Larry Doby facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Larry Doby |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

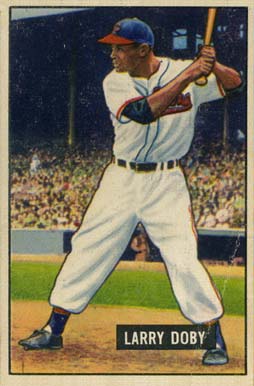

Doby with the Indians in 1953

|

|||

| Center fielder / Manager | |||

| Born: December 13, 1923 Camden, South Carolina |

|||

| Died: June 18, 2003 (aged 79) Montclair, New Jersey |

|||

|

|||

| Professional debut | |||

| NgL: 1942, for the Newark Eagles | |||

| MLB: July 5, 1947, for the Cleveland Indians | |||

| NPB: June 30, 1962, for the Chunichi Dragons | |||

| Last appearance | |||

| MLB: June 26, 1959, for the Chicago White Sox | |||

| NPB: October 9, 1962, for the Chunichi Dragons | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .288 | ||

| Home runs | 273 | ||

| Runs batted in | 1,099 | ||

| Managerial record | 37–50 | ||

| Winning % | .425 | ||

| NPB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .224 | ||

| Home runs | 10 | ||

| Runs batted in | 35 | ||

| Teams | |||

Negro leagues

Major League Baseball

Nippon Professional Baseball

As manager

|

|||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

|

|||

| Induction | 1998 | ||

| Election Method | Veterans Committee | ||

Lawrence Eugene Doby (December 13, 1923 – June 18, 2003) was an American professional baseball player. He played in the Negro leagues and later in Major League Baseball (MLB). Doby made history as the second black player to break baseball's color barrier. He was also the first black player in the American League.

Born in Camden, South Carolina, Doby was a talented athlete. In high school in Paterson, New Jersey, he excelled in three sports. He even earned a basketball scholarship to Long Island University. At just 17, he started his professional baseball journey with the Newark Eagles. This team was part of the Negro leagues.

Doby served in the United States Navy during World War II. After the war, he returned to baseball in 1946. With his teammate Monte Irvin, he helped the Eagles win the Negro League World Series.

In July 1947, just three months after Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers, Doby signed with the Cleveland Indians. This made him the first black player in the American League. He was also the first player to go directly from the Negro leagues to the major leagues. Doby became a seven-time All-Star center fielder. In 1948, he and teammate Satchel Paige were the first African-American players to win a World Series championship. The Indians won the title that year.

In 1954, Doby helped the Indians win 111 games and the AL pennant. He led the AL in RBIs and home runs. He also finished second in the AL Most Valuable Player (MVP) voting. After his time with the Indians, he played for the Chicago White Sox, Detroit Tigers, and Chunichi Dragons in Japan. He retired as a player in 1962.

Later, Doby became the second black manager in the major leagues. He managed the Chicago White Sox in 1978. In 1995, he took on a role in the AL's main office. He also worked as a director for the New Jersey Nets basketball team. In 1998, he was chosen for the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Larry Doby passed away in 2003 at age 79.

Contents

- Larry Doby's Early Life and Baseball Dreams

- Playing in the Negro Leagues and Serving in World War II

- Larry Doby's Major League Baseball Career

- Larry Doby's Managerial and Executive Roles

- Larry Doby: The "Second Man" to Break Barriers

- Larry Doby's Hall of Fame Recognition

- Larry Doby's Legacy

- See also

Larry Doby's Early Life and Baseball Dreams

Larry Doby was born in Camden, South Carolina. His father, David Doby, was a horse groomer and played semi-pro baseball. Sadly, David drowned when Larry was young. Larry's mother moved to Paterson, New Jersey. Larry stayed in Camden with his grandmother and then with other relatives.

He went to Jackson School, which was a segregated school. His first chance to play organized baseball came at Boylan-Haven-Mather Academy. A local baseball expert, Richard Dubose, taught Doby some of his first baseball lessons. Doby remembered playing baseball with worn-down broom handles for bats. He said, "Growing up in Camden, we didn't have baseball bats. We'd use a tree here, a tin can there, for bases."

At 14, Doby moved to Paterson, New Jersey, to live with his mother. At Paterson Eastside High School, he was a star in many sports. He played baseball, basketball, and football. He also ran track. Once, his football team won a state championship. They were invited to play in Florida. But Doby, the only black player, was not allowed to play. His teammates chose not to go on the trip to support him.

During summer breaks, Doby played baseball with a black semi-pro team called the Smart Sets. He played with Monte Irvin, who would also become a Hall of Famer. He also played a short time for the Harlem Renaissance, a professional basketball team. After high school, he got a scholarship to play basketball at Long Island University Brooklyn (LIU). He chose LIU to stay close to his girlfriend, Helyn Curvy, who he later married.

Before starting at LIU, Doby joined the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League (NNL) in 1942. He was only 17. He used the name "Larry Walker" to keep his amateur status for college. He later transferred to Virginia Union University.

Playing in the Negro Leagues and Serving in World War II

Larry Doby joined the Newark Eagles in 1942. He was paid $300. His first professional game was at Yankee Stadium. He had a great batting average of .391 in his first 26 games. He remembered playing against famous players like Josh Gibson. Gibson challenged Doby's hitting skills, and Doby proved himself.

Doby's baseball career was put on hold for two years. He served in the United States Navy during World War II. He played on an all-black baseball team in the Navy. He had a .342 batting average against teams with white players, including some major leaguers. He served in different Navy locations, including the Pacific Ocean. While serving, he heard about Jackie Robinson signing a minor league contract. This gave Doby hope for black players in Major League Baseball.

He was discharged from the Navy in January 1946. That summer, he married Helyn Curvy. After playing in Puerto Rico, Doby rejoined the Eagles. He became an All-Star and batted .360. His team, the Eagles, won the Negro World Series in 1946. They beat Satchel Paige and the Kansas City Monarchs. Doby hit .372 in the Series. Many people in the Negro leagues thought Doby or Monte Irvin would be the first to break the MLB color barrier. Doby said he never dreamed of playing in the MLB because of segregation.

Larry Doby's Major League Baseball Career

Breaking the Color Barrier in the American League (1947)

Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck wanted to integrate baseball. He looked for a talented black player who could handle the pressure. A reporter suggested Doby. Veeck's scout also gave Doby a good review. Veeck decided to sign Doby directly from the Negro leagues.

On July 3, Veeck bought Doby's contract from the Newark Eagles for $15,000. Veeck wanted to introduce Doby carefully to Cleveland fans. On July 5, 1947, Doby made his debut. He was the second black player in the majors after Jackie Robinson. Veeck even hired police officers to go with Doby to Comiskey Park.

Doby met his new teammates that day. He recalled, "I walked down that line, stuck out my hand, and very few hands came back in return." Some teammates turned their backs on him. Only Joe Gordon welcomed him and played catch with him. Gordon became one of Doby's closest friends on the team.

Doby entered the game as a pinch-hitter and struck out. After the game, Doby had to stay in a separate, segregated hotel. This was a pattern he faced in many cities throughout his career. The next day, Doby started at first base. He had to borrow a mitt from a White Sox player because his own teammates wouldn't lend him one. Doby got his first major league hit and an RBI that day.

Some people, like former player Rogers Hornsby, criticized Doby. Hornsby said Doby wasn't good enough for semi-pro baseball. In his first year, Doby hit .156 in 29 games. He talked with Jackie Robinson on the phone often. They encouraged each other to stay strong and not cause trouble. After his rookie season, Doby played professional basketball briefly. He was the first black player in that league.

Becoming a Star with the Cleveland Indians (1948–1955)

In 1948, Doby went to his first spring training with the Indians. He, Satchel Paige, and Minnie Miñoso had to stay with a local black family. They couldn't stay at the team hotel. Doby worked hard to improve his outfield play. He got help from former manager Tris Speaker. In an exhibition game, Doby hit a huge home run. This showed everyone he belonged on the team. That year, he played in 121 games and hit .301 with 14 home runs and 66 RBIs. Opposing teams often used racial slurs against Doby.

Doby was key to Cleveland's World Series victory. In Game 4, he hit the first home run by a black player in World Series history. A famous photo showed Doby hugging white teammate Steve Gromek. Doby said this picture was more meaningful than the home run itself. It showed a moment of true friendship. The Indians won the Series in six games. Doby batted .318. After the win, Doby had a parade in his hometown. He and his wife tried to buy a home in a white neighborhood but faced resistance. The Paterson city mayor helped them buy their dream home.

In 1949, Doby was chosen for his first MLB All-Star Game. He joined Jackie Robinson and others as the first black players in the All-Star Game. His home run and RBI numbers grew. By 1950, he was considered one of the best center fielders. He had a career-best batting average of .326 and 102 RBIs. He finished eighth in AL MVP voting. Cleveland signed him to a better contract. He was named Cleveland Baseball Man of the Year, the first black player to receive this award.

In 1951, Doby's numbers dropped a bit due to injuries. He had a muscle tear and a groin pull. Some in the press criticized him, calling him a "loner." They thought racial prejudice affected him. Doby said opposing pitchers were intentionally throwing at him because he was black. Statistics showed black players were hit by pitches much more often.

Before the 1952 season, Doby worked with an Olympic athlete to strengthen his legs. He still had some injuries, but on June 4, 1952, he hit for the cycle. This means he hit a single, double, triple, and home run in the same game. He led the AL in home runs (32) and finished second in RBIs (104).

In 1953, Doby got a pay raise. He hit 29 home runs and 102 RBIs. In 1954, he was named an All-Star for the sixth time. The game was in Cleveland. Doby hit a pinch-hit solo home run to tie the game. It was the first All-Star Game home run by a black player. Doby helped the Indians win a team-record 111 games and the AL pennant. He led the AL with 32 home runs and a career-high 126 RBIs. He finished second in AL MVP voting. However, the Indians lost the 1954 World Series to the New York Giants.

In 1955, Doby was selected for his seventh and final All-Star Game. His leg injuries were severe. He finished the season with 26 home runs and 75 RBIs. Some people in Cleveland were ready for Doby to leave. A columnist wrote that Doby was "morose, sullen, and upon occasion, downright surly." Doby responded, "I was looked on as a Black man, not as a human being." He felt a responsibility to other black players.

Playing for Other Teams (1956–1960)

After nine seasons, Doby was traded to the Chicago White Sox in October 1955. The White Sox needed a power hitter. Doby helped them sweep the Yankees in a four-game series for the first time since 1945. He hit six home runs during that winning streak. He finished 1956 with 24 home runs and 102 RBIs.

In 1957, Doby helped pitcher Bob Keegan throw a no-hitter with a great catch. He hit 14 home runs and had 79 RBIs that year. In 1958, he was traded back to the Cleveland Indians. He played 89 games, hitting .289 with 13 home runs. In 1959, he was traded to the Detroit Tigers. He played only a few games before being sold back to the White Sox.

After 21 games with the White Sox, he was sent to their minor league team, the San Diego Padres. He fractured his ankle sliding into third base. Due to nagging injuries, Doby did not make the White Sox roster in 1960. He tried to play for the Toronto Maple Leafs but was released after X-rays showed bone damage in his ankle.

Larry Doby ended his 13-year major league career with a .283 batting average. He had 1,515 hits, 253 home runs, and 970 RBIs. He played 1,146 of his 1,533 games with the Indians. Doby said, "I played against great talent in the Major Leagues and I played against great talent in the Negro Leagues. I didn't see a lot of difference."

Playing Baseball in Japan (1962)

In 1962, Doby came out of retirement. He became one of the first Americans to play professional baseball in Japan. He and Don Newcombe, a former teammate, signed with the Chunichi Dragons. After the season, Doby returned to the U.S.

Larry Doby's Managerial and Executive Roles

After retiring as a player, Doby became a scout for the Montreal Expos in 1969. He also worked as a minor league instructor. He was a batting coach for the Expos from 1971 to 1973 and again in 1976. He also managed teams in Venezuela during winter league seasons.

In 1974, Doby returned to the Indians as a first base coach. When the manager was fired, Frank Robinson became the club's player-manager. He was baseball's first black manager.

In 1976, Bill Veeck bought the White Sox again and hired Doby as their batting coach. The team's hitting improved greatly under Doby. On June 30, 1978, Veeck made Doby the White Sox manager. At 53, Doby became the second black manager in the major leagues. He said, "It's so nice to work for a man like Bill Veeck. You just work as hard as you can, and if the opportunity arises, you will certainly get the opportunity to fulfill your dreams."

The White Sox had a 34–40 record when Doby took over. He won his second game as manager. The team finished the season with a 71–90 record, including 37–50 under Doby. This was Doby's only time as a major league manager. Veeck later reassigned Doby to batting coach. Doby resigned in October 1979.

After leaving baseball, Doby worked for the National Basketball Association's New Jersey Nets. He was their director of communications and community affairs from 1980 to 1990. In 1995, he became a special assistant to the American League president.

Larry Doby: The "Second Man" to Break Barriers

The New York Times wrote that Larry Doby is often forgotten because he was "second." Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier first in the National League. But Larry Doby integrated all the American League ballparks. He did it with "class and clout."

A Sports Illustrated editorial pointed out that Doby faced the same challenges as Robinson. But he didn't get the same media attention or support. Writer Scoop Jackson said that in America, those who don't come first sometimes get lost. Doby said, "Jackie got all the publicity for putting up with it (racial slurs). But it was the same thing I had to deal with. ..... Nobody said, 'We're gonna be nice to the second Black.'"

Doby was one of the pallbearers at Robinson's funeral. Fellow Hall of Famer Joe Morgan said Doby admired Robinson and was never jealous. Former teammate Al Rosen believed Doby had an even harder time than Robinson. Robinson was college-educated and had played in Triple-A. Doby came from the Negro leagues and had to learn a new position. Rosen said, "I don't think he has gotten the credit he deserves."

Doby faced many unfair situations. Once, an opposing shortstop spat tobacco juice on him while he was sliding into second base. Doby called it the worst injustice he faced on the field. He also dealt with racial slurs and even death threats. He remembered how the insults from segregated sections of the stands motivated him. He said, "I felt like a quarterback with 5,000 cheerleaders calling his name."

In 1997, the Indians honored Doby by naming a street after him. A columnist wrote that Doby's pioneering journey was just like Robinson's. Doby threw out the ceremonial first pitch at the 1997 Major League Baseball All-Star Game. This game was held in Cleveland to mark 50 years since Robinson broke the color barrier. It was also 50 years and 3 days since Doby became the first black player in the American League.

Larry Doby's Hall of Fame Recognition

|

|

| Larry Doby's number 14 was retired by the Cleveland Indians in 1994. |

Larry Doby was elected into the National Baseball Hall of Fame on March 3, 1998. He was 74 years old. He said, "This is just a tremendous feeling. It's kind of like a bale of cotton has been on your shoulders, and now it's off." He got the news from fellow Hall of Famer Ted Williams. Gene Mauch, a former manager, said Doby and Jackie Robinson were special people to go through what they did.

Doby was inducted into the Hall of Fame on July 26, 1998. He was the first person born in South Carolina to be elected. He was also the last of four players to play in both a Negro league and MLB World Series to be inducted. The others were Satchel Paige, Monte Irvin, and Willie Mays.

Larry Doby's Legacy

Larry Doby and his wife, Helyn, had five children. They also had grandchildren and great-grandchildren. When the Dobys moved to Montclair, New Jersey, Yogi Berra and his wife became their neighbors and friends. Doby had a kidney removed in 1997 due to cancer. Helyn, his wife of 55 years, passed away in 2001 from cancer.

Larry Doby died on June 18, 2003, at his home in Montclair, New Jersey. He was 79 years old and had been battling cancer. President George W. Bush released a statement saying Doby was "a good and honorable man, and a tremendous athlete and manager." He noted Doby's influence on baseball and his role in the 1948 World Series win.

MLB Commissioner Bud Selig said Doby "endured the pain of being a pioneer with grace, dignity, and determination." He also highlighted Doby becoming the second African-American manager. Former MLB Commissioner Fay Vincent said Doby's role in history was recognized "slowly and belatedly." He added that Doby was "every bit as deserving of recognition as Jackie."

Doby was inducted into the Indians Hall of Fame in 1966. He was also inducted into the South Carolina Hall of Fame in 1973 and the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2010. On August 10, 2007, the Indians honored Doby by wearing his number 14 on their uniforms. In 2012, a street next to the Indians' stadium was renamed "Larry Doby Way." In 2015, a life-sized bronze statue of Doby was unveiled outside the stadium.

The city of Paterson, New Jersey, renamed a baseball field "Larry Doby Field" in 2002. The Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center has a section named the Larry Doby Wing. Doby remembered Yogi Berra as one of the first opposing players to talk to him during games.

In 2011, the U.S. Postal Service announced that Doby would be on a postage stamp in 2012. He was one of four baseball players featured. In 2013, Doby was honored for his service in the U.S. Navy during World War II. In 2022, a service area on the Garden State Parkway in New Jersey was renamed the Larry Doby Service Area.

See also

- List of Negro league baseball players

- List of first black Major League Baseball players

- List of Negro league baseball players who played in Major League Baseball

- American expatriate baseball players in Japan

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball players to hit for the cycle

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs scored leaders