London, Brighton and South Coast Railway facts for kids

|

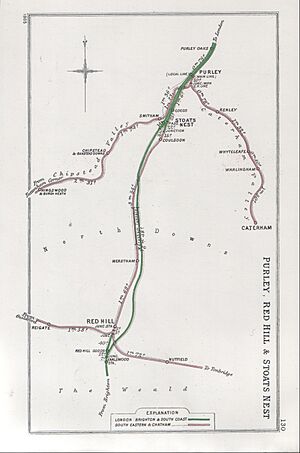

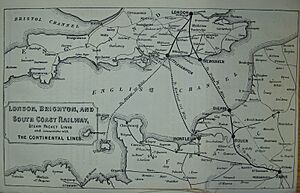

1920 map of the railway

|

|

The LB&SCR armorial device

|

|

| Technical | |

|---|---|

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

| Length | 457 miles 20 chains (735.9 km) (1919) |

| Track length | 1,264 miles 32 chains (2,034.9 km) (1919) |

The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR), also known as the Brighton Railway, was an important railway company in the United Kingdom. It operated from 1846 until 1922. Its railway lines covered a large area, forming a rough triangle with London at the top. The base of this triangle stretched along almost the entire coastline of Sussex, and it also covered a big part of Surrey.

The LB&SCR had direct routes from London to popular seaside towns like Brighton, Eastbourne, and Worthing. It also served important ports such as Newhaven. In London, it had a complex network of lines leading to major stations like London Bridge and Victoria.

The company was created in 1846 when five smaller railway companies merged. It later joined with other railway companies in southern England to form the Southern Railway on January 1, 1923.

Contents

- How the Company Started

- Growing the Railway: 1846–1859

- Fast Expansion: 1856–1866

- Financial Challenges and Recovery: 1867–1899

- The 20th Century: Improvements and War

- Train Services

- Electrification of Lines

- Accidents and Safety

- Trains and Carriages

- Ferry Services and Ships

- Buildings and Engineering

- The LB&SCR as an Investment

- Important People at the LB&SCR

- Working Conditions and Staff Relations

- Images for kids

How the Company Started

| London and Brighton Railway Act 1846 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act to consolidate and unite the London and Brighton and the London and Croydon Railway Companies and the Undertakings belonging to them. |

| Citation | 9 & 10 Vict. c. cclxxxii |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 27 July 1846 |

The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR) was officially formed by a special law passed by Parliament on July 27, 1846. This law brought together several railway companies:

- The London and Croydon Railway (L&CR), which started in 1836.

- The London and Brighton Railway (L&BR), which started in 1837.

- The Brighton and Chichester Railway.

- The Brighton, Lewes and Hastings Railway.

- The Croydon and Epsom Railway.

Most of these smaller companies were already owned by the L&BR or L&CR. The merger happened because shareholders were not happy with how their investments were doing.

The LB&SCR operated for 76 years. On December 31, 1922, it became part of the new Southern Railway, along with the London and South Western Railway and the South Eastern and Chatham Railway.

Original Railway Lines

When the LB&SCR was created, it had about 170 miles of railway lines already built or being built. These included three main routes and several smaller branches.

The main line to Brighton from London Bridge opened in 1841. Parts of this line were shared with the South Eastern Railway (SER). There were also new branch lines being built, like the one from Croydon to Epsom.

The West Sussex coast line started with a branch from Brighton to Shoreham in 1840. This line was extended to Chichester and later to Havant, with plans to reach Portsmouth.

The East Sussex coast line from Brighton to Lewes and St Leonards-on-Sea opened in 1846. It had branches to Newhaven and Eastbourne.

A short line from New Cross to Deptford Wharf was approved in 1846. It was only used for goods, not passengers, to avoid competing with the SER. A small branch from this line also opened to the Surrey Commercial Docks in 1855.

London Train Stations

The main London station for the LB&SCR was London Bridge. It was originally built by another company and the LB&SCR started using it in 1842. By 1849, the railway had its own tracks into London Bridge.

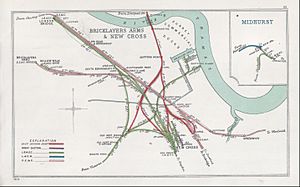

The LB&SCR also used a smaller SER station called Bricklayers Arms. This station was not good for passengers, so it closed in 1852 and became a goods station.

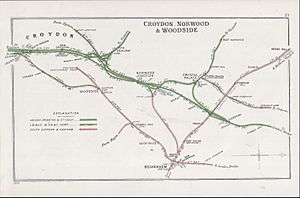

In Croydon, the LB&SCR owned three stations: East Croydon, Central Croydon, and West Croydon.

Atmospheric Trains

The L&CR had tried to use a special "atmospheric" system for some of its trains. This system used air pressure in a tube to move trains. However, it had many problems, and the LB&SCR stopped using it in 1847. This allowed the company to build its own lines into London Bridge.

Growing the Railway: 1846–1859

The LB&SCR was formed during a time when it was hard to get money for new railway projects. Despite this, the company managed to complete projects that were already started.

The LB&SCR had some disagreements with the SER, especially where they shared tracks and stations. In 1849, a new chairman, Samuel Laing, helped make an agreement with the SER. This agreement helped define which areas each railway would serve.

In 1847, the LB&SCR started services to Portsmouth, sharing a line with the London and South Western Railway (L&SWR). Later, a more direct line to Portsmouth was planned. This led to a famous disagreement in 1858 called the "battle of Havant," where the LB&SCR tried to stop the L&SWR from using its tracks. The issue was settled in court in 1859.

Samuel Laing also approved some smaller expansions, like a branch line from Three Bridges to East Grinstead in 1855.

Crystal Palace Branch Line

Some of the LB&SCR directors were involved in moving The Crystal Palace to Sydenham Hill after the Great Exhibition in 1851. The Crystal Palace became a huge tourist attraction. The LB&SCR built a branch line to it, which opened in 1854. This line was very successful, bringing thousands of passengers every day.

Fast Expansion: 1856–1866

After Samuel Laing retired in 1855, Leo Schuster became chairman. He started a plan to quickly expand the railway network across south London, Sussex, and east Surrey. Many new lines were built or planned during this time.

Connecting to West London

Schuster supported a company called the West End of London and Crystal Palace Railway (WEL&CPR). This company built a new line from the Crystal Palace branch to Battersea by 1858. The LB&SCR then leased this line and made it part of its system.

| Croydon and Balham Hill Railway Act 1860 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act to authorize the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway Company to make a Railway from the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway in the Parish of Croydon to the West End of London and Crystal Palace Railway near Balham Hill, all in the County of Surrey, with a Branch Railway connected therewith; and for other Purposes. |

| Citation | 23 & 24 Vict. c. cix |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 3 July 1860 |

The LB&SCR also became a major shareholder in the Victoria Station and Pimlico Railway (VS&PR). This company built the Grosvenor Bridge over the River Thames and the line to Victoria Station. This created a route from Croydon to the West End of London. A new shortcut line was built between Norwood and Balham in 1861-1862, making the journey to Victoria even shorter.

New Lines in South London

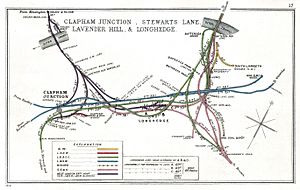

The VS&PR line also connected to the West London Extension Joint Railway. This line was shared by several railway companies and opened in 1863. In the same year, the LB&SCR and L&SWR jointly opened a large station called Clapham Junction.

The LB&SCR also worked with the London Chatham and Dover Railway (LC&DR) to create the South London line. This line connected London Bridge and Victoria, passing through areas like Denmark Hill and Peckham.

New Lines in Sussex

| London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (Additional Powers) Act 1864 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act to enable the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway Company to make new Lines of Railway in the Counties of Surrey and Sussex; to acquire additional Lands; and to acquire the Undertakings of certain other Companies; and for other Purposes. |

| Citation | 27 & 28 Vict. c. cccxiv |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 29 July 1864 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

In 1858, a branch line was built from Lewes to Uckfield. This was later extended to Groombridge and Tunbridge Wells. The Newhaven branch was extended to Seaford in 1864. The East Grinstead line was also extended to Groombridge and Tunbridge Wells in 1866.

The LB&SCR wanted to connect Eastbourne and Tunbridge Wells. In 1864, it got permission to build a line between these towns. It also planned the Ouse Valley Railway, but this project was not completed.

In West Sussex, the Horsham branch was extended to Pulborough and Petworth in 1859. A new line from Horsham to Shoreham opened in 1861, providing a direct link to Brighton. Branches were also built to Littlehampton (1863), Bognor Regis (1864), and Hayling Island (1867).

A line from Pulborough to Ford opened in 1863. This gave the LB&SCR a shorter route from London to Portsmouth.

New Lines in Surrey

The LB&SCR shared a line from Wimbledon through Epsom to Leatherhead with the L&SWR. The LB&SCR then bought the Banstead and Epsom Downs Railway, which built a branch line from Sutton to Epsom Downs for the Epsom Downs Racecourse. This opened in 1865.

The LB&SCR also built lines connecting Horsham to towns in Surrey. A line from West Horsham to Guildford opened in 1865. A line from Leatherhead to Dorking opened in 1867, and was extended to Horsham two months later. These lines created more routes from London to Brighton and the West Sussex coast.

Newhaven Harbour

After the line to Newhaven opened, the LB&SCR wanted to create a shorter route from London to Paris via Dieppe. This would compete with other routes. The LB&SCR built wharves and warehouses at Newhaven and helped dredge the channel to allow larger ferries. In 1863, the LB&SCR and a French railway company started a passenger service between Newhaven and Dieppe.

Growth of London Suburbs

The railway helped the area between New Cross and Croydon grow rapidly. The population of Croydon increased greatly during the LB&SCR's time. In the 1860s, the LB&SCR started to get more passengers from middle-class people living in the south London suburbs and working in central London.

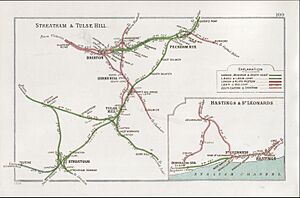

As part of this growth, the LB&SCR built a line from Peckham Rye through East Dulwich, Tulse Hill, Streatham, and Mitcham to Sutton and Epsom Downs. This line opened in October 1868.

Troubled Relations with the SER

The relationship between the LB&SCR and the SER remained difficult. They often disagreed about shared lines and agreements. One big problem was the shared line between East Croydon railway station and Redhill. This line was very busy, and the SER's trains often caused delays for LB&SCR trains.

Eventually, an independent expert was brought in to help resolve the issues in 1889. The expert supported the LB&SCR's right to use the line but increased the annual payment it had to make.

Financial Challenges and Recovery: 1867–1899

A financial crisis in 1866-1867 almost caused the LB&SCR to go bankrupt. A report showed that the company had spent too much money on large projects. Many country lines were losing money. The report criticized the company's leaders, who then resigned.

The new leaders, including Samuel Laing who returned as chairman, helped the company recover. They stopped many new construction projects, including the Ouse Valley Railway. For the next ten years, new projects were limited to small improvements or joint ventures with other companies.

One important project the LB&SCR was involved in was the East London Railway. This railway reused the Thames Tunnel and connected the LB&SCR at New Cross to other railways. It was mainly for goods, but the LB&SCR also ran a passenger service.

Later 19th Century Growth

| London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway (Various Powers) Act 1878 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act to confer further powers upon the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway Company, and to enable them to purchase the Hayling Bridge and Causeway. |

| Citation | 41 & 42 Vict. c. lxxiv |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 17 June 1878 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

By the mid-1870s, the LB&SCR was financially stable again. It focused on using its lines more efficiently and reducing costs. The company's income grew significantly. The main reason for this recovery was the growth of London suburban traffic. By the late 1880s, the LB&SCR had the largest suburban network of any British railway.

New Routes and Station Upgrades

| London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway (Croydon, Oxted, and East Grinstead Railways) Act 1878 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act to enable the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway Company to complete and construct Railways between Croydon, Oxted, and East Grinstead, and to acquire the Lewes and East Grinstead Railway; to confer powers on the South-eastern Railway Company; and for other purposes. |

| Citation | 41 & 42 Vict. c. lxxii |

The plan to link Eastbourne with Tunbridge Wells was restarted in 1879. This line, later known as the Cuckoo Line, was completed in September 1879.

In 1877, a new railway called the Lewes and East Grinstead Railway was approved. The LB&SCR later acquired and operated these lines, which opened in 1882 and 1883. This line became known as the "Bluebell line."

In West Sussex, a link between Midhurst and Chichester opened in 1881. The LB&SCR also leased the Hayling Island branch line from 1874.

The LB&SCR and SER worked together on a joint line between South Croydon and Oxted. This line opened in 1884.

Brighton railway station was rebuilt and expanded in 1882-1883. Eastbourne station was also rebuilt in 1886 to handle more passengers.

Solving Congestion and Slow Trains

As traffic grew in the South London suburbs, the LB&SCR faced criticism for slow trains and delays. This was partly due to the complex network of lines and signals, and the shared tracks with the SER.

To solve this, the LB&SCR decided to build its own line between Coulsdon North and Earlswood, bypassing Redhill. This new line was called the "Quarry line." It involved building new tunnels and cuttings. The Quarry line opened for passengers on April 1, 1900.

The 20th Century: Improvements and War

In its last 20 years, the LB&SCR did not open many new lines. Instead, it focused on improving its main line and London stations. It also started electrifying its London suburban services.

After the Quarry line was finished, the main line to Brighton still had busy sections further south. The company planned to add more tracks along the entire line, but only 16 miles were completed between 1906 and 1909. The money was then used for electrification.

The LB&SCR had to share its London stations, London Bridge and Victoria, with other railway companies. As more people started commuting, there was an urgent need to expand Victoria station. Between 1898 and 1908, the line to Victoria was widened, and the station was rebuilt to be much larger. London Bridge station was also expanded.

Locomotive Shortage

Between 1905 and 1912, the LB&SCR had a serious shortage of locomotives. Its workshops in Brighton could not keep up with repairs and building new engines. This problem was solved by building new carriage works at Lancing and reorganizing the Brighton workshops.

The First World War (1914-1918)

During the First World War, the British government took control of all railways, including the LB&SCR. The railway's role changed dramatically. It became responsible for carrying most of the supplies and ammunition to British troops in Europe, mainly through its port at Newhaven. This included nearly 7 million tons of goods, with 2.7 million tons of explosives. This required over 53,000 extra goods trains during the war.

Newhaven harbour also received wounded soldiers on hospital ships, and the railway provided ambulance trains. Many army camps were in the LB&SCR's area, so it ran over 27,000 troop trains.

To handle this extra traffic, the railway made big improvements to its infrastructure. Newhaven harbour got more warehouses, sidings, and electric lighting. A large goods sorting yard was built at Three Bridges. Passing loops were added at Gatwick and Haywards Heath to prevent passenger trains from being delayed by slower goods trains.

Many LB&SCR staff joined the armed forces, leading to staff shortages. Women were hired for clerical jobs and cleaning carriages. In 1920, the railway put up a War Memorial at London Bridge to honor the 532 staff who died.

The End of the LB&SCR

By December 31, 1922, when the LB&SCR stopped being an independent company, it had 457 miles of railway lines. The company was known for being unique in its strengths and weaknesses.

Train Services

The LB&SCR mainly carried passengers, with goods traffic being a smaller part of its business. At first, the railway was mostly for long-distance travel between London, Croydon, and the south coast. However, the railway's presence helped towns and villages along its lines grow. After 1870, the growth of London's southern suburbs greatly changed the railway's services. The development of Newhaven harbour also boosted both passenger and goods traffic.

In the 1890s, the LB&SCR was criticized for slow and unpunctual trains. This was partly due to the complex system in London and the shared lines with the SER. The company gradually improved its reputation in the 20th century by upgrading its main lines and electrifying suburban services.

Express Passenger Services

The company did not have very long-distance express trains, with journeys usually no more than 75 miles. However, it ran frequent express services to important coastal towns from both London Bridge and Victoria. Income from season tickets, especially for travel between Brighton and London, was very important to the LB&SCR's finances.

The LB&SCR was one of the first railways in England to use special Pullman cars in 1875. It also pioneered all-Pullman trains in England with the Pullman Limited Express in 1881. These were the first electrically lit coaches on a British railway.

The Brighton Limited train was introduced in 1898. It ran only on Sundays and was advertised to make the journey from Victoria to Brighton in 60 minutes. In 1902, it made a record run in 54 minutes. The Southern Belle, introduced in 1908, was called "the most luxurious train in the World."

Stopping Trains

Slower passenger trains between London and the south coast often split at East Croydon. This allowed them to serve both London stations (London Bridge and Victoria). East Croydon was a very important hub for these trains.

Slip Coaches

The LB&SCR seems to have invented the idea of "slipping" coaches from the back of express trains at stations. This allowed coaches to be dropped off for branch lines or smaller stations without the whole train stopping. The earliest example was in 1858 at Haywards Heath. This practice continued until the main line was electrified in 1932.

London Suburban Traffic

After 1870, the LB&SCR greatly encouraged commuters by lowering the price of season tickets. It also introduced special "workmen's trains" for manual workers in 1883. By 1890, the company ran more trains into its London stations each month than any other company. This growth changed the railway and led to new types of locomotives and services. When steam trains could no longer handle the increased traffic, the London suburban network was electrified.

Holiday and Excursion Trains

The LB&SCR offered special "excursion trains" from London to the South Coast and the Sussex countryside since 1844. Special fares for summer Sundays and holidays were often advertised. The company also ran special trains for events at Crystal Palace.

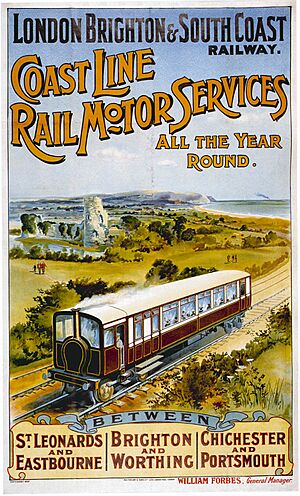

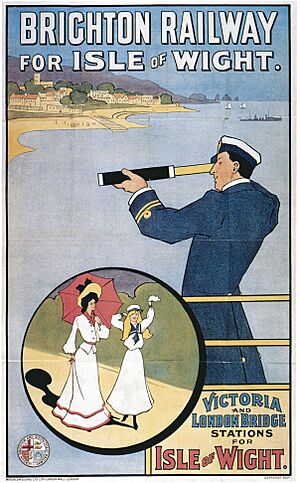

After 1870, the LB&SCR worked to develop holiday travel. It promoted other south coast resorts like Hayling Island and the Isle of Wight as holiday spots, using attractive posters. In the 1900s, it ran special Sunday trains for London cyclists to explore the countryside. By 1905, the railway offered day trips to Dieppe in France.

The LB&SCR served important horse racing tracks, and special race day trains were a big source of income during the summer.

Rail Motor Services

In the early 1900s, the LB&SCR looked into using steam or petrol "railcars" for short-distance services that were losing money. These railcars were compared to small steam locomotives that could be used in "motor train" or "push-pull" setups. The railcars were not very successful, but the "motor trains" worked well because extra coaches could be added or removed. This gave a new life to older steam locomotives, which continued to be used on branch lines.

Freight Services

Freight was a smaller part of the LB&SCR's business for its first 50 years. It carried farm goods, general merchandise, and imported items from France. In the 1890s, freight traffic grew rapidly due to new industries like petroleum, cement, and brick making.

The main London goods depot was at "Willow Walk," part of the Bricklayers Arms complex. There were also freight facilities at Battersea and Deptford Wharves. A large sorting yard was built south of Norwood Junction in the 1870s.

Electrification of Lines

In 1900, proposals for an "Electric Railway" from London to Brighton failed, but they made the LB&SCR consider using electricity for its trains. Also, competition from new trams in London caused passenger numbers to drop on the route between Victoria and London Bridge.

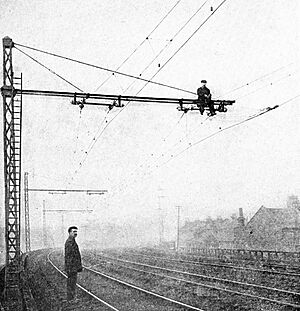

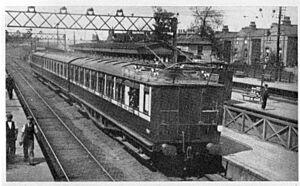

Because the LB&SCR had many commuters traveling short distances, it was a good candidate for electrification. The company decided to use a high-voltage overhead power system (6,600 volts AC). This system was from Germany.

The first electric section was the South London line, connecting London Bridge with Victoria. It opened on December 1, 1909. It was called "The Elevated Electric" and was an instant success. Passenger numbers on the line jumped from 3 million to 10 million journeys per year. Other routes followed, including Victoria to Crystal Palace in 1911.

The success of these early electric lines led the LB&SCR to plan to electrify all its remaining London suburban lines in 1913. However, the outbreak of the First World War delayed these plans. By 1921, most of the inner London suburban lines were electrified.

The "Elevated Electric" was a technical and financial success. However, it was short-lived. The London and South Western Railway used a different system (third-rail). In 1926, the Southern Railway announced that all overhead lines would be converted to the third-rail system. The last overhead electric train ran on September 22, 1929.

Accidents and Safety

The LB&SCR used semaphore signals and signal boxes from its early days. In its first few years, there were some serious accidents, often due to communication problems. The company started to improve safety in the 1860s by introducing "interlocking" (a system that prevents signals and points from being set incorrectly) and early air brakes. Given how busy its railway system was, the LB&SCR had a good safety record in its later years.

Here are some notable accidents that happened on the LB&SCR:

- On June 6, 1851, a train derailed at Falmer Bank because of an object on the line.

- On November 27, 1851, a passenger train crashed into a goods train near Ford because the passenger train went past a red signal.

- On August 21, 1854, an accident at East Croydon killed three people and injured eleven.

- On August 25, 1861, in the Clayton Tunnel rail crash, one train crashed into the back of another inside Clayton Tunnel. This was the deadliest accident in the UK at the time, killing 23 people and injuring 176.

- On May 29, 1863, a train derailed at Streatham Common, killing four people and injuring 59.

- On May 1, 1891, a cast-iron bridge collapsed under a train at Norwood Junction, injuring six people.

- On December 23, 1899, a train crashed into the back of another in thick fog at Keymer Junction, killing six people and injuring 20.

- On January 29, 1910, an express passenger train derailed at Stoat's Nest due to a faulty wheel. Seven people were killed and 65 were injured.

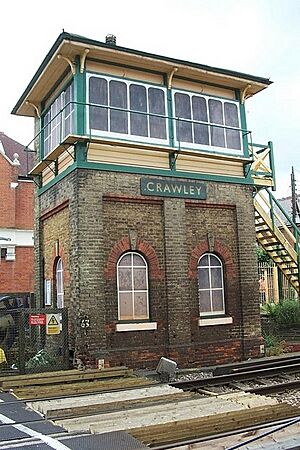

Signalling and Signal Boxes

The LB&SCR used different types of signals. In 1856, John Saxby, an LB&SCR carpenter, invented a way to manually "interlock" points and signals. This system was first tried at Bricklayers Arms. Saxby later left the company and started his own signalling company, Saxby & Farmer.

The LB&SCR inherited the world's first signal boxes. After 1880, it started to develop its own designs for signal boxes. When Victoria Station was rebuilt between 1898 and 1908, it was resignalled using an advanced electromechanical system.

Trains and Carriages

For most of its history, the LB&SCR used steam locomotives to pull its trains. It did not own diesel or electric locomotives. The electrified lines used electric multiple units for passengers, while steam trains still handled freight. The company experimented with petrol railcars, but they were not successful.

The LB&SCR was one of the first railways in Britain to use the Westinghouse air brake after 1877. This was much more effective than other braking systems used by other railways.

Steam Locomotives

The LB&SCR inherited 51 steam locomotives and built or bought 1,055 more. Of these, 620 were passed on to the Southern Railway in 1923.

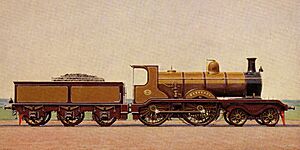

The LB&SCR became famous for using the Jenny Lind locomotive in 1847. This design was later used by many other railways. John Chester Craven, the Locomotive Superintendent from 1847 to 1869, designed many different types of locomotives. While many were good, having 72 different classes was not efficient.

William Stroudley, who took over in 1870, reduced the number of main classes to 12. He designed very successful and long-lasting locomotives, such as the A1 ('Terrier') and D1 classes. His locomotives were known for being limited to six wheels, partly because of the size of the turntables at stations like Victoria.

Stroudley's successor, R. J. Billinton, continued to standardize locomotive parts, which helped reduce maintenance costs. He introduced eight-wheeled designs for express trains and London suburban services.

D.E. Marsh continued building larger locomotives. He also designed the I3 class of locomotives, which were very successful and showed the benefits of "superheating" (making steam hotter for more power).

The last Chief Mechanical Engineer was L.B. Billinton. He designed powerful locomotives like the K class and L class. These designs were successful, but his career was cut short by the First World War and the grouping of railways.

LB&SCR locomotive designs did not have a big impact on the Southern Railway after 1923. This was because they were built to a different size and used Westinghouse air brakes, unlike the other main companies. However, the original LB&SCR locomotives proved to be very long-lasting.

Electric Trains

The electrified lines used electric multiple units. These were originally three-car units, later changed to two-car units. New types of units were developed for each electrified line.

Passenger Carriages

The LB&SCR was not always at the forefront of carriage design. In the mid-1860s, it was still building open-sided third-class carriages. Stroudley introduced four-wheeled and later six-wheeled designs that lasted for 40 years. He also pioneered electric lighting and communication cords on trains. The LB&SCR was one of the first to offer breakfast cars on its main business trains.

Later, in the early 1900s, better carriages appeared, including "Balloon stock" and electric stock. Sixteen LB&SCR carriages have been preserved today, including a luxurious "Directors' saloon."

Wagons

Sixteen wagons that belonged to the LB&SCR still exist today. Many of these were transferred to the Isle of Wight by the Southern Railway and remained in use until the 1960s.

Train Colours (Liveries)

After 1870, the LB&SCR was known for its attractive locomotives and carriages.

Before 1870, passenger locomotives were painted a dark green with red frames. Goods locomotives were black. Some engines had polished wooden strips on their boilers.

From 1870 to 1905, the livery was Stroudley's famous Improved Engine Green, a golden yellow colour. Passenger locomotives had olive green borders with black, red, and white lines. Frames and buffer beams were red. Goods engines were all olive green. This livery was very decorative and is still remembered today. Carriages were mahogany in colour.

From 1905 to 1923, express locomotives were a dark brown colour. Secondary passenger locomotives used a similar colour but with yellow paint instead of gold. Goods engines were shiny black. Carriages were initially olive green, then changed to plain brown.

Ferry Services and Ships

The LB&SCR invested in ferry services across the English Channel. After the line to Newhaven opened in 1847, the company improved Newhaven harbour. A ferry service between Newhaven and Dieppe was established in 1847, and later reinstated in 1853.

In 1862, the LB&SCR gained the power to own and operate its own ships. In 1863, the LB&SCR and a French railway company agreed to jointly operate the Newhaven–Dieppe passenger service. This was advertised as the "shortest and cheapest" route to Paris.

The LB&SCR also operated ferry services from Littlehampton to Honfleur. By 1880, railway lines connected the Ryde Pier and Portsmouth Harbour ferry terminals. The LB&SCR and the L&SWR formed a joint company to buy the ferry operators.

In 1884, a company started a goods rail ferry between Langstone and St Helens on the Isle of Wight. This ferry, called Carrier, was designed to carry railway trucks. The project was not successful, and despite being acquired by the LB&SCR in 1886, it ended in 1888.

The LB&SCR operated many ships on its own, jointly with the French railway company, and as part of the joint ferry service.

Buildings and Engineering

The LB&SCR inherited or built many important structures, including:

- Bridges and viaducts: like the impressive Ouse Valley Viaduct.

- The Norwood Junction flyover, which was the world's first railway overpass.

- Tunnels: such as Merstham and Clayton.

- Stations: including modular station buildings designed by David Mocatta.

Stations

The LB&SCR had 20 main stations, including major ones at London Bridge, Victoria, and Brighton. Important junction stations included Clapham Junction and East Croydon.

Later, during the 1880s, the LB&SCR built many country stations with elaborate, decorated designs, especially on the Bluebell and Cuckoo Lines.

Workshops and Depots

The L&BR set up a repair workshop at Brighton in 1840. Over 1,200 steam locomotives were built there before it closed in 1962. There were also smaller repair facilities in London.

By the early 1900s, the Brighton works could not handle all the repairs and new construction needed. So, in 1911, the LB&SCR built a new carriage and wagon works at Lancing. A marine engineering workshop was also set up at Newhaven in the 1870s.

The company had engine sheds (where locomotives were stored and maintained) at many locations, including Brighton, New Cross, and Three Bridges.

The main offices of the LB&SCR were at Brighton railway station until 1892, when they moved to the former Terminus Hotel at London Bridge.

Hotels

The LB&SCR opened the Terminus Hotel at London Bridge and the Grosvenor Hotel at Victoria in 1861. The London Bridge hotel was not successful and became offices for the railway. The Grosvenor Hotel was rebuilt and expanded in 1901. The LB&SCR also owned the Terminus Hotel next to Brighton station and operated the London and Paris Hotel at Newhaven.

The LB&SCR as an Investment

After the financial crisis of 1867, a report found that the company had not managed its money well. However, by 1890, an economist named William Ramage Lawson studied the LB&SCR's finances. He concluded that investing in the LB&SCR was a good idea because it offered high returns and had good future prospects.

He gave several reasons for this, including:

- A well-established route with little competition.

- Many different sources of traffic (passengers and goods).

- Reasonable operating costs due to good construction and maintenance.

- Energetic and careful management.

From 1870 onwards, the LB&SCR was generally a well-run and profitable railway for its shareholders.

Important People at the LB&SCR

Here are some of the key people who led and managed the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway:

Chairmen of the Board of Directors

- Samuel Laing (served twice, 1848–1855 and 1867–1896)

- Leo Schuster (1856–1866)

- Earl of Bessborough (1908–1920)

General Managers

- John Peake Knight (1870–1886)

- Sir Allen Sarle (1886–1897)

- William de Guise Forbes (1899–1922)

Chief Engineers

- Robert Jacomb-Hood (1846–1860)

- Frederick Banister (1860–1895)

- Charles Langbridge Morgan (1895–1917)

Locomotive Superintendents

- John Chester Craven (1847–1870)

- William Stroudley (1870–1889)

- R. J. Billinton (1890–1904)

- D. E. Marsh (1905–1911)

- L. B. Billinton (1912–1922)

Other Notable People

- Curly Lawrence, a famous model steam locomotive designer, worked as a fireman on the LB&SCR when he was young. He even took the railway's initials (LBSC) as his nickname.

Working Conditions and Staff Relations

| London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (Pensions) Act 1899 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act to provide for the establishment and regulation of a Pension Fund for officers and servants of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway Company. |

| Citation | 62 & 63 Vict. c. liv |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 13 July 1899 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

For its time, the LB&SCR was considered a good employer. In 1851, it set up a fund to help staff who became unable to work. From 1854, it also ran a savings bank for its employees.

In 1867, there was a two-day strike by drivers and firemen over their working hours, which was resolved through talks. In 1872, a retirement fund was created for higher-ranking staff. This was expanded to a pension fund for all staff in 1899, thanks to a special law.

However, relations between railway management and staff, especially locomotive crews and workshop staff, became difficult between 1905 and 1910. This led to some strikes and dismissals. The situation improved under the next Locomotive Superintendent.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |