Johann Jakob Froberger facts for kids

Johann Jakob Froberger (baptized 19 May 1616 – 7 May 1667) was a German Baroque composer, a very skilled keyboard player, and an organist. He was one of the most famous composers of his time. He helped create the musical form called the suite of dances in his keyboard pieces. His music for the harpsichord often told a story or described something, which is called programmatic music.

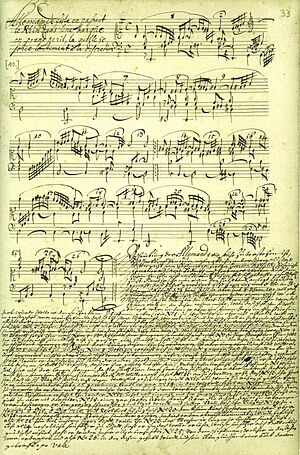

Only two of Froberger's many musical works were printed while he was alive. Froberger didn't want his handwritten music to be published. He only allowed his rich supporters and friends, especially the Württemberg and Habsburg families, to have access to his music. After he died, his music went to his patroness, Sibylla, Duchess of Württemberg, and the Württemberg family's music library.

Contents

Life of a Musician

Early Years in Stuttgart (1616–1634)

Johann Jakob Froberger was baptized on 19 May 1616 in Stuttgart, Germany. We don't know his exact birth date. His family came from Halle. His father, Basilius (1575–1637), was a singer (a tenor) in the Württemberg court chapel starting in 1599.

Basilius married Anna Schmid (1577–1637) before 1605. By the time Johann Jakob was born, his father was very successful. In 1621, Basilius became the court Kapellmeister, which means he was in charge of the court's music. Four of his eleven children became musicians, so Johann Jakob likely learned music from his father first.

Stuttgart had a rich musical life, with musicians from all over Europe. This meant Froberger heard many different kinds of music from a young age. We don't know much about his early schooling. He might have learned from Johann Ulrich Steigleder. He also might have met Samuel Scheidt when Scheidt visited Stuttgart in 1627. It's possible Froberger sang in the court chapel, but there's no clear proof. Court records show that an English lutenist (lute player) named Andrew Borell taught lute to one of Basilius Froberger's sons in 1621–22. If this was Johann Jakob, it would explain his later interest in French lute music.

His father's music library also helped Froberger's education. It had over a hundred music books, including works by famous composers like Josquin des Prez, Samuel Scheidt, and Michael Praetorius.

Working in Vienna and Traveling to Italy (1634–1649)

The court music group in Stuttgart, called the Hofkapelle Stuttgart, was stopped in 1634. This happened after the Protestants lost the Battle of Nördlingen during the Thirty Years' War.

A writer named Mattheson said that a Swedish ambassador was so impressed by Froberger's music that he took the 18-year-old to Vienna. The ambassador supposedly helped him get a job at the imperial court. However, this seems unlikely because Sweden was against the imperial forces at that time. So, how Froberger ended up in Vienna around 1634 and became a singer in the imperial chapel is still a mystery.

In 1637, Froberger's father, mother, and one sister died from the plague. Johann Jakob and his brother Isaac sold their father's music library to the Württemberg court. This is how we know what was in his father's library. In the same year, Johann Jakob became a court organist in Vienna, helping Wolfgang Ebner.

In June 1637, he got permission and money to go to Rome to study with Frescobaldi, a famous composer. Froberger stayed in Italy for three years. Like many musicians who studied there, he seemed to have become Catholic. He returned to Vienna in 1641 and worked as an organist and chamber musician until late 1645. Then, he took a second trip to Italy.

It was once thought that Froberger studied with Giacomo Carissimi, but new research suggests he most likely studied with Athanasius Kircher in Rome. If so, Froberger probably wanted to learn how to write vocal music. Frescobaldi, who taught him instrumental music, had died in 1643. Around 1648–49, Froberger might have met Johann Kaspar Kerll and possibly taught him.

In 1649, Froberger traveled back to Austria. On his way, he stopped in Florence and Mantua. He showed off the arca musurgica, a special music machine Kircher had taught him about, to some Italian princes. In September, he arrived in Vienna and showed the arca musurgica to Emperor Ferdinand III, who loved music. He also gave the Emperor Libro Secondo, a collection of his own compositions. (His Libro Primo is now lost.) Also in September, Froberger played for William Swann, an English diplomat. Through Swann, he met Constantijn Huygens, who became Froberger's lifelong friend. Huygens introduced Froberger to music by French composers like Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, Denis Gaultier, and Ennemond Gaultier.

Years of Travel (1649–1653)

After Empress Maria Leopoldine died in August 1649, the court's musical activities stopped. Froberger left Vienna and traveled widely for the next four years. He was likely given secret diplomatic tasks by the Emperor, similar to what artists like John Dowland and Peter Paul Rubens did during their travels. We don't know much about these trips.

He probably visited Dresden first. He played for John George I, the Elector of Saxony, and gave him a collection of his works. In Dresden, he also met Matthias Weckmann, and they became lifelong friends. They wrote letters to each other, and Froberger even sent some of his music to Weckmann to show his style.

According to one of his students, after Dresden, Froberger visited Cologne, Düsseldorf, Zeeland, Brabant, and Antwerp. We also know he visited Brussels at least twice (in 1650 and 1652) and London. His trip to London was difficult; he was robbed, an event he described in his musical piece Plainte faite à Londres pour passer la mélancholie. Most importantly, he visited Paris at least once in 1652.

In Paris, Froberger likely met many important French composers, including Chambonnières, Louis Couperin, Denis Gaultier, and possibly François Dufault. The last two were famous lute players who wrote in a special French style called style brisé. This style influenced Froberger's later harpsichord suites. In turn, Louis Couperin was greatly influenced by Froberger's music. One of Couperin's pieces even has the subtitle "à l'imitation de Mr. Froberger" (meaning "in the style of Mr. Froberger").

In November 1652, Froberger saw his friend, the famous lutenist Blancrocher, die. Blancrocher reportedly died in Froberger's arms. Although Blancrocher wasn't a major composer, his death was important in music history. Couperin, Gaultier, Dufaut, and Froberger all wrote tombeaux (musical laments) about his death.

Last Years and Death (1653–1667)

In 1653, Froberger traveled through Heidelberg, Nuremberg, and Regensburg before returning to Vienna in April. He stayed with the Viennese court for the next four years. During this time, he created at least one more music collection, the Libro Quarto of 1656. (His Libro Terzo is now lost.)

Froberger was very sad when Emperor Ferdinand III died on 2 April 1657. He wrote a lament (a sad musical piece) in memory of the Emperor. His relationship with the new Emperor, Leopold I, was difficult for political reasons. Froberger's mentor and friend Kircher was important in the Jesuit order, and Froberger had strong connections with the court of the Elector-Archbishop of Mainz. Both were against Leopold's election. However, Froberger did dedicate a new book of his works to Leopold. On June 30, 1657, Froberger received his last payment as a member of the imperial chapel.

We know little about Froberger's last 10 years. Most information comes from letters between Constantijn Huygens and Duchess Sybilla of Montbéliard (1620–1707). After her husband died in 1662, the Duchess lived in Héricourt. Froberger became her music teacher around the same time. This shows he kept a connection with the Württemberg family from his Stuttgart days. He lived in Château d’Héricourt, the Duchess's home.

The letters between Huygens and Sybilla show that in 1665, Froberger traveled to Mainz. He performed at the court of the Elector-Archbishop of Mainz and met Huygens in person for the first time. In 1666, Froberger planned to return to the imperial court in Vienna. However, he never did. He lived in Héricourt until his death on 6 or 7 May 1667. Froberger seemed to know he was going to die soon, as he made all necessary arrangements the day before he passed away.

Froberger's Musical Works

How His Music Was Kept

Only two of Froberger's pieces were published during his lifetime. One was the Hexachord Fantasia, published by Kircher in 1650. The other was a piece in François Roberday's Fugues et caprices (1660).

However, many of his works were saved in handwritten copies. The three main collections of Froberger's music are:

- Libro Secundo (1649) and Libro Quarto (1656): These are two beautifully decorated books dedicated to Emperor Ferdinand III. They were found in Vienna. Johann Friedrich Sautter, Froberger's friend, did the decorations and handwriting. Each book has four sections and 24 pieces. Both include six toccatas and six suites. Libro Secundo also has 6 fantasias and 6 canzonas, while Libro Quarto has 6 ricercars and 6 capriccios instead.

- Libro di capricci e ricercate (around 1658): This book contains 6 capriccios and 6 ricercars.

In 2006, a handwritten music book by Froberger himself was found. It reportedly had 35 pieces, 18 of which were new and had never been published. This book is from Froberger's last years and might contain his final compositions. Many other handwritten copies of Froberger's music exist. Sometimes, his pieces appear in several different versions, either because he kept changing them or because the people copying them weren't careful.

Two main numbering systems are used to identify Froberger's works:

- DTÖ numbers (or Adler numbers): These were used in early 20th-century publications. They number pieces by type, like Toccata No. 4 or Suite No. 20.

- FbWV numbers: These are from the Siegbert Rampe catalogue, created in the early 1990s. This catalogue is more complete and includes newly found pieces. For example, Adler Toccata No. 1 is FbWV 101.

Harpsichord Suites and Story-Telling Pieces

Froberger is often seen as the creator of the Baroque suite. While other composers tried to organize dance pieces, Froberger's suites were much more artistic. A typical Froberger suite usually had four movements: allemande, courante, sarabande, and gigue. However, the gigue's place in the suite changed over time. In his earliest works, the gigue was sometimes missing or placed as the second movement. Later, it became the last movement, which was the standard after he died.

Froberger's dances often had two repeated sections, but they weren't always the same length. This made his music sound less predictable. He also used a French lute style called style brisé in many of his pieces, especially after his visit to Paris. This style involves short, broken chords and figures.

His allemandes (a type of dance) often didn't follow the original dance rhythm. Instead, they had many short musical ideas, ornaments, and fast runs. His courantes were usually in 6/4 time, with a lively feel. His sarabandes were mostly slow and in 3/2 time. The gigues were almost always fugal, meaning they had melodies that were repeated and layered by different voices, like a chase.

Some of Froberger's works have written instructions like "f" (loud) and "piano" (soft) for echo effects, "doucement" (gently), and "avec discrétion" (with expressive freedom). These instructions helped players understand how to perform the music.

Besides suites, Froberger also wrote descriptive pieces for the harpsichord that had titles. He was one of the first composers to write such "programmatic" pieces, which told a story or described an event. These pieces were often very personal. Their style was similar to his allemandes, with irregular rhythms and style brisé features.

Here are some examples of his story-telling pieces:

- Allemande, faite en passant le Rhin dans une barque en grand péril (Allemande, made while crossing the Rhine in a boat in great danger)

- Lamentation faite sur la mort très douloureuse de Sa Majesté Impériale, Ferdinand le troisième, An. 1657 (Lamentation on the very painful death of His Imperial Majesty, Ferdinand the Third, Year 1657)

- Plainte faite à Londres pour passer la melancholie (Lament made in London to pass the melancholy)

- Tombeau fait à Paris sur la mort de Monsieur Blancrocher (Tombeau made in Paris on the death of Mr. Blancrocher)

These works often used musical ideas to represent things. For example, in the laments for Blancrocher and Ferdinand IV, Froberger used a descending scale to show Blancrocher's fatal fall down stairs and an ascending scale for Ferdinand's rise to heaven. He often explained these pieces in writing, sometimes in great detail. For instance, the Allemande, faite en passat le Rhin has 26 numbered sections with explanations for each. The Blancrocher tombeau has a written introduction explaining how the lutenist died.

Keyboard Music with Many Voices

The rest of Froberger's keyboard works can be played on any keyboard instrument, including the organ. His toccatas are the only ones that have some free, improvisational parts. Most of his other pieces are strictly polyphonic, meaning they have several independent melodic lines playing at the same time.

Froberger's toccatas are similar to those by Michelangelo Rossi, who also studied with Frescobaldi. Instead of many short parts, they have a few well-connected sections that switch between strict polyphony and free, improvisational passages. They are usually of medium length.

Froberger's fantasias and ricercares are quite similar to each other. A typical Froberger ricercare or fantasia uses one main musical idea throughout the piece, with different rhythms in different sections. The music follows the strict rules of 16th-century counterpoint.

Froberger's canzonas and capriccios are also similar in style. He built these pieces like sets of variations in several sections. The main musical ideas in these pieces are always faster and livelier than those in his ricercares and fantasias.

Other Musical Works

The only surviving works by Froberger that are not for keyboard are two motets (choral pieces): Alleluia! Absorpta es mors and Apparuerunt apostolis. These are found in the Düben collection, put together by Gustaf Düben, a famous Swedish collector. The music is kept in the Uppsala University library. These motets are similar in style. Both are for a three-voice choir (soprano, tenor, bass), two violins, and organ. They are written in the early 17th-century Venetian stile concertante, which means they feature contrasting groups of instruments or voices.

Froberger's Lasting Impact

Even though only two of Froberger's works were published during his lifetime, his music was widely shared across Europe through handwritten copies. He was one of the most famous composers of his time. Because he traveled a lot and could combine different national musical styles into his own music, Froberger helped spread musical ideas throughout Europe. He was also one of the first major keyboard composers in history. He was the first to focus equally on both the harpsichord/clavichord and the organ.

Many composers knew and studied Froberger's music, including Johann Pachelbel, Dieterich Buxtehude, Georg Muffat and his son Gottlieb Muffat, Johann Kaspar Kerll, Matthias Weckmann, Louis Couperin, Johann Kirnberger, Johann Nikolaus Forkel, Georg Böhm, George Handel, and Johann Sebastian Bach. Even Mozart copied Froberger's Hexachord Fantasia, and Beethoven knew Froberger's work through his teacher. Froberger had a deep influence on Louis Couperin, helping to change French organ music and develop the unmeasured prelude.

While his polyphonic pieces were highly valued in the 17th and 18th centuries, today Froberger is mostly remembered for his role in developing the keyboard suite. He almost single-handedly created this form. By treating standard dance forms in new and creative ways, he prepared the way for Johann Sebastian Bach's amazing contributions to the genre.

Notable Recordings

- Johann Jakob Froberger: The Complete Keyboard Works (1994). Richard Egarr (organ, harpsichord). Globe GLO 6022–6025

- This recording is organized by manuscript and keeps the original order of the pieces. It does not include works discovered after 1994. It also has some pieces by other composers that were once thought to be by Froberger.

- The Unknown Works (2003/4). Siegbert Rampe (organ, harpsichord, clavichord). MDG 341 1186-2 and 341 1195-2

- This recording features about 20 newly discovered works (mostly suites) and pieces whose composer is uncertain.

- The Strasbourg Manuscript (2000). Ludger Rémy (harpsichord). CPO 9997502

- This includes fourteen suites from the recently found Strasbourg Manuscript. Only three of these were known from Froberger's own handwritten copies before.

- Froberger Edition (2000–). Bob van Asperen (harpsichord, organ). AE 10024, 10054, 10064, 10074 (harpsichord), AE 10501, AE 10601, AE 10701 (organ)

- This series is planned to have 8 parts. Volume 4 uses the newest discoveries from the Berliner Singakademie manuscripts.

- Johann Jakob Froberger: Complete Music for Harpsichord and Organ (2016). Simone Stella (organ, harpsichord). 16 cd box Brilliant Classics BC 94740

- As of 2016, this is the most up-to-date complete recording. It is organized by where the music was found and includes newly discovered works.

Media

See also

In Spanish: Johann Jakob Froberger para niños

In Spanish: Johann Jakob Froberger para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |