Island of California facts for kids

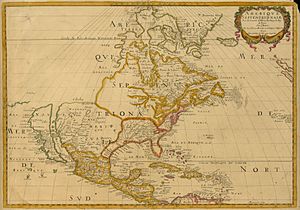

The Island of California (Spanish: Isla de California) was a big mistake on maps for a long time. Starting in the 1500s, many people believed that California was a huge island. They thought it was separated from mainland North America by a body of water. This water is now known as the Gulf of California.

This idea was one of the most famous map errors in history. It appeared on many maps during the 1600s and 1700s. This happened even though explorers found proof that it was wrong. At first, people even thought California might be a paradise, like the Garden of Eden or Atlantis. This map mistake wasn't just a one-time thing. From the mid-1500s to the late 1700s, there was a lot of debate about California's geography. For example, a Spanish map from 1548 showed California as a peninsula. But a Dutch map from 1622 showed it as an island. There are over 1,000 maps showing California as an island in one collection alone.

Contents

How the Island Idea Started

The first time the "Island of California" was mentioned was in a book. It was a romance novel from 1510 called Las sergas de Esplandián. The author, Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo, described an island like this:

"Know, that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons."

This book was very popular when Europeans first explored California. Many people think it inspired the name "California." It also likely made early explorers think the Baja California Peninsula was the island from the story.

Early Explorations and Discoveries

In 1533, a sailor named Fortún Ximénez discovered the southern part of Baja California. This was near where La Paz is today. He was killed by local people, but his crew returned to New Spain (Mexico). They told others about their discovery. In 1535, Hernán Cortés arrived in the same bay. He named the area Santa Cruz. Cortés tried to start a colony there but gave up after a few years. His limited information about southern Baja California likely led to the area being named after the legendary California. It also led to the early, but short-lived, belief that it was a large island.

In 1539, Cortés sent the navigator Francisco de Ulloa to explore further north. Ulloa sailed along the Gulf and Pacific coasts of Baja California. He reached the mouth of the Colorado River at the top of the Gulf. This seemed to prove that the region was a peninsula, not an island. Ulloa described the land as "High and bare, of wretched aspect without any verdure." Another trip, led by Hernando de Alarcón, went up the lower Colorado River. This trip confirmed Ulloa's findings. Maps made in Europe after this, like those by Gerardus Mercator and Abraham Ortelius, correctly showed Baja California as a peninsula.

How the Island Myth Spread

Instead of many mapmakers making the same mistake, it's thought that maps showing California as an island spread because they were copied. Mapmakers in the early 1600s often copied other maps. What's interesting is that the first maps showing California as an island appeared after a series of correct maps. Friar Antonio De La Ascension, a high-ranking Spanish priest, was the first known person to draw California as an island in 1603.

On his way back to Acapulco, Mexico, Friar Antonio's ship was captured by Dutch pirates. They found and took a map he had drawn. This map showed California as an island. This meant secret information was leaked. Spain usually kept information about its explorations private. For example, maps from Sebastián Vizcaíno's expedition, which Friar Antonio was on, weren't published until 1802. That was 200 years later! Soon after Friar Antonio's map was taken, Dutch maps started showing California as an island. A British map from 1630 by Henry Briggs even had a note saying, "California, sometimes supposed to be a part of the western continent, but since by a Spanish chart taken from Hollanders, it is found to be a goodly island." This stolen map was Friar Antonio's. This note shows how the idea of California as an island spread. Since the Dutch were respected mapmakers, the idea grew. Most maps showing California as an island were published after 1622. Throughout the 1600s, Dutch, Japanese, French, Germans, and British mapmakers all drew California as an island.

The Northwest Passage Idea

Another reason for the confusion might have been the second trip of Juan de Fuca in 1592. De Fuca claimed he explored the western coast of North America. He said he found a large opening that might connect to the Atlantic Ocean. This was the legendary Northwest Passage. Finding a Northwest Passage was a big goal for many explorers in California. It would be very profitable for Europe to find a northern trade route to Asia. Explorers like Sebastián Vizcaíno were even told to sail north until they found this passage. They were only to turn back if the coast went northwest, which would mean no waterway and that the land was connected to Asia.

De Fuca's claim is still debated because there's only one written account of it. It's his story told to an Englishman, Michael Locke. Still, this account says de Fuca found a large strait with a big island at its mouth. This was around 47° north latitude. The Strait of Juan de Fuca is actually around 48° N. The southern tip of Vancouver Island is also there. The Gulf of California ends much farther south, around 31° N. It's possible that explorers and mapmakers in the 1600s mixed up these two places. More exploration was definitely needed. Even the famous British explorer James Cook just missed the Strait of Juan de Fuca in March 1778. He even named Cape Flattery (in modern Washington state), which is at the mouth of the strait. Cook stopped in Nootka Sound off Vancouver Island. His account says he "saw nothing like [the Strait of Juan de Fuca]; nor is there the least probability that ever any such thing existed." However, Cook mentioned bad weather around that time. He did go on to map most of the outer Pacific coastline of North America on that same trip.

Proving California Was a Peninsula

A key step in changing ideas about California came from a land trip. This trip was led by Juan de Oñate, the first governor of Santa Fe de Nuevo México. His group went down the Colorado River in 1604 and 1605. They thought they saw the Gulf of California continuing to the northwest. This would have been behind the Sierra de Los Cucapah mountains into the Laguna Salada Basin and Lake Cahuilla.

Reports from Oñate's trip reached Antonio de la Ascención. He was a Carmelite friar who had been on Sebastián Vizcaíno's explorations of California's west coast in 1602 and 1603. Ascención strongly supported Spanish settlement in California. His later writings still called the region an island. Spanish leaders and local people knew where the Gulf of California actually ended. But by extending the coastline north past Cape Mendocino and even into Puget Sound, they could challenge Francis Drake's claim of Nova Albion for England (1579). They wanted to show that Cortés's claim (1533) came first.

The Jesuit missionary and mapmaker Eusebio Francisco Kino brought back the truth: Baja California was a peninsula. While studying in Europe, Kino had believed California was an island. But when he arrived in Mexico, he started to have doubts. He made several land trips from northern Sonora to areas near the Colorado River Delta between 1698 and 1706. He did this partly to find a good route between Jesuit missions in Sonora and Baja California. But he also wanted to solve the geography question. Kino became convinced that a land connection had to exist. Other Jesuits in the 1700s generally followed his lead. The first report of Kino's discovery and his map from 1701, showing California as a peninsula, were sent to Europe. This was done by Marcus Antonius Kappus, another Jesuit missionary. In a letter from June 1701, he wrote about it to his friend Philippus Alberth in Vienna. This helped spread the correct information. However, Juan Mateo Manje, a military friend on some of Kino's trips, was still unsure. European mapmakers remained divided on the question.

Jesuit missionary-explorers in Baja California tried to finally settle the issue. These included Juan de Ugarte (1721), Ferdinand Konščak (1746), and Wenceslaus Linck (1766). The matter was finally settled without any doubt when the trips of Juan Bautista de Anza traveled between Sonora and the west coast of California from 1774 to 1776.

See also

In Spanish: Isla de California para niños

In Spanish: Isla de California para niños