Hudson Bay expedition facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hudson Bay expedition |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

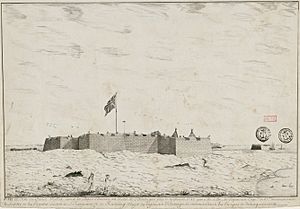

French illustration of Prince of Wales Fort in 1782 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1 ship of the line 2 frigates |

2 trading posts 3 merchantmen |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 15 drowned ~85 died of illness |

~100 captured 2 trading posts captured |

||||||

The Hudson Bay expedition was a series of attacks by the French navy on British fur trading posts. These attacks happened in 1782 on the shores of Hudson Bay in what is now Canada. A French naval group, led by Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse, carried out these raids.

The expedition started from Cap-Français in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). It was part of the American Revolutionary War, a big conflict between France and Great Britain. This war involved battles all over the world, including at sea.

Lapérouse and his ships sailed in secret. They arrived in Hudson Bay in early August 1782. Two important trading posts, Prince of Wales Fort and York Factory, belonged to the British Hudson's Bay Company. Both posts gave up without a fight. However, one British merchant ship managed to escape with some valuable furs.

Some British prisoners were sent back to England on a company ship. Others were made to join the French ships. The French crew faced many difficulties. They had not brought enough supplies for winter. Many sailors got sick with scurvy and other illnesses. The attacks hurt the Hudson's Bay Company financially. They also sadly led to the deaths of many Chipewyan fur traders who worked with the company.

Contents

Why the Expedition Happened

In late 1780, a French navy captain named Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse visited France. He suggested an idea to attack the British fur trading posts. These posts belonged to the Hudson's Bay Company. He shared his idea with Charles Pierre Claret de Fleurieu, a mapmaker and politician.

The French Secretary of State of the Navy, Charles, marquis de Castries, and King Louis XVI liked the plan. Lapérouse was given secret orders. These orders allowed him to take charge of a small fleet if the chance came up. The goal was to quickly sail north to Hudson Bay from a French-friendly port in North America.

Lapérouse did not get a chance to use his secret orders in 1781. But in April 1782, the French lost a big naval battle called the Battle of the Saintes. This defeat created a new opportunity. France and Spain had planned to attack the British colony of Jamaica. But after losing ships and their admiral, they called off the attack.

When Lapérouse arrived at Cap-Français, he suggested his plan to the new French admiral, Louis-Philippe de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil. Vaudreuil approved the idea. He gave Lapérouse three ships:

- The Sceptre (a large ship with 74 guns)

- The Astrée (a smaller, faster ship with 38 guns), led by Paul Antoine Fleuriot de Langle

- The Engageante (another smaller ship with 34 guns), led by André-Charles de La Jaille

Getting Ready for the Trip

Preparations for the expedition were done quickly and in secret. The French knew the sailing season in the far north was short. Most of the crews and officers were not told where they were going. Lapérouse even avoided bringing warm clothes to keep the mission a secret.

The fleet's official destination was listed as France, with possible stops in American ports. The captains of Astrée and Engageante received sealed orders. They were only allowed to open them when they reached the latitude of Nova Scotia.

The fleet also took on 250 soldiers from the French army. They also brought 40 artillerymen, 4 field guns, and 2 mortars. These troops were told they were going to help the French army in Newport. After two weeks of preparation, the fleet left Cap-Français on May 31, 1782.

The Expedition Begins

The French fleet reached Resolution Island without problems on July 17. This island is at the entrance to the Hudson Strait. They then sailed through the strait and into Hudson Bay.

While in the bay, the fleet saw a company ship called Sea Horse. It was sailing towards Prince of Wales Fort. Lapérouse sent one of his frigates to chase it. The captain of Sea Horse, William Cristopher, noticed the French warship seemed to lack good maps of the bay. He used a clever trick to escape.

He ordered his sails to be lowered, as if he was getting ready to drop anchor. The French captain, thinking there were shallow waters ahead, also dropped his anchor. As soon as the French ship was anchored, Cristopher quickly raised his sails and sped away. The French ship could not raise its anchor fast enough to follow.

Prince of Wales Fort Captured

On August 8, Lapérouse arrived at Prince of Wales Fort. This was a large stone fortress, but it was old and falling apart. Only 39 British traders were defending it. Its governor, Samuel Hearne, saw how large the French force was. He surrendered the fort the next day without firing a single shot. Some of his men wanted to fight, asking to use the fort's big guns.

After the surrender, the French took supplies from the fort for their ships. They also took the fort's guns. Then, they looted the fort. According to Hearne, the French took over 7,500 beaver skins, 4,000 marten furs, and 17,000 goose quills. They also spent two days trying to destroy the fort. They only managed to break the gun mounts and damage the upper walls.

Some of the British prisoners were put on a company ship called Severn. It was anchored near the fort. Other prisoners were taken aboard the French ships. Some were even made to join the French crews.

York Factory Taken

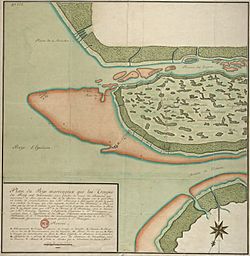

Lapérouse then gathered most of the company's small boats. On August 11, he sailed for York Factory. This was another trading post located on a piece of land between the Hayes and Nelson River. Lapérouse reported that he arrived near York Factory on August 20. The fort's defenses faced the Hayes River. The company ship King George was anchored there. The Hayes River flowed very fast, making it hard for the French to approach from that side.

Lapérouse sailed into the mouth of the Nelson River. On August 21, he moved his troops to smaller company ships. He planned an attack from the rear of the fort, about 16 miles (24 km) away. He and his engineer then checked the depth of the Nelson River. They found it was too shallow for even the smaller boats to reach solid land easily. His small boat got stuck in the mud as the tide went out. It was not freed until 3:00 AM the next morning.

Captain Langle suggested to Major Rostaing, the French troop commander, that they cross the muddy shallows on foot. They agreed, and the troops began walking through the mud. They did not know that conditions would not get much better on land. They spent the next two days walking through swamps and mud to reach the fort. Meanwhile, Lapérouse returned to the fleet because bad weather was threatening his ships. Both frigates lost their anchors when sharp rocks underwater cut their cables in the rough conditions.

York Factory was defended by 60 British traders and 12 Native Americans. When the French warships were seen, the governor of York Factory, Humphrey Marten, loaded trade goods onto the King George. He wanted to prevent them from falling into French hands. When the French arrived on August 24, Marten surrendered the fort.

Lapérouse sent a frigate after the King George when it sailed away during the night. But its captain, Jonathan Fowler, escaped. He knew the shallow waters of the bay better than the French. Rostaing took the British people from the trading post as prisoners. He destroyed any goods he could not take. He also burned York Factory to the ground. However, he made sure to leave some supplies for the Native Americans who came to trade. Lapérouse was praised by Hearne, King Louis XVI, and the British government for his kindness to the Native Americans and his British captives.

Lapérouse did not learn about the surrender until August 26. Bad weather and problems with the frigates meant he did not meet Rostaing until August 31. The surrender terms included giving up Fort Severn, another Hudson's Bay Company post. Lapérouse decided not to go to Fort Severn. It was late in the season, and his ships and men were in poor condition. Many were suffering from scurvy and other diseases. While loading goods onto the fleet, five small boats overturned, and 15 men drowned.

What Happened After

Lapérouse then began the journey back to the Atlantic Ocean. He towed the Severn as far as Cape Resolution. There, he let her go so she could sail back to England. Lapérouse sailed for Cádiz, Spain, with Sceptre and Engageante. The Astrée sailed to Brest to deliver news of the expedition's success to Paris.

The expedition was very hard on the ships' crews. By the time the ships returned to Europe, Sceptre had only 60 men healthy enough to work. This was out of nearly 500 men originally. About 70 men had died from scurvy. Engageante had 15 deaths from scurvy, and almost everyone else was sick. Both ships were also damaged by cold weather and hitting ice floes. Fleuriot de Langle was promoted to captain when he arrived in Brest in late October.

The Hudson's Bay Company said the goods taken from Prince of Wales Fort alone were worth over £14,000. Lapérouse's raid hurt the company's money so much that it did not pay any profits to its owners until 1786. When peace finally came with the 1783 Treaty of Paris, France agreed to pay the company for its losses.

The raid also permanently damaged the company's trading relationships. Chipewyan fur traders who traded with the Hudson's Bay Company suffered greatly. This was because the company could not supply them. Also, a smallpox epidemic was spreading among Native American groups. Some estimates say the Chipewyan lost half their population. The company's inability to trade for two seasons led many surviving Chipewyan to trade with European settlers in Montreal, Quebec.

Neither Hearne nor Marten was punished by the company for surrendering. Both returned to their posts the next year. When the French captured Prince of Wales Fort, they found Samuel Hearne's journal. Lapérouse claimed it as a war prize. The journal contained Hearne's stories of exploring northern North America. Hearne asked Lapérouse to return it. Lapérouse agreed, but only if Hearne published the journal. It is not clear if Hearne planned to publish it anyway. But by 1792, the year Hearne died, he had prepared a manuscript. It was published in 1795 as A Journey from Prince of Wales's Fort in Hudson's Bay to the Northern Ocean.

King Louis XVI rewarded Lapérouse with a pay raise. The expedition also made him famous in Europe and North America. His next big job was to lead a voyage of exploration into the Pacific Ocean in 1785. Fleuriot de Langle was his second in command on this trip. The fleet was last seen near Australia in spring 1788. Parts of the expedition have been found, but Lapérouse's exact fate is still unknown.

See also

- France in the American Revolutionary War

- List of Anglo-French conflicts on Hudson Bay

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |