History of the Philippines (1898–1946) facts for kids

The history of the Philippines from 1898 to 1946 is called the American colonial period. This time began when the Spanish–American War started in April 1898. Back then, the Philippines was a colony of Spain. The period ended when the United States officially recognized the independence of the Republic of the Philippines on July 4, 1946.

After the Treaty of Paris (1898) was signed on December 10, 1898, Spain gave the Philippines to the United States. The first U.S. military government in the Philippines faced a lot of political trouble, including the Philippine–American War.

In 1906, a civilian government, called the Insular Government of the Philippine Islands, took over from the military government. William Howard Taft was its first governor-general. Before this, from 1898 to 1904, there were also Filipino revolutionary governments, but most countries didn't officially recognize them.

After the Tydings–McDuffie Act (also known as the Philippine Independence Act) was passed in 1934, an election was held in 1935. Manuel L. Quezon was elected and became the second president of the Philippines on November 15, 1935. The Insular Government ended, and the Commonwealth of the Philippines began. This was meant to be a temporary government, preparing the country for full independence in 1946.

Later, during World War II, Japan invaded and occupied the Philippines in 1941. The United States and the Philippine Commonwealth military fought back and took the Philippines again in 1945. After Japan surrendered, the U.S. officially recognized Philippine independence on July 4, 1946.

Contents

- Philippine Revolution and the Spanish–American War

- Philippine–American War (1899–1902)

- "Insular Government" (1900–1935)

- Philippine Commonwealth (1935–1946)

- Japanese Occupation and World War II (1941–1945)

- Independence (1946)

- World War II Veteran Benefits

- The U.S. Military in the Philippines Today

- See also

Philippine Revolution and the Spanish–American War

The Philippine Revolution started in August 1896. It ended with the Pact of Biak-na-Bato, a peace agreement signed on December 15, 1897. This agreement was between the Spanish governor-general Fernando Primo de Rivera and the revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo. The pact said that Aguinaldo and his fighters would give up their weapons. Other revolutionary leaders were given a pardon and money by the Spanish government. In return, the rebel government agreed to go into exile in Hong Kong.

The main reason for the Spanish–American War was that Spain did not make the social changes in Cuba that the United States wanted. U.S. President William McKinley gave Spain an ultimatum on April 19, 1898. Spain had no support from other European countries but still declared war. The U.S. declared war on April 25. Theodore Roosevelt, who was Assistant Secretary of the Navy, ordered Commodore George Dewey to take his ships to Hong Kong before the war started. From there, Dewey's ships left for the Philippines on April 27. They reached Manila Bay on the evening of April 30. The Battle of Manila Bay happened on May 1, 1898. The Americans won in just a few hours.

Dewey's quick victory made President McKinley decide to capture Manila from the Spanish. While waiting for more American troops, Dewey sent a ship to Hong Kong to bring Aguinaldo back to the Philippines. Aguinaldo arrived on May 19. After meeting with Dewey, he started revolutionary activities against the Spanish again. On May 24, Aguinaldo announced that he was taking command of all Philippine forces. He said he would set up a temporary government and would later step down for an elected president. Filipinos were very happy about Aguinaldo's return. Many Filipino soldiers left the Spanish army to join Aguinaldo. The Philippine Revolution against Spain started again, and Filipino forces captured many cities and provinces.

On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo declared the independence of the Philippines at his house in Cavite El Viejo. On June 18, Aguinaldo officially set up his temporary government. On June 23, he changed it to a revolutionary government and named himself president. By July 15, Aguinaldo had issued decrees to take civil control of the Philippines.

The first group of American troops arrived on June 30, led by General Thomas M. Anderson. Anderson asked Aguinaldo for help in fighting the Spanish. Aguinaldo thanked him but didn't agree to military cooperation. American generals thought Aguinaldo was trying to take Manila without their help. They also suspected he was limiting supplies to American forces and secretly talking with Spanish officials. Aguinaldo warned that American troops should not land in areas conquered by Filipinos without asking first. By June, U.S. and Filipino forces controlled most of the islands, except for the walled city of Intramuros. Admiral Dewey and General Merritt made a secret agreement with the Spanish governor-general, Fermín Jáudenes. They planned a fake battle where American forces would defeat the Spanish, but Filipino forces would not be allowed to enter the city.

On the evening of August 12, the Americans told Aguinaldo to stop his forces from entering Manila without American permission. On August 13, not knowing a peace agreement had been signed, U.S. forces began the Battle of Manila (1898) by attacking Spanish positions. Even though a fake battle was planned, Filipino fighters attacked on their own. This led to real fights with the Spanish, and some American soldiers were killed or wounded. The Spanish officially surrendered Manila to U.S. forces. Aguinaldo demanded that Filipino forces also occupy the city, but U.S. commanders insisted he withdraw his troops from Manila.

Peace Protocol Between the U.S. and Spain

On August 12, 1898, a peace agreement was signed in Washington between the U.S. and Spain. Part of this agreement said: "The United States will occupy and hold the City, Bay, and Harbor of Manila, until a peace treaty is made, which will decide the control, use, and government of the Philippines." General Merritt learned about this agreement on August 16, three days after Manila surrendered. Admiral Dewey and General Merritt were told by telegram on August 17 that the U.S. president wanted full control over Manila, with no shared occupation. After more talks, Filipino forces left the city on September 15. The Battle of Manila marked the end of cooperation between Filipinos and Americans.

On August 14, 1898, two days after Manila was captured, the U.S. set up a military government in the Philippines. General Wesley Merritt was the military governor. During military rule (1898–1902), the U.S. military commander governed the Philippines. When parts of the country became peaceful and under American control, responsibility was given to a civilian government. The military governor position ended in July 1902.

Under the military government, an American-style school system was started, with soldiers as the first teachers. Courts were also set up again, including a supreme court. Local governments were created in towns and provinces. The first local election was held on May 7, 1899, in Baliuag, Bulacan.

The Filipino revolutionary government held elections between June and September 10, 1898. This led to the creation of the Malolos Congress. From September 15 to November 13, 1898, the Malolos Constitution was adopted. It was made official on January 21, 1899, creating the First Philippine Republic with Emilio Aguinaldo as president.

At first, American peace negotiators with Spain were only told to ask for Luzon and Guam. These islands would be useful for harbors and communication. But President McKinley later sent new instructions to demand the entire group of islands. The Treaty of Paris (1898), signed in December 1898, officially ended the Spanish–American War. It stated that Spain would give the Philippines to the United States, and the U.S. would pay $20 million. This agreement was made clearer by the Treaty of Washington (1900). It said that any Spanish lands in the Philippines not mentioned in the Treaty of Paris were also given to the U.S.

On December 21, 1898, President McKinley announced a policy of "benevolent assimilation" for the Philippines. This was made public in the Philippines on January 4, 1899. Under this policy, the Philippines would come under U.S. rule. American forces were told to act as friends, not invaders.

Philippine–American War (1899–1902)

Rising Tensions and War

On December 21, 1898, President McKinley issued his "benevolent assimilation" announcement. General Otis delayed publishing it until January 4, 1899. He then published a changed version, removing words like "sovereignty" and "protection." Meanwhile, on December 26, 1898, the Spanish gave Iloilo to the Filipino rebels. American forces arriving in Iloilo were not allowed to land by the rebels, who said they needed "express orders from the central government of Luzon." Unknown to Otis, the U.S. War Department had also sent a copy of McKinley's original announcement to General Miller in Iloilo. Miller, not knowing a changed version was sent to Aguinaldo, published it in both Spanish and Tagalog. Even before Aguinaldo saw the original version and noticed the changes in the copy from Otis, he was upset that Otis had changed his own title to "Military Governor of the Philippines" from "...in the Philippines." Aguinaldo understood the importance of this change, which Otis made without permission from Washington.

On January 5, Aguinaldo issued his own statement. He listed American actions that went against their friendship and said that if Americans took over the Visayas, it would lead to fighting. Later that same day, Aguinaldo replaced this statement with another that directly protested American interference with "the sovereignty of these islands." Otis saw these statements as a call to war. As tensions grew, 40,000 Filipinos left Manila within 15 days. Meanwhile, Felipe Agoncillo, a Filipino diplomat, asked for a meeting with the U.S. president to discuss the Philippines. At the same time, Aguinaldo protested Otis calling himself "Military Governor of the Philippines." Filipino groups in London, Paris, and Madrid also told the U.S. that the Philippines would not accept American rule. Filipino forces were ready to fight, but they wanted the Americans to fire the first shot. On January 31, 1899, the Minister of Interior for the First Philippine Republic, Teodoro Sandiko, signed a decree. It said President Aguinaldo had ordered all unused lands to be planted to provide food, because war with the Americans was coming.

A shootout between a Filipino patrol and an American outpost on February 4 started open fighting between the two sides. On June 2, 1899, the First Philippine Republic officially declared war on the United States. Just like when they fought the Spanish, the Filipino rebels did not do well in open battles. Aguinaldo and his government escaped after Malolos was captured on March 31, 1899, and were forced into northern Luzon. Peace talks from some of Aguinaldo's cabinet members failed in May. The American commander, General Ewell Otis, demanded that Filipinos surrender without any conditions. In 1901, Aguinaldo was captured and swore loyalty to the United States, which marked a major end to the war.

Many more Filipinos died during the war than Americans. About 4,000 American soldiers died out of 125,000 who fought. Around 20,000 Filipino soldiers died, and between 250,000 and 1 million Filipino civilians also died.

First Philippine Commission

President McKinley appointed a group of five people on January 20, 1899. Their job was to study the situation in the islands and suggest what to do. The three civilian members of the Philippine Commission arrived in Manila on March 4, 1899. This was a month after the Battle of Manila, which started the armed conflict between U.S. and Filipino forces.

After meetings in April with Filipino representatives, the commission asked McKinley for permission to offer a plan. McKinley allowed them to offer a government with "a Governor-General appointed by the President; a cabinet appointed by the Governor-General; and a general advisory council elected by the people." The Filipino Congress voted to stop fighting and accept peace. On May 8, the Filipino cabinet led by Apolinario Mabini was replaced by a new "peace" cabinet led by Pedro Paterno. At this point, General Antonio Luna arrested Paterno and most of his cabinet, bringing Mabini and his cabinet back to power. After this, the commission decided that "...The Filipinos are completely unprepared for independence... there being no Philippine nation, but only a collection of different peoples." They suggested setting up a civilian government as quickly as possible. This included creating a two-house legislature, local governments in provinces and towns, and a system of free public elementary schools.

Second Philippine Commission

The Second Philippine Commission, also known as the Taft Commission, was appointed by McKinley on March 16, 1900. It was led by William Howard Taft. This commission had the power to make laws and some executive powers. On September 1, the Taft Commission started making laws. Between September 1900 and August 1902, it passed 499 laws. It set up a court system, including a supreme court, created a legal code, and organized a civil service. A law passed in 1901 allowed for elected presidents, vice presidents, and councilors in towns. These local officials were in charge of collecting taxes, maintaining public properties, and starting construction projects. They also elected provincial governors.

Establishment of Civil Government

On March 3, 1901, the U.S. Congress passed a law that gave the president the power to create a civil government in the Philippines. Before this, the president had been governing the Philippines using his war powers. On July 1, 1901, the civil government officially began with William H. Taft as the civil governor. Later, on February 3, 1903, the U.S. Congress changed his title to Governor-General.

A very organized public school system was started in 1901. English was used as the teaching language. This caused a big shortage of teachers. The Philippine Commission allowed the secretary of public instruction to bring 600 teachers from the U.S. These teachers were called the Thomasites. Free primary education, which taught people about citizenship and jobs, was put in place by the Taft Commission, following President McKinley's orders. Also, the Catholic Church was no longer the official state religion. A large amount of church land was bought and given back to the people.

A law against rebellion was made in 1901, followed by a law against banditry in 1902.

Official End to the War

The Philippine Organic Act (1902) of July 1902 approved the Philippine Commission. It also said that a two-house Philippine Legislature would be created. This would include an elected lower house, the Philippine Assembly, and the appointed Philippine Commission as the upper house. The act also extended the U.S. Bill of Rights to the Philippines.

On July 2, 1902, the secretary of war sent a telegram saying that the rebellion against the U.S. was over. Since local civil governments had been set up, the military governor's office was ended. On July 4, Theodore Roosevelt, who became U.S. president after President McKinley was assassinated, announced a full pardon for everyone in the Philippines who had taken part in the conflict. It's estimated that between 250,000 and 1 million civilians died during the war, mostly from hunger and sickness.

On April 9, 2002, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo declared that the Philippine–American War ended on April 16, 1902, when General Miguel Malvar surrendered. She made the 100th anniversary of that date a national working holiday and a special non-working holiday in Batangas province and its cities.

The Kiram–Bates Treaty secured the Sultanate of Sulu. American forces also gained control over mountainous areas that had resisted Spanish rule.

Post-1902 Hostilities

Some people believe the war unofficially continued for almost ten more years. Groups of guerrillas, religious armed groups, and other resistance fighters kept roaming the countryside. They continued to clash with American Army or Philippine Constabulary patrols until 1913. Some of this resistance came from groups claiming to be the successors to the Philippine Republic. A 1907 law made it illegal to display flags and other symbols used during the recent rebellion. Some historians consider these later fights to be part of the war.

"Insular Government" (1900–1935)

The 1902 Philippine Organic Act served as the constitution for the Insular Government. This was the U.S. civil administration in the Philippines. It was a type of territorial government that reported to the Bureau of Insular Affairs. The act said that a governor-general would be appointed by the U.S. president. It also created an elected lower house, the Philippine Assembly. The act also ended the Catholic Church's status as the state religion. The U.S. government talked with the Vatican to solve the issue of the friars (Catholic priests). The church agreed to sell the friars' lands and promised to slowly replace Spanish priests with Filipino and other non-Spanish priests. However, it refused to remove the religious orders from the islands right away. In 1904, the U.S. administration bought most of the friars' land for $7.2 million. This amounted to about 166,000 hectares, with half of it near Manila. The land was eventually resold to Filipinos, some of whom were tenants, but most were large landowners.

Under the Treaty of Paris, the U.S. agreed to respect existing property rights. They introduced a Torrens title system in 1902 to keep track of land ownership. In 1903, the Public Lands Act was passed. This law was similar to the Homestead Acts in the United States. It allowed individuals to claim land if they lived on it for five years. Both of these systems mostly helped larger landowners who could better handle the paperwork. Only one-tenth of homestead claims were ever approved.

While Philippine ports remained open to Spanish ships for ten years after the war, the U.S. began to connect the Philippine economy with its own. In terms of society and economy, the Philippines made good progress during this time. The 1909 U.S. Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act allowed free trade with the Philippines. Foreign trade was 62 million pesos in 1895, with 13% of it with the United States. By 1920, it had grown to 601 million pesos, with 66% of it with the United States. A health care system was set up. By 1930, this system reduced the death rate from all causes, including various tropical diseases, to a level similar to that of the United States. Practices like slavery, piracy, and headhunting were stopped, but not completely. Cultural developments helped strengthen a national identity, and Tagalog started to become more important than other local languages.

Two years after a census was completed, a general election was held to choose delegates for a popular assembly. An elected Philippine Assembly was formed in 1907. It served as the lower house of a two-house legislature, with the Philippine Commission as the upper house. Every year from 1907, the Philippine Assembly, and later the Philippine Legislature, passed resolutions. These resolutions expressed the Filipino people's desire for independence.

Filipino nationalists, led by Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmeña, at first strongly supported the Jones Bill of 1912. This bill suggested Philippine independence after eight years. However, they later changed their minds. They wanted a bill that focused less on a specific time and more on the conditions for independence. The nationalists demanded complete and absolute independence, guaranteed by the United States. They feared that if independence came too quickly without such guarantees, the Philippines might fall into Japanese hands. The Jones Bill was rewritten and passed by Congress in 1916, with a later date for independence.

The law, officially called the Philippine Autonomy Act but commonly known as the Jones Law, became the new constitution for the Philippines. Its introduction stated that the Philippines would eventually become independent. This would happen once a stable government was established. The law kept the governor-general of the Philippines, appointed by the U.S. president. But it created a two-house Philippine Legislature to replace the elected Philippine Assembly (lower house). It replaced the appointed Philippine Commission (upper house) with an elected senate.

Filipinos stopped their independence campaign during World War I and supported the United States against Germany. After the war, they started their independence efforts again with great energy. On March 17, 1919, the Philippine Legislature passed a "Declaration of Purposes." This statement expressed the Filipino people's strong desire to be free and sovereign. A Commission of Independence was created to find ways to achieve this goal. This commission recommended sending an independence mission to the United States. The "Declaration of Purposes" referred to the Jones Law as a true agreement between the American and Filipino peoples. It said the United States promised to recognize Philippine independence once a stable government was established. U.S. Governor-General of the Philippines Francis Burton Harrison agreed with the Philippine legislature's report about a stable government.

Independence Missions

The Philippine legislature paid for an independence mission to the U.S. in 1919. The mission left Manila on February 28. In the U.S., they met with and presented their case to U.S. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, in his farewell message to Congress in 1921, confirmed that the Filipino people had met the conditions for independence. He declared that, since this was done, the U.S. had a duty to grant the Philippines independence. However, the Republican Party controlled Congress at the time. They did not follow the recommendation of the outgoing Democratic president.

After the first independence mission, public funding for such missions was ruled illegal. Later independence missions in 1922, 1923, 1930, 1931, 1932, and two missions in 1933 were paid for by donations. Many independence bills were presented to the U.S. Congress. The Hare-Hawes-Cutting Bill passed on December 30, 1932. U.S. President Herbert Hoover vetoed the bill on January 13, 1933. Congress overrode the veto on January 17, and the Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act became U.S. law. The law promised Philippine independence after 10 years. But it kept several military and naval bases for the United States. It also put taxes and limits on Philippine exports. The law also required the Philippine Senate to approve it. Manuel L. Quezon urged the Philippine Senate to reject the bill, which they did. Quezon himself led the twelfth independence mission to Washington to get a better independence act. The result was the Tydings–McDuffie Act of 1934. This act was very similar to the Hare-Hawes-Cutting Act, with only small differences. The Tydings-McDuffie Act was approved by the Philippine Senate. The law said that the Philippines would be granted independence by 1946.

The Tydings–McDuffie Act provided for writing a constitution. It also set up a 10-year "transitional period" as the Commonwealth of the Philippines before the Philippines became fully independent. On May 5, 1934, the Philippine legislature passed a law setting the election for delegates to a convention. Governor-General Frank Murphy set July 10 as the election date. The convention held its first meeting on July 30. The finished draft constitution was approved by the convention on February 8, 1935. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved it on March 23. It was then approved by popular vote on May 14. The first election under the constitution was held on September 17. On November 15, 1935, the Commonwealth government officially began.

Philippine Commonwealth (1935–1946)

The years from 1935 to 1946 were meant for final preparations for full independence. The Philippines was given a lot of freedom during this time. However, war with Japan happened, which delayed any plans for Philippine independence.

On May 14, 1935, an election was held for the new office of president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines. Manuel L. Quezon (Nacionalista Party) won. A Filipino government was formed, based on ideas similar to the U.S. Constitution. The Commonwealth, set up in 1935, had a very strong president, a single-house national assembly, and a supreme court made up entirely of Filipinos for the first time since 1901.

Quezon's main goals were defense, social fairness, reducing inequality, diversifying the economy, and building a national identity. Tagalog was named the national language. Women were given the right to vote, and land reform was discussed. The new government began an ambitious plan to build national defense, gain more control over the economy, improve education, develop transportation, settle the island of Mindanao, and promote local businesses and industries. However, the Commonwealth also faced problems like farmer unrest, an uncertain military situation in Southeast Asia, and doubts about how much the United States would support the future Republic of the Philippines. As more farmers became restless in the late 1930s, the Commonwealth opened public lands in Mindanao and northeastern Luzon for people to settle.

In 1939–1940, the Philippine Constitution was changed. This brought back a two-house Congress. It also allowed President Quezon to be re-elected, even though he was previously limited to one six-year term.

From 1940 to 1941, Philippine officials, with American support, removed several mayors in Pampanga from office. These mayors supported land reform. After the 1946 election, some lawmakers who opposed giving the United States special economic treatment were stopped from taking office.

During the Commonwealth years, the Philippines sent one elected representative, called a resident commissioner, to the United States House of Representatives. This is similar to what Puerto Rico does today.

Japanese Occupation and World War II (1941–1945)

A few hours after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Japan launched air raids on several cities and U.S. military bases in the Philippines on December 8. On December 10, the first Japanese troops landed in Northern Luzon. Filipino pilot Captain Jesús A. Villamor, leading three P-26 "Peashooter" fighters, bravely attacked two groups of 27 enemy planes each. He shot down a much better Japanese Zero plane. For this, he received the U.S. Distinguished Service Cross. The other two planes in his flight, flown by Lieutenants César Basa and Geronimo Aclan, were shot down.

As the Japanese forces moved forward, Manila was declared an open city to prevent its destruction. Meanwhile, the government moved to Corregidor. In March 1942, General MacArthur and President Quezon left the country. Guerrilla units bothered the Japanese whenever they could. On Luzon, local resistance was so strong that the Japanese never fully controlled a large part of the island.

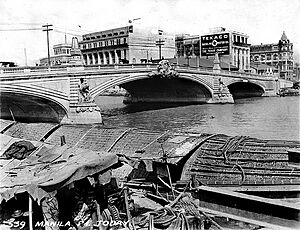

General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the United States Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), had to retreat to Bataan. Manila was taken by the Japanese on January 2, 1942. Bataan fell on April 9, 1942, and Corregidor Island, at the entrance of Manila Bay, surrendered on May 6. Terrible acts and war crimes were committed during the war, including the Bataan Death March and the Manila massacre.

The Commonwealth government then went into exile in Washington, D.C., invited by President Roosevelt. However, many politicians stayed behind and worked with the Japanese occupiers. The Philippine Commonwealth Army continued to fight the Japanese in a guerrilla war. They were considered supporting units of the U.S. Army. Several Philippine Commonwealth military awards were given to both United States and Philippine Armed Forces.

The Second Philippine Republic, led by Jose P. Laurel, was set up as a puppet state by Japan. From 1942, the Japanese occupation of the Philippines was opposed by large-scale underground guerrilla activity. The Hukbalahap, a communist guerrilla group formed by farmers in Central Luzon, did most of the fighting. The Hukbalahap, also known as Huks, fought invaders and punished those who worked with the Japanese. However, they were not very organized and were later seen as a threat to the Manila government. Before MacArthur returned, the guerrilla movement had greatly weakened Japanese control, limiting it to only 12 out of 48 provinces.

In October 1944, MacArthur had gathered enough troops and supplies to begin taking back the Philippines. He landed with Sergio Osmeña, who became president after Quezon's death. The Philippine Constabulary began active service under the Philippine Commonwealth Army on October 28, 1944, during the liberation.

The largest naval battle in history, the Battle of Leyte Gulf, happened when Allied forces started freeing the Philippines from the Japanese Empire. Battles on the islands involved long, fierce fighting. Some Japanese soldiers continued to fight even after Japan officially surrendered on September 2, 1945.

After landing, Filipino and American forces also worked to stop the Huk movement. This group was formed to fight the Japanese. The Filipino and American forces removed local Huk governments and put many high-ranking members of the Philippine Communist Party in prison. While these events happened, there was still fighting against the Japanese forces. Despite the American and Philippine actions against the Huk, the Huks still supported American and Filipino soldiers in the fight against the Japanese.

Allied troops defeated the Japanese in 1945. By the end of the war, it's estimated that over a million Filipinos died. This included regular soldiers, police, recognized guerrillas, and civilians. A 1947 report showed huge damage to most coconut and sugar mills. All inter-island shipping had been destroyed or removed. Concrete highways were broken up for military airports. Railways were not working. Manila was 80 percent destroyed, Cebu 90 percent, and Zamboanga 95 percent.

Independence (1946)

On October 11, 1945, the Philippines became one of the first members of the United Nations. On July 4, 1946, the United States officially recognized the Philippines as an independent nation. This happened through the Treaty of Manila (1946) between the U.S. and Philippine governments, during the presidency of Manuel Roxas. The treaty recognized the independence of the Republic of the Philippines. It also meant the U.S. gave up its rule over the Philippine Islands. From 1946 to 1961, Independence Day was celebrated on July 4. On May 12, 1962, President Macapagal declared Tuesday, June 12, 1962, a special public holiday. In 1964, a law changed the date of Independence Day from July 4 to June 12. It renamed the July 4 holiday as Philippine Republic Day.

World War II Veteran Benefits

During World War II, over 200,000 Filipinos fought alongside the United States against Japan. More than half of them died. As a U.S. commonwealth before and during the war, Filipinos were legally American nationals. With this status, Filipinos were promised all the benefits given to those serving in the U.S. armed forces. However, in 1946, Congress passed the Rescission Act of 1946. This law took away the benefits that Filipinos had been promised.

Since the Rescission Act was passed, many Filipino veterans have traveled to the United States. They have tried to convince Congress to give them the benefits they were promised for their service. Over 30,000 of these veterans live in the United States today, most of them U.S. citizens. Some people call these Filipino Americans "Second Class Veterans" because of their difficult situation. Starting in 1993, many bills called the Filipino Veterans Fairness Act were introduced in Congress. These bills aimed to return the benefits taken from these veterans. However, the bills never became law. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, signed into law on February 17, 2009, included money to pay benefits to the remaining 15,000 veterans.

On January 6, 2011, Jackie Speier, a U.S. Representative from California, introduced a bill. This bill aimed to make Filipino World War II veterans eligible for the same benefits as U.S. veterans. In a press conference about the bill, Speier estimated that about 50,000 Filipino veterans were still alive.

The U.S. Military in the Philippines Today

Presence of the U.S. Military

A strong presence of American soldiers is still in the Philippines today. Many people believe that a good relationship between the Philippine government and the U.S. military is the only way to improve the lives of Filipinos living in poverty. There have been at least twenty-three U.S. military bases in the Philippines since the Military Bases Agreement act was passed in 1947. Also, the U.S. has used the Philippines as a place to launch operations for wars in Asia, like the Vietnam War and the Korean War.

Visiting Forces Agreement

In 1998, the Visiting Forces Agreement allowed American forces to be in the Philippines for training exercises. It also returned former U.S. Army bases like Subic Bay, Clark, and other smaller outposts to U.S. control.

|

See also

- Negros Revolution

- Republic of Negros

- Republic of Zamboanga

- List of sovereign state leaders in the Philippines

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |