History of Anatolia facts for kids

The history of Anatolia (also known as Asia Minor) covers a very long time! It starts with the first humans and goes all the way to modern Turkey. We can divide it into different periods:

- Prehistory: From the first humans until about 2000 BCE.

- Ancient Anatolia: This includes the Hattian, Hittite, and later periods.

- Classical Anatolia: When the Achaemenid (Persian), Hellenistic (Greek), and Roman empires were in charge.

- Byzantine Anatolia: The time of the Eastern Roman Empire, which later saw the arrival of the Seljuks and Ottomans.

- Ottoman Anatolia: From the 14th to the 20th century.

- Modern Anatolia: Since the country of Turkey was created.

Contents

Prehistory

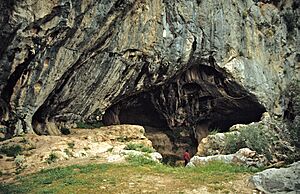

Prehistory covers the time before writing was invented, so we learn about it from archaeology. In 2014, a stone tool found in the Gediz River was proven to be 1.2 million years old! This shows humans were in Anatolia a very long time ago. Footprints from 27,000 years ago have also been found.

Anatolia is a special place because it connects Asia and Europe. Many early civilizations grew here. Some important early settlements include Çatalhöyük, Çayönü, Göbekli Tepe, and Mersin.

Ancient Anatolia

Early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age began in Anatolia around 3000 BCE. This is when people learned to mix copper and tin to make bronze. The region became known as the "Land of Hatti", named after the ancient Hattians. Later, this name was used for the land ruled by the Hittites.

Around 2400 BCE, the Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia became interested in Anatolia. They wanted to trade for materials like copper. However, the Akkadian Empire fell around 2150 BCE.

Middle Bronze Age

After the Akkadians, the Old Assyrian Empire took over the trade routes, especially for silver. They used advanced trading systems, as shown by records found in Kanesh.

The Hittite Old Kingdom started to grow stronger during this time. They conquered the city of Hattusa in the 17th century BCE, which became their capital. The Minoan culture on Crete was also influenced by Anatolia during this period.

Late Bronze Age

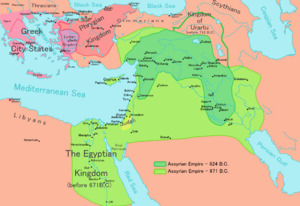

The Hittite Empire was very powerful in the 14th century BCE. It controlled central Anatolia, parts of Syria, and Mesopotamia. They had treaties with other empires to keep peace and manage trade routes.

Around 1180 BCE, the Hittite Empire broke apart. This was partly due to the arrival of mysterious groups called the Sea Peoples. The empire split into smaller "Neo-Hittite" city-states. We know about the Hittites from clay tablets with cuneiform writing found in their old cities.

Iron Age

After the Bronze Age ended, Ionian Greeks settled on the west coast of Anatolia. They built many Greek city-states there. This is where Western philosophy first began!

The Phrygian Kingdom formed after the Hittite Empire fell. They built their capital at Gordium. The Phrygians adopted many Hittite customs.

One famous Phrygian king was King Midas. Legends say he could turn anything he touched into gold. Historically, King Midas lived around 740-696 BCE. He was known to the Assyrians as King Mita. The Assyrians saw him as a strong enemy. However, the Cimmerians invaded Phrygia, leading to King Midas's downfall in 696 BCE.

Maeonia and the Lydian Kingdom

Lydia was an important kingdom in western Anatolia. It was first called Maeonia. The Heraclid dynasty ruled Lydia for a long time, from 1185 to 687 BCE. But Greek cities like Smyrna and Ephesus grew stronger, and the Heraclids became weaker.

The last Heraclid king was murdered by his friend, Gyges, who then became king. Gyges fought against the Greeks and also faced attacks from the Cimmerians. Lydia eventually took over Phrygia.

Under King Croesus, Lydia became very wealthy. He minted the world's first bimetallic coins (gold and silver). Croesus attacked the Persian king Cyrus II, but was defeated in 546 BCE. This led to Lydia becoming part of the Persian Empire.

Classical Anatolia

Achaemenid Empire

After defeating Lydia, the Persian Empire, founded by Cyrus the Great, continued to expand. They used a system of local governors called satraps.

In 502 BCE, a revolt started on Naxos Island. This led to the Ionian Revolt, where Greek cities in Anatolia fought against the Persians. With help from Athens, the revolt spread. The Persians eventually crushed the revolt in 494 BCE. This made the Persian king Darius I very angry at Athens, leading to later wars between Persia and Greece.

The Persians controlled Caria, but their local ruler, Hecatomnus, gained a lot of power for his family. His son, Mausolus, moved the capital to Halicarnassus (modern Bodrum) and built a strong navy. He also started building a huge tomb for himself, which became known as the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. His family ruled Caria for about 20 more years until Alexander the Great arrived.

Hellenistic Anatolia

Alexander the Great

In 336 BCE, Alexander the Great became king of Macedon. He quickly built a large army and navy to fight the Persians. In 334 BCE, he landed in Anatolia and defeated the Persian army at the Battle of the Granicus.

Alexander then freed the western coast of Anatolia, including Lydia and Ionia. Instead of fighting the powerful Persian navy at sea, he decided to capture every city along the Mediterranean coast. This weakened the Persian navy. He then moved inland, through Phrygia, Cappadocia, and Cilicia.

At the Battle of Issus, Alexander's smaller army defeated the Persian king Darius III. Darius fled, leaving his family behind. This victory freed Anatolia from Persian rule forever.

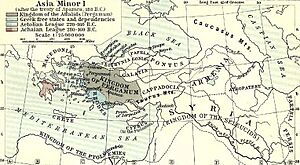

Wars of the Diadochi and division of Alexander's empire

After Alexander died suddenly in 323 BCE, his generals, called the Diadochi, fought over his empire. Eventually, three strong leaders divided the empire after the Battle of Ipsus:

- Ptolemy took southern Anatolia, Egypt, and the Levant, forming the Ptolemaic Empire.

- Lysimachus controlled western Anatolia and Thrace.

- Seleucus claimed the rest of Anatolia, forming the Seleucid Empire.

Only the Kingdom of Pontus in northern Anatolia managed to stay independent.

Seleucid Empire

Seleucus I Nicator built a new capital city called Antioch. He also created a large army and divided his empire into 72 provinces for easier management. After Seleucus died, his empire faced many challenges.

His son, Antiochus I, fought off attacks but couldn't stop the kingdom of Pergamon from becoming independent in 262 BCE. Later, a war with Egypt (the Third Syrian War) led to the Seleucids losing more territory.

Parthia and Pergamon before 200 BCE

In the east, the Parthian Empire broke away from the Seleucids in 245 BCE. This new kingdom grew to control a large area.

The kingdom of Pergamon in western Anatolia also became independent. Under King Attalus I, Pergamon expanded its territory and even defeated the Galatians and a Seleucid army. However, the Seleucids later regained some control.

These events showed that the Seleucid Empire was weakening in Anatolia. The powerful Roman Empire was about to enter the scene.

Roman Anatolia

Roman intervention in Anatolia

Rome became involved in Anatolia after its war with Hannibal. In 215 BCE, Hannibal allied with Philip V of Macedon. Rome sent a small navy to prevent Macedonian expansion in western Anatolia. Attalus I of Pergamon and the city of Rhodes convinced Rome that war with Macedon was necessary. Rome defeated Philip's army in 197 BCE.

Later, the Seleucid king Antiochus III ventured into Greece, which Rome saw as a threat. Rome defeated him in Greece and then again in Anatolia at the Battle of Magnesia in 189 BCE.

Because of the Treaty of Apamea in 188 BCE, Pergamon gained much of the Seleucid land in Anatolia. Rhodes also received territory. However, Rome started to limit Pergamon's power, showing that Rome was now the main power in the region.

The interior of Anatolia had other kingdoms like Pontus and Cappadocia. Pontus had been independent for a long time. Bithynia, another kingdom, always had good relations with Rome.

In 133 BCE, the last king of Pergamon, Attalus III, left his kingdom to Rome. This new territory became the Roman province of Asia. This was a major step in Rome's control of Anatolia.

The Mithridatic Wars

The Mithridatic Wars were a series of conflicts between Rome and Mithridates VI of Pontus. In 90 BCE, while Rome was busy with internal problems, Mithridates invaded Bithynia and the Roman province of Asia. He even encouraged Greeks to kill as many Romans and Italians as possible in an event called the Asiatic Vespers.

The Roman general Cornelius Sulla defeated Mithridates, forcing him to give up most of his lands in the Treaty of Dardanos.

In 74 BCE, Bithynia also became a Roman province. Mithridates attacked again. Rome sent Lucius Licinius Lucullus to fight him, driving Mithridates back into the mountains.

Finally, the great Roman general Pompey took over the war. He pushed Mithridates all the way back to the Bosphorus. Mithridates took his own life in 63 BCE. This allowed Rome to take full control of Pontus and Cilicia. By 25 BCE, the last independent kingdom in Anatolia, Galatia, also became a Roman province. Anatolia was now completely under Roman rule.

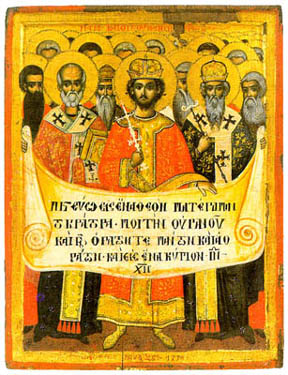

Christianity in Anatolia during Roman times

Jewish communities were present in Anatolia during Roman times. For example, Antiochus III moved 2,000 Jewish families to Lydia and Phrygia around 210 BCE.

Christianity began to grow rapidly in Anatolia in the 1st century CE. The letters of St. Paul in the New Testament show this growth, especially in the province of Asia. He mentioned churches in Colossae and Troas. Later, the Book of Revelation mentions the Seven Churches of Asia: Ephesus, Magnesia, Thyatira, Smyrna, Philadelphia, Pergamon, and Laodicea. By 112 CE, the Roman governor of Bithynia noted that many people were becoming Christians.

Anatolia before the 4th century: Peace and the Goths

From the time of Emperor Augustus until Constantine I, Anatolia enjoyed a long period of peace and growth. Debts were removed, roads were built, and agriculture thrived. This wealth helped the region recover from natural disasters like earthquakes. Many famous scholars came from Anatolia during this time, including the philosopher Dio Chrysostom and the doctor Galen.

However, by the mid-3rd century, a new enemy appeared: the Goths. They invaded Anatolia, first landing in Trebizond in 256 CE. They stole wealth and ships and moved inland. A second invasion brought more destruction to Bithynia, with cities like Nicomedia and Chalcedon being sacked. The Goths even launched a third attack, destroying the Temple of Diana in Ephesus in 263 CE.

Byzantine Anatolia

The Roman Empire became unstable. In 330 CE, Emperor Constantine I made a big decision: he moved the capital from Rome to the old city of Byzantium, renaming it Constantinople. He made the city very strong and supported Christianity. He even helped lead the First Council of Nicaea to settle religious disagreements.

After Constantine's death in 337 CE, his sons fought for control, leading to violence and instability. Eventually, Constantius II became the sole emperor. Later, Julian the Apostate tried to reverse the progress of Christianity, but he died after only a year and a half.

In 379 CE, Emperor Gratian chose the general Theodosius I to rule the eastern empire. Theodosius quickly healed religious divisions, stopping Arianism and pagan practices. By 395 CE, when the Roman Empire officially split into Western and Eastern halves, the Eastern Roman Empire (also called the Byzantine Empire) was very strong.

The Byzantine Empire was the Greek-speaking continuation of the Roman Empire. Its capital was Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). It survived for over a thousand years after the Western Roman Empire fell, until it was conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

Persian intervention

The Sassanid Persians fought many wars against the Byzantines. Their attacks, and a siege of Constantinople in 626 CE, weakened the Byzantines and opened the way for a new threat: the Arabs.

Arab conquests and threats

Arab armies conquered large parts of the Byzantine Empire, significantly reducing its territory.

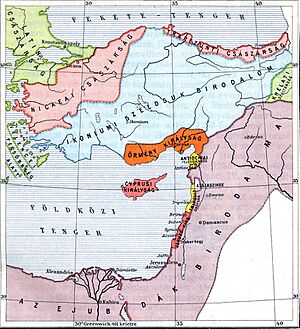

The Seljuks and Anatolian Beyliks

Turkic people began migrating into Anatolia between the 6th and 11th centuries. Many arrived in the 11th century as part of the Seljuk Empire. The Seljuks gradually conquered parts of the Byzantine Empire in Anatolia.

The Seljuks were a branch of the Oghuz Turks. After their victory at the Battle of Manzikert on August 26, 1071, Anatolia became a new homeland for Oğuz Turkic tribes.

The Seljuk victory led to the creation of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum, a separate part of the larger Seljuk Empire. It also led to the formation of many smaller Turkish states called beyliks.

The Crusades and their effects

The four Crusades, which involved the Byzantines, greatly weakened their power and caused disunity that they could never fully recover from.

Mongol invasion and aftermath

On June 26, 1243, the Seljuk armies were defeated by the Mongols at the Battle of Kosedag. The Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm then became a vassal state of the Mongols, losing much of its power. Hulegu Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan, founded the Ilkhanate, which ruled Anatolia through Mongol governors. The last Seljuk sultan died in 1308.

The Mongol invasions caused many Turkomans to move to Western Anatolia. These Turkomans founded several Anatolian beyliks under Mongol rule. The most powerful were the Karamanids and Germiyanids. Along the Aegean coast were the Karasids, Sarukhanids, Aydinids, Menteşe, and Teke. The Jandarids controlled the Black Sea region.

The Beylik of the Ottoman Dynasty was a small, unimportant state in northwest Anatolia at this time. However, over the next 200 years, this small beylik would grow into the mighty Ottoman Empire, expanding across the Balkans and Anatolia.

Breakaway successor states and the fall

The new Turkish states gradually squeezed the Byzantine Empire. It was only a matter of time before Constantinople, the Byzantine capital, was finally captured by the Ottomans in 1453.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Anatolia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Anatolia para niños

- History of Turkey

- History of the Middle East

- Timeline of Middle Eastern history

- Anatolianism

- Anatolian peoples

- Anatolian hypothesis

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |