Lake Chicago facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Lake Chicago |

|

|---|---|

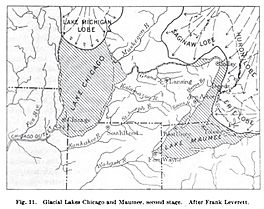

Map of middle stage of glacial Lake Chicago, USGS Report of 1915.

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | North America |

| Group | Great Lakes |

| Lake type | former lake |

| Primary inflows | Laurentide Ice Sheet |

| Primary outflows | Chicago River |

| Basin countries | United States |

| First flooded | 18,000 years before present |

| Max. length | 241 mi (388 km) |

| Max. width | 57 mi (92 km) |

| Average depth | 160 ft (49 m) |

| Residence time | 4000 years in existence |

| Surface elevation | 160 ft (49 m) |

Imagine a giant lake that existed long, long ago, even before humans built cities! That was Lake Chicago. It was a huge prehistoric lake that eventually became what we know today as Lake Michigan.

Lake Chicago was formed by melting glaciers. These huge sheets of ice covered much of North America. As they melted, the water flowed south, creating this massive lake.

Contents

How Lake Chicago Was Formed

The area where the city of Chicago now stands was once covered by warm, shallow seas. This was hundreds of millions of years ago. You can still find proof of these ancient seas. Look for fossils of coral in places like Thornton Quarry in Illinois.

Much later, huge sheets of ice, called polar ice caps, moved across the continent four times. They covered the region with ice more than a mile (1500 m) deep!

As the climate changed, the ice began to melt. The last big ice sheet, called the Wisconsin Glacier, started to retreat. This created a path for the melting water to flow.

The water carved out valleys, like the Des Plaines River Valley. A huge rush of water, known as the Kankakee Torrent, poured through these valleys. This powerful flow eventually left behind the prehistoric Lake Chicago. It was the ancestor of our modern Lake Michigan.

When Lake Chicago Existed

Lake Chicago first started to form about 13,000 years ago. This happened when a part of the glacier, called the Michigan Lobe, moved north. It moved into the area where Lake Michigan is now.

As the glacier retreated, it left behind piles of rock and dirt called moraines. These formed ridges like the Park Moraine in Illinois.

The lake level stayed at about 640 feet (195 m) above sea level for a long time. The ice kept moving north, opening up channels across Michigan. This allowed water from other ancient lakes, like Lake Saginaw and Lake Whittlesey, to drain into Lake Chicago.

Later, the ice moved even further north. This opened up the Mohawk River valley. Water from the Lake Huron and Lake Erie areas then drained through this new path. This left Lake Chicago as a "headwaters lake," meaning it was at the top of its own drainage system.

As the glacier continued to retreat, it set the stage for other large prehistoric lakes in the Lake Michigan area. These included Lake Algonquin and the Nipissing Great Lakes.

How Big Was Lake Chicago?

Lake Chicago was even bigger than Lake Michigan is today! It stretched further south, west, and east. To the west, it reached La Grange, Illinois. To the south, it went past Homewood and Lansing, Illinois.

It completely covered what is now Northwest Indiana. This included cities like Hammond and Gary, Indiana.

As the Wisconsin Glacier kept melting, new paths for the water opened up. These included Niagara Falls and the Saint Lawrence River. When these new outlets formed, the water level in Lake Chicago began to drop.

The lake level dropped in three clear stages. Each time, it fell about 15 to 20 feet (5–6 m). Eventually, the old outlet to the southwest dried up. The Des Plaines River then started to flow into the basin that became Lake Michigan.

Ancient Shorelines and Outlets

The first way Lake Chicago drained was to the southwest. The water flowed through the Des Plaines River valley. From there, it went down the Illinois River all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.

The highest ancient beach left by Lake Chicago is called the Glenwood Shoreline. It is about 55 to 60 feet (17–18 m) above the current level of Lake Michigan.

There are two other ancient beaches. These formed when the Des Plaines outlet was no longer used. Water started flowing through other outlets to the north and east. These beaches are the Calumet Shoreline, about 35 to 40 feet (11–12 m) above Lake Michigan, and the Tolleston Beach, about 20 to 25 feet (6–8 m) above the current lake.

The channel where the water flowed out was more than 1 mile (1.6 km) wide. It cut through layers of rock and glacial deposits. The distinct beaches we see today likely formed because these rock layers broke away quickly. This caused the lake level to drop suddenly. If the outlet had eroded slowly, the beaches would not be so clear.

Along the eastern side of Lake Michigan, most of Lake Chicago's old beaches have been worn away by erosion. The best remaining parts are found at the southern tip of Lake Michigan in Indiana.

What Lake Chicago Left Behind

Lake Chicago covered only a narrow strip of land on the south and east sides of modern Lake Michigan. In some areas, the ancient lake bed extends 10 to 25 miles (16 to 40 km) inland. This area is mostly fine sand.

Strong winds along the east shore of Lake Michigan have created large sand dunes. These dunes have buried the older glacial beaches and lake beds.

Today, you can still see evidence of the huge amounts of sand left behind by Lake Chicago. For example, Northern Indiana has the famous Indiana Dunes.

Many roads and trails in the Chicago area follow these ancient beach lines or sand ridges. For instance, Ridge Road in Homewood, Illinois, follows one of these old lines. Blue Island, Illinois, and Stony Island were actually islands when Lake Chicago's water level was higher.

Images for kids

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |