John Perkins (Royal Navy officer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Perkins

|

|

|---|---|

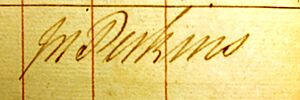

Signature of Captain John Perkins from the Logbook of HMS Arab 1800, held at The National Archives, Kew, London

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Jack Punch |

| Born | Kingston, Jamaica |

| Died | 27 January 1812 Kingston, Jamaica |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1775–1804 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Commands held | HM Schooner Punch HMS Endeavour HMS Spitfire HMS Marie Antoinette HMS Drake HMS Meleager HMS Arab HMS Tartar |

| Battles/wars | American Revolution Fourth Anglo-Dutch War French Revolutionary Wars Napoleonic War |

John Perkins (died 27 January 1812), known as Jack Punch, was a brave officer in the British Royal Navy. He was likely the first mixed-race officer to hold a high position in the Royal Navy. Perkins started from humble beginnings and became a very successful ship's captain during the Georgian period.

During the American War of Independence, he commanded a small 10-gun schooner. In just two years, he captured over 300 enemy ships! Later in his career, Perkins worked as a spy for the navy. He went on secret missions to Cuba and Saint-Domingue (which is now Haiti).

At the start of the rebellion in Saint-Domingue, he was caught. He was even sentenced to death for helping the rebels with weapons. After being rescued, he was promoted to commander in 1797. Then, in 1800, he became a post-captain. Perkins even caused a small international problem with Denmark when he fired on two of their ships during peacetime. Near the end of his time in the navy, he helped capture the islands of Saint Eustatia and Saba from the French. He also bravely attacked a large 74-gun warship with his smaller 32-gun frigate.

Contents

John Perkins was probably born in Kingston, Jamaica, in the mid-1700s. We don't know much about his early life. One story, written many years after he died, said he was of mixed race. In the West Indies at that time, mixed-race people often faced many challenges. However, some mixed-race sons of important white men were given an education. This might have been the case for Perkins.

In 1775, Perkins first appeared in Royal Navy records. He joined the 50-gun HMS Antelope. This ship was the main ship for the commander of the Jamaica naval base. Perkins was an extra pilot because he knew the West Indies ports very well. People said his knowledge of the different ports was unmatched.

Commanding the Punch

In 1778, Perkins was given command of the schooner Punch. This ship likely had ten small guns. It was around this time that he got his famous nickname, "Jack Punch." He probably earned it because of the name of his ship. Over the next two years, Perkins claimed to have captured 315 enemy ships. This means he captured about three ships every week! The Jamaican House of Assembly later confirmed his amazing success.

Admiral Sir Peter Parker and other admirals used Perkins for secret missions. He went on missions against the French in Cap-Français and the Spanish in Havana, Cuba. Admiral Parker eventually made Perkins a lieutenant. He then gave him command of Endeavour. The 12-gun Endeavour was an American-built schooner.

Governor Archibald Campbell wrote a letter praising Perkins. He said that Perkins's brave actions led to hundreds of enemy ships being captured or destroyed. He also said that over three thousand enemy men became prisoners of war for Britain. The governor added that Captain Perkins was admired by his officers and respected by the enemy.

Challenges and Demotion

In 1782, Perkins captured a much larger ship with important French officers on board. The commander of the Jamaica station, Admiral George Rodney, promoted Perkins. He made him master and commander of Endeavour. Rodney also added two more guns to the ship, making it a 14-gun sloop-of-war.

However, Admiral Rodney's promotion of Perkins was not allowed by higher authorities. Rodney wrote to Philip Stephens, the First Secretary to the Admiralty. He tried to get the promotion approved. Rodney explained that Perkins was already a lieutenant and commander of the Endeavour schooner when he arrived in Jamaica. He also said Perkins had an excellent reputation and had done great service. Despite Rodney's request, Perkins was demoted back to lieutenant. The extra guns were also ordered to be removed from his ship. When the American War of Independence ended, Perkins was "on the beach." This meant he did not have a ship to command and was on half-pay.

For several years, from 1783 to 1790, Perkins was not listed in the Royal Navy's records. Some French and English records suggest he might have been involved in piracy during this time. In 1790, Perkins asked the Jamaican House of Assembly for help. He wanted their support to get promoted. After reviewing his achievements, the assembly agreed to ask the Admiralty to promote him to post-captain.

Captured in Saint-Domingue

In 1790, Perkins volunteered for service again. He served under Admiral Philip Affleck. For a few years, there is no official record of him commanding a ship. But in 1792, Captain Thomas McNamara Russell of the 32-gun frigate HMS Diana was on a mission to Saint-Domingue. He learned that a British officer was arrested and about to be executed in Jérémie. The officer was accused of giving weapons to the rebels fighting for their freedom.

Britain and France were not officially at war at this time. So, Captain Russell asked for Perkins to be released. The French authorities promised to release him but then refused. After many letters were exchanged, Russell realized the French would not let Perkins go. Russell sailed his ship to Jérémie and met with the 12-gun HMS Ferret. They agreed that an officer named Godby would go ashore to get Perkins. The two ships would stay offshore, ready to help if needed. Lieutenant Godby landed, and after talks, Perkins was finally released. After this, Perkins disappears from the records for a short time again.

Back in Service

In September 1793, Perkins returned to the Navy's official list. He was listed as commanding HMS Spitfire, a small 4-gun schooner. He joined Commodore John Ford's squadron. This squadron was part of a British campaign in Saint-Domingue, requested by French Royalists. When they arrived, Ford's squadron captured many ships. One was a French Navy schooner called Convention Nationale. It was renamed HMS Marie Antoinette, and Ford gave command of it to Perkins. Ford described Perkins as "an Officer of Zeal, Vigilance and Activity."

