Leicester Abbey facts for kids

Low walls laid out on the general plan of Leicester Abbey, which was established during excavations in the 1920s and 1930s.

|

|

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | The Abbey of St Mary de Pratis, Leicester |

| Order | Augustinian Canons |

| Established | 1143 |

| Disestablished | 1538 |

| Dedicated to | The Assumption of the Virgin Mary; and St Mary de Pratis: St. Mary of the Meadows |

| Diocese | Diocese of Lincoln |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Robert le Bossu, Earl of Leicester |

| Important associated figures |

|

| Site | |

| Location | Leicester |

| Coordinates | 52°38′56″N 1°08′13″W / 52.648948°N 1.13687°W |

| Visible remains | Low walls indicating the plan of the abbey and the ruins of Cavendish House. |

|

Listed Building – Grade I

|

|

| Official name: Abbey Ruins; Cavendish House; Abbot Penny's Wall | |

| Designated: | 5 January 1950 |

| Reference #: | 1074051; 1074052; 1361406 |

| Official name: Leicester abbey and 17th century mansion and ornamental gardens | |

| Designated: | 18 July 1995 |

| Reference #: | 1012149 |

The Abbey of Saint Mary de Pratis, also known as Leicester Abbey, was a religious house in Leicester, England. It was founded in the 12th century by Robert de Beaumont, 2nd Earl of Leicester. The abbey became the richest religious place in Leicestershire.

Over time, the abbey received many gifts and donations. It gained control over many churches across England. It also owned a lot of land and several manors. Leicester Abbey even had a smaller, dependent house called Cockerham Priory in Lancashire.

The abbey became wealthy thanks to special permissions from both the English Kings and the Pope. For example, it did not have to send people to parliament. It also did not have to pay tithe (a type of tax) on some of its land and animals.

Even with its wealth, the abbey started having money problems in the late 1300s. It had to rent out its lands. The financial situation got worse in the 1400s and early 1500s. This was partly because some of the abbots (the leaders of the abbey) were not good at managing money. By 1535, the abbey's debts were bigger than its income.

About 30 to 40 canons lived at the abbey. They were sometimes called Black Canons because of their clothes: a white habit and a black cloak. One famous canon, Henry Knighton, wrote a Chronicle while living at the abbey in the 14th century.

In 1530, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey died at the abbey. He was traveling south to face a trial for treason. A few years later, in 1538, the abbey was closed down during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. It was quickly pulled down, and its stones were used to build other structures in Leicester. A large house, later known as Cavendish House, was built on the abbey's site. This house was destroyed by fire in 1645 during the English Civil War.

Part of the abbey's land was given to Leicester Town Council in 1882. It became Abbey Park, opened by The Prince of Wales. The rest of the land, including the abbey's site and the ruins of Cavendish House, was given to the council in 1925. After archaeological digs, it opened to the public in the 1930s. The exact location of the abbey was lost after it was demolished. It was only found again during excavations in the 1920s and 1930s. Today, Leicester Abbey is a protected scheduled monument and a Grade I Listed site.

Contents

History of Leicester Abbey

How the Abbey Started

Leicester Abbey was founded during a time when many monasteries were being built in Europe. Most of England's monasteries were started in the 11th and 12th centuries. Wealthy people often funded these monasteries. They hoped the monks would pray for their souls and allow them to be buried there.

Leicester Abbey followed the Augustinian tradition. The monks, called canons, followed the rules of Saint Augustine. They were known as Black Canons because of their white habit and black cloak. Unlike some monks who lived isolated lives, Augustinian Canons were involved in public ministry.

Robert le Bossu, 2nd Earl of Leicester, founded Leicester Abbey in 1143. It was dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. Robert had already founded Garendon Abbey in Leicestershire in 1133.

Robert's father had started a college of canons called The College of St Mary de Castro in Leicester. The new abbey took control of this college and its churches in Leicester. Robert also gave the abbey many churches in other counties. The abbey also gained the manor of Asfordby and the manor of Knighton.

The Earls of Leicester continued to support the abbey. Petronilla de Grandmesnil, the wife of Robert's son, paid for the building of the abbey's Great Choir. Her husband gave 24 virgates (about 720 acres) of land at Anstey.

In 1148, Pope Eugene III allowed the abbey to not pay tithe on its new land and animals. This was allowed if the abbots were chosen fairly. Also, people who donated money could be buried there, even if they had been excommunicated.

The Abbey in the 1300s

Even though it was a religious house, soldiers attacked the abbey in 1326. They were from the Earl of Lancaster's army. They took property belonging to Hugh le Despenser, 1st Earl of Winchester, which was stored at the abbey.

Under Abbot William Clowne (1345–1378), the abbey grew richer. It gained more lands, including the manors of Ingarsby and Kirkby Mallory. Abbot Clowne was friends with King Edward III. He used this friendship to get more special rights for the abbey. For example, it did not have to send people to Parliament. However, by the late 1300s, the abbey's income started to drop.

During this time, canon Henry Knighton lived at the abbey. He wrote his Chronicle. It described his own experiences from 1377 to 1395. It also included historical events from 1066 to 1366. Knighton wrote about the impact of John Wycliffe and the Lollards.

His chronicle is important for its detailed account of the Black Death in Leicester. He wrote about how the plague affected food prices, wages, and the number of workers. He also recorded how many people died in each parish in Leicester. He found that one-third of Leicester's population died from the disease. Knighton believed the deaths of canons at the abbey were a punishment for choosing unsuitable people for religious roles. His chronicle was not published until 1652.

The Abbey in the 1400s

In the 1400s, the abbey began to rent out its land. This was likely a way to deal with its falling income. By 1477, only the main lands in Leicester, Stoughton, and Ingarsby were still farmed directly by the abbey.

Philip Repyngdon was Abbot of Leicester Abbey from 1393 to 1405. He then became "Chaplain and Confessor" to King Henry IV. Later, he became Bishop of Lincoln and a Cardinal.

Richard of Rothely, Repyngdon's successor, tried to remove the abbey from the Bishop of Lincoln's control. He feared Repyngdon would interfere. It is not clear if the Pope agreed to this. Repyngdon also asked the Pope, who confirmed that Leicester Abbey was still under his control.

Under Abbot William Sadyngton (1420–1442), the abbey's situation worsened. In 1440, William Alnwick, Bishop of Lincoln, visited. He found that the number of canons had dropped from 30-40 to just 14. The number of boys in the almonry (a school for poor boys) fell from 25 to 6. Sadyngton was accused of misusing money and not showing the abbey's accounts. He was also said to keep many servants and even practice magic.

Despite these issues, the abbey seemed financially stable. Its buildings had been rebuilt, and it had a large yearly income of £1180. Bishop Alnwick did not take strong action against Sadyngton. He ordered the number of canons to increase to 30 and the boys in the almonry to 16. He also ordered proper accounts to be kept.

The Abbey in the 1500s

In 1518, William Atwater, Bishop of Lincoln, inspected the abbey. Abbot Richard Pescall was accused of mismanaging money. He was also thought to be too old for his duties. Pescall had too many dogs, which roamed freely. The Bishop also complained that the boys in the almonry were not being taught properly.

A visit in 1521 by Bishop Atwater's successor, John Longland, showed no improvement. Abbot Pescall rarely attended church services. When he did, he brought his jester, who disturbed the services. The canons also behaved badly, eating and drinking at wrong times. They often left the abbey to visit town pubs and go hunting. The abbey was also deeply in debt. The Bishop appointed two people to manage the abbey's money.

The Chancellor of Lincoln Diocese visited in 1528. Things were still bad. The abbot was not attending services and ate alone. He also had too many servants. The 24 canons still left the abbey often without good reason.

Bishop Longland decided to remove Abbot Pescall. Pescall tried to keep his position by sending gifts to Thomas Cromwell. Bishop Longland then constantly interfered with the abbey's affairs. Abbot Pescall finally resigned five years later. He was given a pension of £100 a year. Pescall continued to complain to Thomas Cromwell about the abbey and his pension.

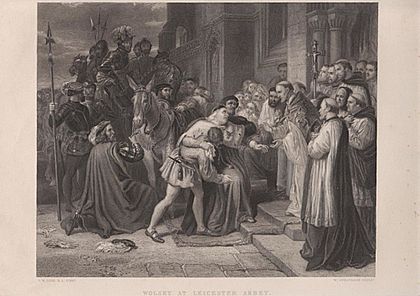

During Abbot Pescall's time, in 1530, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey visited the abbey. Wolsey was a powerful minister for King Henry VIII. He lost the King's favor after failing to get permission for Henry to divorce Katherine of Aragon. On November 4, 1530, Wolsey was arrested for treason.

While traveling from Yorkshire to London, he fell ill. He arrived at Leicester Abbey on November 26, saying, "Father abbott, I ame come hether to leave my bones among you." Wolsey died on November 30 and was buried in the abbey's church.

By the time Pescall was removed, the abbey's finances were very bad. It was the richest monastery in Leicestershire, with an income of £951 in 1534. But it owed £1,000. John Bourchier became the last abbot in 1534. By 1538, he had reduced the debt to £411. Bourchier was not a canon at the abbey before becoming abbot. He likely got the job through his connections with Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII's chief adviser.

In 1527, King Henry VIII asked Pope Clement VII to end his marriage to Katherine of Aragon. The Pope refused. This led to the English Reformation, where Henry broke away from the Pope's authority. Henry became the head of the church in England. All religious figures had to support the King's new power. Abbot Bourchier and the 25 canons at Leicester Abbey agreed to this on August 11, 1534. This saved the abbey from being closed immediately.

Thomas Cromwell, the King's chief minister, wanted the wealth of English monasteries. They owned about a quarter of all the land in England. Starting in 1534, Cromwell had all monasteries inspected. Their wealth was recorded, along with reports of bad behavior. These reports were put into books called the Valor Ecclesiasticus.

Abbot Bourchier tried to gain Cromwell's favor to protect his abbey. In 1536, he sent Cromwell £100 and gifts of sheep and oxen. But it did not work. Cromwell convinced King Henry that monasteries were immoral. Between 1536 and 1541, all monasteries were closed down. Their land, property, and wealth went to the King. Leicester Abbey was finally given to the crown and closed in 1538.

After the Abbey Closed

After it closed in 1538, most of the abbey buildings were torn down within a few years. Only the main gatehouse, boundary walls, and farm buildings were left.

The last abbot, John Bourchier, received a large pension of £200 a year. This was the largest pension in the Diocese of Lincoln. However, payments did not last long. In 1552, during the reign of King Edward VI, all pensions over £10 were stopped due to the country's poor finances.

Bourchier managed to adapt his beliefs to stay in the church's hierarchy. He was considered for a bishop position twice. He then served as a rector (a type of priest) at Church Langton from 1554. This position was financially rewarding.

In 1554, Bourchier was close to becoming a Bishop under Queen Mary. But Mary died, and her sister, Queen Elizabeth, became queen. Elizabeth was Protestant, unlike Mary, who was Catholic. Elizabeth refused to appoint Mary's chosen candidates for bishop roles.

Bourchier could not accept Queen Elizabeth's new laws about the church. So, he decided to keep a low profile. By 1570, his disobedience was noticed, and he lost his position. In 1571, Bourchier sold his £200 a year pension for £900. He then quietly left England, likely for France or Flanders. He was a wealthy but very old man, wanted by the state. He lived quietly abroad and is thought to have lived until at least 1577, when he would have been around 84 years old.

Cavendish House: A New Home on Old Ruins

After the monasteries were closed, Henry VIII began to rent out the newly acquired land. In 1539, Leicester Abbey was leased to Dr. Francis Cave. During this time, the abbey was quickly pulled down. Its stones were sold for building in Leicester.

Henry VIII sold off some religious properties to raise money for wars. Later, these lands were given to important families who supported the King. These former religious sites often became large country homes. Examples include Calke Abbey and Syon House.

Leicester Abbey followed this pattern. Dr. Cave's lease ended in 1551. King Edward VI then gave the abbey to William Parr, 1st Marquess of Northampton. Much of the abbey stone was used to build a new mansion for the Marquess on the site.

The Marquess only owned the abbey for two years. After supporting Lady Jane Grey, his lands were taken away when Mary I became Queen. Mary gave the abbey and mansion to her Catholic supporter, Edward Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings of Loughborough. However, he also lost favor when Elizabeth I became Queen.

The abbey was sold to Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, in 1572. Then it went to his brother, Sir Edward Hastings, in 1590. Sir Edward is thought to be the first owner to live there permanently. He lived in the gatehouse while the site was developed.

Sir Edward's son Henry sold it in 1613 to William Cavendish, 1st Earl of Devonshire. The mansion built on the site became known as Cavendish House. The 1st Earl planned for it to be his main home. He began to greatly expand the mansion. However, after his death, his family decided to use Chatsworth House as their main home. Cavendish House was then only used as a stop on the way to London.

In 1638, Cavendish House became a Dower house for Christiana Cavendish, the widow of the 2nd Earl of Devonshire.

In 1645, during the English Civil War, King Charles I and his Royalist forces used the house after capturing Leicester. When the Royalists left, the house was looted and burned. Cavendish House was never repaired.

The Cavendish family sold the abbey land in 1733. By then, Cavendish House was in ruins, and the land was used for farming. In the 1800s, the land belonged to the Earls of Dysart. Lionel Tollemache, 8th Earl of Dysart, sold the land east of the River Soar in 1876. This allowed Leicester Town Council to work on flood prevention. Part of this land became Abbey Park, which opened in 1882.

The remaining 32 acres of the abbey land, including the abbey's site and Cavendish House, were given to Leicester Council in 1925 by William Tollemache, 9th Earl of Dysart. Part of Cavendish House had to be pulled down because it was unsafe. About six and a half years later, the area opened to the public as part of Abbey Park.

Important Burials at the Abbey

- Petronilla de Grandmesnil, Countess of Leicester

- Robert de Beaumont, 2nd Earl of Leicester

- Stephen de Segrave

- Sir Gilbert de Segrave, son of Stephen de Segrave

- Robert de Beaumont, 4th Earl of Leicester

- Thomas Wolsey

Exploring the Abbey: Archaeological Discoveries

The first digs at the abbey happened in the 1600s. Christiana Cavendish, the Dowager Countess, told her gardener to look for Cardinal Wolsey's body and abbey relics. Not much was found.

Since there were no buildings left above ground, the abbey's exact location was lost. In the 1840s, James Thompson tried to find the abbey church but failed. In the 1850s, the Leicester Architectural and Archaeological Society also tried but found no trace. Another attempt before 1925 also failed.

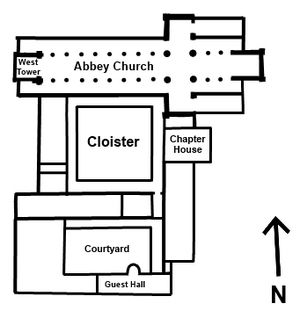

Between 1925 and the 1930s, many archaeological excavations took place. By 1930, the abbey church and many other buildings were finally located. The architect, William Bedingfield, decided to mark the abbey's layout with low stone walls. Since the abbey's stone had been taken, only trenches remained from the old foundations. These trenches were not always clear to early excavators.

In 2002, the University of Leicester Archaeological Services dug where the abbey's kitchens were thought to be. They found the north and south walls and a brick oven from the 1400s or 1500s. This confirmed it was the kitchens. In 2003, they dug a larger area. They found the southwest corner of the building and a second oven. This oven contained charcoal, wheat, barley, fish bones, and hazelnuts. A drain found in the 1930s dig was also located. It contained small bones, fish scales, and rat bones.

These digs confirmed the kitchen was a square building, about 11.88 meters (39 feet) wide. Its walls were thick, between 1.32 and 1.74 meters (4.3 to 5.7 feet). The ovens in the corners suggest the room was octagonal inside. This is similar to the kitchens at Glastonbury Abbey.

From 2000 to 2008, the abbey ruins were used for training archaeology students from the University of Leicester.

Understanding the Abbey's Layout

The archaeological digs helped historians figure out the abbey's layout. This layout was then marked with low stone walls in the 1920s and 1930s. The abbey church was built on raised land and was likely very decorated. It had a tower at the west end, which was the main entrance. It also had two large transepts (parts that stick out) and smaller side chapels.

The cloister (an open courtyard) was south of the church. Three buildings surrounded it. The west building had a "lavatorium" (for washing) and a vaulted undercroft (for storage). The abbot's living quarters were probably on the first floor. The east building had the chapterhouse, a small room (perhaps a library), another undercroft, and a corridor called the Slype leading to the graveyard. The canons' dormitory and communal latrine were on the first floor. The south building had another undercroft, a warming house with a large fire, and the refectory (dining hall) on the first floor.

South of the cloisters were three more buildings around a cobbled courtyard. The western building of this courtyard held the abbey's kitchens. Southeast of this courtyard was a large, separate building. This was likely the "guest hall," with a small projection that might have been an oriel window.

The abbey was inside a large walled area. The original walls were made of sandstone in the 1200s. They had corner towers and smaller towers along their length. Much of this wall was taken down when the area was made larger in the early 1500s. This work was likely done under Abbot John Penny, and the remaining wall is now called "Abbot Penny's Wall." This new wall was built with red brick instead of stone. It has 44 different patterns and symbols made with black bricks. These include family symbols, simple designs, and religious symbols.

You entered the abbey area through an outer gateway on the north wall. This led to a 60-meter (about 200-foot) long "halt-way" with stone walls. At the south end was the abbey's main Gatehouse. The original gatehouse was a single-story building with two lodges. It was later made bigger, measuring 21 by 8.5 meters (69 by 28 feet). It had round towers at each corner, likely containing stairs, and a couple of stories above the gate. A small, second kitchen was probably to the west of the gatehouse.

On the eastern side of the abbey area was the infirmary. This was a hospital for sick or elderly canons. It had two large buildings: a chapel and a hall (with latrines) that served as a ward. The abbey area also had an almonry (a boarding school for poor boys), a water mill, a dovecote (for pigeons), and a fishpond.

Abbey's Properties

Churches Controlled by the Abbey

Churches in Leicestershire

- Asfordby, Leicestershire

- Barkby

- Barrow upon Soar

- Billesdon

- Bitteswell

- Blaby

- Cosby

- Croft

- Dishley

- Eastwell

- Enderby

- "Erdesby" (Arnesby?)

- Evington

- Harston

- Humberstone

- Hungarton

- Husbands Bosworth

- Illston on the Hill

- Kirkby Mallory

- Knaptoft

- Knipton

- Langton

- Leicester, All Saints' Church

- Leicester, St Leonard's Church

- Leicester, St Martin's Church

- Leicester, St Mary De Castro Church

- Leicester, St Michael's Church

- Leicester, St Nicholas' Church

- Leicester, St Peter's Church (Braunstone)

- Narborough

- North Kilworth

- Queniborough

- Shepshed

- Stoney Stanton

- Theddingworth

- Thornton

- Thorpe Arnold

- Thurnby

- Wanlip

- Westcotes

- Whetstone

Churches Outside Leicestershire

- Sharnbrook, Bedfordshire

- West Ilsley, Berkshire

- Adstock, Buckinghamshire

- Chesham, Buckinghamshire

- Youlgreave, Derbyshire

- Cockerham, Lancashire

- Great Billing, Northamptonshire

- Brackley, Northamptonshire

- Farthinghoe, Northamptonshire

- Eydon, Northamptonshire

- Syresham, Northamptonshire

- Stoke on Trent, Staffordshire

- Clifton-upon-Dunsmore, Warwickshire

- Curdworth, Warwickshire

- Bulkington, Warwickshire

Monastic Cells

- Cockerham Priory, Lancashire

Manors and Land Owned by the Abbey

Manors:

- Asfordby, Leicestershire

- Cawkesberia, Lancashire

- Cockerham, Lancashire

- Ingarsby, Leicestershire

- Kirkby Mallory, Leicestershire

- Knighton, Leicester

- Lockington, Leicestershire

Lands at:

- Anstey, Leicestershire

- Asfordby, Leicestershire

- Cossington, Leicestershire

- Pinslade, Leicestershire

- Ratby, Leicestershire

- Seagrave, Leicestershire

- Stoughton, Leicestershire

Leaders of the Abbey: A List of Abbots

| Abbot's Name | Election | End of Tenure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richard | 1143 or 1144 | 1168 (approx) | |

| William of Kalewyken | 1167 or 1168 | 1178 (approx) | |

| William of Broke | 1177 | 1186 | resigned |

| Paul | 1186 | 1205 | |

| William Pepyn | 1205 | 1222 or 1224 | |

| Osbert of Duntun | 1222 | 1229 | Died in office |

| Matthias Bray | 1229 | 1235 | Resigned; Likely due to pressure from Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln |

| Alan of Cestreham | 1235 | 1244 (?) | End of tenure estimated from the date of next abbot's election |

| Robert Furmentin | 1244 | 1247 (?) | End of tenure estimated from the date of next abbot's election |

| Henry of Rotheleye (Rothley) | 1247 | 1270 | Resigned |

| William of Shepheved (Shepshed) | 1270 | 1291 | Died in office |

| William of Malverne | 1291 | 1318 | Died in office |

| Richard of Tours | 1318 | 1345 | Died in office |

| William of Clowne | 1345 | 1378 | Died in office |

| William of Kereby | 1378 | 1393 | Died in office |

| Philip Repyngdon | 1393 | 1405 | Resigned to become "Chaplain and confessor" to King Henry IV. Repyngdon later became Bishop of Lincoln and a Cardinal. |

| Richard of Rothely | 1405 | 1420 | Resigned |

| William Sadyngton | 1420 | 1442 | Died in office after accusations of financial problems |

| John Pomery | 1442 | 1474 | Died in office |

| John Sepyshede | 1474 | 1485 | |

| Gilbert Manchestre | 1485 | 1496 | Died in office |

| John Penny | 1496 | 1509 | Resigned. |

| Richard Pescall | 1509 | December 1533 or January 1534 | Resigned after pressure from John Longland, Bishop of Lincoln and accusations of bad management. Received a pension of £100 a year. |

| John Bourchier | 1534 | 1538 | Was not a canon at the abbey before. Likely got the role through contacts with Thomas Cromwell. Gave up the abbey for dissolution in 1538, and received a large pension of £200 a year. Later considered for a Bishopric, then became rector of Church Langton. Left England around 1571 after refusing to accept Elizabeth I's new church laws. |

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |