Justin Martyr facts for kids

Quick facts for kids SaintJustin Martyr |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Theologian, Apologist, and Martyr | |

| Born | AD 100 Flavia Neapolis, Judea |

| Died | 165 (aged 65) Rome, Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church Oriental Orthodoxy Lutheranism Anglicanism |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation for the Causes of Saints |

| Feast | 1 June (Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Anglicanism) 14 April (Roman Calendar, 1882–1969) |

| Patronage | Philosophers

Philosophy career |

| Other names | Justin the Philosopher |

|

Notable work

|

1st Apology |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| School | Middle Platonism |

|

Main interests

|

Apologetics |

|

Notable ideas

|

|

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Justin Martyr (Greek: Ἰουστῖνος ὁ μάρτυς; around AD 100 – around AD 165), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian writer and thinker. He is famous for defending the Christian faith to the Roman emperors.

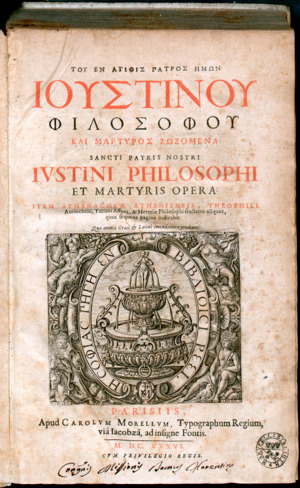

Most of his writings are now lost. However, two of his defenses of Christianity (called "apologies") and a discussion (called a "dialogue") still exist. His most famous work, the First Apology, strongly argued that Christians lived good lives. It used philosophical ideas to try and convince the Roman emperor, Antoninus Pius, to stop harming Christians.

Justin believed that "seeds of Christianity" could be found even before Jesus. He thought that some Greek philosophers, like Socrates and Plato, were like "unknowing Christians" because their ideas showed parts of God's truth.

Justin was killed for his faith, along with some of his students. He is honored as a saint by the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, and in Anglicanism.

Contents

Justin's Life Story

Justin Martyr was born around AD 90-100. His family was Greek, and they lived in Flavia Neapolis (which is now Nablus) near the old city of Shechem in Samaria. He probably didn't know much Hebrew or Aramaic and wasn't very familiar with Judaism. His family might have been pagan, meaning they didn't follow the Jewish or Christian faith.

In one of his writings, Justin explained that his early education didn't satisfy him. He was looking for a belief system that could truly inspire him. He tried learning from a Stoic philosopher, but this teacher couldn't explain God well enough. He then tried a Peripatetic philosopher, but this teacher seemed more interested in money. Next, he met a Pythagorean philosopher who wanted him to learn music, astronomy, and geometry first, which Justin didn't want to do. Finally, he became interested in Platonism after meeting a Platonist thinker in his city.

Later, he met an old man, possibly a Christian, by the sea. This man talked to him about God and said that the words of the prophets were more trustworthy than the ideas of philosophers.

Justin was deeply moved by the old man's words. He decided to leave his old beliefs and philosophical studies behind. He chose to dedicate his life to God. He was also inspired by how early Christians lived simple lives and how bravely martyrs faced death. This convinced him that Christian teachings were morally and spiritually better. From then on, he decided to travel and share Christianity as the "true philosophy."

Justin started wearing the clothes of a philosopher and traveled, teaching about Christianity. During the time of Emperor Antoninus Pius (138–161 AD), Justin came to Rome and opened his own school. Tatian was one of his students.

Later, during the rule of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, Justin had a disagreement with a philosopher named Crescens. Crescens then reported Justin to the authorities. Justin was put on trial with six of his friends, including two slaves he had taught. The judge, Junius Rusticus, ordered them to be beheaded. We don't know the exact year Justin died, but it was likely between 162 and 168 AD, when Rusticus was in charge. The official court record of his trial still exists.

Where Justin's Relics Are

Some churches claim to have parts of Saint Justin's body, known as relics.

The church of St. John the Baptist in Sacrofano, a few miles north of Rome, says it has his relics.

The Church of the Jesuits in Valletta, Malta, also claims to have relics of this important saint from the second century.

There's also a belief that St. Justin's relics are buried in Annapolis, Maryland, in the United States. During a time of trouble in Italy, a noble family who had his remains sent them to a priest in Baltimore in 1873 for safekeeping. They were shown in St. Mary's Church for a while before being put away again. The remains were found again and properly buried at St. Mary's in 1989, with approval from the Vatican.

How Justin Is Honored

In 1882, Pope Leo XIII created special prayers and church services for Justin's feast day. He set it for April 14. However, this date often falls during the main Easter celebrations. So, in 1968, the feast day was moved to June 1. This is the same day he has been honored in the Byzantine Rite (Eastern Christian churches) since at least the 9th century.

Justin is also remembered in the Church of England with a special day called a Lesser Festival on June 1.

Justin's Writings

Justin Martyr's student, Tatian, was the first to mention him in his own writings. Tatian called him "the most admirable Justin." Other early Christian writers like Irenaeus and Tertullian also wrote about Justin and his martyrdom.

A historian named Eusebius of Caesarea wrote a lot about Justin and listed some of his works:

- The First Apology: This was a defense of Christianity written to Emperor Antoninus Pius and the Roman Senate.

- A Second Apology of Justin Martyr: Another defense, also to the Roman Senate.

- The Discourse to the Greeks: A discussion with Greek philosophers about their gods.

- The Dialogue with Trypho: A conversation with a Jewish man about Christianity.

Eusebius also mentioned that Justin wrote other works that are now lost.

The Dialogue with Trypho

The Dialogue was written after the First Apology. The First Apology was written between 147 and 161 AD. In the Dialogue with Trypho, Justin explains that Christianity is the new law for everyone.

Justin's discussion with Trypho is special because it shows some of the disagreements between Jewish and Gentile (non-Jewish) Christians in the second century. It also shows that there were different views on Jewish beliefs and traditions among Christians.

On the Resurrection

A writing called On the Resurrection exists in many pieces. These pieces talk about how the truth of God doesn't need proof, but arguments are needed to convince those who doubt. It explains that the resurrection of the body (coming back to life) is possible and worthy of God. It also says that prophecies support this idea.

Another part of the writing talks about how Jesus's own resurrection and the people he brought back to life prove the idea of resurrection. The writing also says that knowing about the resurrection is a new teaching, different from old philosophical ideas. It connects the idea of resurrection to keeping the body morally pure.

Justin's Role in the Early Church

Some scholars have pointed out that Justin's ideas were influenced by pagan philosophers. Others argue that he was a strong Christian who simply used philosophical ideas to explain his faith.

Justin believed that his teachings were in line with the wider Church. He knew of some disagreements among Christians, for example, about the idea of a "millennium" (a thousand-year reign of Christ). He was willing to accept Jewish Christians as long as they didn't stop Gentile Christians from practicing their faith freely.

Justin was often against Judaism, which was common among church leaders at the time. He saw Jews as a people who had been rejected. Some people say his strong words against Jews contributed to later Christian antisemitism (hatred of Jews). However, his views in the Dialogue with Trypho were milder compared to some later writers.

Justin's Understanding of Christ

Justin believed that Greek philosophers had learned important truths from the Old Testament. He also used the Stoic idea of the "seminal word," which meant that a part of God's reason or "Word" was present everywhere. He connected this "Word" directly to Christ.

Because of this, he even said that Socrates and Heraclitus were Christians, even though they lived before Jesus. He wanted to show that everything good and true that ever existed came from Christ. Old philosophers and law-givers only had a small part of the "Logos" (God's Word), while the whole "Logos" appeared in Christ.

Justin believed that while non-Jewish people were led astray by evil spirits to worship idols, Jews and Samaritans had God's revelation through the prophets and were waiting for the Messiah. He thought that the Jewish law, while having good commands, also had temporary rules (like animal sacrifices, the Sabbath, and food laws) that ended when Christ appeared. Through Christ, God's lasting law was fully revealed. Justin saw Christ's main work as teaching the new doctrine and giving the new law.

The 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia notes that experts disagree on whether Justin's writings about God's nature were his final beliefs or just his thoughts on these matters. Justin wrote that the Logos (Christ) is "different from the Father" but "born from the very substance of the Father." He also said that "through the Word, God has made everything." Justin used the idea of fire to explain that the Logos spreads like a flame without dividing the Father's substance. He also defended the Holy Spirit as part of the Trinity and believed in Jesus's birth to Mary when she was a virgin.

Records of the Apostles

In his First Apology (around 155 AD) and Dialogue with Trypho (around 160 AD), Justin Martyr often referred to written stories about Jesus's life and his sayings. He called these "memoirs of the apostles" (Greek: ἀπομνημονεύματα τῶν ἀποστόλων) or sometimes "gospels" (Greek: εὐαγγέλιον). Justin said these were read every Sunday in the church in Rome.

Justin used the term "memoirs of the apostles" more often than "gospels." However, in one place, he used both terms, making it clear they meant the same thing. He said, "The apostles in the memoirs which have come from them, which are also called gospels, have transmitted that the Lord had commanded..." This shows Justin knew about more than one written gospel. He might have preferred "memoirs of the apostles" to show that these writings were true historical accounts from the apostles.

Justin explained the gospel texts as accurate records of how prophecies came true. He combined these with quotes from the prophets of Israel from the LXX (Greek Old Testament) to prove the Christian message. The importance Justin gave to the prophets' words shows how much he valued the Old Testament.

How Justin's Works Were Put Together

Sources from the Bible

Gospels

Justin used information from the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) in his First Apology and Dialogue. He might have used Matthew directly or used a combination of gospels. It's not clear if he knew or used the Gospel of John. One possible reference to John is a saying about baptism: "Unless you are reborn, you cannot enter into the kingdom of heaven." However, some scholars think Justin got this saying from a baptism service rather than a written gospel.

Justin also used words very similar to those in John 1:20 and 1:28. By calling some writings "memoirs of the apostles" and separating them from writings by their "followers," Justin likely believed that at least two gospels were written by actual apostles.

Revelation

Justin didn't quote from the Book of Revelation directly, but he clearly mentioned it. He named John as its author. He said, "Moreover also among us a man named John, one of the apostles of Christ, prophesied in a revelation made to him that those who have believed on our Christ will spend a thousand years in Jerusalem." This shows Justin saw a difference between prophecy and the gospel stories.

Other Sources

Justin included a section on Greek mythology in his First Apology and Dialogue. He argued that myths about pagan gods were actually copies of prophecies about Christ in the Old Testament. He also had a small section about how philosophers, especially Plato, borrowed ideas from Moses. These two sections might have come from an earlier Christian defense.

Understanding Prophecy

Justin's writings are a great source for understanding how early Christians interpreted Bible prophecies.

Belief in Prophecy

He believed that the truth of the prophets was so strong that it forced people to agree with it. He saw the Old Testament as an inspired guide. He described his own conversion, saying that a Christian philosopher told him: "There were, long before this time, certain men older than all philosophers. They were good and loved by God. They spoke by God's Spirit and foretold events that would happen and are happening now. They are called prophets. Only they saw and told the truth to people. They weren't afraid of anyone or seeking fame. They only spoke what they saw and heard, filled with the Holy Spirit. Their writings still exist, and whoever reads them learns a lot about the beginning and end of things... And what has happened, and what is happening, makes you agree with what they said."

Justin then shared his own experience: "Right away, a flame lit up in my soul; and a love for the prophets, and for those who are friends of Christ, took hold of me. As I thought about his words, I found this philosophy to be the only safe and helpful one."

Prophecies Coming True

Justin listed the following events as examples of Bible prophecies coming true:

- Prophecies about the Messiah and details of Jesus's life.

- The destruction of Jerusalem.

- Non-Jewish people (Gentiles) accepting Christianity.

- Isaiah predicting that Jesus would be born of a virgin.

- Micah mentioning Bethlehem as Jesus's birthplace.

- Zechariah forecasting Jesus entering Jerusalem on a donkey's foal.

Second Coming and Daniel 7

Justin connected the Second Coming of Jesus with the end of the prophecy in Daniel 7. He wrote: "If such great power followed and still follows His suffering, how much greater will be the power that follows His glorious return! For He will come on the clouds as the Son of man, as Daniel foretold, and His angels will come with Him."

The Antichrist

Justin believed that the Second Coming would happen soon after the "man of apostasy," which means the Antichrist, appeared.

Time, Times, and a Half

Justin thought that Daniel's prophecy of "time, times, and a half" was nearing its end. This is when the Antichrist would speak evil words against God.

The Eucharist

Justin's statements are some of the earliest Christian descriptions of the Eucharist (Communion). He wrote: "And this food is called among us Εὐχαριστία [the Eucharist]... For we do not receive these as common bread and common drink. But just as Jesus Christ our Savior became flesh by the Word of God and had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so we have been taught that the food, which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh are nourished by change, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who became flesh."

Editions of Justin's Works

Many different versions and translations of Justin Martyr's writings have been published over the centuries.

Greek texts:

- Egyptian Exploration Society, 4th century

- Thirlby, S., London, 1722.

- Maran, P., Paris, 1742 (reprinted in Migne, Patrologia Graeca, Vol. VI. Paris, 1857).

- Otto, J. C., Jena, 1842 (3rd ed., 1876–1881).

- Krüger, G., Leipzig, 1896 (3rd ed., Tübingen, 1915).

- In Die ältesten Apologeten, ed. G.J. Goodspeed, (Göttingen, 1914; reprint 1984).

- Iustini Martyris Dialogus cum Tryphone, ed Miroslav Marcovich (Patristische Texte und Studien 47, Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, 1997).

- Minns, Denis, and Paul Parvis. Justin, Philosopher and Martyr: Apologies. Edited by Henry Chadwick, Oxford Early Christian Texts. Oxford: OUP, 2009. (This edition includes a critical Greek text and an English translation).

- Philippe Bobichon (ed.), Justin Martyr, Dialogue avec Tryphon, édition critique, introduction, texte grec, traduction, commentaires, appendices, indices, (Coll. Paradosis nos. 47, vol. I-II.) Editions Universitaires de Fribourg Suisse, (1125 pp.), 2003

English translations:

- Halton, TP and M Slusser, eds, Dialogue with Trypho, trans TB Falls, Selections from the Fathers of the Church, 3, (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press)

- Minns, Denis, & Paul Parvis. Justin, Philosopher and Martyr: Apologies. Edited by Henry Chadwick, Oxford Early Christian Texts. Oxford: OUP, 2009.

Georgian translation:

- "Sulieri Venakhi", I, The First and Second Apology of Saint Justin Philosopher and Martyr, translated from Old Greek into Georgian, submitted with preface and comments by a monk Ekvtime Krupitski, Tbilisi Theological Academy, Tsalka, Sameba village, Cross Monastery, "Sulieri venakhi" Publishers, Tbilisi, 2022, ISBN 978-9941-9676-1-0

- "Sulieri Venakhi", II, Saint Justin Martyr's dialogue with Trypho the Jew, translated from Old Greek into Georgian, submitted with preface and comments by a monk Ekvtime Krupitski, Tbilisi Theological Academy, Tsalka, Sameba village, Cross Monastery, "Sulieri venakhi" Publishers, Tbilisi, 2019, ISBN 978-9941-8-1570-6

See also

In Spanish: Justino Mártir para niños

In Spanish: Justino Mártir para niños