Lake Cahuilla facts for kids

Lake Cahuilla was a huge lake that existed a long time ago in California and northern Mexico. It's also known as Lake LeConte or Blake Sea. This ancient lake covered a large area, including the Coachella and Imperial Valleys. During the Holocene period (the last 11,700 years), it was about 12 meters (39 feet) above sea level. Even earlier, during the Pleistocene Ice Age, it was much higher, reaching up to 31–52 meters (102–171 feet) above sea level.

Most of the water for Lake Cahuilla came from the Colorado River. The lake would overflow near Cerro Prieto, sending water into the Rio Hardy, which then flowed into the Gulf of California.

The lake formed many times when the Colorado River changed its path. This happened because the Salton Trough, a deep valley, was separated from the ocean by the growing Colorado River Delta. Large earthquakes along faults like the San Andreas Fault might have caused the river to change course. The weight of the lake's water might have even triggered some earthquakes! Over time, Lake Cahuilla left behind old shorelines and beach deposits like gravel bars and travertine rock.

Lake Cahuilla appeared and disappeared several times over the last 2,000 years. It would fill up, then dry out, and finally vanished sometime after 1580. Later, between 1905 and 1907, an accident caused the Salton Sea to form in some parts of the old lake bed. If people hadn't stepped in, the Salton Sea might have grown as big as Lake Cahuilla once was. Today, the fertile lands of the Imperial and Coachella Valleys are where the lake used to be.

The Algodones Dunes were created from sand left by Lake Cahuilla. This sand was then blown by the wind. The lake was full of life, including fish, clams, and plants along its shores. These natural resources helped ancient people live there. We know this from many old sites and stories from the Cahuilla people. The lake may have even affected how people moved around and how languages developed in the area.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name "Lake Cahuilla" was first used in 1907 by William Phipps Blake. The United States Geological Survey officially recognizes it. The lake is named after the Cahuilla people, who have many traditional stories about it. They called the lake paul. Their myths say that when their creator was cremated, tears made the lake salty.

Another name, "Blake Sea," also honors William Phipps Blake. The name "Lake LeConte" was created in 1902 by Gilbert E. Bailey. It's sometimes used for the lake that existed during the Ice Age. This name comes from Joseph LeConte, a geography professor.

Today, "Lake Cahuilla" is also the name of a reservoir in the Coachella Valley. It's also the name of a place where scientists study earthquakes in California.

Where Was Lake Cahuilla?

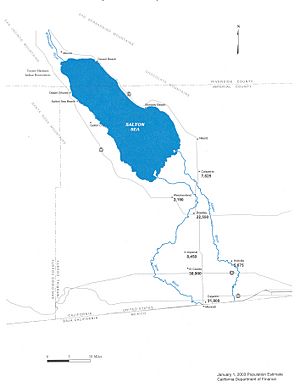

Lake Cahuilla was located in the area of the modern-day Salton Sea. It stretched from the southern part of the Coachella Valley in the north, through the Imperial Valley in the south, and down to the Cerro Prieto area in Baja California, Mexico. This whole area is also called the Colorado Desert. Today, about 5,400 square kilometers (2,100 square miles) of this land is below sea level.

Many towns today are in areas that were once covered by Lake Cahuilla. These include Indio, Thermal, Mecca, Niland, Calipatria, Brawley, Imperial, and El Centro. Even Calexico and Mexicali might have been underwater. Today, the New River and Alamo River flow through the old lakebed. The Whitewater River and San Felipe Creek flow into the area from other directions.

The main shorelines of the lake were about 12 meters (39 feet) above sea level. The southern shore was south of the US-Mexico border. Lake Cahuilla was about 160 kilometers (100 miles) long and 56 kilometers (35 miles) wide. It reached a depth of about 91 meters (300 feet) when the water was 12 meters (39 feet) above sea level. The lake's largest size was around 5,700 square kilometers (2,200 square miles). At its fullest, Lake Cahuilla held about 480 cubic kilometers (115 cubic miles) of water. This made it much larger than the Salton Sea today and one of the biggest lakes in Holocene North America.

Places like Bat Caves Butte and Obsidian Butte were islands in the lake when it was full. The eastern shores were fairly straight, facing hills and mountains like the Indio Hills and Chocolate Mountains. The western shore was more uneven, facing the Santa Rosa Mountains.

How Lake Cahuilla Got Its Water

Lake Cahuilla was mainly filled by water from the Colorado River. Other water sources, like groundwater or rain, didn't add much. To keep Lake Cahuilla at 12 meters (39 feet) above sea level, it needed about half of the Colorado River's water. This meant that when the lake was filling, almost no river water reached the Gulf of California.

The Colorado River's sediment built up in its delta, which sometimes pushed water into the Lake Cahuilla area. Rivers in a delta often change their paths. Big floods might have caused the river to switch course. Once the river flowed into the Lake Cahuilla basin, it tended to stay there because the slope was steeper than towards the Gulf of California. The river would have flowed into the lake through the Alamo River and the New River. It might have taken 12–20 years for the lake to fill up to 12 meters (39 feet) above sea level.

When the Colorado River flowed into Lake Cahuilla, all its sediment (about 150 million tons per year) went into the lake. This caused the lake to fill with sediment. When the lake's inlet filled with sediment, the Colorado River would change its course back to the Gulf of California, and the lake would start to dry up.

Other smaller streams also flowed into Lake Cahuilla, like the Whitewater River from the north and San Felipe Creek from the southwest. These streams are usually dry today. During the Ice Age, these local streams might have carried more water, possibly even supporting Lake Cahuilla on their own.

Lake Shorelines

The old shorelines of Lake Cahuilla can be seen at different heights, usually between 25–60 feet (7.6–18 meters) above sea level. The most recent high water level lasted long enough to create clear shorelines. Fish fossils found near the coast suggest that lagoons (shallow bodies of water) connected to the lake. As the lake level changed, it left behind layers of sand and gravel called beach berms. If the lake had dried up only by evaporation, it would have taken about 70 years for 96 meters (315 feet) of water to disappear.

A good place to see the shoreline is at Travertine Point in the Santa Rosa Mountains. You can see a clear line where the dark rock above the shoreline meets the lighter rock below it.

The shoreline looks different in various places. On the east, there are 25-foot (7.6-meter) high cliffs carved by waves. Farther south, there are long sandbars, one reaching 5.6 kilometers (3.5 miles) long. Even farther south, you can find beaches made of small, flat stones, showing how strong the waves were. The lake also left behind deposits of gravel and sandbars. White, crusty deposits called tufas formed along the shorelines, especially on the northwestern side.

Water Quality

Scientists can tell from the shells of freshwater molluscs (like snails and clams) that Lake Cahuilla was a freshwater lake when it was full. However, when the water level was lower, fossils show that the water became saltier. It might have been a bit salty (brackish) at times. The water might have been fresher where the Colorado River entered and saltier farther north.

Water Movement

High cliffs and piles of pebbles show that there were strong waves on the northeastern shore. These waves were caused by strong northwesterly winds. On the other hand, the gentle slopes on the southern side of the lake probably meant less wave action there.

Strong northwesterly winds likely created currents that moved south along the eastern shores. These currents helped form beaches from sediment carried into the lake from the north.

How Water Left the Lake

Only about half of the Colorado River's water was needed to keep Lake Cahuilla full. The rest flowed into the Gulf of California. Lake Cahuilla likely overflowed at a spot near Cerro Prieto, which was about 12 meters (39 feet) above sea level. This overflow flowed into the Gulf of California through the Rio Hardy. Studies of the water in the lake suggest that it was mostly a closed lake, meaning not much water flowed out. Some water might have also soaked into the ground to fill underground water storage.

The current overflow point to the Gulf of California is about 9 meters (30 feet) above sea level. It was probably higher in the past, allowing Lake Cahuilla to reach higher levels. Over time, the river changed, and the lake levels dropped. Lava flows from the Cerro Prieto volcano might have helped keep the overflow point stable against erosion.

Once the Colorado River stopped flowing into Lake Cahuilla, the lake would have evaporated quickly, at a rate of about 1.8 meters (6 feet) per year. It would have completely dried up in about 53 years. Even as the lake was shrinking, the Colorado River might have still reached it sometimes.

Weather Around the Lake

Today, the Lake Cahuilla area is very dry and hot in the summer. Temperatures can range from 10–35°C (50–95°F), sometimes reaching 51°C (124°F). It only rains about 64 millimeters (2.5 inches) per year. The mountains to the west get much more rain. Water evaporates very quickly here, up to 1,800 millimeters (71 inches) per year.

Winds over the lake were likely strong. Northwesterly winds could reach speeds of 50 kilometers per hour (31 mph), and westerly winds were often around 24 kilometers per hour (15 mph). These winds created big waves and currents along the eastern shores of the lake.

It's harder to know the exact weather during the Ice Age, but it was probably not much wetter than today, except in the mountains. The changes in the Colorado River's path were likely the main reason Lake Cahuilla formed. Other large lakes also formed in the Mojave desert during that time.

A colder climate brought cold-loving animals to lower areas. Glaciers even formed on the San Bernardino Mountains. It was probably windier back then. Studies of the lake's deposits show that a wet period ended about 9,000 years ago. Long droughts happened between 6,200 and 2,000–3,000 years ago.

Earth's Movements and Volcanoes

Lake Cahuilla formed where the Gulf of California's tectonic zone meets the San Andreas Fault system. This causes volcanic activity and earthquakes. The San Andreas Fault runs near the northeastern edge of Lake Cahuilla. Earthquakes have left marks in the lake's sediments.

The Cahuilla Basin, also called the Salton Sink, is part of a larger valley that extends into the Gulf of California. This basin is filled with many kilometers of sediment, showing how quickly the land has sunk over time. About four million years ago, the Colorado River started flowing into this area. The growth of the Colorado River Delta then separated the Salton Trough from the Gulf of California during the Ice Age.

Faults and Earthquakes

When Lake Cahuilla existed, individual earthquakes could cause the ground to shift by as much as 1 meter (3.3 feet). Sediments from Lake Cahuilla show signs of ground movement caused by earthquakes, similar to what happened in the 1971 San Fernando earthquake. Scientists have found evidence of at least eight earthquakes in the lake's sediments, dating from around 900 AD to the 1700s.

Some scientists think that the weight of the water in Lake Cahuilla might have triggered earthquakes along the San Andreas Fault and other faults. This is called "induced seismicity" and is known to happen near large reservoirs. On the other hand, earthquakes could have caused the Colorado River to change its course, leading to the lake filling or drying up. For example, the 1892 Laguna Salada earthquake caused big ground shifts that could have led to flooding.

The San Andreas Fault has moved ancient Indian stone rings. Its path is now covered by sediments from Lake Cahuilla. Other faults that crossed the lake's shores include the Extra fault zone, the Coyote Creek Fault, the Superstition Mountain Fault, and the San Jacinto Fault. These faults have all shown movement over time.

Faults on the lake floor itself include the Brawley Seismic Zone, the Imperial Fault, and the Kane Springs Faults. The Imperial Fault may have moved at the same time as the San Andreas Fault when Lake Cahuilla was full.

Volcanoes

Several volcanoes were located on the floor of Lake Cahuilla. Today, they can be seen at the southeastern edge of the Salton Sea. These include Cerro Prieto and the Salton Buttes. Cerro Prieto has two lava domes that are about 200 meters (660 feet) high. There are also mud pots and mud volcanoes in the Cahuilla Basin. Geothermal energy (heat from the Earth) is used in some parts of this region.

The Salton Buttes are five lava domes that stretch for about 7 kilometers (4.3 miles). They are made of rhyolite rock. These domes are named Mullet Hill, Obsidian Butte, Red Island, and Rock Hill. Obsidian Butte was originally above water, but Lake Cahuilla covered it when the lake was full. Red Island erupted while it was underwater, creating volcanic ash deposits.

Scientists have used different dating methods to figure out the age of these volcanoes. Some of the Salton Buttes are thousands of years old, but some still release steam today. Cerro Prieto is also very old, but stories from the native Cocopah people might suggest it was active more recently.

Obsidian from Obsidian Butte has been found in places as far as 500 kilometers (310 miles) away. People started using this obsidian between 510 BC and 640 AD. This suggests that Obsidian Butte could only be used as a source once Lake Cahuilla no longer covered it. When the lake was full, Obsidian Butte was underwater, but at lower water levels, it would have been an island.

Life in and Around the Lake

Bivalves, like clams, lived along the shores of Lake Cahuilla. Their shells are sometimes found in tunnels they made. People living there probably ate them or used them to make beads. Many types of snails were also found, like Amnicola longinqua and Physella ampullacea. Tiny crustaceans called Ostracods were present too. Even Sponges have been found as fossils. One mammal found in the lake was the muskrat.

The lake created an oasis in the desert. Plants like arrowweed, tule (a type of reed), and willowweed grew along the shores. Mesquite trees grew farther away from the water. Other plants found in the lake's sediments include evening primrose, pine trees, and sunflowers.

Bird species around Lake Cahuilla were similar to those around the Salton Sea today. They included different kinds of grebes, American coots, American white pelicans, and various types of ducks.

Many fish species lived in Lake Cahuilla, including Cyprinodon macularius, Mugil cephalus, and Ptychocheilus lucius. The fish species in Lake Cahuilla were similar to those found in the lower Colorado River.

Tiny algae called Diatoms were also present in the lake. When the lake level rose, plants in the flooded areas died, and their remains were washed ashore. The lake supported five fish species and many waterfowl. The plants and animals along the shores were likely strong enough to handle drops in the lake level for a while before the water became too salty.

The Lake's Story Over Time

When Did Lake Cahuilla Exist?

Lake Cahuilla's history goes back to the late Pleistocene and Holocene periods. The lake was at its largest about 40,000 years ago. During the Pleistocene, shorelines were higher, around 31–52 meters (102–171 feet) above sea level. Evidence at Travertine Point shows a lake existed there 13,000 years ago. Holocene lake levels were generally lower, not going above 12 meters (39 feet) above sea level.

The most recent time Lake Cahuilla was full was about 400–550 years ago. Water levels of 12 meters (39 feet) above sea level happened between 200 BC and 1580 AD. The well-preserved shorelines and lack of soil suggest that the lake was at its biggest in recent times.

At first, people thought the lake existed in one long period. However, later studies showed that it went through many wet and dry phases. Each phase lasted a long time. Most scientists now believe there were five or six separate times the lake was full. For example, some theories suggest high water levels around 100 BC – 600 AD, 900–1250 AD, and 1300–1500 AD. At least 12 different cycles of the lake growing and shrinking happened over the last 2,000–3,000 years. The basin probably wasn't completely dry between the last few times it was full.

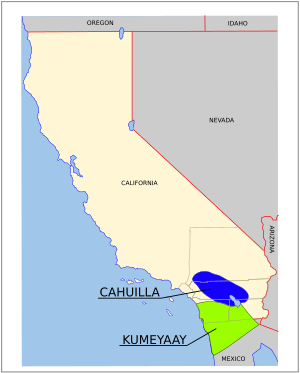

Some legends from the Kumeyaay and Cahuilla tribes talk about Lake Cahuilla. They say the lake bed was often dry but would sometimes flood, forcing the tribes to move to the mountains. It's not clear if the lake was still full when Spanish explorers arrived in the region, but it probably was.

It's uncertain if the lake was full before or after 1540, when the Coronado expedition passed through the area. Some reports from that expedition suggest the lake was not full. However, later explorers like Juan de Oñate in 1605 and Eusebio Kino in 1702 reported that native people told them about a lake. A map from around 1762 also shows the Colorado River flowing into a lake. Based on observations from Juan Bautista de Anza in 1774, Lake Cahuilla did not exist then. But a short refilling might have happened between 1680–1825.

Sometimes, old dates from Lake Cahuilla deposits might be wrong because the Colorado River carried old carbon into the lake.

Small, temporary lakes likely formed in the Lake Cahuilla basin during Colorado River floods, such as in 1828, 1840, and 1862. In 1873, Joseph Widney suggested recreating the entire sea to increase rain for farming. This was called the "Widney Sea." Since 1905–1907, a new lake, the Salton Sea, has existed where Lake Cahuilla once was. This happened when heavy spring runoff from the Colorado River broke an irrigation canal. The Salton Sea might have grown as big as Lake Cahuilla if people hadn't worked to stop the flood.

What Lake Cahuilla Left Behind

The Algodones Dunes, which are next to the old Cahuilla shorelines, were formed by sand blown from Lake Cahuilla. This idea was first suggested in 1923. The sand was likely carried to the dune field when the lake dried up and its bed was exposed to the wind.

Fine clay and silt were deposited in the lake. Closer to the shore, sand was also left behind. The material left by Lake Cahuilla is known as the Cahuilla formation. These lake sediments cover the northern part of the Colorado River Delta and give the ground a grayish color. The clays left by the lake were used by ancient people to make ceramics. Also, Lake Cahuilla is responsible for the very fertile soils of the Coachella Valley and Imperial Valley, which are important farming areas in the United States. Halite (salt) deposits left by the lake were mined in the 1800s and 1900s.

The huge weight of the water in Lake Cahuilla caused the ground beneath it to sink by about 0.4 meters (1.3 feet). This sinking of the ground has also been seen at other ancient lakes and modern reservoirs.

A type of land snail, Cahuillus, is named after the lake.

Ancient Life Around the Lake

Many ancient sites of the Cahuilla people have been found on the lake's shores. These include campsites, places where fish remains and shell piles were found, and fishing weirs (structures to trap fish). This shows that early people in the area lived closely with Lake Cahuilla. When the lake dried up, it likely changed their lives. Ancient pottery and stone tools have been found along the Lake Cahuilla shoreline, as well as petroglyphs (rock carvings) in the travertine rock.

Fish traps are often seen along the old shorelines. About 650 fish weirs were found. These were probably built every year. This "fishing industry" likely stopped as the water went down, because there were fewer fish in the shrinking lake.

Studies show that the lake supported a large population of people who relied mostly on the lake's resources, including fishing. Estimates suggest between 20,000 and 100,000 people lived there. When the lake dried up, these people switched to other ways of getting food. Farming was not a main food source for them.

The Elmore Site, discovered in 1990, is near the southwestern coast of Lake Cahuilla. It was active after the lake waters had left the area, probably for a short time around 1660–1680 AD. Bones (mostly from birds), pottery, charcoal from fires, storage pits, and shells were found there.

The repeated filling and drying of Lake Cahuilla likely had a big impact on the communities around it. The lake's large size meant that many different groups of people were affected. Evidence shows that at least three different groups—Cahuilla, Kumeyaay, and Cocopah—lived around the lake in its later history. The lake's growth was probably good for these communities, unlike for the Colorado River Delta, which lost some of its water. The way languages are spread in the region might show the effects of Lake Cahuilla's changes. People moving because the lake dried up or flooded may have led to new connections between different language groups.

When Lake Cahuilla filled, it might have encouraged Quechan people to move to the area. This move might have helped spread farming to the Peninsular Ranges. When Lake Cahuilla dried out after 1500 AD, these people likely moved back south and west. This movement might be recorded in the traditional stories of the Quechan people. Legends also tell of lost ships, sometimes described as pirate ships, that sailed Lake Cahuilla and are now buried in the Colorado Desert.

See also

In Spanish: Lago Cahuilla para niños

In Spanish: Lago Cahuilla para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |