Josef von Sternberg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Josef von Sternberg

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Jonas Sternberg

May 29, 1894 Vienna, Austria-Hungary (present-day Austria)

|

| Died | December 22, 1969 (aged 75) Los Angeles, California, U.S.

|

| Years active | 1925–1957 |

| Spouse(s) |

Riza Royce

(m. 1926; div. 1930)Jean Annette McBride

(m. 1945; div. 1947)Meri Otis Wilner

(m. 1948) |

| Children | Nicholas Josef von Sternberg |

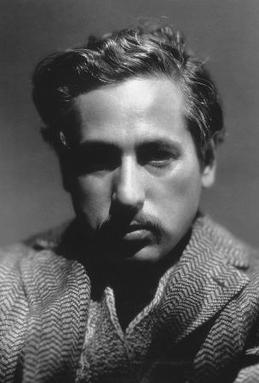

Josef von Sternberg (born Jonas Sternberg; May 29, 1894 – December 22, 1969) was a famous Austrian-American filmmaker. He made movies during a big change in film history, from silent movies to movies with sound. He worked with many of the biggest film studios in Hollywood.

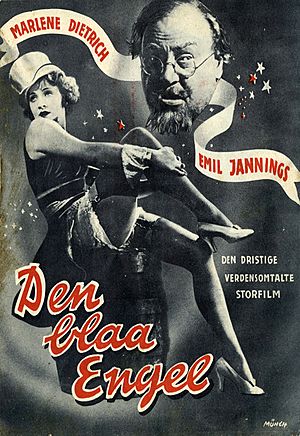

He is most famous for working with the actress Marlene Dietrich in the 1930s. Together, they made popular films like The Blue Angel (1930). Sternberg's films are known for their amazing pictures, detailed sets, and special lighting that made scenes feel very emotional. He also helped start the "gangster film" style with his silent movie Underworld (1927). His movies often showed people trying hard to stay true to themselves, even when they made big sacrifices for love.

He was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director for his films Morocco (1930) and Shanghai Express (1932).

The Life of Josef von Sternberg

Early Years and Moving to America

Josef von Sternberg was born Jonas Sternberg in Vienna, Austria-Hungary. His family was not rich. When he was three, his father moved to the United States to find work. His mother and five children, including Jonas, joined his father in America in 1901. Jonas was seven years old then.

He later said that when they arrived in the new world, immigration officers checked them "like a herd of cattle." Jonas went to public school for three years. Then, his family, except his father, moved back to Vienna. Even later in life, Sternberg remembered Vienna fondly.

His father wanted him to study the Hebrew language very strictly. Jonas's parents did not have a happy relationship. His father was very strict at home. These early challenges helped shape the unique stories he told in his films.

Starting a Career in Film

In 1908, when Jonas was 14, he moved back to New York with his mother. He became an American citizen that year. After a year, he stopped going to Jamaica High School. He worked many different jobs, like making hats and selling things door-to-door. He also worked in a lace factory. There, he learned about the fancy fabrics he would later use to decorate his movie sets and dress his actresses.

In 1911, at age 17, "Josef" Sternberg started working at the World Film Company. He cleaned and fixed film reels. At night, he worked as a movie projectionist. By 1914, he became a chief assistant. He wrote titles for silent films and edited movies. This was when he first got official credit for his film work.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, he joined the US Army. He worked in the Signal Corps in Washington, D.C. There, he took pictures for training films for new soldiers. After the war, Sternberg worked for different film studios in America and Europe. He was a film cutter, editor, writer, and assistant director.

How "von" Was Added to His Name

The "von" in Sternberg's name sounds like it means he came from a noble family. But it was actually added by a film producer named Elliott Dexter. In 1923, when Sternberg was an assistant director, Dexter thought adding "von" would make his name sound more artistic and important for the film.

Another director, Erich von Stroheim, who was also from Vienna and was someone Sternberg admired, had also added a fake "von" to his name. Sternberg later said that people criticized him for the "von" in the 1930s. They thought it made him seem too fancy and not focused on real-life problems.

Learning to Direct: 1919–1923

Sternberg spent years learning from early silent filmmakers. In 1919, he worked as an assistant director on The Mystery of the Yellow Room. He learned a lot from director Emile Chautard about photography and how to arrange things in a film shot. This helped Sternberg become known as a master of "pictorial composition" in movies.

During this time, other famous films were being made, like D. W. Griffith's Broken Blossoms and Charlie Chaplin's Sunnyside. Sternberg traveled in Europe between 1922 and 1924, making movies in London. When he returned to California in 1924, he worked as an assistant director on Vanity's Price. People noticed his skill, especially in a hospital scene.

Directing His First Films

The Salvation Hunters: 1924

At 30 years old, Sternberg directed his first movie, The Salvation Hunters. He made it independently with actor George K. Arthur on a very small budget of $4,800. This film impressed famous director Charlie Chaplin and producer Douglas Fairbanks Sr. The movie showed three young people trying to survive in a difficult world.

Even with its small budget, United Artists bought the film for $20,000. It was shown for a short time but did not make much money. However, because of this film, actress Mary Pickford hired Sternberg to write and direct her next movie. But his script was too experimental, and their project was canceled.

The Salvation Hunters was a very personal film for Sternberg. It showed his unique style, using veils and nets to create interesting visuals. It focused on how characters felt inside, rather than just on action.

Working at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer: 1925

After leaving United Artists, Sternberg was seen as a rising talent in Hollywood. He signed a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (M-G-M) in 1925 to make eight films. However, Sternberg believed movies were art, while M-G-M cared more about making money. These different ideas caused problems. Sternberg was not very interested in making films just to be successful at the box office.

M-G-M first asked him to direct The Exquisite Sinner. This romance movie was set after World War I. It was never released because the story was hard to follow, even though it looked beautiful.

Next, Sternberg was asked to direct The Masked Bride. He was frustrated because he had no control over the movie. He quit after two weeks, even turning the camera to the ceiling as he left. M-G-M ended his contract in August 1925.

Working with Chaplin Again: 1926

After his difficult time at M-G-M, Sternberg returned from Europe. Charlie Chaplin then asked him to direct a movie for his former lead actress, Edna Purviance. She had been in many of Chaplin's films but had not had a main role in a while. This was the only time Chaplin let another director make one of his productions.

Chaplin liked how Sternberg showed his characters in The Salvation Hunters. He wanted Sternberg to do more of that. The film was first called The Sea Gull but was changed to A Woman of the Sea.

Chaplin was disappointed with the film Sternberg made. It was very visual and artistic, but it did not have the human warmth Chaplin expected. Even though Sternberg re-shot some scenes, Chaplin decided not to release the movie, and the film copies were later destroyed.

Success at Paramount Pictures: 1927–1935

The problems with Chaplin's film hurt Sternberg's career for a short time. In 1926, he went to Berlin to consider managing stage shows, but it was not for him. He then went to England and married Riza Royce, an actress who had helped him on A Woman of the Sea. Their marriage was difficult and they divorced in 1928, remarried, and then divorced again in 1931.

Silent Films: 1927–1929

In 1927, Paramount producer B. P. Schulberg hired Sternberg to help with lighting and photography. Sternberg helped fix a movie called Children of Divorce that the studio thought was worthless. He worked for three days straight, re-shot half the movie, and turned it into a success.

Impressed, Paramount asked Sternberg to direct a big movie about Chicago gangsters called Underworld. This film is often called the first "gangster" movie. It showed a criminal as a tragic hero. Sternberg created a fantasy gangster world that came from his own imagination. Underworld was a huge success and won an Academy Award. This showed Paramount that Sternberg could make popular films.

Over the next two years, Sternberg made four more films for Paramount: The Last Command (1928), The Drag Net (1928), The Docks of New York (1929), and The Case of Lena Smith (1929). This was a very busy time for him. While critics liked The Last Command, none of these films made much money for Paramount.

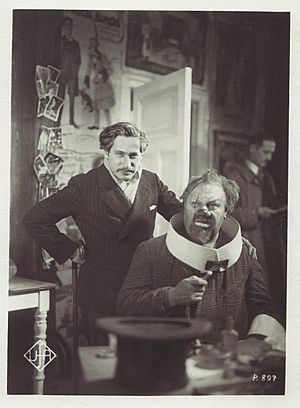

The Last Command also helped Sternberg work with actor Emil Jannings and producer Erich Pommer. Sternberg also helped edit another director's film, which unfortunately ended his friendship with that director.

The Drag Net is now a lost film. The Docks of New York is still popular today. It mixes exciting visuals with deep character feelings in a story about love in a tough city.

Out of the nine silent films Sternberg made, only four still exist today. This makes it hard to fully understand all his work from that time. However, he is still seen as a great "Romantic artist" of the silent film era.

The Case of Lena Smith, his last silent movie, is unfortunately lost. It was seen as his best attempt at combining a meaningful story with his unique style. But it was ignored in America because "talkies" (movies with sound) were becoming popular. In Europe, it was highly regarded.

Sound Films and Marlene Dietrich: 1929–1935

Paramount quickly added sound to Sternberg's next film, Thunderbolt (1929). This movie used new sound effects for humor. The main actor, George Bancroft, was nominated for an Academy Award. But Sternberg's future at Paramount was still uncertain because his previous films had not made much money.

The Blue Angel: A Big Success (1930)

In 1929, Sternberg was asked to go to Berlin to direct Emil Jannings in his first sound film, The Blue Angel. This became the most important film of Sternberg's career. Sternberg cast the then unknown Marlene Dietrich as Lola Lola. Dietrich became a huge international star overnight. She then followed Sternberg to Hollywood to make six more films with him.

Film historian Andrew Sarris said The Blue Angel is Sternberg's most powerful work. He said it is a film that even the director's biggest critics agree is excellent.

Sternberg's strong feelings for his new star caused problems on set. Jannings, the older actor, was upset that Sternberg paid so much attention to Dietrich. It was like the movie's story, where Dietrich's character rises while Jannings's character falls.

Working with Marlene Dietrich in Hollywood: 1930–1935

Sternberg and Dietrich made six amazing and talked-about films for Paramount. These included Morocco (1930), Dishonored (1931), Shanghai Express (1932), Blonde Venus (1932), The Scarlet Empress (1934), and The Devil is a Woman (1935).

These stories were often set in exciting places like the Sahara Desert, China, or Imperial Russia. Sternberg's unique artistic style was clear in these films. He used rich sets and special techniques. He was not very concerned about publicity or how much money his movies made. He had a lot of control over these films, which allowed him to create them exactly as he wanted with Dietrich.

Morocco (1930) and Dishonored (1931)

Paramount wanted to build on the success of The Blue Angel. So, they started making Morocco in Hollywood, starring Gary Cooper, Dietrich, and Adolphe Menjou. Morocco was very successful at the box office. Both Sternberg and Dietrich got contracts for three more films and higher salaries. The film was nominated for four Academy Awards.

Dishonored, Sternberg's second Hollywood film with Dietrich, was finished before Morocco was released. It was an espionage thriller with a lighthearted feel. The movie ends with Dietrich's character, Agent X-27, being executed by the military.

An American Tragedy: 1931

Dishonored did not make as much money as the studio hoped. While Dietrich was in Europe, Paramount asked Sternberg to direct a film based on the novel An American Tragedy.

The famous Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein was supposed to direct it first, but his ideas were rejected. Sternberg took over. He kept the main story but changed the themes. The author of the novel, Theodore Dreiser, was very angry and sued Paramount, but he lost.

The film uses many images of water to show the main character's motivations and fate. The photography was very good. However, Sternberg was a replacement director, so he did not feel as connected to the project. The film is quite different from his other works from that time. Sternberg did not care much about the mixed reviews it received.

When Dietrich returned to Hollywood in 1931, Sternberg was a top director at Paramount. He was ready to make some of his greatest films. The first of these was Shanghai Express.

Shanghai Express: 1932

The main idea of Shanghai Express is about secrets and desires. It shows a romantic struggle between Dietrich's character and Clive Brook's character. Sternberg slowly reveals the true natures of the people on the train. Dietrich's character, Shanghai Lily, is mysterious.

Sternberg showed complete control over every part of this film: the sets, the photography, the sound, and the acting. The cinematographer, Lee Garmes, won an Academy Award. Sternberg and the movie were also nominated for awards.

Blonde Venus: 1932

When Sternberg started his next film, Blonde Venus, Paramount Pictures was having financial problems. They needed successful films. The studio wanted Dietrich to play a more traditional American housewife, instead of the daring characters she had played before.

Sternberg's original story for Blonde Venus was about a woman who falls on hard times but is eventually forgiven by her husband. The studio did not like the ending at first. When Sternberg refused to change it, Paramount threatened to sue him. Dietrich supported Sternberg. They made small changes that satisfied the studio.

Blonde Venus begins with Dietrich marrying a chemist. She becomes a housewife with a young son. But when her husband needs expensive medical treatment, she becomes a nightclub performer and mistress to a gangster. The story becomes very wild as Dietrich travels the world with her son, restarting her stage career.

The movie is supposedly about a mother's love for her child. But Sternberg used it to show his own childhood difficulties. Blonde Venus is known for its beautiful visuals and detailed sets. The movie is sometimes criticized for its uneven story and supporting cast.

One famous scene is the "Hot Voodoo" nightclub sequence, where Dietrich comes out of an ape costume. Paramount's hopes for Blonde Venus were too high given the tough economic times. While it did make some money, it was not a huge success. This made the studio less willing to support more Sternberg-Dietrich films.

Sternberg and Dietrich thought about starting their own film company in Germany. But their plans were ruined when the Nazis came to power in 1933. Both Sternberg and Dietrich reluctantly signed new contracts with Paramount.

Feeling frustrated with Paramount, Sternberg decided to make one of his most grand films, The Scarlet Empress. This film would challenge Paramount and mark a new phase in his work.

The Scarlet Empress: 1934

The Scarlet Empress is a historical drama about the rise of Catherine the Great. Sternberg created a fantastical 18th-century Imperial Russia for this film. The movie follows young Sophia as she grows up to become the Empress of Russia. The incredibly rich sets and decorations are meant to show how the director and star were controlled by the powerful studio.

The film was not popular with critics or the public. Americans were dealing with financial problems and were not interested in a movie that seemed overly fancy. This failure hurt Sternberg's reputation.

Sternberg knew that The Devil is a Woman would be his last film with Paramount. His relationship with Dietrich was also getting worse. With the studio's permission, Sternberg had full control over this final film with Marlene Dietrich.

The Devil is a Woman: 1935

The Devil is a Woman was Sternberg's film tribute to Marlene Dietrich. It showed his thoughts on their five years of working and personal connection.

The story is set during a carnival in Spain in the late 1800s. A love triangle forms between a young revolutionary, an older military officer, and the beautiful Concha (played by Dietrich). Even though the setting is joyful, the film has a dark and thoughtful mood. The story ends with a duel where the officer is wounded.

In this film, Sternberg chose an actor who looked a lot like him. This showed that the film was also about his own career struggles and losing Dietrich as a close partner. The conversations in the film are full of bitter feelings. Sternberg used many layers of decorations in front of the camera to create a deep, three-dimensional look. This control over visuals made his films very powerful.

In March 1935, Paramount announced that Sternberg's contract would not be renewed. Sternberg himself said that he and Dietrich had gone "as far as possible" together and continuing would be "harmful to both of us."

Even with good reviews, The Devil is a Woman hurt Sternberg's standing in the film industry. He would never again have the same level of support or fame he had at Paramount. The Spanish government even protested the film, saying it insulted Spanish people. Paramount agreed to stop showing the film to protect trade agreements.

Working at Columbia Pictures: 1935–1936

After Paramount faced bankruptcy, many talented people left. Producer Schulberg and screenwriter Furthman went to Columbia Pictures. They helped Sternberg get a contract there to make two films.

Crime and Punishment: 1935

Sternberg's first project at Columbia was an adaptation of the Russian novel Crime and Punishment. This was not a good match for his skills. Many studios were making films based on classic books at the time because the copyrights had expired, so they did not have to pay fees.

Sternberg added some style to the film, but he did not capture the deep character analysis of the book. Instead, it became a simple detective story. Even so, Sternberg showed he was a capable director, and Columbia was satisfied.

The King Steps Out: 1936

Columbia had high hopes for Sternberg's next film, The King Steps Out, a musical comedy starring opera singer Grace Moore. The film was about Austrian royalty in Vienna. However, there were many disagreements between the opera star and the director. Sternberg found it hard to connect with the lead actress or adapt his style to a musical. He quickly left Columbia Pictures after finishing the film. The King Steps Out is the only movie he ever wanted removed from any list of his works.

After his difficult time at Columbia, Sternberg built a unique home in the San Fernando Valley. It had a fake moat, an eight-foot steel wall, and bulletproof windows. This fortress-like home showed his worries about his career and his desire to control his own life.

From 1935 to 1936, Sternberg traveled a lot in Asia. He met Japanese film distributor Nagamasa Kawakita, with whom he would later work on his final film in 1953. In Java, Sternberg got a serious infection and had to return to Europe for surgery.

Unfinished Project: I, Claudius: 1937

While recovering in London, Sternberg was asked by London Films to direct a film about the Roman Emperor Claudius. Marlene Dietrich had helped convince them to choose Sternberg.

The story of Claudius, played by Charles Laughton, was perfect for Sternberg. Claudius was an older, smart man who unexpectedly became emperor. He tried to rule fairly but became corrupted by power. This idea of good being ruined by power was very appealing to Sternberg.

The studio wanted to start filming quickly because Charles Laughton's contract was ending. Sternberg brought a lot of discipline to the set. However, he soon clashed with Laughton, who was a famous actor. Sternberg liked to make his actors "mere details of décor," which Laughton did not like.

Laughton needed a lot of help from the director to get into his role. Sternberg and Laughton had many "artistic arguments." After five weeks, Laughton said he would leave when his contract ended. Sternberg was frustrated, saying he was making art, not racing a deadline.

On March 16, actress Merle Oberon was seriously injured in a car accident. The studio used this as an excuse to stop the film, which was already having problems with disagreements and rising costs. The film was never finished.

This was a big blow for Sternberg. The parts of the film that still exist suggest it could have been a truly great work. When the production stopped, Sternberg lost his last chance to be a top filmmaker again. He was reportedly very upset after the film was canceled. He stayed in Europe from 1937 to 1938, trying to find work. He tried to make other films, but they all fell through due to various reasons, including his health and Germany invading Austria. He returned to California with a chronic heart condition.

Return to M-G-M: 1938–1939

In 1938, M-G-M asked Sternberg to finish some scenes for another director's film, The Great Waltz. After that, the studio hired him for one movie to direct Hedy Lamarr. M-G-M hoped he could make Lamarr as popular as he had made Marlene Dietrich.

Sternberg worked on New York Cinderella for just over a week before he quit. The movie was finished by another director and was not well-received.

Sternberg then returned to crime dramas, a genre he helped create, to fulfill his contract with M-G-M. He directed Sergeant Madden.

Sergeant Madden: 1939

This film is about a police patrolman who becomes a sergeant. He has a family with his own son and adopted children. His biological son turns to crime and dies in a shootout. His adopted son becomes a good cop and marries his deceased brother's wife.

The film's themes and style are similar to German films made after World War I. It shows that duty to society is more important than family loyalty. The story of the adopted son proving his worth to society by replacing the biological son is a common idea in German stories. The conflict between the son and the powerful father in Sergeant Madden also reminds some of Sternberg's own childhood struggles with his strict father.

Sternberg's film techniques in Sergeant Madden use dark, shadowy lighting, similar to German Expressionist films of the 1920s. Even though the main actor, Wallace Beery, was known for being loud, Sternberg got a more controlled performance from him.

Last Classic Film: The Shanghai Gesture: 1941

Sternberg's work on Sergeant Madden impressed Hollywood executives. United Artists gave him the chance to make his last classic film, The Shanghai Gesture.

The Shanghai Gesture: 1941

The original play for The Shanghai Gesture was very scandalous. It was difficult to adapt in 1940 because of strict film rules. Screenwriters changed the story to make it acceptable. Sternberg added his own touches and agreed to direct it.

The story is set in a Shanghai casino. The owner is called "Mother Gin-Sling." Her daughter, Gene Tierney, is from a European school but is still seen as degraded.

War Work and Later Life

The Town: 1943

During World War II, Sternberg made a short documentary called The Town for the United States Office of War Information. This 11-minute film showed a small American town in the Midwest. It focused on the cultural contributions of its European immigrants.

This documentary was different from Sternberg's usual artistic style. It was a very realistic film, but it still showed his excellent sense of composition. The Town was translated into 32 languages and shown overseas in 1945.

After the war, Sternberg worked as an advisor on the film Duel in the Sun. He also tried to find support for a personal project about his childhood, but he could not get funding. He then returned to his home in Weehawken, New Jersey.

Jet Pilot: 1951

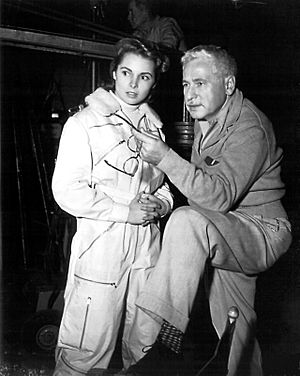

After two years without work, Sternberg married Meri Otis Wilmer in 1948 and had a child. In 1949, he was hired by Howard Hughes' RKO studios to direct a color film. He had to do a film test, even though he was 55 years old. He passed and got a two-picture contract. In 1950, he began filming the Cold War-era movie Jet Pilot.

Sternberg agreed to make a traditional movie about aviation. The story was like a comic book. A Soviet pilot-spy, Janet Leigh, lands her plane in Alaska. An American pilot, John Wayne, is assigned to spy on her. They fall in love. When Leigh is denied asylum, Wayne marries her to prevent her deportation. They go to Russia to spread false information. When they return, Wayne is suspected of being a double agent. Leigh helps them escape to Austria.

Janet Leigh is the visual center of the film. Sternberg secretly added some clever elements. For example, during the mid-air refueling scenes, the fighter jets seem to take on the personalities of Leigh and Wayne.

Sternberg finished filming in just seven weeks. But the movie went through many changes and was not released until six years later, in 1957. It was a moderate success.

Macao: 1952

After Jet Pilot, Sternberg immediately started his second film for RKO, Macao. RKO kept strict control over this film. The thriller is set in Macao, a Portuguese colony in China. American drifters Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell get caught up in a plot to trick a corrupt casino owner.

Sternberg's unique style is only seen in a few parts of the film, like a chase scene with hanging fish nets or a feather pillow exploding in a fan. The producers thought his action scenes were not good enough. Another director was called in to re-shoot the main fight scene. Sternberg did not get a new contract with RKO.

Sternberg continued to try to make independent films. He renewed his friendship with Japanese producer Nagamasa Kawakita. They decided to work together in Japan. This led to Sternberg's most personal and final film: The Saga of Anahatan.

Later Career and Legacy

Between 1959 and 1963, Sternberg taught a film class at the University of California, Los Angeles. His students included Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek, who later formed the rock band The Doors. Manzarek said Sternberg was a huge influence on the band.

When he was not working in California, Sternberg lived in a house he built for himself in Weehawken, New Jersey. He collected contemporary art and stamps. He also became interested in the Chinese postal system and learned Chinese. He often served as a judge at film festivals.

Sternberg wrote his autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry (1965). The title came from an early film comedy. The magazine Variety called it a "bitter reflection" on how a master artist could be overlooked. He passed away on December 22, 1969, at age 75, after a heart attack. He was buried in the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Westwood, California.

What Others Said About Him

- Scottish-American screenwriter Aeneas MacKenzie: "To understand what Sternberg is trying to do, you must first know that he only uses visuals. He refuses to get any effect except through how he arranges pictures. That is the main difference between von Sternberg and all other directors."

- American film actress and dancer Louise Brooks: "Sternberg, with his calm way, could look at a woman and say 'this is beautiful about her and I'll keep it... and this is ugly about her and I'll remove it.' He was the greatest director of women ever."

- American actor Edward Arnold: "He might break an actor's ego and crush their unique style... but whatever his methods, he got the best out of his actors."

- American film critic Andrew Sarris: "Sternberg fought against actors having too much freedom until the very end of his career. That fight is likely one reason his career ended sooner."

Filmography

Silent films

- The Salvation Hunters (1925)

- The Exquisite Sinner (1926, lost)

- A Woman of the Sea (1926, also known as The Sea Gull or Sea Gulls or The Woman who loved once, lost)

- Underworld (1927)

- The Last Command (1928)

- The Dragnet (1928, lost)

- The Docks of New York (1928)

- The Case of Lena Smith (1929, lost)

Sound films

- Thunderbolt (1929)

- The Blue Angel (1930)

- Morocco (1930)

- Dishonored (1931)

- An American Tragedy (1931)

- Shanghai Express (1932)

- Blonde Venus (1932)

- The Scarlet Empress (1934)

- The Devil is a Woman (1935)

- Crime and Punishment (1935)

- The King Steps Out (1936)

- Sergeant Madden (1939)

- The Shanghai Gesture (1941)

- The Town (1943, short film)

- Macao (1952)

- Anatahan (1953 also known as The Saga of Anatahan)

- Jet Pilot (1957)

Other projects

- The Masked Bride (1925, directed with Christy Cabanne, uncredited)

- It (1927, directed with Clarence G. Badger, uncredited)

- Children of Divorce (1927, directed with Frank Lloyd, uncredited)

- Street of Sin (1928, directed with Mauritz Stiller, uncredited)

- I, Claudius (1937, unfinished)

- The Great Waltz (1938, directed with Julien Duvivier, uncredited)

- I Take This Woman (1940, directed with W.S. Van Dyke, uncredited)

- Duel in the Sun (1946, directed with King Vidor, uncredited)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Josef von Sternberg para niños

In Spanish: Josef von Sternberg para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |