History of Poland during the Piast dynasty facts for kids

| 960–1385 | |

Banner of the Kingdom of Poland

|

|

| Preceded by | Civitas Schinesghe |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Kingdom of Poland (1385–1569) |

| Monarch |

|

The Piast dynasty ruled Poland from the 10th to the 14th century. This was the first big step in the history of the Polish state. The dynasty began with dukes like Siemowit, Lestek, and Siemomysł. Around 960 AD, Mieszko I, Siemomysł's son, is seen as the true founder of Poland. The Piast family ruled Polish lands until 1370.

In 966, Mieszko I became a Christian in an event called the Baptism of Poland. This was a huge moment for Poland's culture and its place in Europe. Mieszko also united different Lechitic tribes, which was key to forming the new country.

After Poland became a state, its rulers helped people become Christian. In 1025, they created the Kingdom of Poland. Mieszko's son, Bolesław I the Brave, set up a Catholic Church center in Gniezno. He also conquered new lands and was crowned the first King of Poland in 1025.

The first Piast kingdom faced problems after King Mieszko II Lambert died in 1034. But it was brought back by Casimir I in 1042. However, Poland became a duchy (ruled by a duke) again, not a kingdom. Duke Casimir's son, Bolesław II the Bold, was a strong military leader like Bolesław I. But he got into a serious fight with Bishop Stanislaus of Szczepanów and had to leave the country.

Bolesław III, the last duke of this early time, successfully defended Poland and got back lost lands. When he died in 1138, Poland was divided among his sons. This split the country into many smaller parts, which weakened the Piast rule for a long time.

Later, Konrad I of Masovia asked the Teutonic Knights for help against the Baltic Prussian pagans. This led to many centuries of wars between Poland and the Knights. In 1320, the kingdom was reunited under Władysław I the Elbow-high. His son, Casimir III the Great, made it even stronger and bigger.

After the country split, Poland lost its western areas of Silesia and Pomerania. So, Poland started to expand towards the east instead. This period ended with two rulers from the Capetian House of Anjou between 1370 and 1384. The strong kingdom built in the 14th century set the stage for the powerful Polish kingdom that followed.

Contents

- Poland's Early History: 10th-12th Century

- Mieszko I and Poland Becomes Christian (960–992)

- Bolesław I and the Polish Kingdom (992–1025)

- Mieszko II and the Kingdom's Troubles (1025–1039)

- Poland Reunited Under Casimir I (1039–1058)

- Bolesław II and the Conflict with Bishop Stanisław (1058–1079)

- Władysław I Herman's Rule (1079–1102)

- Bolesław III's Rule (1102–1138)

- Poland Splits Apart (1138–1320)

- Culture in Early Medieval Poland

- Poland in the 13th Century

- Poland in the 14th Century

- See also

Poland's Early History: 10th-12th Century

Mieszko I and Poland Becomes Christian (960–992)

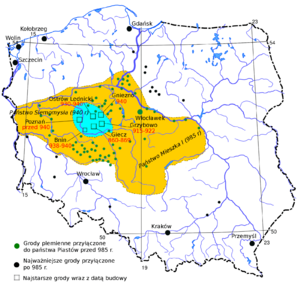

In the early 900s, the Polans tribe in what is now Greater Poland started to form a state. They settled in flat areas around places like Giecz, Poznań, Gniezno, and Ostrów Lednicki. Between 920 and 950, they rebuilt old forts and built new, strong ones. The Polish state grew from these tribal roots in the second half of the 10th century.

A writer from the 12th century, Gallus Anonymus, said the Polans were ruled by the Piast dynasty. The first Piast ruler mentioned in old writings was Mieszko I. A German writer, Widukind, wrote that Mieszko's forces were beaten twice in 963 by tribes working with a Saxon exile. Under Mieszko's rule (around 960 to 992), his tribal state accepted Christianity and became the country of Poland.

Mieszko's new state grew stronger by taking over more land. Starting from a small area around Gniezno, the Piast family expanded throughout the 10th century. They eventually controlled an area similar to modern-day Poland. The Polans tribe conquered and joined with other Slavic tribes. First, they formed a group of tribes, then a single state. Mieszko's state grew to include Lesser Poland and Silesia. These areas were taken from the Czech state. By then, Mieszko's state had its main regions, which were seen as ethnically Polish. The Piast lands covered about 250,000 square kilometers and had less than a million people.

Mieszko I was the first ruler of the Polans known from written records. He was originally a pagan. In 965, Mieszko allied with the Duke of Bohemia and married his Christian daughter, Doubravka. Mieszko became a Christian on April 14, 966. This event, known as the Baptism of Poland, is seen as the start of the Polish state. After Mieszko won a battle in 967, the first missionary bishop, Jordan, was appointed for Poland. This helped stop the German church from expanding too much into Poland.

Mieszko's state had a tricky relationship with the German Holy Roman Empire. Mieszko was a friend and ally of Emperor Otto I. He paid tribute from the western parts of his lands. Mieszko fought wars with other Slavic groups and German leaders. His victories helped him expand his lands in Pomerania to the west. After Otto I died, Mieszko supported a different person for emperor. Around 980, Mieszko married Oda von Haldensleben after Doubravka died. By 990, Mieszko I officially put his country under the Pope's authority. He had made Poland one of the strongest powers in central-eastern Europe.

Bolesław I and the Polish Kingdom (992–1025)

When Mieszko I died in 992, his son Bolesław became ruler, even though his father had other plans. Bolesław had to fight his stepmother, Oda, and her young sons to take the throne. Bolesław was Mieszko's oldest son from his first wife. He managed to remove his stepmother and stepbrothers to become the only ruler of Poland. Bolesław I Chrobry ("the Brave") was a very ambitious and strong leader.

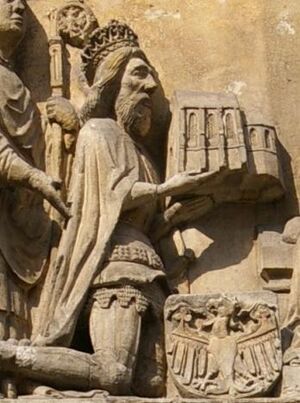

One of Bolesław's main goals was to build up the Polish church. He became friends with Adalbert of Prague, a Czech bishop and missionary. Adalbert was killed in 997 while on a mission in Prussia. Bolesław cleverly used Adalbert's death. Adalbert became a saint for Poland, which led to an independent Polish Catholic Church. In the year 1000, Emperor Otto III visited Adalbert's grave. He supported Bolesław during the Congress of Gniezno. The Gniezno Archdiocese and other church areas were set up then. The Polish church became a vital support for the Piast state in difficult times.

Bolesław first continued his father's friendly policy with the Holy Roman Empire. But when Emperor Otto III died in 1002, Bolesław's relationship with the new emperor, Henry II, became difficult. This led to several wars (1002–1005, 1007–1013, 1015–1018). From 1003 to 1004, Bolesław got involved in Czech family conflicts. After his troops left Bohemia in 1018, Bolesław kept Moravia. In 1013, Bolesław's son Mieszko married Richeza of Lotharingia, the niece of Emperor Otto III. This marriage was important for future Polish rulers. The wars with Germany ended in 1018 with the Peace of Bautzen, which was good for Bolesław. In 1018, Bolesław also took over western Red Ruthenia. In 1025, just before he died, Bolesław I got permission from the Pope to crown himself. He became the first King of Poland.

Bolesław's plans to expand Poland were expensive and not always successful. For example, he lost the important area of Farther Pomerania in 1005. This region had been hard-won by Mieszko.

Mieszko II and the Kingdom's Troubles (1025–1039)

King Mieszko II Lambert (ruled 1025–1034) tried to continue his father's expansion plans. But his actions made Poland's neighbors angry. His two brothers, who had lost their power, used this anger to arrange invasions from Germany and Kievan Rus' in 1031. Mieszko was defeated and had to leave Poland. Mieszko's brother Bezprym was killed in 1032. His other brother, Otto, died in 1033. These events allowed Mieszko to get some of his power back.

However, the first Piast kingdom fell apart when Mieszko died in 1034. Without a strong government, Poland suffered from a rebellion by pagans and common people. In 1039, forces from Bohemia invaded. The country lost land, and the Gniezno church was disrupted.

Poland Reunited Under Casimir I (1039–1058)

Poland recovered under Mieszko's son, Duke Casimir I (ruled 1039–1058). He is known as "the Restorer." After returning from exile in 1039, Casimir rebuilt the Polish monarchy and got back lost lands. In 1047, he took back Masovia from a Polish noble who tried to separate it. In 1054, Silesia was recovered from the Czechs. Casimir got help from Germany and Kievan Rus', who didn't like the chaos in Poland.

Casimir introduced a more developed system of feudalism. He stopped paying for large armies from the duke's own money. Instead, he gave land to his warriors, who then had to serve him. Because much of Greater Poland was destroyed after the Czech invasion, Casimir moved his court to Kraków. Kraków replaced the old Piast capitals of Poznań and Gniezno. Kraków would be the capital for many centuries.

Bolesław II and the Conflict with Bishop Stanisław (1058–1079)

Casimir's son, Bolesław II the Bold (ruled 1058–1079), made Poland's military strong. He led several campaigns between 1058 and 1077. Bolesław supported the Pope in his conflict with the German emperor. With the Pope's blessing, Bolesław crowned himself king in 1076. In 1079, there was a plot against Bolesław involving the Bishop of Kraków. Bolesław had Bishop Stanisław of Szczepanów executed. Because of this, Bolesław was forced to give up his throne by the Catholic Church and powerful nobles. Stanisław later became the second patron saint of Poland.

Władysław I Herman's Rule (1079–1102)

After Bolesław was exiled, his younger brother Władysław I Herman (ruled 1079–1102) ruled Poland. Władysław relied heavily on Count Palatine Sieciech, a powerful noble who controlled much of the government. Władysław's two sons, Zbigniew and Bolesław, forced their father to remove Sieciech. From 1098, Poland was divided among the three of them. After Władysław's death, from 1102 to 1106, it was divided between the two brothers.

Bolesław III's Rule (1102–1138)

After a struggle, Bolesław III Wrymouth (ruled 1102–1138) became the Duke of Poland. He defeated his half-brother Zbigniew in 1106–1107. Zbigniew had to leave Poland but got support from the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, who attacked Poland in 1109. Bolesław defended his country thanks to his military skills, determination, and alliances. Zbigniew later returned and died in mysterious circumstances.

Bolesław's other major success was conquering all of Mieszko I's Pomerania. His father, Władysław I Herman, started this task, and Bolesław finished it around 1123. Szczecin was taken over after a bloody fight. Western Pomerania became Bolesław's fief, ruled by Wartislaw I.

Around this time, efforts to make the region Christian began seriously. This led to the creation of the Pomeranian Wolin Diocese after Bolesław died in 1140.

Poland Splits Apart (1138–1320)

Before he died, Bolesław III Wrymouth divided the country among four of his sons. He made complex plans to prevent fighting between them and keep Poland united. But after Bolesław's death, his plan failed. This started a long period where Poland was split into many parts. For almost two centuries, the Piast rulers fought each other, the church, and the nobles for control.

Bolesław's plan was supposed to be stable because of the "senior duke" system. The senior duke was based in Kraków and ruled a special area that could not be divided. Bolesław divided the country into five main areas: Silesia, Greater Poland, Masovia, Sandomierz, and Kraków. His four sons got the first four areas and became independent rulers. The fifth area, Kraków, was for the oldest prince, who would be the Grand Duke of Poland. This system broke down quickly. Bolesław III's sons, Władysław II the Exile, Bolesław IV the Curly, Mieszko III the Old, and Casimir II the Just, fought for power and control over Kraków.

The borders Bolesław III left were similar to those of Mieszko I. However, this original Polish state did not survive the period of division.

Culture in Early Medieval Poland

After Poland's leaders became Christian in the 10th century, foreign churchmen came to Poland. The culture of early Medieval Poland grew as part of Christian Europe. It took a few generations for many Polish churchmen to appear. After many monasteries were built in the 12th and 13th centuries, more people became Christian.

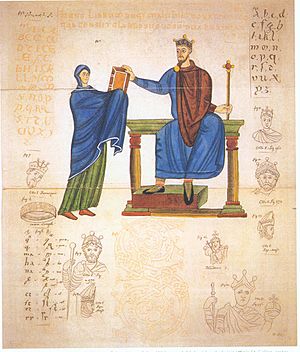

Learning and art were centered around the Church, the courts of kings and dukes, and wealthy families. Written records began in the late 10th century. Rulers like Mieszko II and Casimir the Restorer were educated. An important document from this time is the Dagome iudex. Another key source is the Gesta principum Polonorum, a history written by Gallus Anonymus, a foreign churchman at Bolesław Wrymouth's court.

Bruno of Querfurt was one of the first Western churchmen to spread reading and writing. Some of his important writings were made in monasteries in Poland. Early religious groups included the Benedictines (their abbey in Tyniec was founded in 1044) and the Cistercians. Many stone churches were built starting in the 10th century, often with palaces for rulers. Later, true Romanesque buildings appeared. The first coins were made by Bolesław I around 995. The Gniezno Doors at Gniezno Cathedral, made of bronze in the 1170s, are beautiful examples of Romanesque art in Poland.

Poland in the 13th Century

Society, German Settlers, and Changes

The 13th century brought big changes to Polish society and its government. Because of constant internal fights, the Piast dukes could not keep Poland's borders stable. Western Farther Pomerania broke away from Poland in the late 1100s. From 1231, it became part of Brandenburg. In 1307, Brandenburg took even more land in Pomerania. Pomerelia (Gdańsk Pomerania) became independent from Polish dukes in 1227. In the mid-1200s, Bolesław II the Bald gave Lubusz Land to Brandenburg. This created the Neumark region and caused problems for Poland's western border. In the southeast, Leszek the White could not keep Poland's control over the Halych area of Rus'; this land changed hands many times.

Social status became more based on how much land a person owned. This included land controlled by the Piast princes, wealthy landowners, church groups, and knights. Workers ranged from "free" hired people to serfs tied to the land, and even slaves. The most powerful feudal lords, first the Church and then others, gained special rights. They were largely free from court rules and taxes that dukes used to collect.

Civil wars and foreign invasions, like the Mongol invasions in 1240/1241, 1259/1260, and 1287/1288, weakened and emptied many small Polish areas. Poland became more and more divided. This loss of people and a greater need for workers led to many West European peasants moving to Poland. Most were German settlers. The first groups from Germany and Flanders arrived in the 1220s. These new settlements often had special legal rights, based on German town laws.

German immigrants also helped cities grow and created a class of Polish burghers (city merchants). They brought Western European laws (Magdeburg rights) and customs, which Poles adopted. From that time, Germans became an important minority in Poland. They formed strong communities, especially in the cities of Silesia and western Poland.

In 1228, the Acts of Cienia were passed by Władysław III Laskonogi. The Duke of Poland promised to provide "just and noble law" with the help of bishops and nobles. These legal promises and rights also included lower-level landowners and knights. They were becoming the lower and middle nobility, later known as szlachta. The period of division weakened the rulers. It started a trend where the rights of the nobility grew at the expense of the king.

Relations with the Teutonic Knights

In 1226, Duke Konrad I of Masovia asked the Teutonic Knights for help. He wanted them to fight the pagan Old Prussians, who lived next to his lands. There was a lot of border fighting, and Konrad's area was suffering from Prussian attacks. The Old Prussians were also being forced to become Christian, but it wasn't working well.

The Teutonic Order soon went beyond the land Konrad gave them. In the next decades, they conquered large areas along the Baltic Sea coast. They set up their own monastic state. Almost all Western Baltic pagans were converted or killed. The Knights then faced Poland and Lithuania, which was the last pagan state in Europe. Wars between the Teutonic Knights and Poland and Lithuania continued for most of the 14th and 15th centuries. The Teutonic state in Prussia was increasingly settled by Germans. It was claimed as a fief and protected by popes and Holy Roman Emperors.

Attempts to Reunite Poland (1232–1305)

As the problems of political division became clear, some Piast dukes tried to reunite Poland. Important early attempts were made by the Silesian dukes Henry I the Bearded, his son Henry II the Pious (killed in 1241 fighting Mongols at the Battle of Legnica), and Henry IV Probus. In 1295, Przemysł II of Greater Poland became the first Piast duke crowned King of Poland since Bolesław II. But he only ruled part of Poland and was killed soon after.

A more complete uniting of Polish lands was done by a foreign ruler, Václav II of Bohemia. He married Przemysł's daughter and became King of Poland in 1300. Václav's harsh rule made him lose support. He died in 1305.

The Polish Church was important in reuniting the country. It stayed as one church area throughout the time of division. Archbishop Jakub Świnka of Gniezno strongly supported reuniting Poland. He crowned both Przemysł II and Václav II. Świnka also supported Władysław I Łokietek at different times.

Culture in the 13th Century

Culturally, the Church had a much wider impact in the 13th century. Many parishes were set up, and cathedral schools became more common. The Dominicans and the Franciscans were the main religious groups. They worked closely with the general population. Many written records and laws appeared during this time. More churchmen were Polish, and others were expected to know the Polish language. Wincenty Kadłubek, who wrote an important history, was a leading thinker. Perspectiva, a book about optics by Witelo, a Silesian monk, was a great achievement in medieval science. Building churches and castles in the Gothic architecture style was common in the 13th century. Polish elements in art became more important. There were also big improvements in farming, manufacturing, and crafts.

Poland in the 14th Century

The Reunited Kingdom and Jewish Settlement

Władysław I the Elbow-high and his son Casimir III, "the Great" were the last two Piast rulers. They ruled a reunited Kingdom of Poland in the 14th century. Their rule was not exactly like Poland before it split. The country had lost some unity and land. Regional Piast princes remained strong, and some leaned towards Poland's neighbors for economic and cultural reasons.

Poland lost Pomerania and Silesia, which were its most developed and important regions. This meant half of the Polish people lived outside the kingdom's borders. The western losses happened because efforts to unite Poland by the Silesian Piast dukes failed. Also, German expansion and settlement led to some Polish ruling families becoming more German. The lower Vistula River was controlled by the Teutonic Order. Masovia was not fully part of Poland yet.

Casimir made the western and northern borders stable. He tried to get back some lost lands. He also expanded Poland to the east, bringing in areas that were East Slavic and not ethnically Polish.

Even with less land, 14th-century Poland grew economically and became more prosperous. Farming settlements expanded and became more modern. Towns grew, and trade, mining, and metalwork increased. Casimir III also made big changes to the money system.

Jewish people had been settling in Poland for a long time. In 1264, Duke Bolesław the Pious of Greater Poland gave them the Statute of Kalisz. This law gave Jews many freedoms for their religion, travel, and trade. It also protected Jews from local harassment. The law said Jews could not be enslaved. This was the start of Jewish prosperity in Poland. Many other similar laws followed. After Jews were expelled from Western Europe, Jewish communities grew in Kraków, Kalisz, and other parts of western and southern Poland in the 13th century. More communities were set up in Lviv, Brest-Litovsk, and Grodno further east in the 14th century. King Casimir welcomed Jewish refugees from Germany in 1349. This helped Jewish communities in Poland grow until World War II. German town and country settlements were another lasting ethnic feature.

Władysław I the Elbow-high's Rule (1305–1333)

Władysław I the Elbow-high (ruled 1305–1333) started as a less known Piast duke. He fought a long and hard battle against powerful enemies. When he died as king of a partly reunited Poland, the kingdom was still in a difficult situation. Even though Władysław controlled a limited area, he might have saved Poland's existence as a state.

With help from his ally Charles I of Hungary, Władysław returned from exile. He challenged Václav II and his successor Václav III between 1304 and 1306. Václav III's murder in 1306 ended the Bohemian family's involvement in Poland. After this, Władysław took over Lesser Poland, entering Kraków. He also took lands north of there, through Kuyavia to Gdańsk Pomerania. In 1308, Brandenburg conquered Pomerania. To get it back, Władysław asked the Teutonic Knights for help. The Knights brutally took over Gdańsk Pomerania and kept it for themselves.

In 1311–1312, a rebellion in Kraków was started by the city's wealthy leaders. They wanted to be ruled by the House of Luxembourg. This rebellion was put down. This event may have limited the growing political power of towns.

In 1313–1314, Władysław conquered Greater Poland. In 1320, he became the first Polish king crowned in Kraków's Wawel Cathedral instead of Gniezno. The Pope agreed to the crowning, despite opposition from King John of Bohemia, who also claimed the Polish crown. John tried to attack Kraków in 1327 but had to stop. In 1328, he went on a crusade against Lithuania and made an alliance with the Teutonic Order. The Order was at war with Poland from 1327 to 1332. As a result, the Knights captured Dobrzyń Land and Kujawy.

Władysław was helped by his alliances with Hungary (his daughter Elizabeth married King Charles I in 1320) and Lithuania (a pact in 1325 against the Teutonic State and his son Casimir marrying Aldona, daughter of the Lithuanian ruler Gediminas). After 1329, a peace deal with Brandenburg also helped him. A lasting achievement of King John of Bohemia (and a big loss for Poland) was his success in forcing most of the Piast Silesian areas to become loyal to him between 1327 and 1329.

Casimir III the Great's Rule (1333–1370)

After Władysław I died, his 23-year-old son became King Casimir III. He was later known as Casimir the Great (ruled 1333–1370). Unlike his father, the new king did not like military life. People at the time didn't think Casimir had much chance of solving the country's growing problems. But from the start, Casimir acted wisely. In 1335, he bought King John of Bohemia's claims to the Polish throne. In 1343, Casimir settled several disputes with the Teutonic Order. This led to the Treaty of Kalisz in 1343, where Dobrzyń Land and Kuyavia were returned to Poland.

At that time, Poland began to expand to the east. Through several military campaigns between 1340 and 1366, Casimir added the Halych–Volodymyr area of Rus'. The town of Lviv there attracted people of many nationalities. It was given city rights in 1356. Lviv became the main Polish center among a Rus' Orthodox population. With support from Hungary, the Polish king promised the Hungarian ruling family the Polish throne if he died without sons.

Casimir officially gave up his rights to several Silesian areas in 1339. He tried to get the region back by fighting the House of Luxembourg (the rulers of Bohemia) between 1343 and 1348. But then he stopped the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV from trying to separate Silesia from the Gniezno Archdiocese. Later, until his death, he tried to claim Silesia legally by asking the Pope. His successors did not continue his efforts.

Allied with Denmark and Western Pomerania, Casimir was able to make some changes to the western border. In 1365, Drezdenko and Santok became Poland's fiefs. The Wałcz district was taken completely in 1368. This action cut off the land connection between Brandenburg and the Teutonic state. It also connected Poland with Farther Pomerania.

Casimir the Great made Poland much stronger both at home and abroad. Inside the country, he united and centralized the Polish state. He helped develop what was called the "Crown of the Polish Kingdom"—the state within its actual and potential borders. Casimir created or strengthened national institutions, like the powerful state treasury. These institutions were independent of regional or royal court interests. Internationally, the Polish king was very active in diplomacy. He had close ties with other European rulers and strongly defended Poland's interests. In 1364, he hosted the Congress of Kraków. Many monarchs attended this meeting, which aimed to promote peace and political balance in Central Europe.

Louis I and Jadwiga's Rule (1370–1399)

Right after Casimir died in 1370, his nephew Louis of Hungary became the Polish king. Casimir had no sons. Casimir's promise for Louis to take the throne seemed uncertain. So, Louis started talking with Polish knights and nobles in 1351. They supported him, but in return, they demanded more guarantees and rights for themselves. This was formally agreed to in Buda in 1355. After his crowning, Louis went back to Hungary. He left his mother, Elizabeth (Casimir III's sister), as regent in Poland.

With Casimir the Great's death, the time of hereditary (Piast) kings in Poland ended. Landowners and nobles did not want a strong king. A constitutional monarchy was set up between 1370 and 1493. This included the start of the general sejm, which would become the main parliament.

During Louis I's rule, Poland and Hungary were united. In a pact from 1374 (the Privilege of Koszyce), the Polish nobility gained many rights. They agreed that Louis's daughters could inherit the throne, as Louis had no sons. Louis neglected Polish affairs, which led to the loss of lands Casimir had gained. This included Halych Rus', which Queen Jadwiga got back in 1387. In 1396, Jadwiga and her husband Jagiełło forcefully took over central Polish lands. These lands separated Lesser Poland from Greater Poland. King Louis had previously given them to his Silesian Piast ally, Duke Władysław of Opole.

The union between Hungary and Poland lasted for twelve years and ended in war. After Louis died in 1382, there was a power struggle and a civil war in Greater Poland. The Polish nobility decided that Jadwiga, Louis's youngest daughter, should become the next "King of Poland." Jadwiga arrived in 1384 and was crowned at age eleven. The failure of the union with Hungary opened the way for the union of Lithuania and Poland.

Culture in the 14th Century

In the 14th century, many large brick buildings were constructed during Casimir's rule. These included Gothic churches, castles, city walls, and homes for wealthy city residents. The most famous examples of medieval architecture in Poland are the many churches in the Polish Gothic style. Medieval sculptures, paintings, and metalwork are best seen in church furnishings and religious items.

Polish law was first written down in the Statutes of Casimir the Great (the Piotrków–Wiślica Statutes) from 1346 to 1362. This meant that conflicts were solved through legal processes within the country. Also, talks and treaties between countries became more important in international relations. By this time, there were many cathedral and parish schools. In 1364, Casimir the Great founded the University of Kraków. It was the second oldest university in Central Europe. While many still traveled to Southern and Western Europe for university studies, the Polish language, along with Latin, became more common in written documents. The Holy Cross Sermons (around early 14th century) are possibly the oldest Polish prose manuscript still existing.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Polonia durante la dinastía Piasta para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Polonia durante la dinastía Piasta para niños

- Poland in the Early Middle Ages

- History of Poland during the Jagiellonian dynasty

- Slavery in Poland