History of Poland during the Jagiellonian dynasty facts for kids

| 1385–1572 | |

Banner of Poland-Lithuania

|

|

| Preceded by | Piast dynasty |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Early elective monarchy |

| Monarch |

|

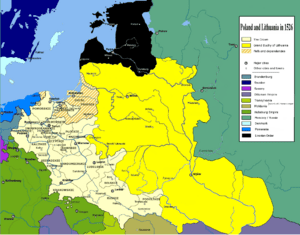

The Jagiellonian dynasty ruled Poland from 1386 to 1572. This time period covers the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the Modern Era in Europe. The dynasty began when Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, married Queen Jadwiga of Poland in 1386. He then became King Władysław II Jagiełło of Poland.

This marriage created a strong partnership between Poland and Lithuania. It brought a huge amount of land from Lithuania under Poland's influence. Both the Polish and Lithuanian people benefited from this union. They worked together in one of Europe's largest political groups for about 400 years.

During this time, Poland often fought the Teutonic Knights in the Baltic Sea area. A major battle was the Battle of Grunwald in 1410. Later, the Peace of Thorn in 1466 helped shape the future of Prussia. In the south, Poland faced the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Tatars. In the east, Poland helped Lithuania against the growing power of Moscow. Poland and Lithuania also expanded their lands to include Livonia in the far north.

Under the Jagiellonians, Poland became a feudal state. This meant that land was owned by nobles, and most people worked on farms. The landed nobility (rich landowners) became very powerful. In 1505, a law called Nihil novi gave most of the law-making power to the Sejm (parliament), not the king. This started the "Golden Liberty" system. Here, the "free and equal" Polish nobility ruled the country and chose their king.

The 1500s also saw the Protestant Reformation spread in Poland. This led to a unique policy of religious tolerance, which was rare in Europe back then. The Renaissance also brought a huge cultural flowering to Poland. This was especially true under the last Jagiellonian kings, Sigismund I the Old (1506–1548) and Sigismund II Augustus (1548–1572).

Contents

- Poland in the Middle Ages (14th–15th Century)

- Early Modern Era (16th Century)

- Farming and Trade Growth

- Townspeople and Nobles

- The Reformation in Poland

- Polish Renaissance Culture

- The Republic of Nobles

- Military and Foreign Policy

- Prussia and the Baltic Sea

- Wars with Moscow

- Jagiellons, Habsburgs, and Ottomans

- Livonia and Baltic Control

- Poland and Lithuania: A Real Union

- The Commonwealth: Diverse and Noble-Ruled

- Jewish Settlement

- See also

Poland in the Middle Ages (14th–15th Century)

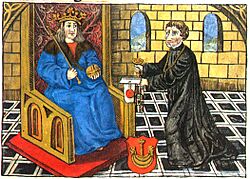

The Jagiellonian Kings

In 1385, the Union of Krewo was signed. It was an agreement between Queen Jadwiga of Poland and Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania. Lithuania was the last pagan state in Europe at that time. The agreement led to Jogaila's baptism and his marriage to Jadwiga. This started the Polish–Lithuanian union. After his baptism, Jogaila was known as Władysław II Jagiełło in Poland.

This union made both nations stronger. They could better stand against the Teutonic Knights and the rising power of Moscow. Lithuania controlled vast lands in the east, including areas near the Black Sea. These lands had many Eastern Orthodox people. The union connected two different parts of Europe: the Western Christian world and the Eastern Christian world.

At first, the goal was to create one common state under King Władysław Jagiełło. But Polish leaders soon realized that fully joining Lithuania into Poland was not possible. Sometimes, Poland and Lithuania even fought each other. The Jagiellonian kings then focused Poland's attention more on the eastern lands.

From 1386 to 1572, the Polish–Lithuanian union was ruled by Jagiellonian kings. The kings' power slowly decreased over time. The rich landowners (nobility) gained more and more power in the government. However, the Jagiellonian family brought stability to Poland. This era is often seen as a time of great power, wealth, and a "Golden Age" for Polish culture.

Society and Economy

In the 1400s, the system where peasants paid rent for land changed. Nobles started to control farming, trade, and other businesses more tightly. They created large farms called folwarks. On these farms, peasants were forced to work for free instead of paying rent. This made many peasants into serfs, meaning they were tied to the land. Laws were passed to support this. For example, a 1496 law stopped townspeople from buying rural land and made it hard for peasants to leave their villages.

Polish towns kept some self-government, like city councils. But they had little power in the national government. The nobility also stopped doing their main duty: fighting in wars when needed. In 1505, the Nihil novi law made it so the king had to ask the Senate and the Sejm (parliament) before making new laws. This meant the king's power was limited.

Poland and Lithuania United

The first king of the Jagiellonian dynasty was Władysław II Jagiełło. He became King of Poland in 1386 after marrying Jadwiga of Poland. He also converted to Catholicism, and Lithuania became Christian. King Jagiełło had a rivalry with his cousin Vytautas the Great in Lithuania. They settled this in 1392 and 1401, with Vytautas becoming Grand Duke of Lithuania under Jagiełło. This agreement helped Poland and Lithuania work together against the Teutonic Order. The Union of Horodło in 1413 gave special rights to Catholic nobles in Lithuania.

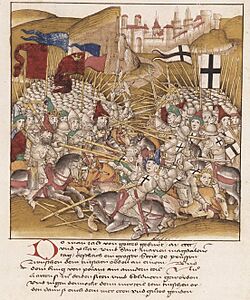

Fighting the Teutonic Knights

A big war with the Teutonic Knights happened from 1409 to 1411. It ended with the huge Battle of Grunwald (also called Tannenberg). Here, the combined armies of Poland and Lithuania-Rus' completely defeated the Teutonic Knights. However, they failed to capture the Knights' main fortress, Malbork. This failure had long-term consequences for Poland.

The Peace of Thorn in 1411 gave Poland and Lithuania only small land gains. Later, in 1415, a scholar from Kraków Academy, Paulus Vladimiri, argued that pagans had a right to live peacefully and be independent. This was a very modern idea for the time. More fighting and peace deals followed, ending with the Treaty of Melno in 1422.

The Hussite Movement and Hungary

During the Hussite Wars (1420–1434), Poland was involved in politics concerning the Czech crown. Bishop Zbigniew Oleśnicki was a strong opponent of joining with the Hussite Czech state.

Jagiellonian kings were not automatically chosen by birth. Each new king had to be approved by the nobles. King Władysław Jagiełło had two sons late in life. In 1430, the nobles agreed that his son Władysław III would be the next king, but only after Jagiełło made some promises. When Jagiełło died in 1434, his young son Władysław became king, with Bishop Oleśnicki leading the government.

In 1438, the Czechs offered their crown to Jagiełło's younger son, Casimir. This led to two failed Polish military trips to Bohemia. After Vytautas died in 1430, Lithuania had its own internal wars. Casimir was sent to Lithuania in 1440 and was surprisingly made Grand Duke there.

Oleśnicki then focused on uniting Poland with Hungary. Hungary was threatened by the Ottoman Empire. In 1440, Władysław III became King of Hungary. He led the Hungarian army against the Ottomans in 1443 and 1444. Sadly, Władysław III was killed in the Battle of Varna.

Casimir IV Becomes King

In 1445, Casimir, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, was asked to become King of Poland after his brother Władysław died. Casimir was a tough negotiator. He only accepted the Polish throne in 1447 on his own terms. As king, Casimir gained more power from Cardinal Oleśnicki and his group. He also settled a dispute with the Pope over who could choose bishops.

War with the Teutonic Order Ends

In 1454, cities and nobles in Prussia, who were against the Teutonic Knights, asked King Casimir to take over Prussia. This led to the Thirteen Years' War (1454–66). The Polish army was weak at first because the nobles wouldn't help without promises from Casimir. These promises were written in the Statutes of Nieszawa in 1454.

The war ended with the Second Peace of Thorn in 1466. The Teutonic Knights had to give the western half of their land to Poland. This area became known as Royal Prussia. The remaining part became Ducal Prussia, which was under Polish rule. Poland also got back Pomerelia, which gave it access to the Baltic Sea. The city of Gdańsk (Danzig) also helped by fighting naval battles.

Wars with Turks and Tatars

The Jagiellonian family's influence grew in Central Europe during the 1400s. In 1471, Casimir's son Władysław became King of Bohemia, and in 1490, King of Hungary. However, the southern and eastern parts of Poland and Lithuania were threatened by Turkish invasions.

In 1485, King Casimir led an army into Moldavia after the Ottoman Turks took its seaports. The Crimean Tatars, supported by the Turks, raided eastern lands in 1482 and 1487. King John Albert, Casimir's son, fought them. More Tatar raids happened in 1498, 1499, and 1500. Peace efforts started by John Albert ended in 1503, leading to an unstable truce.

Tatar invasions continued in 1502 and 1506 during King Alexander's rule. In 1506, the Tatars were defeated at the Battle of Kletsk.

Moscow's Threat and Sigismund I

The Grand Duchy of Moscow became a growing threat to Lithuania in the 1400s and 1500s. Moscow took many of Lithuania's eastern lands in wars in 1471, 1492, and 1500. Lithuania needed Poland's help to balance power in the east.

After King John Albert died, Grand Duke Alexander of Lithuania was elected King of Poland in 1501. In 1506, Sigismund I the Old became ruler of both Poland and Lithuania. This brought the two states even closer. Sigismund had been a Duke in Silesia, but he did not try to claim Silesia for Poland.

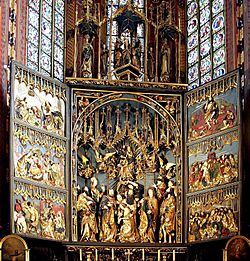

Culture in the Late Middle Ages

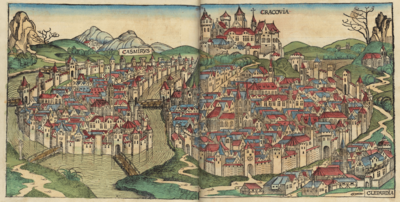

Polish culture in the 1400s was still very medieval. However, crafts and industries grew, and their products spread widely. Paper making began, and printing developed in the late 1400s. The first Latin print in Poland was in Kraków in 1473. The famous Altar of Veit Stoss in St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków is a beautiful example of Gothic art from this time.

The University of Kraków was revived around 1400. Queen Jadwiga and the Jagiellonian kings supported it. It even got a theology department. Europe's oldest math and astronomy department was founded there in 1405. Famous scholars like Copernicus' teacher, Albert of Brudzewo, studied there.

Early Polish humanists like John of Ludzisko and Archbishop Gregory of Sanok were professors at the university. Jan Długosz, a historian, wrote a huge history of medieval Poland. Foreign humanists also came to Poland. Filippo Buonaccorsi from Italy, known as Kallimach, tutored Casimir IV's sons.

Early Modern Era (16th Century)

Farming and Trade Growth

The folwark system, large farms worked by serfs, became very important in Poland from the late 1400s. This was different from Western Europe, where capitalism and industry were growing. The farming boom in the 1500s, with cheap peasant labor, made folwark farms very profitable.

Mining and metalworking also grew in the 1500s. Poland exported many farm and forest products, mostly by river to ports. This gave Poland a positive trade balance. Most grain left Poland through Gdańsk (Danzig). Gdańsk became the richest and most independent Polish city because of its location on the Vistula River and access to the Baltic Sea. It was also a major manufacturing center. Other towns like Kraków, Poznań, and Warsaw also benefited from trade.

Townspeople and Nobles

In the 1500s, rich merchant and banking families, many of German origin, did big business in Europe. Some areas of Poland were very urbanized. For example, in Greater and Lesser Poland, 30% of people lived in cities by the late 1500s. Many sons of townspeople studied at the Kraków Academy and foreign universities. They contributed greatly to Polish Renaissance culture.

The nobility (or szlachta) made up a larger part of the population in Poland than in other countries, up to 10%. All nobles were supposed to be equal, but some had no land and couldn't hold office. Others, called magnates, owned huge estates with many towns and villages.

The 1500s in Poland were officially a "republic of nobles." The "middle class" of nobles became very important. However, magnate families still held the highest government and church jobs. The szlachta in Poland and Lithuania came from many different ethnic and religious backgrounds. During this time of tolerance, this didn't usually affect their wealth or careers. The Renaissance szlachta were proud of their "freedoms." They valued education, followed current events, and traveled widely. Foreigners often noted the grand homes and lavish spending of wealthy Polish nobles.

The Reformation in Poland

The Polish Church had problems, which made it easier for Reformation ideas to spread. Many nobles were jealous of the Church's wealth and power.

The ideas of Martin Luther were popular in German-speaking areas like Silesia and Prussia. In Gdańsk in 1525, a Lutheran uprising happened but was put down by King Sigismund I the Old. Königsberg and the Duchy of Prussia became centers for spreading Protestant ideas. King Sigismund I tried to stop the spread of Lutheranism with laws, but they were not very effective.

King Sigismund II Augustus, Sigismund I's son, was much more tolerant. By 1559, he allowed Lutherans to practice their religion freely in Royal Prussia. Besides Lutheranism, other groups like Anabaptists and Unitarians also gained followers among the nobility.

Calvinism became popular in the mid-1500s among nobles and magnates, especially in Lesser Poland and Lithuania. Calvinists, led by Jan Łaski, wanted to unite all Protestant churches into a Polish national church. King Sigismund II supported this idea, but the Pope refused. In 1563, Łaski and others published the Brest Bible, a Polish translation of the Bible. After 1563–1565, full religious tolerance became common. The Catholic Church was weakened but not destroyed, which helped the later Counter-Reformation.

Among Calvinists, disagreements led to a split in 1562. Two churches were formed: mainstream Calvinist and the smaller, more radical Polish Brethren (or Arians). Some Arians were pacifists and believed in sharing property. A major Polish Brethren center was in Raków until 1638. The Sandomierz Agreement of 1570 was a compromise among Polish Protestant groups, but it excluded the Arians.

The Warsaw Confederation in 1573 guaranteed religious freedom and peace for the nobility. This made Poland a "safe haven for heretics" in 16th-century Europe.

Polish Renaissance Culture

Golden Age of Polish Culture

The Polish "Golden Age" is usually the 1500s, during the reigns of Sigismund I and Sigismund II. This period saw the rise of Polish Renaissance culture. It was supported by the wealth of nobles and rich townspeople in cities like Kraków and Gdańsk. The Renaissance ideas came mostly from Italy. This was helped by Sigismund I's marriage to Bona Sforza. Many Poles traveled to Italy to study, and Italian artists came to Poland.

Early Polish humanists were influenced by Erasmus of Rotterdam. Later, Polish culture developed its own unique elements.

Learning and Books

Printing grew in Kraków from 1473. By the early 1600s, there were about 20 printing houses in Poland. The Kraków Academy and King Sigismund II had large libraries. Smaller book collections became common in noble homes and schools. More people learned to read. By the late 1500s, almost every church parish had a school.

The Lubrański Academy was founded in Poznań in 1519. The Reformation led to many new high schools (gymnasiums), some famous internationally. The Catholic Church responded by creating Jesuit colleges. The Kraków University also offered humanist programs.

The university was very important in the late 1400s and early 1500s. Its math, astronomy, and geography departments attracted many foreign students. But by the mid-1500s, the university faced problems. Many students then chose to study abroad.

Sigismund I the Old built the current Wawel Renaissance castle. He and his son Sigismund II Augustus supported artists and thinkers. Nobles and rich townspeople followed their example.

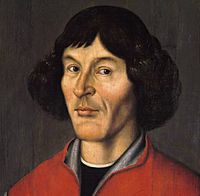

Science

Polish science reached its peak in the early 1500s. People started to question old ideas and seek more logical explanations. Nicolaus Copernicus published his book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium in 1543. This book changed how people understood the universe. It showed that the Earth orbits the Sun, not the other way around. This sparked a huge wave of scientific discovery. Copernicus was from Toruń. He was a poet, an economist, a church administrator, and a political activist.

Josephus Struthius was a famous doctor and medical researcher. Bernard Wapowski was a pioneer in Polish map-making. Maciej Miechowita, a leader at the Kraków Academy, wrote a book in 1517 about the geography of Eastern Europe.

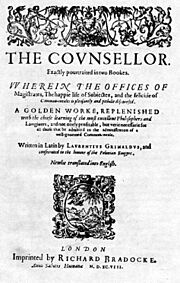

Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski was a major political thinker. His famous work, On the Improvement of the Commonwealth, was published in 1551. He criticized the feudal system and suggested reforms. He believed all social classes should follow the same laws. He also promoted peaceful ways to solve international problems. Bishop Wawrzyniec Goślicki wrote De optimo senatore (The Counsellor) in 1568, which was also popular in the West.

Historian Marcin Kromer wrote important books about Polish history and geography. Marcin Bielski wrote a universal history around 1550.

Literature

Modern Polish literature began in the 1500s. The Polish language became widely used in all parts of public life, including law and the Church. Klemens Janicki, a Latin poet, was from a peasant family. Biernat of Lublin, another commoner, wrote his own version of Aesop's fables in Polish, with social messages.

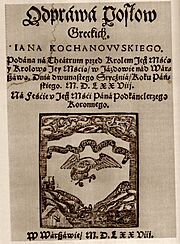

The Reformation helped Polish literature grow. Mikołaj Rej was a key figure. In his 1543 satire, Brief Discourse, he defended a serf. Later, he wrote about the joys of a country gentleman's life. Rej promoted the Polish language in his many works. Łukasz Górnicki improved Polish prose. His friend Jan Kochanowski became one of Poland's greatest poets.

Kochanowski was born in 1530 to a wealthy noble family. He studied at universities in Kraków and Italy. He worked as a royal secretary before settling in his family village. Kochanowski's writing is known for its deep thoughts and beautiful form. His famous works include Frascas (short poems), religious poems, the play The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys, and his highly regarded Threnodies (laments) written after his young daughter died.

Music

Renaissance music grew in Poland, especially at the royal court. King Sigismund I had a choir at Wawel Castle from 1543. The Reformation led to more Polish language church singing. Jan of Lublin wrote music for the organ and other instruments. Polish composers like Wacław of Szamotuły, Mikołaj Gomółka (who set Kochanowski's psalms to music), and Mikołaj Zieleński added Polish and folk elements to their music.

Art and Buildings

Architecture, sculpture, and painting also developed under Italian influence from the early 1500s. Many Italian artists came to Kraków. Francesco Fiorentino worked on the tomb of John Albert. He, along with Bartolommeo Berrecci and Benedykt from Sandomierz, rebuilt the royal castle between 1507 and 1536. Berrecci also built Sigismund's Chapel at Wawel Cathedral. Polish nobles and rich merchants built or rebuilt their homes to look like Wawel Castle. The Sukiennice in Kraków and Poznań City Hall were also rebuilt in the Renaissance style.

Between 1580 and 1600, Jan Zamoyski hired Italian architect Bernardo Morando to build the city of Zamość. The city and its defenses were designed in the Renaissance style.

Many churches have beautiful tombstone sculptures of important people. Jan Maria Padovano and Jan Michałowicz of Urzędów were famous sculptors.

Stanisław Samostrzelnik, a monk, painted miniatures and frescoes.

The Republic of Nobles

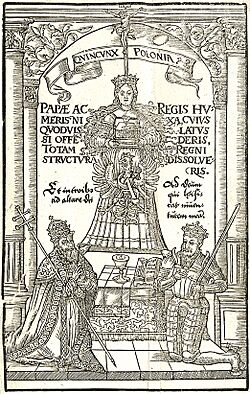

In the 1500s, the middle nobility (szlachta) fought for more power in Poland's government. Kings Sigismund I the Old and Sigismund II Augustus tried to control them. They used their power to appoint officials and influence elections to the Sejm. They also used propaganda and money to support nobles who agreed with them. The kings rarely used force. Eventually, compromises were made. In the second half of the 1500s, Poland had a "democracy of the gentry."

The Sejm, which had two chambers, became the main power in the state. The reform-minded szlachta wanted to limit the power and wealth of the magnates and the church. King Sigismund Augustus supported them in 1562. Over the next decade, the szlachta passed many reforms. These reforms made Poland financially stronger, better governed, and more unified. Some changes were small, and some were never fully put into practice. But the middle szlachta movement was successful for a time.

Mikołaj Sienicki, a Protestant, was a leader of this reform movement. He also helped organize the Warsaw Confederation.

Military and Foreign Policy

Even with economic growth, Poland's military in the 1500s was not very strong compared to threats from the Ottoman Empire, the Teutonic state, the Habsburgs, and Muscovy. The old noble army (pospolite ruszenie) was less useful. Most soldiers were professionals or mercenaries. Their numbers depended on funding approved by the szlachta, which was often not enough. However, the Polish forces and their commanders were good, winning battles against bigger enemies. Poland also had skilled diplomats. Because of limited resources, Poland focused on strengthening its position along the Baltic coast.

Prussia and the Baltic Sea

The Peace of Thorn in 1466 weakened the Teutonic Knights, but didn't solve the problem they posed. Relations worsened after Albrecht became Grand Master in 1511. Poland fought a war in 1519, which ended in a truce in 1521. As a compromise, Albrecht, influenced by Martin Luther, turned the Teutonic Order's state into a secular (non-religious) duchy of Prussia. This duchy became a dependency of Poland, ruled by Albrecht and his family. This agreement, signed in Kraków in 1525, improved Poland's position in the Baltic region. Albrecht paid homage to the King of Poland.

However, Albrecht's family, the House of Hohenzollern, was expanding its power. In 1563, King Sigismund Augustus allowed the Brandenburg branch of the Hohenzollerns to inherit the Prussian duchy. This decision, confirmed in 1569, made it possible for Prussia to unite with Brandenburg later. Sigismund II was careful to show his power over them. But after 1572, Poland was ruled by elected kings, making it harder to stop the Hohenzollerns' growing influence.

In 1568, Sigismund Augustus started to build up a war fleet. He also created the Maritime Commission. This led to conflict with Gdańsk, which felt its trade monopoly was threatened. In 1569, Royal Prussia lost much of its self-rule. In 1570, Poland's control over Gdańsk and Baltic shipping was officially recognized.

Wars with Moscow

In the 1500s, the Grand Duchy of Moscow continued trying to take back old Rus' lands from Lithuania. Lithuania didn't have enough resources to fight Moscow. Polish help became very important to keep the balance of power in the east.

Moscow fought a war with Lithuania and Poland from 1512 to 1522. In 1514, the Russians took Smolensk. That same year, the Polish-Lithuanian army won the Battle of Orsha and stopped Moscow's advance. A truce in 1522 left Smolensk in Russian hands. Another war happened from 1534 to 1537. Polish aid helped take Gomel and defeat Starodub. This led to a new truce and over two decades of peace.

Jagiellons, Habsburgs, and Ottomans

In 1515, a meeting in Vienna arranged a family succession deal between Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor and the Jagiellon brothers, Vladislas II of Bohemia and Hungary and Sigismund I. This was supposed to stop the Emperor from supporting Poland's enemies. But after Charles V became Emperor in 1519, relations with Sigismund worsened.

The Jagiellons' rivalry with the House of Habsburg in Central Europe ended with the Habsburgs gaining power. The Ottoman Empire's expansion greatly weakened the last Jagiellonian monarchies. Hungary became very vulnerable after Suleiman the Magnificent took Belgrade in 1521. To stop Poland from helping Hungary, Suleiman sent a Tatar-Turkish force to raid southeastern Poland–Lithuania in 1524. The Hungarian army was defeated in 1526 at the Battle of Mohács, where young King Louis II Jagiellon was killed. Hungary was then divided between the Habsburgs and the Ottomans.

In 1526, Janusz III of Masovia, the last duke of Masovia, died. This allowed Sigismund I to fully add Masovia to the Polish Crown in 1529.

Poland also had conflicts with Moldavia over the Pokuttya region. A peace treaty in 1538 kept Pokuttya Polish. An "eternal peace" with the Ottoman Empire was made in 1533 to protect border areas.

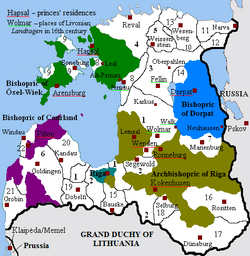

Livonia and Baltic Control

In the 1500s, Lithuania wanted to expand into Livonia to control Baltic seaports like Riga. Livonia was mostly Lutheran and ruled by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. This put Poland and Lithuania against Moscow and other powers.

After the 1525 Treaty of Kraków, Albrecht of Hohenzollern wanted to create a Polish–Lithuanian fief in Livonia. Instead, a pro-Polish–Lithuanian group formed in Livonia. In 1557, the Treaty of Pozvol created a military alliance. Livonia agreed to support Lithuania against Moscow.

Other powers then divided the Livonian state, starting the long Livonian War (1558–1583). Ivan IV of Russia took Dorpat and Narva in 1558. The Danes and Swedes also took parts of Livonia. To protect their country, the Livonians sought a union with Poland–Lithuania. In 1561, Gotthard Kettler, the new Grand Master, declared Livonia a vassal state under the Polish king. The Union of Vilnius created the Duchy of Livonia as an autonomous part of Poland. The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was also created. Sigismund II promised to get back the lands lost to Moscow and other powers. This led to tough wars over control of the Baltic trade. These wars ended during the reign of King Stephen Báthory.

Poland and Lithuania: A Real Union

King Sigismund II had no children. This made it urgent to turn the personal union between Poland and Lithuania into a stronger, more permanent one. This was also a goal of the reform movement. Lithuania's laws were updated from 1529 to 1588, making its system more like Poland's. Fighting wars with Moscow also pushed Poland and Lithuania closer.

Negotiating the union was hard, lasting from 1563 to 1569. Lithuanian magnates worried about losing power. Sigismund II declared that large border regions, including most of Lithuanian Ukraine, would become part of the Polish Crown. This made the Lithuanian magnates rejoin the talks. On July 1, 1569, the Union of Lublin was signed. Lithuania became more secure on its eastern border. Its nobility became more Polonized and contributed greatly to the new Commonwealth's culture.

The Lithuanian language survived as a language for peasants and in religious texts. The Ruthenian language was used officially in Lithuania even after the Union, until Polish took over.

The Commonwealth: Diverse and Noble-Ruled

The Union of Lublin created the unified Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita). It stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Carpathian mountains, and into modern-day Belarus and Ukraine. Poland and Lithuania kept some separate offices, armies, and courts. But they had one monarch, one parliament, one money system, and one foreign policy. Only the nobility had full citizenship rights. The richest nobles (magnates) began to control the rest of the szlachta. This trend became clear after the death of Sigismund Augustus in 1572, the last Jagiellonian king.

The new Commonwealth was very multiethnic and had many different religions. People included Poles (less than 50% of the population), Lithuanians, Latvians, Rus' people (ancestors of today's Belarusians and Ukrainians), Germans, Estonians, Jews, Armenians, Tatars, and Czechs. In the early 1600s, nearly 70% of the population were peasants, over 20% lived in towns, and less than 10% were nobles and clergy. The total population was about 8–10 million and grew quickly. The Slavic people in the eastern lands were mostly Eastern Orthodox, which caused problems later for the Commonwealth.

Jewish Settlement

Poland became home to Europe's largest Jewish population. Royal laws in the 1200s guaranteed Jewish safety and religious freedom. This was different from Western Europe, where Jews faced persecution, especially after the Black Death in 1348–1349. Many Jews fled from German cities to Poland. Poland was mostly spared from the Black Death.

The number of Jews in Poland grew throughout the Middle Ages. By the late 1400s, there were about 30,000. By the 1500s, it reached 150,000 as more refugees arrived. A royal privilege in 1532 allowed Jews to trade anywhere in the kingdom. By the mid-1500s, 80% of the world's Jews lived in Poland and Lithuania. Most of Western and Central Europe was closed to Jews. In Poland–Lithuania, Jews often worked as managers and middlemen, helping to run large noble estates, especially in the eastern borderlands. They became an important part of trade and administration.

See also