von Stein at the town hall in Wetter (Ruhr), North Rhine-Westphalia

-

A 1923 50 million mark coin with Vom Stein's likeness from the era of hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic

-

Bust of von Stein in front of the old University of Marburg

See also

In Spanish: Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom Stein para niños

In Spanish: Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom Stein para niños