In 1794, Marie Antoinette was part of Rear Admiral Ford's squadron. This squadron, with Brigadier General John Whyte, briefly captured Port-au-Prince. About forty-five ships were in the harbor, and all were captured. In 1796, Marie Antoinette was part of a small group of ships that captured the schooner Charlotte and the brig Sally. Perkins stayed with Marie Antoinette until he was promoted to master and commander.

Becoming a Commander

We don't know the exact details of his promotion. But in 1797, Admiral Hyde Parker promoted Perkins to commander of HMS Drake. This was a brig with 14 guns. Later, HMS Drake, along with other ships under Captain Hugh Pigot, attacked enemy ships at Port-de-Paix. They captured eight enemy ships on April 20, 1797. On October 25, 1798, Drake captured the French privateer La Favorite. Perkins received 53 pounds, 13 shillings and 9 pence as his share of the prize money.

While commanding Drake, Perkins and Solebay (Captain Poyntz) captured four French corvettes. These were the 18-gun Egyptienne, the 16-gun Eole, the 12-gun Levrier, and the 8-gun Vengeur. This happened on November 24, 1799, off Cape Tiburon.

Promotion to Post-Captain

Perkins was promoted on September 6, 1800. He became a post-captain in the 32-gun frigate HMS Meleager. In early 1801, Perkins moved to the 22-gun HMS Arab.

The Battle of West Key

In March 1801, Arab, along with the 18-gun British privateer Experiment, found two Danish ships. These were the brig Lougen, commanded by Captain Carl Wilhelm Jessen, and the schooner Den Aarvaagne. According to Danish accounts, Arab approached the Danish ships and fired without warning. Lougen was hit but not badly damaged, and it began to fire back steadily.

Experiment first tried to capture Aarvaagne. But Aarvaagne followed orders to stay out of the fight. It escaped south to Christiansted on St Croix. Experiment then joined Arab in attacking Lougen. The two British ships surrounded the Danish ship. During the fight, which lasted over an hour, a shot from Lougen hit Arab and caused its anchor to fall. Perkins reported that this was the first shot from Lougen. Arab's crew could not cut the anchor free. This meant Arab could not move well. This allowed Captain Jessen to steer Lougen to safety. He got under the protection of shore batteries and then into St Thomas. The Danish government honored Captain Jessen for his actions. He received a gold sword, a medal, and 400 rixdollars.

On April 13, 1801, Arab captured the Spanish privateer Duenda.

Capturing Saint Eustatia and Saba Islands

On April 16, 1801, Perkins, with Colonel Richard Blunt and some soldiers, attacked and captured the rich islands of Sint Eustatius and Saba. They captured the French soldiers there, forty-seven cannon, and 338 barrels of gunpowder. Eustatia had been the most profitable island in the Dutch West Indies. After more voyages, Perkins was moved to the 32-gun frigate HMS Tartar in 1802.

Later Career

Between November 20 and December 4, 1803, Tartar was with Commodore John Loring's squadron. The squadron captured several French warships. These included Le Decouverte, La Clorinde, La Surveillante, La Vertu, and Le Cerf. La Surveillante and La Clorinde were later used by the British Navy. General Rochambeau, the commander of French forces on Saint-Domingue, was on La Surveillante when it surrendered.

On July 25, 1804, Tartar was with HMS Vanguard (Captain James Walker). They were involved in capturing the French 74-gun ship of the line Duquesne. Two 16-gun brigs were sailing with Duquesne. Tartar was faster than the larger British ships. It kept Duquesne and its companions busy until the bigger British ships arrived. Then, the French squadron surrendered. A sailor's share of the prize money from this capture was 6 shillings and 8 pence. A petty officer's share was 1 pound, 13 shillings and 11 pence.

Final Mission to Haiti

In January 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the leader of the rebellion in Haiti, declared Haiti's independence from France. Admiral Duckworth and Governor Nugent sent Perkins in Tartar to Haiti. He went as a British observer to see what was happening on the island. Edward Corbet, a government advisor, went with Perkins.

Perkins described the situation in Haiti in his official letters. He wrote about the terrible sights in the streets. He saw bloodstains and bodies left by the river and sea. He even wrote that when they were fishing, several bodies got caught in their net. He said that such cruel and destructive scenes were impossible to imagine or describe.

Retirement and Death

In March 1804, Perkins left the navy because of health problems. It is said that Perkins finally visited England in 1805, but there is no proof. There are no more records of him being involved with the Navy or Haiti. John Perkins died on January 27, 1812, at his home in Jamaica. His obituary said he had suffered from a condition called "asthma" for many years, and this caused his death. His obituary in the Naval Chronicle praised his actions while commanding the schooner Punch. It said he bothered the enemy more than any other officer with his brave actions and the huge number of prizes he took.

The will of John Perkins, "a captain in His Majesty's Royal Navy," was approved in 1819. The Jamaica Almanac for 1812 shows that Perkins owned the Mount Dorothy estate in Saint Andrew Parish, Jamaica. He also owned 26 people who were enslaved. He likely used some of his prize money to buy property in Jamaica. In his will, Perkins said that all his property should be sold after his death. After paying for his funeral and debts, the money was to be used to support two women, Roberta Walker and Judith Lassley. It was also to provide for seven boys and four girls whom he recognized as his children.

See also

- Slavery in the British and French Caribbean

Images for kids