History of Alexandria, Virginia facts for kids

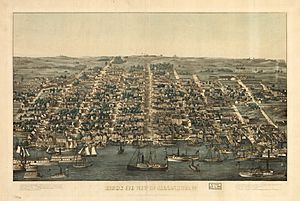

The history of Alexandria, Virginia, began with the first European settlers arriving in 1695. For the next 100 years, Alexandria grew into an important port city. In 1801, a large part of Alexandria became part of the new District of Columbia. During the War of 1812, the city was damaged, like much of the capital. In 1846, Alexandria was returned to Virginia, along with other land west of the Potomac River. When Virginia left the United States in 1861, Union soldiers quickly took over Alexandria. They held it for the rest of the American Civil War. In the late 1900s, Alexandria became a key part of the fast-growing Northern Virginia area.

Contents

Early European Settlement

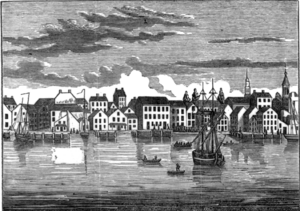

The first European settlement in this area started in 1695. At that time, it was part of the English Colony of Virginia. In 1730, Virginia passed a law about tobacco. This law said that all tobacco grown in the colony had to be taken to special warehouses for inspection before it could be sold. One of these warehouses was planned near the Potomac River, at the mouth of Hunting Creek. However, the land there wasn't good enough. So, the warehouse was built a bit further up the river, where the water was deep near the shore.

In 1745, Virginia lost a long argument with Lord Fairfax. This argument was about the western border of his land, called the Northern Neck Proprietary. After London decided in favor of Lord Fairfax, some wealthy people from Fairfax County formed the Ohio Company of Virginia. They wanted to trade with people living further inland in America. For this, they needed a trading center close to where ships could easily travel on the Potomac River. The tobacco warehouse at Hunting Creek was the best spot for a port that could handle sailing ships.

Around 1746, Captain Philip Alexander II moved to what is now south of Duke Street in Alexandria. His large property was near Hunting Creek, Hooff’s Run, the Potomac River, and roughly where Cameron Street is today. In 1748, people from Fairfax County asked the government to create a town at the Hunting Creek Warehouse. Lawrence Washington (1718-1752), a representative for Fairfax County and a member of the Ohio Company, supported this idea. His younger brother, George Washington, who was a surveyor, even drew a map showing why the warehouse site was good for a town.

Philip Alexander didn't like the idea of a town on his land. He preferred a site further up Hunting Creek. To solve this, the people who wanted the town offered to name it Alexandria, to honor Philip's family. So, Philip and his cousin, Captain John Alexander, gave land to help build the new town. They are known as the founders. On May 2, 1749, the government approved the river location. An auction for town lots was held in July 1749. At first, the town was called "Belhaven" by its founders, possibly after a Scottish patriot. This name was used for a while, but it was never officially approved by the government. The town of Alexandria officially became a city in 1779.

In 1755, General Edward Braddock planned his military trip against Fort Duquesne from Carlyle House in Alexandria. In April 1755, governors from several colonies met in Alexandria. They met to plan how to work together against the French in America.

In March 1785, leaders from Virginia and Maryland met in Alexandria. They talked about trade between their two states. They finished their meeting at Mount Vernon. This meeting, called the Mount Vernon Conference, led to an agreement for free trade and travel on the Potomac River. Maryland then suggested a meeting for all states to discuss trade rules. This led to the Annapolis Convention of 1786, which then led to the creation of the U.S. Constitution at the Federal Convention of 1787.

Part of the District of Columbia

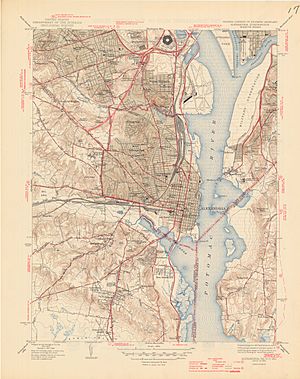

In 1791, George Washington chose Alexandria to be part of the new District of Columbia. A part of Alexandria, known as "Old Town," and all of today's Arlington County were originally part of Virginia. They were given to the U.S. Government to form the District of Columbia. Later, in 1846, this land was given back to Virginia. This happened when the District was made smaller, to only include the land north of the Potomac River. The City of Alexandria was officially re-established in 1852.

In 1814, during the War of 1812, a British fleet attacked Alexandria. The city surrendered without a fight. As part of the surrender, the British took goods from stores and warehouses. They mainly took flour, tobacco, cotton, wine, and sugar.

From 1828 to 1836, Alexandria was home to the Franklin & Armfield Slave Market. This was one of the largest slave trading companies in the country. By the 1830s, they were sending over 1,000 enslaved people each year from Alexandria to markets in Mississippi and Louisiana. Later, this slave pen became a jail when the Union army occupied Alexandria.

Returning to Virginia

Over time, many people in Alexandria wanted to leave the District of Columbia. The city's economy was struggling. It faced competition from the port of Georgetown and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. Also, Alexandria residents had lost their right to vote and have representatives in any level of government.

Alexandria was also a big port and market for the slave trade. There was growing talk about ending slavery in the national capital. If slavery were outlawed, Alexandria's economy would suffer a lot. At the same time, there was a strong movement to end slavery in Virginia. The state's government was divided on the issue. If Alexandria returned to Virginia, it would add more representatives who supported slavery.

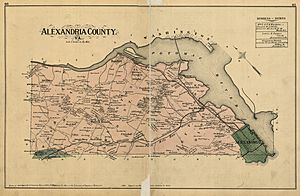

After a vote, the people asked Congress and Virginia to return the area to Virginia. Congress gave the area back to Virginia on July 9, 1846. The City of Alexandria later became separate from Alexandria County in 1870. The rest of Alexandria County changed its name to Arlington County in 1920.

The American Civil War

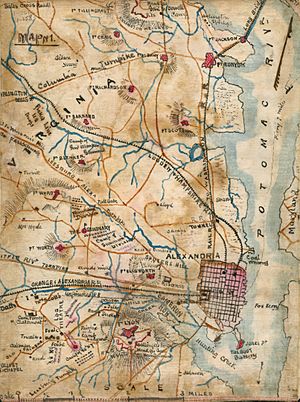

The first deaths for both the North and South in the American Civil War happened in Alexandria. About a month after the Battle of Fort Sumter, Union troops took over Alexandria. They landed at the base of King Street on May 24, 1861. A few blocks away, Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth, a Union commander, went with a small group to take down a large Confederate flag. This flag was flying on the roof of the Marshall House Inn and could be seen from the White House. As Ellsworth came down from the roof, the hotel owner, James W. Jackson, killed him. One of Ellsworth's soldiers immediately shot Jackson.

Colonel Ellsworth was from Illinois and often visited the White House. His death was a great sadness. After he died, he was seen as a hero in the North. This event caused a lot of excitement in the North. Jackson's death caused a similar, but smaller, reaction in the South.

Alexandria remained under military control until the end of the Civil War. One of the forts built by the Union army to defend Washington, D.C. was Fort Ward, located within Alexandria's current borders. From 1863 until the end of the war, Alexandria was the capital of the Restored Government of Virginia. This government was loyal to the Union.

During the Union occupation, there was often tension between the people of Alexandria and the soldiers. The military sometimes insisted that church services include prayers for the President of the United States. Because the Episcopal Church used a prayer book that specifically mentioned government leaders, Episcopal priests faced problems when Union forces occupied their areas.

St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Alexandria was the site of a famous incident. On February 9, 1862, Union troops arrested the interim minister, Rev. Dr. K. J. Stewart, in the church. They had come to cause trouble. During the service, a Union officer ordered Dr. Stewart to say the prayer for the President, which he had skipped. Dr. Stewart ignored him. Then, a captain and six soldiers drew their weapons, went into the church, grabbed the minister while he was kneeling, and forced him out of the church and into the guard-house. Dr. Stewart was soon released but was not allowed to lead services anymore.

The day after the Alexandria Gazette reported this event, its offices were set on fire. St. Paul's Church was then closed for the rest of the war. Its records were also destroyed by fire. During the war, the church was used by the Union army as a hospital for wounded soldiers.

Buildings at Virginia Theological Seminary and Episcopal High School also served as hospitals for Union troops. Bullets and other items from the Civil War have been found in these areas even into the 1900s. Christ Church, because of its connection to George Washington, was not closed. However, army chaplains controlled it for the war's duration.

For African American enslaved people who escaped, the Union occupation of Alexandria created huge opportunities. As Federal troops took over more Southern states, escaped enslaved people came into Union-controlled areas. Alexandria and Washington offered not only more freedom but also jobs. During the war, the Union army turned Alexandria into a major supply center, transport hub, and hospital center.

Because escaped enslaved people were still legally considered property until slavery ended, they were called contrabands. This prevented them from being returned to their enslavers. Contrabands worked for the army as construction workers, nurses, longshoremen, painters, wood cutters, drivers, laundresses, cooks, gravediggers, personal servants, and later as soldiers and sailors. By the fall of 1863, Alexandria's population had grown to 18,000 people. This was an increase of 10,000 people in just 16 months.

After the Fifteenth Amendment was passed, Alexandria County's black population was over 8,700. This was about half of all residents in the County. These newly enfranchised citizens helped elect the first black Alexandrians to the City Council and the Virginia Legislature.

Many of the contrabands who came to Alexandria were very poor, didn't have enough food, and were sick. Once in Alexandria, they lived in barracks and quickly built shantytowns. In these crowded, unsanitary places, smallpox and typhoid outbreaks were common, and many people died. In February 1864, after hundreds of contrabands and freedmen had died, General John P. Slough, the commander of the Alexandria military district, took some undeveloped land. This land was at the corner of South Washington and Church Streets and belonged to someone who supported the Confederacy. It was used as a cemetery specifically for contrabands. Burials started in March of that year.

The cemetery was run under General Slough's command. The Rev. Albert Gladwin, Alexandria’s Superintendent of Contrabands, oversaw it and arranged burials. Each grave had a white wooden marker. In 1868, after the Freedmen's Bureau stopped most of its work, the cemetery was closed. The property was given back to its original owners. Over time, the grave markers rotted, and the land was sold several times. Eventually, it was used for businesses. During its five years of operation, about 1,800 contrabands and freedmen were buried in the cemetery.

In 1987, people remembered the cemetery and the City of Alexandria began working to save it and create a memorial park. In 2008, a design for the memorial was chosen from entries submitted by 20 countries. By late 2008, construction of the memorial was underway. The cemetery, now called Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery, was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in August 2012.

20th Century and Beyond

In 1914, the Agudas Achim Congregation was founded. In 1930, Alexandria took over the Town of Potomac. This town, next to Potomac Yard, had been planned in the late 1800s and officially became a town in 1908.

During Prohibition (when alcohol was illegal), the city's only brewery, Robert Portner Brewing Company, closed. Alexandria did not have a brewery again until the Port City Brewing Company opened in 2011.

In 1969 and 1976, Pope John Paul II visited Alexandria when he was known as Karol Cardinal Wojtyła. A Polish Catholic priest from St. Mary's Catholic Church in Alexandria guided him.

In 1999, the city celebrated its 250th birthday.

In 2014, a law was proposed in the City Council to change a 1963 rule. This old rule required new north-south streets to be named after Confederate military leaders.

Images for kids

-

Child laborers working at a glass factory in Alexandria, 1911. Photo by Lewis Hine.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |