History of Lithuania facts for kids

The history of Lithuania begins with people settling there around 10,000 years ago. But the name "Lithuania" was first written down in the year 1009 AD.

Lithuanians are one of the Baltic peoples. They later took over nearby lands. In the 13th century, they created the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. For a short time, they even had a Kingdom of Lithuania. The Grand Duchy was a strong and lasting warrior state. It stayed very independent. It was also one of the last places in Europe to become Christian. This started in the 14th century.

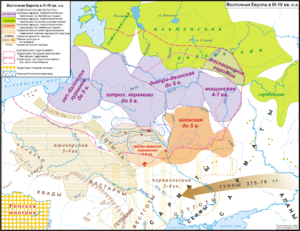

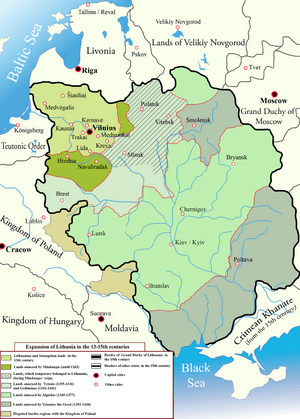

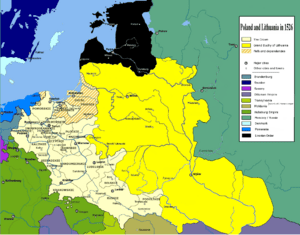

By the 15th century, Lithuania became the largest state in Europe. It stretched from the Baltic Sea all the way to the Black Sea. This happened by taking over lands where many East Slavs lived in a region called Ruthenia.

In 1385, the Grand Duchy joined with Poland through the Union of Krewo. This was a special family agreement. Later, the Union of Lublin in 1569 created the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. This big state lasted until 1795. Then, the Partitions of Poland divided up both independent Lithuania and Poland. After this, Lithuanians lived under the rule of the Russian Empire. This lasted until the 20th century. There were several big rebellions, especially in 1830–1831 and 1863.

On February 16, 1918, Lithuania became a democratic state again. It stayed independent until World War II. Then, the Soviet Union took it over. This was part of a secret deal called the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. After a short time under Nazi Germany, Lithuania was again taken into the Soviet Union. This lasted for almost 50 years. In 1990–1991, Lithuania got its independence back with the Act of the Re-Establishment of the State of Lithuania. Lithuania joined the NATO alliance in 2004. It also joined the European Union in 2004.

Contents

- Early History of Lithuania

- Grand Duchy of Lithuania (13th Century–1569)

- Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795)

- Under Russian Rule and World War I (1795–1918)

- Lithuanian Independence (1918–1940)

- World War II (1939–1945)

- Soviet Period (1944–1990)

- Independence Restored (1990–Present)

- Images for kids

- See also

Early History of Lithuania

First People and Ancient Cultures

The first humans came to what is now Lithuania a very long time ago. This was in the second half of the 10th millennium BC. They arrived after the huge glaciers melted away. These early people were hunters who traveled a lot. They did not build permanent homes.

Around 8,000 BC, the weather became much warmer. Forests grew, and people started to travel less. They hunted, gathered food, and fished in rivers. By 6,000–5,000 BC, people began to tame animals. Their homes also became better for larger families. Farming started much later, around 3,000 BC. This was because of the cold weather and tough land.

Ancient Baltic Tribes

The first Lithuanian people were part of an old group called the Balts. The main Baltic tribes were the West Balts (like the Old Prussians) and the East Balts (like the Lithuanians and Latvians). They spoke different forms of Indo-European languages. Today, only Lithuanians and Latvians remain. Other Baltic groups joined them or were taken over by the State of the Teutonic Order.

The Baltic tribes did not have close ties with the Roman Empire. But they did trade, especially along the Amber Road. The Roman writer Tacitus wrote about the Aesti people around 97 AD. They lived near the Baltic Sea and were likely Balts.

Lithuania was located near the Neman River. It had two main cultural areas: Samogitia in the west and Aukštaitija in the east. This area was far away from others. This helped Lithuanians keep their own language, culture, and religion for a long time.

The Lithuanian language is very old. It is believed to have separated from the Latvian language around the 7th century. Old Lithuanian pagan customs and beliefs were kept for a long time. Rulers were burned after they died until Lithuania became Christian.

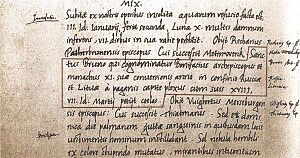

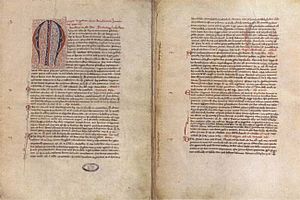

The Lithuanian tribe became more clear around the end of the first thousand years. The first time Lithuania was mentioned as a nation was on March 9, 1009. This was in the writings of a monastery called Quedlinburg. In 1009, a missionary named Bruno of Querfurt came to Lithuania. He baptized the Lithuanian ruler, "King Nethimer."

How the Lithuanian State Began

From the 9th to the 11th centuries, Vikings raided the coastal Balts. Sometimes, the kings of Denmark collected taxes from them. In the 10th and 11th centuries, Lithuanian lands paid tribute to Kievan Rus'. From the mid-12th century, Lithuanians started raiding Ruthenian lands. By the late 12th century, the Lithuanians even threatened the powerful Novgorod Republic.

In the late 12th century, German settlers moved east. This led to fights with Lithuanians. But for a while, the Lithuanians were stronger.

By the late 12th century, Lithuania had an organized army. This army was used for raids, taking goods, and capturing slaves. These activities led to social differences and power struggles. This is how the early Lithuanian state began to form. From this, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania grew.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania (13th Century–1569)

Early Lithuanian State (13th–14th Century)

Mindaugas and His Kingdom

In the early 13th century, Baltic tribes started working together more. This allowed them to launch many military trips. Between 1201 and 1236, they went on 40 trips against Ruthenia, Poland, Latvia, and Estonia. In 1219, 21 Lithuanian chiefs signed a peace treaty with a state called Galicia–Volhynia. This shows that the Baltic tribes were uniting.

Two German crusading groups, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the Teutonic Knights, settled nearby. They claimed to be converting people to Christianity. But they also conquered much of Latvia, Estonia, and parts of Lithuania. In response, many small Baltic tribes united under Mindaugas. Mindaugas was a powerful chief. By 1236, he was seen as the ruler of all Lithuania.

In 1236, the Pope called for a crusade against the Lithuanians. The Samogitians, led by Mindaugas' rival Vykintas, defeated the Livonian Brothers. This happened at the Battle of Saule in 1236. This defeat forced the Brothers to join the Teutonic Knights in 1237. Lithuania was now caught between two parts of this powerful Order.

Around 1240, Mindaugas ruled over Aukštaitija. He then conquered the Black Ruthenia region. Mindaugas tried to expand his control further. He killed rivals or sent family members to conquer and settle in Ruthenia. But these relatives sometimes rebelled.

In 1250, Mindaugas made a deal with the Teutonic Order. He agreed to be baptized in 1251. He also gave up some lands in western Lithuania. In return, he would receive a royal crown. Mindaugas then won against his enemies in 1251. He became the confirmed ruler of Lithuania.

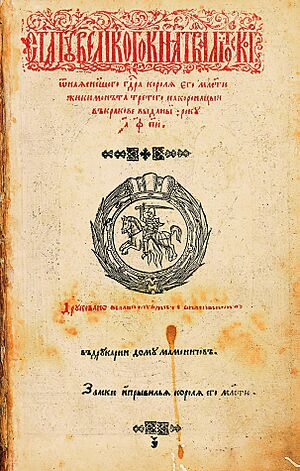

On July 17, 1251, Pope Innocent IV signed orders for Mindaugas to be crowned King of Lithuania. In 1253, Mindaugas was crowned. This created the Kingdom of Lithuania, which was the first and only time in Lithuanian history. Mindaugas gave parts of Yotvingia and Samogitia to the Knights. In 1260, the Samogitians defeated the Teutonic Knights. They agreed to follow Mindaugas if he stopped being Christian. Mindaugas agreed. He started fighting the Teutonic Knights again and expanded his lands in Ruthenia.

Mindaugas was the main founder of the Lithuanian state. He created a Christian kingdom under the Pope. This was at a time when other pagan peoples in Europe were being conquered, not peacefully converted.

Traidenis and Teutonic Conquests

Mindaugas was killed in 1263 by Daumantas of Pskov and Treniota. This led to much trouble and civil war. Mindaugas' son Vaišvilkas ruled next. He was the first Lithuanian duke to become an Orthodox Christian. He settled in Ruthenia, which many others would do later. Vaišvilkas was killed in 1267.

A power struggle followed between Shvarn and Traidenis. Traidenis won. His rule (1269–1282) was the longest and most stable during this time. Traidenis united all Lithuanian lands. He successfully raided Ruthenia and Poland many times. He defeated the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Aizkraukle in 1279. He also became ruler of Yotvingia, Semigalia, and eastern Prussia.

Pagan Lithuania was a target for Christian crusades. In 1241, 1259, and 1275, Lithuania was also attacked by the Golden Horde. After Traidenis died, the German Knights finished conquering the Western Baltic tribes. They then focused on Lithuania, especially Samogitia. This was to connect their two branches of the Order.

Vytenis and Gediminas' Expansion

The family of Gediminas took over the Grand Duchy in 1285. Vytenis (ruled 1295–1315) and Gediminas (ruled 1315–1341) had to deal with constant raids from the Teutonic Orders. These attacks were expensive to fight off. Vytenis fought them well around 1298. He also made an alliance with the German people of Riga.

Gediminas expanded Lithuania's international connections. He wrote letters to Pope John XXII and other European rulers. He invited German settlers to Lithuania. The Pope forced the Knights to have peace with Lithuania from 1324–1327. Gediminas tried to become Christian in 1323–1324. But the Samogitians and his Orthodox courtiers stopped him. In 1325, the son of the Polish king married Gediminas' daughter Aldona. She became queen of Poland. This showed how important the Lithuanian state was under Gediminas.

Under Grand Duke Gediminas, Lithuania became a great power. This was mainly because it expanded a lot into Ruthenia. Lithuania was unique in Europe. It was a pagan-ruled "kingdom" that grew quickly. To pay for its defense against the Teutonic Knights, it had to expand east. Gediminas did this by challenging the Mongols. The fall of Kievan Rus' created a power gap. Lithuania used this to its advantage. Through alliances and conquests, Lithuania gained control of large parts of the former Kievan Rus'.

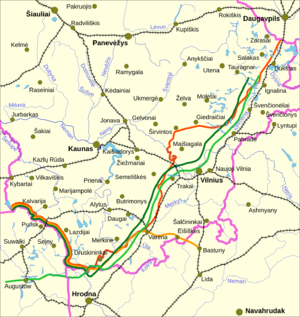

Gediminas' conquests included western Smolensk, southern Polesia, and (for a time) Kyiv. The Lithuanian-controlled area of Ruthenia grew to include most of modern Belarus and Ukraine. This massive state stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea in the 14th and 15th centuries.

In the 14th century, many Lithuanian princes who ruled Ruthenian lands became Orthodox Christian. They adopted Ruthenian customs and names. This helped them connect with their subjects. The Ruthenian lands were much larger and had more people. They also had more developed churches and writing than core Lithuania. The Lithuanian state worked well because of the help from Ruthenian culture.

Algirdas and Kęstutis

Around 1318, Gediminas' older son Algirdas married Maria of Vitebsk. He settled in Vitebsk to rule that area. Of Gediminas' seven sons, four stayed pagan and three became Orthodox Christian. When Gediminas died, he divided his lands among his sons. But Lithuania's military situation, especially against the Teutonic Knights, forced the brothers to keep the country united.

From 1345, Algirdas became the Grand Duke of Lithuania. He ruled over Lithuanian Ruthenia. His equally skilled brother Kęstutis ruled Lithuania proper. Algirdas fought the Golden Horde Tatars and the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Kęstutis took on the tough fight against the Teutonic Order.

The war with the Teutonic Order continued from 1345. In 1348, the Knights defeated the Lithuanians at the Battle of Strėva. Lithuania's situation improved from 1350. Algirdas made an alliance with the Principality of Tver. This brought peace with Poland in 1352.

Bryansk was taken in 1359. In 1362, Algirdas captured Kyiv after defeating the Mongols. Volhynia, Podolia, and left-bank Ukraine were also added to Lithuania. Kęstutis bravely fought to protect ethnic Lithuanians. He tried to push back about 30 attacks by the Teutonic Knights. Kęstutis also attacked the Knights' lands in Prussia many times.

In 1368, 1370, and 1372, Algirdas invaded the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Each time, he reached Moscow itself. An "eternal" peace was made after the last attempt. This was much needed by Lithuania because of heavy fighting with the Knights again.

The two brothers left many ambitious sons. Their rivalry made the country weaker. This was a problem because of the growing power of the Teutonic Knights and the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Moscow was becoming stronger after its victory over the Golden Horde in 1380. It wanted to unite all Rus' lands.

Jogaila, Kęstutis, and Vytautas

Algirdas died in 1377. His son Jogaila became grand duke while Kęstutis was still alive. The Teutonic Knights were very strong. Jogaila wanted to stop defending Samogitia. He wanted to focus on keeping Lithuania's Ruthenian empire. The Knights used the differences between Jogaila and Kęstutis. They made a separate peace with Kęstutis in 1379. Jogaila then made a secret deal with the Teutonic Order in 1380. This was against Kęstutis' wishes.

Kęstutis felt he could no longer support his nephew. In 1381, he entered Vilnius to remove Jogaila from the throne. A civil war began. Kęstutis was captured and died while held by Jogaila. Kęstutis' son Vytautas escaped.

Jogaila made a treaty with the Order in 1382. This showed his weakness. The treaty said Jogaila would become Catholic. It also said he would give half of Samogitia to the Teutonic Knights. Vytautas went to Prussia to get the Knights' help. He wanted to get back his inherited lands. Jogaila refused Vytautas' demands. So, Jogaila and the Knights invaded Lithuania together in 1383. However, Vytautas failed to get all the land he wanted. He then contacted Jogaila. Vytautas switched sides in 1384. He destroyed the border forts the Order had given him. In 1384, the two Lithuanian dukes worked together. They launched a successful trip against the Order's lands.

By this time, Lithuania needed to become Christian. This was for its long-term survival. The Teutonic Knights wanted to connect their Prussian and Livonian lands. They planned to do this by conquering Samogitia and all of Lithuania. The Knights used German and other volunteer fighters. They launched 96 attacks on Lithuania between 1345 and 1382. Lithuanians could only respond with 42 attacks. Lithuania's Ruthenian empire in the east was also in danger. Moscow wanted to unite all Rus' lands. Also, some distant provinces wanted to be independent.

Lithuanian Society in the 13th–14th Century

The Lithuanian state in the late 14th century was mainly two-sided: Lithuanian and Ruthenian. Ruthenian lands are now modern Belarus and Ukraine. Of its huge area, only 10% was ethnic Lithuania. This part probably had no more than 300,000 people. Lithuania needed the people and resources from the Ruthenian lands to survive.

Lithuanian society was becoming more complex. It was led by princes from the Gediminid and Rurik families. Below them were the regular Lithuanian nobility (or boyars). In Lithuania, these nobles were under the princes. They usually lived on small family farms. These farms were worked by a few feudal subjects or slaves. For their military and administrative work, Lithuanian nobles did not have to pay public taxes. They also received Ruthenian land. Most ordinary farm workers were free. But they had to provide crafts and services. If they didn't pay debts, they could be forced into slavery.

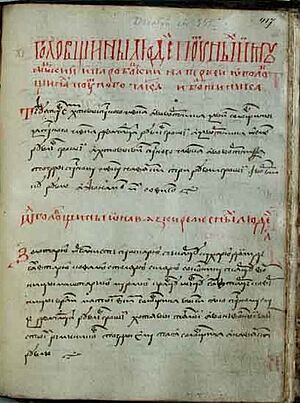

The Ruthenian princes were Orthodox Christian. Many Lithuanian princes also became Orthodox, even some in Lithuania itself. Their wives often converted too. The Ruthenian churches and monasteries had educated monks. They wrote books and collected religious art. Vilnius had a Ruthenian area with their church from the 14th century. The grand dukes' office in Vilnius had Orthodox churchmen. They used a Ruthenian written language for official records. Important documents like the Lithuanian Metrica and Statutes of Lithuania were written in this language.

German, Jewish, and Armenian settlers were invited to live in Lithuania. These groups had their own communities under the dukes. Tatars and Crimean Karaites served as soldiers for the dukes' personal guard.

Towns were not as developed as in nearby Prussia or Livonia. Outside of Ruthenia, the only cities were Vilnius (Gediminas' capital from 1323), the old capital of Trakai, and Kaunas. Vilnius was a major center for trade and culture in the 14th century. It connected central and eastern Europe with the Baltic area. Vilnius merchants had special rights to trade across most of Lithuania. Many foreign merchants settled in Vilnius. The city was ruled by a governor chosen by the grand duke. It had three castles for defense. Both foreign and Lithuanian money was used.

The Lithuanian state had a system where the ruler passed power down in their family. The ruler would choose the son he thought was best to take over. Councils existed, but they could only advise the duke. The large state was divided into smaller areas. These were managed by officials who also handled legal and military matters.

Lithuanians spoke different dialects. But tribal differences were disappearing. The growing use of the name Lietuva showed a developing Lithuanian identity. The new feudal system kept many old ways. These included family clans, free farmers, and some slavery. Land now belonged to the ruler and nobles. The state's organization was based on ideas from Ruthenia.

After Western Christianity was established in the late 14th century, pagan cremation ceremonies became much less common.

Union with Poland and Christianization

Jogaila Becomes Catholic and Rules

As Lithuanian dukes expanded south and east, the East Slavic Ruthenians influenced the Lithuanian ruling class. They brought their Church Slavonic liturgy and the Orthodox Christian religion. They also brought a written language (Chancery Slavonic). This language was used by the Lithuanian court for centuries. It helped make Vilnius a major center of Kievan Rus' culture. By the time Jogaila accepted Catholicism in 1385, many parts of his realm and family had already become Orthodox.

Catholic influence had been growing in northwest Lithuania. This came from German settlers, traders, and missionaries. Franciscan and Dominican friars were in Vilnius since Gediminas' time. Kęstutis in 1349 and Algirdas in 1358 talked about Christianization with the Pope and Polish king. So, the Christianization of Lithuania involved both Catholic and Orthodox ideas. The forced conversions by the Teutonic Knights actually slowed down the spread of Western Christianity.

Jogaila, who became grand duke in 1377, was still pagan. In 1386, Polish nobles offered him the Polish crown. They wanted him to become Catholic and marry the 13-year-old Queen Jadwiga. This deal gave Poland a valuable ally against the Teutonic Knights and Moscow. Lithuania, where Ruthenians greatly outnumbered Lithuanians, could ally with either Moscow or Poland. A deal with Russia was also discussed in 1383–1384. But Moscow was too far to help with the Teutonic Orders. It was also a rival for the loyalty of Orthodox Ruthenians in Lithuania.

Jogaila was baptized, given the name Władysław, married Queen Jadwiga, and was crowned King of Poland in February 1386.

Jogaila's baptism and crowning led to the official Christianization of Lithuania. In 1386, the king returned to Lithuania. The next spring and summer, he took part in mass baptisms for the people. In 1387, a bishopric was set up in Vilnius. Jogaila gave a lot of land and peasants to the Church. This made the Lithuanian Church very powerful. Lithuanian nobles who were baptized also got better legal rights. Vilnius citizens gained self-government. The Church started promoting reading and education. Different social groups began to form.

Jogaila wanted his court and followers to become Catholic. This was to remove the Teutonic Knights' reason for attacking Lithuania. In 1403, the Pope stopped the Order from fighting Lithuania. This ended the two-century threat to Lithuania's existence. Jogaila also needed Polish help in his fight with his cousin Vytautas.

Lithuania's Golden Age Under Vytautas

The Lithuanian Civil War of 1389–1392 involved the Teutonic Knights, Poles, and groups loyal to Jogaila and Vytautas. The grand duchy was badly damaged. Jogaila decided to make peace with Vytautas. Vytautas wanted to get back his inherited lands. He gained much more than that. From 1392, he became the real ruler of Lithuania. This was part of a deal with Jogaila called the Ostrów Agreement. Vytautas was technically Jogaila's regent with more power. Jogaila realized it was better to work with his skilled cousin than to rule Lithuania directly from Kraków.

Vytautas was unhappy with Jogaila's Polish arrangements. He did not want Lithuania to be under Poland. Under Vytautas, the state became more centralized. The Catholic Lithuanian nobles became more important in politics. Vytautas started centralizing power in 1393–1395. He took provinces from several powerful dukes in Ruthenia. The Teutonic Knights invaded Lithuania several times between 1392 and 1394. But Polish forces helped push them back. After this, the Knights stopped trying to conquer Lithuania. They focused on taking and keeping Samogitia.

In 1395, Vytautas conquered Smolensk. In 1397, he won a battle against a part of the Golden Horde. He felt he could now be independent from Poland. In 1398, he refused to pay tribute to Queen Jadwiga. To be free to pursue his goals, Vytautas gave a large part of Samogitia to the Teutonic Order in the Treaty of Salynas of 1398. This greatly improved the Order's military position. Vytautas soon tried to get the territory back. For this, he needed the Polish king's help.

During Vytautas' rule, Lithuania reached its largest size. But his plans to take over all of Ruthenia failed. He suffered a terrible defeat in 1399 at the Battle of the Vorskla River against the Golden Horde. Vytautas realized he needed a lasting alliance with Poland.

The original Union of Krewo was renewed several times. But it was always unclear because of Polish and Lithuanian interests. New agreements were made in the unions of Vilnius (1401), Horodło (1413), and others. In the Union of Vilnius, Jogaila gave Vytautas lifelong rule over the grand duchy. Jogaila kept his formal power. Vytautas promised to be loyal to Poland and the King.

War with the Order started again. In 1403, Pope Boniface IX banned the Knights from attacking Lithuania. But Lithuania still had to agree to the Peace of Raciąż. This treaty had the same terms as the Treaty of Salynas.

Vytautas then focused on the east again. Campaigns between 1401 and 1408 involved Smolensk, Pskov, Moscow, and Veliky Novgorod. Smolensk was kept. Pskov and Veliky Novgorod became dependent on Lithuania. A lasting border between Lithuania and Moscow was agreed in 1408.

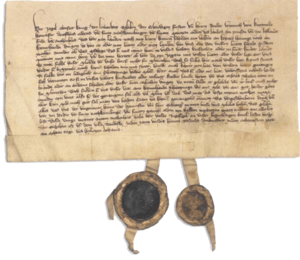

The big war with the Teutonic Knights (the Great War) started in 1409. It began with a Samogitian uprising supported by Vytautas. The Lithuanian–Polish alliance defeated the Knights at the Battle of Grunwald on July 15, 1410. This victory permanently removed the threat the Knights had posed to Lithuania for centuries. The Peace of Thorn (1411) allowed Lithuania to get Samogitia back. But this was only until Jogaila and Vytautas died. The Knights also had to pay a large amount of money.

The Union of Horodło (1413) formally joined Lithuania with Poland again. But in reality, Lithuania became an equal partner. Each country had to agree on the other's future ruler. Catholic Lithuanian nobles got the same rights as Polish nobles. Two administrative areas were set up in Lithuania, like in Poland.

Vytautas allowed different religions. He also tried to influence the Eastern Orthodox Church. He wanted to use it to control Moscow. In 1416, he made Gregory Tsamblak his chosen Orthodox leader for all of Ruthenia. These efforts also aimed to unite the Eastern and Western churches.

The Gollub War with the Teutonic Knights followed. In 1422, the Treaty of Melno gave Samogitia back to Lithuania permanently. This ended Lithuania's wars with the Order. Vytautas' changing policies allowed German East Prussia to survive for centuries. Samogitia was the last region in Europe to become Christian (from 1413).

Vytautas' greatest successes came at the end of his life. The Crimean Khanate and the Volga Tatars came under his influence. In 1426–1428, Vytautas traveled through the eastern parts of his empire. He collected huge tributes from local princes. Pskov and Veliky Novgorod joined the grand duchy in 1426 and 1428. At the Congress of Lutsk in 1429, Vytautas discussed becoming King of Lithuania. This ambition was almost achieved. But it was stopped by last-minute plots and Vytautas' death. Vytautas became a legendary hero.

Changes in Lithuania (Early 15th Century)

The link to Poland brought religious, political, and cultural ties. It also increased Western influence among Lithuanian nobles. This was less true for Ruthenian nobles. Catholics were given special treatment and access to jobs. This was because of Vytautas' policies from 1413. His successors also pushed for Catholic Lithuanian rule over Ruthenian lands. These policies pressured nobles to become Catholic. Ethnic Lithuania was 10% of the area and 20% of the population of the Grand Duchy.

During this time, a group of rich landowners grew. They were also important for the military. A class of feudal serfs (farmers tied to the land) also emerged. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania largely remained a separate state. But Poland tried to bring the Polish and Lithuanian elites closer. Vilnius and other cities got German laws (Magdeburg rights). Crafts and trade grew quickly. Under Vytautas, a network of offices worked. The first schools were set up, and historical records were written. Vytautas opened Lithuania to European culture. He integrated his country with European Western Christianity.

Under Jagiellonian Rulers

The Jagiellonian family, started by Jogaila, ruled Poland and Lithuania from 1386 to 1572.

After Vytautas died in 1430, another civil war happened. Lithuania was ruled by different leaders. Later, Lithuanian nobles twice chose grand dukes on their own. This technically broke the union with Poland. In 1440, they chose Casimir, Jogaila's second son. This was solved when Casimir was also chosen as king by the Poles in 1446. In 1492, Jogaila's grandson John Albert became king of Poland. His other grandson Alexander became grand duke of Lithuania. In 1501, Alexander became king of Poland, solving the issue again. This lasting connection helped Poles, Lithuanians, Ruthenians, and the Jagiellonian rulers.

On the Teutonic front, Poland continued fighting. In 1466, the Peace of Thorn returned many lost lands to Poland. A secular Duchy of Prussia was created in 1525. This would greatly affect Lithuania and Poland's future.

The Tatar Crimean Khanate came under the Ottoman Empire in 1475. The Tatars raided Lithuania for slaves and goods. They burned Kyiv in 1482 and came near Vilnius in 1505. Lithuania lost its lands on the Black Sea shores in the 1480s and 1490s. The last two Jagiellon kings were Sigismund I and Sigismund II Augustus. During their rule, Tatar raids decreased. This was because of the rise of Cossacks and the growing power of the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

Lithuania needed a close alliance with Poland. This was because Moscow threatened some of Lithuania's Rus' lands. Moscow wanted to "recover" lands that were once Orthodox. In 1492, Ivan III of Russia started a series of wars. These were the Muscovite–Lithuanian Wars and Livonian Wars.

In 1492, Lithuania's eastern border was less than 100 miles from Moscow. But because of the wars, Lithuania lost a third of its land to Russia by 1503. The loss of Smolensk in 1514 was especially bad. Even though the Battle of Orsha was won, Poland had to get involved in Lithuania's defense. The peace of 1537 left Gomel as Lithuania's eastern edge.

In the north, the Livonian War was fought over Livonia. This region was important for trade. The Livonian Confederation allied with Poland-Lithuania in 1557. Livonia was then added to the Polish Crown by Sigismund II. This led Ivan the Terrible of Russia to attack Livonia in 1558. Later, he attacked Lithuania. Lithuania's fort of Polotsk fell in 1563. This was followed by a Lithuanian victory at the Battle of Ula in 1564. But Polotsk was not recovered. Livonia was divided by Russian, Swedish, and Polish-Lithuanian forces.

Moving Towards a More United State

Polish rulers wanted to fully join the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into Poland. Lithuanians managed to avoid this in the 14th and 15th centuries. But the power balance changed in the 16th century. In 1508, the Polish parliament voted money for Lithuania's defense against Moscow. The Polish nobility wanted a full union. This was because Lithuania relied more and more on Poland against Moscow. This problem grew worse under Sigismund II Augustus. He was the last Jagiellonian king and grand duke of Lithuania. He had no heir to continue the union.

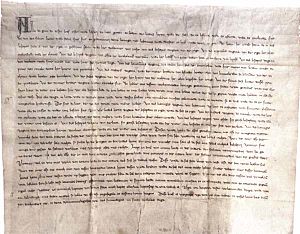

Lithuania's laws were changing. In 1563, Sigismund gave full political rights back to the Grand Duchy's Orthodox nobles. These rights had been limited by Vytautas. All nobles were now officially equal. Courts were set up in 1565–66. The Second Lithuanian Statute of 1566 created local offices like the Polish system. The Lithuanian assembly got the same powers as the Polish Sejm.

The Polish Sejm met in Lublin in January 1569. Lithuanian lords attended at Sigismund's request. Most left on March 1. They were unhappy with Polish proposals. Sigismund then announced that Volhynia and Podlasie would join the Polish Crown. Soon, the large Kiev Voivodeship and Bratslav Voivodeship were also added. Ruthenian nobles in these areas mostly approved. This meant they would become part of the privileged Polish nobility. The king also pressured many deputies to agree to compromises. This led to the "voluntary" signing of the Union of Lublin on July 1. The new state would have a common parliament. But separate state offices would remain. Many Lithuanians did not like this. But they decided to comply. Sigismund managed to keep the Polish-Lithuanian state as a great power.

Lithuanian Renaissance

From the 16th to the mid-17th century, culture, arts, and education grew in Lithuania. This was thanks to the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. Lutheran ideas entered Livonia by the 1520s. Lutheranism soon became the main religion in Livonian cities. Lithuania stayed Catholic.

An important book dealer was Francysk Skaryna (around 1485—1540). He was a founder of Belarusian writing. He wrote in his native Ruthenian language. This was common for writers in the early Renaissance in Lithuania. After the mid-16th century, Polish became the main language for books. Many educated Lithuanians returned from studying abroad. They helped build the active cultural life of 16th-century Lithuania. This time is sometimes called the Lithuanian Renaissance.

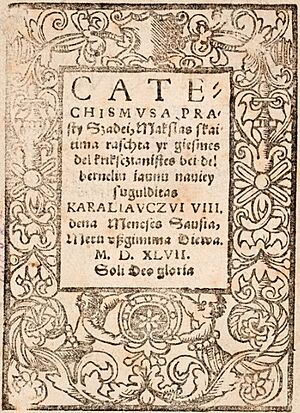

Italian architecture came to Lithuanian cities. Lithuanian literature written in Latin grew. Also, the first printed books in the Lithuanian language appeared. The written Lithuanian language began to form. Scholars like Abraomas Kulvietis, Stanislovas Rapalionis, Martynas Mažvydas, and Mikalojus Daukša led this process.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795)

A New Union with Poland

With the Union of Lublin in 1569, Poland and Lithuania formed a new state. It was called the Republic of Both Nations, or commonly, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. This Commonwealth was ruled by Polish and Lithuanian nobles. They also elected their kings. The Union aimed for a common foreign policy, customs, and money. Poland and Lithuania kept separate armies. But they set up similar government offices. The Lithuanian Tribunal, a high court for nobles, was created in 1581.

Languages in the Commonwealth

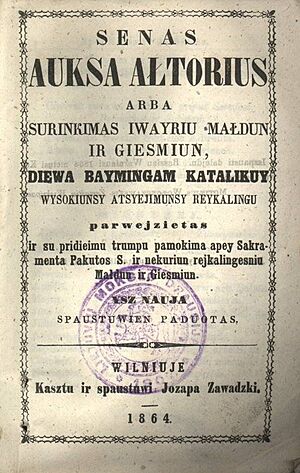

The Lithuanian language was used less in the grand ducal court by the late 15th century. Polish became more popular. A century later, Polish was common even among ordinary Lithuanian nobles. After the Union of Lublin, Polish culture and language increasingly affected Lithuanian public life. But it took over a century for this to be complete. The 1588 Statutes of Lithuania were still written in the Ruthenian Chancery Slavonic language. From about 1700, Polish was used in official documents.

The Lithuanian nobility became Polish in language and culture. But they still felt a sense of Lithuanian identity. The Lithuanian language survived as a peasant language. It also appeared in written religious texts from 1547.

Western Lithuania was important for keeping the Lithuanian language and culture alive. In Samogitia, many nobles continued to speak Lithuanian. Northeastern East Prussia, sometimes called Lithuania Minor, had many Lithuanians. They were mostly Lutheran. Lutherans encouraged printing religious books in local languages. This is why Martynas Mažvydas' Catechism was printed in 1547 in East Prussian Königsberg.

Religion in the Commonwealth

Most of the East Slavic people in the Grand Duchy were Eastern Orthodox. Many Lithuanian nobles also remained Orthodox. Around the time of the Union of Lublin in 1569, many nobles converted to Western Christianity. After the Protestant Reformation, many noble families became Calvinists in the 1550s and 1560s. A generation later, many became Roman Catholic.

In the early Commonwealth, religious tolerance was normal. It was officially made law by the Warsaw Confederation in 1573.

By 1750, about 80% of the Commonwealth's people were Catholic. This included most nobles and all lawmakers. In the east, there were also Orthodox Christians. But Catholics in the Grand Duchy were split. Less than half were Latin rite (loyal to Rome). The others were mostly non-noble Ruthenians who followed the Eastern rite. They were called Uniates. Their church was set up at the Union of Brest in 1596. They only nominally obeyed Rome.

Grand Duchy: Rise and Fall

Even with the Union of Lublin, Lithuania continued as a grand duchy within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth for over two centuries. It kept its own laws, army, and treasury. When the Union of Lublin happened, King Sigismund II Augustus took Ukraine and other lands from Lithuania. He added them directly to the Polish Crown. The grand duchy was left with today's Belarus and parts of European Russia, plus the core Lithuanian lands.

From 1573, the kings of Poland and grand dukes of Lithuania were always the same person. They were elected by the nobility. The nobles gained more and more privileges. This led to a unique system called the Golden Liberty. These privileges, especially the liberum veto (where one noble could stop any law), caused political chaos. This eventually led to the state's end.

Within the Commonwealth, the grand duchy helped Europe in many ways. Western Europe got grain through the Danzig to Amsterdam sea route. The Commonwealth's religious tolerance and democracy among nobles were unique. Vilnius was a capital where Western and Eastern Christianity met. Many religions were practiced there. To Jews, it was the "Jerusalem of the North." Vilnius University was a major learning center. The Vilnius school greatly contributed to European Baroque architecture. Lithuanian law created advanced legal codes called the Statutes of Lithuania. At the end of the Commonwealth, the Constitution of 3 May 1791 was the first written constitution in Europe.

The Commonwealth was greatly weakened by many wars. This started with the Khmelnytsky Uprising in Ukraine in 1648. During the Northern Wars of 1655–1661, the Swedish army devastated Lithuania. This event was known as the Deluge. Vilnius was burned and looted by Russian forces. Before it could recover, Lithuania was again damaged during the Great Northern War of 1700–1721.

Besides war, the Commonwealth suffered from plague and famine. These disasters caused about 40% of the country's people to die. Foreign powers, especially Russia, became very powerful in the Commonwealth's politics. Many noble groups, controlled by powerful nobles, used their "Golden Liberty" to stop reforms.

The Constitution of 3 May 1791 was a late attempt to reform the Commonwealth. It tried to bring Lithuania and Poland closer. But the separation was kept by the Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations. The partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772, 1793, and 1795 ended its existence. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was divided. The Russian Empire took over 90% of its land. The Kingdom of Prussia took the rest. The Third Partition of 1795 happened after the Kościuszko Uprising failed. This was the last war by Poles and Lithuanians to save their state. Lithuania stopped existing as a separate country for over a century.

Under Russian Rule and World War I (1795–1918)

After the Commonwealth (1795–1864)

After the partitions, the Russian Empire controlled most of Lithuania. This included Vilnius. In 1803, Tsar Alexander I reopened Vilnius University. It became the largest university in the Russian Empire. In the early 1800s, it seemed Lithuania might get some special recognition. But this never happened.

In 1812, Lithuanians welcomed Napoleon Bonaparte's army. Many joined the French invasion of Russia. After Napoleon's defeat, Tsar Alexander I kept Vilnius University open. The Polish-language poet Adam Mickiewicz studied there. Part of Lithuania that Prussia took in 1795 became part of the Russian-controlled Kingdom of Poland in 1815. The rest of Lithuania remained a Russian province.

Poles and Lithuanians rebelled against Russian rule twice. These were in 1830-31 (the November Uprising) and 1863–64 (the January Uprising). Both failed. This led to more harsh rule by Russia. After the November Uprising, Tsar Nicholas I started a strong program to make people more Russian. Vilnius University was closed. Lithuania became part of a new region called the Northwestern Krai. Despite the harsh rule, Polish schooling and culture continued in Lithuania. The Statutes of Lithuania were canceled by Russia only in 1840. Serfdom (where farmers were tied to the land) was ended in 1861.

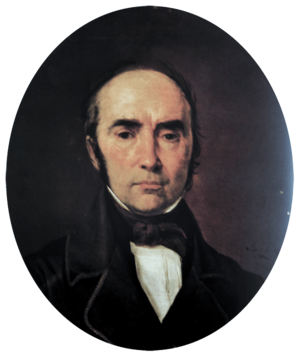

The Polish poetry of Adam Mickiewicz influenced the new Lithuanian national movement. Simonas Daukantas, who studied with Mickiewicz, wanted to return to Lithuania's old traditions. He wanted to renew the local culture based on the Lithuanian language. He wrote a history of Lithuania in Lithuanian in 1822. Teodor Narbutt wrote a long Ancient History of the Lithuanian Nation (1835–1841) in Polish. He also talked about historic Lithuania's glory days. By the mid-19th century, the idea of a future Lithuanian nationalist movement was clear. It focused on language identity. To create a modern Lithuanian identity, it needed to break away from Polish culture and language.

Around the January Uprising, there was a generation of Lithuanian leaders. They were a bridge between a Polish-linked political movement and the modern Lithuanian nationalist movement. They wanted to ally with local farmers. These farmers, if given land, would help defeat Russia. This led to new ideas about how a nation is formed.

Building a Modern Identity (1864–1918)

The failure of the January Uprising in 1864 made the link with Poland seem old-fashioned to many Lithuanians. It also created a group of free and often rich farmers. Unlike city people, who often spoke Polish, these farmers kept the Lithuanian language alive. More education became available to young people from common backgrounds. This was a key factor for the Lithuanian national revival. Schools were becoming less Polish. Lithuanian university students were sent to Saint Petersburg or Moscow instead of Warsaw. This created a cultural gap. Russian attempts to make people more Russian did not fill this gap.

Russian nationalists saw the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania as Russian. They believed these lands should be "reunited" with Russia. But in the following decades, a Lithuanian national movement appeared. It included people from different backgrounds. Many spoke Polish, but they all wanted to promote Lithuanian culture and language. This was their way to build a modern nation. This movement no longer aimed to bring back the old Grand Duchy. Its goals were limited to lands they saw as historically Lithuanian.

In 1864, the Lithuanian language and the Latin alphabet were banned in schools. Printing in Lithuanian was also forbidden. This was part of Russia's policy to restore what they saw as Russian roots in Lithuania. The Russian authorities put in place many policies to make people more Russian. These included a Lithuanian press ban and closing cultural and educational places. Lithuanians resisted this. Bishop Motiejus Valančius led some of this resistance. Lithuanians arranged for books to be printed abroad. They then smuggled these books into the country from nearby East Prussia.

Lithuanian was not seen as an important language. Many thought it would die out. More and more areas in the east became Slavic. More people used Polish or Russian daily. The only place where Lithuanian was seen as important was in East Prussia. This area was sometimes called "Lithuania Minor" by Lithuanian nationalists. At that time, northeastern East Prussia had many ethnic Lithuanians. But even there, German influence threatened their culture.

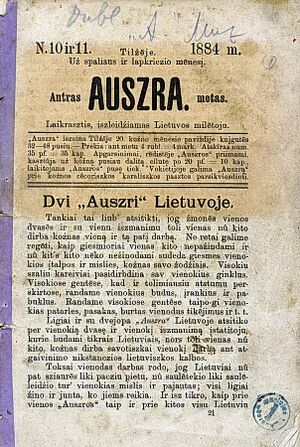

The language revival spread to richer groups. It started with Lithuanian newspapers like Aušra and Varpas. Then, poems and books were written in Lithuanian. Many of these praised the historic Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

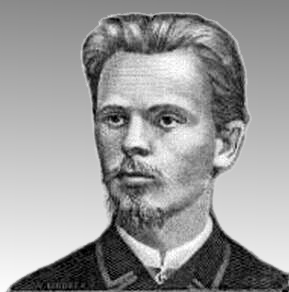

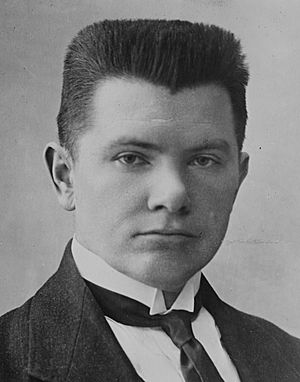

The two most important figures in the revival were Jonas Basanavičius and Vincas Kudirka. Both came from rich Lithuanian farming families. They went to the Marijampolė Gymnasium (secondary school). This school was a Polish education center. It became more Russian after the January Uprising. Lithuanian language classes were introduced there at that time.

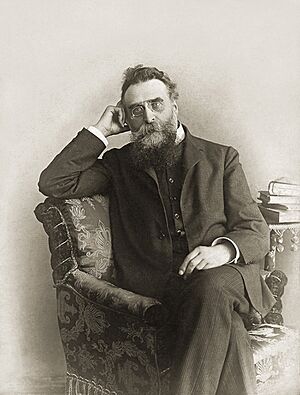

Basanavičius studied medicine at Moscow State University. He made international connections there. He published works on Lithuanian history (in Polish). He graduated in 1879. From Moscow, he went to Bulgaria. In 1882, he moved to Prague. In Prague, he was influenced by the Czech National Revival movement. In 1883, Basanavičius started a Lithuanian language review. It became a newspaper called Aušra (The Dawn). It was published in Ragnit, Prussia. Aušra was printed in Latin letters, which were banned under Russian law. Russian law required the Cyrillic alphabet for Lithuanian printing. The newspaper was smuggled into Lithuania. It helped show links to the medieval Grand Duchy and praised the Lithuanian people.

Russian rules at Marijampolė school were eased in 1872. Kudirka learned Polish there. He then studied at the University of Warsaw. There, he was influenced by Polish socialists. In 1889, Kudirka returned to Lithuania. He worked to bring Lithuanian farmers into politics. He saw them as the main part of a modern nation. In 1898, he wrote a poem. It was inspired by a famous Polish poem. His poem became the national anthem of Lithuania, Tautiška giesmė: ("Lithuania, Our Homeland").

As the revival grew, Russian policy became harsher. Catholic churches were attacked. The ban on Lithuanian printing continued. But in the late 19th century, the language ban was lifted. About 2,500 books were published in the Lithuanian Latin alphabet. Most were published in Tilsit, Prussia. Some came from the United States. By 1900, a mostly standard written language was achieved. It was based on old and Aukštaitijan (highland) uses. The letters -č-, -š-, and -v- were taken from modern Czech spelling. This avoided Polish spelling for similar sounds. The widely accepted Lithuanian Grammar, by Jonas Jablonskis, appeared in 1901.

Many Lithuanians moved to the United States in 1867–1868 after a famine. Between 1868 and 1914, about 635,000 people left Lithuania. This was almost 20 percent of the population. Lithuanian cities and towns grew under Russian rule. But the country remained undeveloped. Job opportunities were limited. Many Lithuanians also left for industrial cities in Russia, like Riga and Saint Petersburg. Many Lithuanian cities were dominated by non-Lithuanian-speaking Jews and Poles.

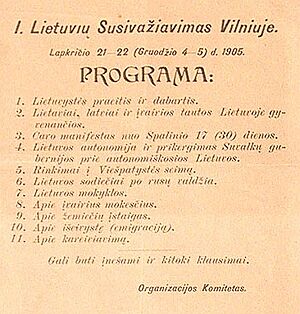

Lithuania's nationalist movement continued to grow. During the 1905 Russian Revolution, a large meeting of Lithuanian representatives took place in Vilnius. This was called the Great Seimas of Vilnius. On December 5, 1905, they demanded self-rule for Lithuania. The Russian government made some changes because of the 1905 uprising. The Baltic states were again allowed to use their native languages in schools and public talks. Catholic churches were built in Lithuania. Latin letters replaced the Cyrillic alphabet. But even Russian liberals did not want to give Lithuania as much self-rule as Estonia and Latvia had.

After Russia entered World War I, the German Empire occupied Lithuania and Courland in 1915. Vilnius fell to the German army on September 19, 1915. Lithuania was put under a German government called Ober Ost. The Germans planned to create formally independent states that would actually depend on Germany.

Lithuanian Independence (1918–1940)

Declaration of Independence

The German occupation government allowed a Vilnius Conference to meet in September 1917. The Germans wanted Lithuanians to declare loyalty to Germany. The conference wanted to start creating a Lithuanian state. This state would be based on ethnic identity and language. It would be independent from Russia, Poland, and Germany. The conference elected a 20-member Council of Lithuania (Taryba). This council was to act as the main authority for the Lithuanian people. The Council, led by Jonas Basanavičius, declared Lithuanian independence as a German protectorate on December 11, 1917. Then, they adopted the full Act of Independence of Lithuania on February 16, 1918. It said Lithuania was an independent republic with democratic rules. The Germans did not support this. They tried to stop real independence. To avoid being part of Germany, Lithuanians chose King Mindaugas II as the king of the Kingdom of Lithuania in July 1918. But Mindaugas II never took the throne.

Meanwhile, there was also an attempt to bring back the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. This would be a socialist, multi-national republic under German occupation. In March 1918, Anton Luckievich and his Belarusian National Council declared a Belarusian People's Republic. It was supposed to include Vilnius. Luckievich and the Council fled from the Red Army. When they arrived in Vilnius, they suggested a Belarusian-Lithuanian federation. But Lithuanian leaders were not interested. They were focused on their own national plans.

A Belarusian unit was formed within the Lithuanian Armed Forces in 1919. It was called the 1st Belarusian Regiment. This unit helped Lithuania during the Lithuanian Wars of Independence. Many members received Lithuania's highest award. Also, a Lithuanian Ministry for Belarusian Affairs was set up. It worked from 1918–1924. Ethnic Belarusians were also part of the Council of Lithuania.

Germany lost World War I. It signed the Armistice of Compiègne on November 11, 1918. Lithuanians quickly formed their first government. They adopted a temporary constitution. They started setting up basic government structures. The first prime minister was Augustinas Voldemaras. As the German army left, Soviet forces followed. They wanted to spread a global revolution. They created several puppet states. One was the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic on December 16, 1918. By late December, the Red Army reached Lithuania. The Lithuanian–Soviet War began.

On January 1, 1919, the German army left Vilnius. They gave the city to local Polish defense forces. The Lithuanian government moved to Kaunas. Kaunas became the temporary capital of Lithuania. The Soviet Red Army captured Vilnius on January 5, 1919. Since the Lithuanian army was new, the Soviets moved easily. By mid-January 1919, they controlled about two-thirds of Lithuania. Vilnius became the capital of the Lithuanian Soviet Republic. Soon, it was the capital of the combined Lithuanian–Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.

From April 1919, the Lithuanian–Soviet War continued alongside the Polish–Soviet War. Polish troops captured Vilnius from the Soviets on April 21, 1919. Poland had claims over Lithuania, especially the Vilnius Region. These tensions led to the Polish–Lithuanian War. Józef Piłsudski of Poland wanted a Polish-Lithuanian federation. But he could not agree with Lithuanian politicians. In August 1919, he tried to overthrow the Lithuanian government in Kaunas.

The Belarusian unit of the Lithuanian Armed Forces in Grodno was disbanded by the Poles in April 1919. Its soldiers were disarmed and humiliated. They refused Polish orders and stayed loyal to Lithuania. After Grodno was taken, Lithuanian and Belarusian flags were torn down. Polish flags were raised instead. Some Belarusian soldiers escaped to Kaunas and continued serving Lithuania.

The Lithuanian Army, led by General Silvestras Žukauskas, stopped the Red Army near Kėdainiai. In spring 1919, Lithuanians recaptured several towns. By late August 1919, the Soviets were pushed out of Lithuania. The Lithuanian Army then fought the West Russian Volunteer Army (Bermontians). These forces invaded northern Lithuania. They were defeated by late 1919. This ended the first part of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence. Lithuanians could then focus on internal matters.

Democratic Period

The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania was elected in April 1920. It first met in May. In June, it adopted a temporary constitution. On July 12, 1920, it signed the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty. In this treaty, the Soviet Union recognized independent Lithuania. It also recognized Lithuania's claims to the Vilnius Region. Lithuania secretly allowed Soviet forces to pass through its land to fight Poland. On July 14, 1920, the Soviet army captured Vilnius again from Polish forces. The city was given back to Lithuanians on August 26, 1920.

The victorious Polish army returned. The Soviet–Lithuanian Treaty increased tensions between Poland and Lithuania. To stop more fighting, the Suwałki Agreement was signed with Poland on October 7, 1920. It left Vilnius on the Lithuanian side. But it never took effect. Polish General Lucjan Żeligowski, following orders from Józef Piłsudski, staged a fake rebellion. He invaded Lithuania on October 8, 1920. He captured Vilnius the next day. He set up a short-lived Republic of Central Lithuania on October 12, 1920.

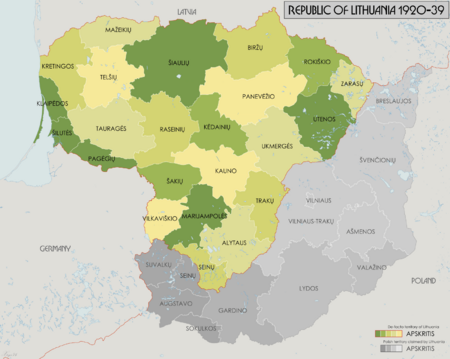

For 19 years, Kaunas was the temporary capital of Lithuania. The Vilnius region remained under Polish control. The League of Nations tried to help solve the dispute. But talks failed. Central Lithuania held an election in 1922. Jews, Lithuanians, and Belarusians boycotted it. Then, it was added to Poland on March 24, 1922. The Conference of Ambassadors gave Vilnius to Poland in March 1923. Lithuania did not accept this. It broke all ties with Poland. The two countries were officially at war over Vilnius. This lasted from 1920 to 1938. The dispute dominated Lithuanian politics.

The Constituent Assembly started many reforms. Lithuania gained international recognition. It became a member of the League of Nations. It passed a law for land reform. It introduced its own money, the litas. It adopted a final constitution in August 1922. Lithuania became a democratic state. The Seimas (parliament) was elected by men and women for three years. The Seimas elected the president. The First Seimas of Lithuania was elected in October 1922. But it could not form a government. It was forced to dissolve. Its only lasting achievement was the Klaipėda Revolt in January 1923.

Lithuania took advantage of the Ruhr Crisis in Europe. It captured the Klaipėda Region. This area was separated from East Prussia after World War I. It was under French control. The region was made an autonomous district of Lithuania in May 1924. This gave Lithuania its only access to the Baltic Sea. It was also an important industrial center. But the region's many German people resisted Lithuanian rule in the 1930s. The Klaipėda Revolt was the last armed conflict in Lithuania before World War II.

The Second Seimas of Lithuania, elected in May 1923, was the only one to serve its full term. It continued land reform. It started social support systems. It began repaying foreign debt. The first Lithuanian national census happened in 1923.

Authoritarian Period

The Third Seimas of Lithuania was elected in May 1926. For the first time, the Christian Democratic Party lost its majority. It was criticized for signing a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union. It was accused of making Lithuania too "Bolshevik." As tensions grew, the government was overthrown in a coup in December. The military organized the coup. It was supported by the Lithuanian Nationalists Union and Christian Democrats. They made Antanas Smetona president and Augustinas Voldemaras prime minister. Smetona stopped opposition and remained an authoritarian leader until June 1940.

The Seimas thought the coup was temporary. They expected new elections. But the parliament was dissolved in May 1927. Later that year, Social Democrats tried to rebel against Smetona. But they were quickly stopped. Voldemaras became too independent. He was forced to resign in 1929. Smetona announced a new constitution in May 1928 without consulting the Seimas. This constitution greatly increased the president's powers. Smetona's party grew in size. He took the title "tautos vadas" (leader of the nation). He slowly built a cult of personality.

When the Nazi Party came to power in Germany, relations with Lithuania worsened. The Nazis did not accept losing the Klaipėda Region. They supported anti-Lithuanian groups there. In 1934, Lithuania put activists on trial. About 100 people were sentenced to prison. This led Germany to stop buying Lithuanian products. Lithuania then shifted its exports to the United Kingdom. Smetona's reputation was damaged. In September 1936, he agreed to call elections for the Seimas. Before the elections, all parties except the National Union were removed. So, 42 of 49 members were from the National Union. This assembly advised the president. In February 1938, it adopted a new constitution. This gave the president even more power.

As tensions rose in Europe, Poland gave Lithuania an ultimatum in March 1938. Poland demanded normal diplomatic relations. It threatened military action if Lithuania refused. Lithuania had a weaker military. It could not get international support. So, it accepted the ultimatum. Relations became somewhat normal. Treaties were made about railways and mail.

Lithuania supported Germany and the Soviet Union against countries that backed Poland. But both Germany and the Soviet Union still took Lithuanian land. On March 20, 1939, Lithuania received an ultimatum from Germany. It demanded the immediate transfer of the Klaipėda Region to Germany. The Lithuanian government accepted to avoid war. The Klaipėda Region became part of Germany. This caused a political crisis in Lithuania. Smetona had to form a new government with opposition members. Losing Klaipėda greatly hurt Lithuania's economy. The country moved into Germany's influence.

Adolf Hitler first planned to make Lithuania a satellite state. It would help in his military conquests for more land. But Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939. They divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence. Lithuania was first assigned to Germany. But this changed after Smetona refused to join the German invasion of Poland. Joseph Stalin agreed to give Poland's areas to Germany. In return, Lithuania would enter the Soviet sphere.

The time of independence between the wars saw the growth of Lithuanian press, literature, music, and arts. A full education system with Lithuanian as the teaching language was built. Schools expanded. Universities were set up in Kaunas. Lithuanian society remained mostly agricultural. Only 20% of people lived in cities. The Catholic Church was strong. Birth rates were high. The population grew by 22% between 1923–1939, despite people moving abroad.

In almost all cities, Lithuanians became the majority. Before, these cities were mostly Jewish, Polish, Russian, and German. For example, Lithuanians were 59% of Kaunas residents in 1923, compared to 7% in 1897. The right-wing rule from 1926–1940 had a strange stabilizing effect. It prevented the worst anti-Jewish actions. It also stopped the rise of extreme political groups.

World War II (1939–1945)

First Soviet Occupation

Secret parts of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, changed by the German-Soviet Frontier Treaty, divided Eastern Europe. The three Baltic states fell into the Soviet area. During the invasion of Poland, the Red Army captured Vilnius. Lithuanians saw Vilnius as their capital. According to the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Pact of October 10, 1939, the Soviet Union gave Vilnius and nearby land to Lithuania. In return, 20,000 Soviet troops were stationed in Lithuania. This was almost giving up independence. Similar pacts were signed with Latvia and Estonia.

In spring 1940, the Soviets increased pressure on Lithuania. They gave Lithuania an ultimatum on June 14. It demanded a new pro-Soviet government. It also demanded allowing more Red Army troops. With Soviet troops already there, Lithuania could not resist. It accepted the ultimatum. President Antanas Smetona fled. 150,000 Soviet troops crossed the border. Soviet official Vladimir Dekanozov formed a new pro-Soviet government. It was called the People's Government of Lithuania. It was led by Justas Paleckis. They organized fake elections for the "People's Seimas." On July 21, this Seimas voted to make Lithuania the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic. It asked to join the Soviet Union. This was approved on August 3, 1940. This officially completed the takeover.

After the occupation, Soviet authorities quickly started making Lithuania more Soviet. All land was taken by the state. To get support, large farms were given to small landowners. But taxes on farms were greatly increased. This was to make farmers go bankrupt for future collectivization. Banks, large businesses, and real estate were taken by the state. This caused shortages of goods. The Lithuanian litas currency was made artificially low. It was removed by spring 1941. Living standards dropped. All religious, cultural, and political groups were banned. Only the Communist Party and its youth branch remained. About 12,000 "enemies of the people" were arrested. In June 1941, about 12,600 people were sent to Gulags in Siberia. These were mostly former military officers, police, politicians, and their families. Many died in bad conditions.

Nazi German Occupation (1941–1944)

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. This was called Operation Barbarossa. German forces moved quickly. They met little Soviet resistance. Vilnius was captured on June 24, 1941. Germany controlled all of Lithuania within a week. The retreating Soviet forces killed between 1,000 and 1,500 people. Lithuanians generally welcomed the Germans. They hoped Germany would give their country some self-rule. The Lithuanian Activist Front organized an anti-Soviet revolt. It declared independence. It formed a Provisional Government of Lithuania. The Provisional Government was not forced to dissolve. But the Germans took away its power. It resigned on August 5, 1941. Germany set up a civil administration called the Reichskommissariat Ostland.

At first, some Lithuanians worked with the Germans. Lithuanians joined police units. They hoped these units would become a regular army for independent Lithuania. Instead, some units were used by the Germans to help with the Holocaust. But Lithuanians soon became unhappy with harsh German policies. Germans took war supplies. They forced people to work in Germany. They drafted men into the army. And they did not give real self-rule. This led to a resistance movement. The most important group was the Supreme Committee for the Liberation of Lithuania. It formed in 1943. Lithuanians did not organize armed resistance. They still saw the Soviet Union as their main enemy. Armed resistance was carried out by pro-Soviet groups and Polish forces in eastern Lithuania.

Before the Holocaust, Lithuania had many Jews. About 90% or more of the Lithuanian Jews were murdered. This was one of the highest rates in Europe. The Holocaust in Lithuania happened in three stages. First, mass killings (June–December 1941). Second, a ghetto period (1942 – March 1943). Third, a final liquidation (April 1943 – July 1944). Killings started on the first days of German occupation. They were done by Nazis and their Lithuanian helpers. About 80% of Lithuanian Jews were killed before 1942. The remaining 43,000 Jews were put in ghettos. They were forced to work for German industry. In 1943, the ghettos were destroyed or turned into concentration camps. Only about 2,000–3,000 Lithuanian Jews were freed from these camps. More survived by fleeing to Russia or joining Jewish resistance groups.

Second Soviet Occupation

In summer 1944, the Soviet Red Army reached eastern Lithuania. By July 1944, the area around Vilnius was controlled by Polish resistance fighters. The Red Army captured Vilnius with Polish help on July 13. The Soviet Union re-occupied Lithuania. Joseph Stalin re-established the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1944. Its capital was Vilnius. The Soviets got the quiet agreement of the United States and Great Britain for this takeover. By January 1945, Soviet forces captured Klaipėda. The worst losses in Lithuania during World War II happened in 1944–1945. This was when the Red Army pushed out the Nazis. It is thought that Lithuania lost 780,000 people between 1940 and 1954. This was under Nazi and Soviet rule.

Soviet Period (1944–1990)

Stalinist Terror and Resistance (1944–1953)

The Soviet deportations from Lithuania between 1941 and 1952 sent thousands of families into exile. They were sent to forced settlements in the Soviet Union, especially in Siberia. Between 1944 and 1953, almost 120,000 people (5% of the population) were deported. Thousands more became political prisoners. Many important thinkers and most Catholic priests were deported. Many returned after 1953. About 20,000 Lithuanian partisans fought unsuccessfully against the Soviet rule in the 1940s and early 1950s. Most were killed or sent to Siberian labor camps. More Lithuanians died after World War II than during it.

Lithuanian armed resistance lasted until 1953. Adolfas Ramanauskas, the last official commander of the Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters, was arrested in 1956 and executed in 1957.

Soviet Era (1953–1988)

Soviet authorities encouraged non-Lithuanian workers to move to Lithuania. This was to integrate Lithuania into the Soviet Union. It also aimed to develop industry. But this did not happen on a large scale in Lithuania, unlike other Soviet republics.

To a great extent, Lithuanian culture grew stronger, not weaker, in postwar Vilnius. Elements of a national revival happened during Lithuania's time as a Soviet republic. Lithuania's borders were set by Joseph Stalin. He decided to give Vilnius to the Lithuanian SSR again in 1944. Later, most Poles were moved out of Vilnius. They were partly replaced by Russian immigrants. Vilnius then became more Lithuanian in population and culture. This fulfilled a long-held dream of Lithuanian nationalists. Lithuania's economy did well compared to other parts of the Soviet Union.

National developments in Lithuania followed quiet agreements. These were made by Soviet communists, Lithuanian communists, and Lithuanian thinkers. Vilnius University reopened after the war. It taught in Lithuanian and had mostly Lithuanian students. It became a center for Baltic studies. Schools in the Lithuanian SSR taught more in Lithuanian than ever before. The written Lithuanian language was standardized. It became more refined for scholarship and literature.

Between Stalin's death in 1953 and the reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev in the mid-1980s, Lithuania was a Soviet society. It had all its repressions and unique features. Farming remained collective. Property was owned by the state. Criticism of the Soviet system was severely punished. The country was mostly cut off from the non-Soviet world. The Catholic Church was persecuted. Society was officially equal, but it had a lot of corruption. People who served the system got special connections and privileges.

The communist era is shown in the museum at Grūtas Park.

Rebirth (1988–1990)

Until mid-1988, the Communist Party of Lithuania (CPL) controlled all political, economic, and cultural life. Lithuanians, like people in other Baltic republics, did not trust the Soviet regime. They strongly supported Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms, called perestroika and glasnost. A group of thinkers formed the Reform Movement of Lithuania, Sąjūdis, in mid-1988. It called for democratic and national rights. It became very popular.

Inspired by Sąjūdis, the Supreme Soviet of the Lithuanian SSR changed the constitution. Lithuanian laws became more important than Soviet laws. They canceled the 1940 decisions that made Lithuania part of the Soviet Union. They made a multi-party system legal. They also brought back national symbols: the flag of Lithuania and the national anthem. Many CPL members also supported Sąjūdis. With Sąjūdis' help, Algirdas Brazauskas was elected First Secretary of the CPL in 1988.

On August 23, 1989, 50 years after the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Latvians, Lithuanians, and Estonians formed a human chain. It stretched 600 kilometers from Tallinn to Vilnius. This was to show the world the fate of the Baltic nations. It was called the Baltic Way. In December 1989, the CPL, led by Brazauskas, declared independence from the Soviet Communist Party. It became a separate social democratic party. In 1990, it renamed itself the Democratic Labour Party of Lithuania.

Independence Restored (1990–Present)

Fight for Independence (1990–1991)

In early 1990, candidates supported by Sąjūdis won the Lithuanian parliamentary elections. On March 11, 1990, the Supreme Soviet of the Lithuanian SSR declared the Act of the Re-Establishment of the State of Lithuania. Lithuania was the first Soviet republic to declare independence. Vytautas Landsbergis, a Sąjūdis leader, became head of state. Kazimira Prunskienė led the government. Temporary basic laws for the state were passed.

On March 15, the Soviet Union demanded that Lithuania cancel its independence. It started using political and economic pressure. On April 18, Soviets blocked Lithuania economically. This lasted until late June. The Soviet military took over some public buildings. But violence was mostly avoided until January 1991. During the January Events in Lithuania, Soviet authorities tried to overthrow the elected government. They took over the Vilnius TV Tower. They killed 14 unarmed people and injured 140. During this attack, an amateur radio station helped contact the outside world. Moscow did not try to crush the independence movement further. The Lithuanian government continued to work.

On February 9, 1991, a national vote was held. More than 90% of those who voted (76% of all eligible voters) wanted an independent, democratic Lithuania. During the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt in August, Soviet troops took over some government buildings. But they returned to their barracks when the coup failed. The Lithuanian government banned the Soviet Communist Party. After the failed coup, Lithuania gained wide international recognition on September 6, 1991. It joined the United Nations on September 17.

Modern Republic of Lithuania (1991–Present)

Like in many former Soviet countries, the popularity of the independence movement (Sąjūdis) decreased. This was because of a worsening economy. The Communist Party of Lithuania renamed itself the Democratic Labour Party of Lithuania (LDDP). It won most seats in the 1992 elections. The LDDP continued building an independent democratic state. It also moved from a planned economy to a free market economy. In the 1996 elections, voters swung back to the right-wing Homeland Union. This party was led by former Sąjūdis leader Vytautas Landsbergis.

To change to capitalism, Lithuania started a privatization campaign. It sold government-owned homes and businesses. The government gave out investment vouchers instead of money. People worked together to collect more vouchers for auctions. Lithuania did not create a small group of very rich people, unlike Russia. Privatization started with small businesses. Large companies were sold later for hard currency to attract foreign investors. Lithuania's money system was based on the Lithuanian litas. This currency was used before the war. Because of high inflation, a temporary currency was used first. The litas was finally issued in June 1993. It was set to a fixed exchange rate with the United States dollar in 1994 and the Euro in 2002.

Even after independence, many Russian Armed Forces troops stayed in Lithuania. Getting these troops to leave was a top priority. Russian troops left by August 31, 1993. The first military of the reborn country was the Lithuanian National Defence Volunteer Forces. They took an oath soon after independence. The Lithuanian military built itself to common standards. This included the Lithuanian Air Force, Lithuanian Naval Force, and Lithuanian Land Force. Old groups like the Lithuanian Riflemen's Union were re-established.

On April 27, 1993, a partnership with the Pennsylvania National Guard was created.

Lithuania wanted closer ties with the West. It applied for NATO membership in 1994. The country had to make a difficult change from a planned economy to a free market. This was to meet the requirements for European Union (EU) membership. In May 2001, Lithuania became the 141st member of the World Trade Organization. In October 2002, Lithuania was invited to join the European Union. One month later, it was invited to join NATO. It became a member of both in 2004.

Because of the global financial crisis, Lithuania's economy had its worst recession since 1991. After a growth boom from joining the EU, the economy shrank by 15% in 2009. Since joining the EU, many Lithuanians (up to 20% of the population) have moved abroad. They seek better jobs. This is a big problem for the small country. On January 1, 2015, Lithuania joined the eurozone. It adopted the Euro as its currency. On July 4, 2018, Lithuania officially joined OECD.

Dalia Grybauskaitė (2009–2019) was the first female President of Lithuania. She was also the first president to be re-elected for a second term.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Lituania para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Lituania para niños

- History of Vilnius

- List of hillforts in Lithuania

- List of rulers of Lithuania

- Northern Crusades

- Prime Minister of Lithuania

- Politics of Lithuania

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |